There are 11 minutes of action in the average National Football League (NFL) game, according to a 2010 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) stopwatch study conducted by Stuart Silverstein. Silverstein started the stopwatch at the snap of the ball and stopped it at the tackle of the ball carrier. I know what you’re thinking, “11 minutes? C’mon! I know all about the delays inherent in the modern game, but 11 minutes? You’re going to have to back that up.”

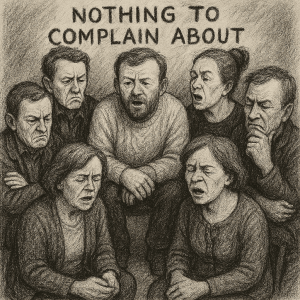

I don’t keep a ledger on the complaints I’ve had about delays in the NFL game throughout the course of my life, but my family would probably characterize that number with a sigh or a groan. Even in the most frustrating moments, I never thought about how few moments of action actually occur in an average 3 hour and 12 minute NFL telecast. If you’re approaching this from a static level, based on the number of complaints you’ve listed over the years, you might say, “11 minutes seems about right” in the most cynical tone possible. Now, remove yourself from your “Nothing shocks me” mindset and view this in a more objective frame. If the average NFL game lasts 3 hours and 12 minutes, and 3 hours and 12 minutes equals 192 minutes, we spend 181 minutes waiting for something to happen in every NFL game we watch. No matter how we spin it, that’s a lot of sitting on furniture, staring at the TV blankly, and waiting for the snap of the ball. The only thing I can come up with is that we spend so much time thinking about what could or should happen that we don’t really notice how long it took to happen, or should I say we do and we don’t.

Those who are not stunned by that 11 minute figure, are likely casual fans who enjoy going to other peoples’ houses for a gathering, the party, or the event status that football games have become in our lives. They’re people who enjoy all of the talking that happens between moments of action more than the game. If we drill down to the nuts and bolts of their fandom, they’d probably admit they like the team, but they don’t like like them. They enjoy watching them win, because it’s always fun to be part of a communal celebration, but they’re not devastated when the team loses. They say things like, “Well, at least it was a good game,” as if this were a television drama that didn’t end well but was nonetheless entertaining. They’re probably the type who leave their friend’s house laughing, they drive home, put the kids to bed, and kiss the wife, and slip into bed without ever thinking about that game again. They have such a healthy relationship between football and life that they can enjoy football game gatherings for what they are, and they spend most of those 181 minutes of inaction chatting it up, eating, drinking, and having a merry, old time. The NFL game is background noise for them, and they check in on the score every once in a while.

Those who are not stunned by that 11 minute figure, are likely casual fans who enjoy going to other peoples’ houses for a gathering, the party, or the event status that football games have become in our lives. They’re people who enjoy all of the talking that happens between moments of action more than the game. If we drill down to the nuts and bolts of their fandom, they’d probably admit they like the team, but they don’t like like them. They enjoy watching them win, because it’s always fun to be part of a communal celebration, but they’re not devastated when the team loses. They say things like, “Well, at least it was a good game,” as if this were a television drama that didn’t end well but was nonetheless entertaining. They’re probably the type who leave their friend’s house laughing, they drive home, put the kids to bed, and kiss the wife, and slip into bed without ever thinking about that game again. They have such a healthy relationship between football and life that they can enjoy football game gatherings for what they are, and they spend most of those 181 minutes of inaction chatting it up, eating, drinking, and having a merry, old time. The NFL game is background noise for them, and they check in on the score every once in a while.

“What’s the score?” my dad would ask, stepping into the living room. We’d tell him, and he’d go back to doing whatever he was doing. That used to drive us nuts. He didn’t care about the game, the logistics, the nuances, or any of the smaller moments that defined winning or losing. He just wanted to know the score. As much as he claimed to like football, it was a passing interest to him. As I grew older I realized he was more emblematic of the average, casual NFL fan than I was. I also realized his relationship to football was far more healthy than mine.

Similar to my dad, most average, casual fans don’t understand why any team, college or pro, doesn’t throw a bomb on every play. When Notre Dame had Raghib Ismail “The Rocket,” on their team, my dad didn’t understand why The Irish didn’t just throw the ball to him every time. As myopic as that sounds, it’s a good question that just about every casual fan asks when they see an athlete who appears so superior to the other athletes on the field that it appears that he can do whatever he wants on the field.

Author Chuck Klosterman answers this decades-old question in his book Football, by quoting a track and field coach who, when asked why track and field isn’t more popular in America, said, “Track has a problem. The fastest guy always wins.” After 2007, Usain Bolt won approximately 95% of the individual 100m/200m finals in the Olympics and World Championship races he ran in between 2008 and 2016. There are variables such as reaction time, start technique, lane conditions, etc., that can lead to an upset, but there are no strategies Bolt’s opponents can legally employ to slow him down. There are no counter-veiling forces in track, no defense, so the fastest guy almost always wins.

“I get that they need to keep the defense guessing with the occasional run, but why do they always run right up the middle?” Julie Ann asked Andrew. “That’s where most of the defenders are. Why don’t they run around the side?”

“To further fool the defense,” Andrew, the football enthusiast, explains. “A run up the middle better sets up the play-action fake and pulls the linebackers forward a step or two to open up the middle of the field.”

“To further fool the defense,” Andrew, the football enthusiast, explains. “A run up the middle better sets up the play-action fake and pulls the linebackers forward a step or two to open up the middle of the field.”

“So, it’s a wasted play?” she asks. “It’s a play to set up another play? Boring!”

“It’s strategic,” Andrew admits. “If they gain 6-7 yards on that first down run play it opens up a number of possibilities for the next play, but if all a team does is go for the big plays, the defense will adjust, and they’ll execute their plan to stop the big plays. Defenses employ numerous methods to compensate for exceptional athleticism, so an offensive coordinator has to put in some “boring”plays, as you call them, to mess with the defensive coordinator’s mind.”

A run up the middle is widely viewed by casual fans, like Julie Ann, as the little plays of the game, or “The boring part.” Andrew, the enthusiast, knows a little more about the chess match between coordinators, but he’ll likely never be able to explain that intricacies of the game, as he understands them — on a level just a couple notches above rudimentary– to a casual fan like Julie Ann. If Andrew cannot explain the intricacies of football on a conversational level, it might expose the fact that he doesn’t know what he doesn’t know, or if he can, Julie will likely dismiss his long, intricate explanation with an, “Uh huh, BORING!”

If Julie Ann is a decent example of the average, casual NFL fan, she doesn’t pay attention to an overwhelming amount of the 65-70 plays in the average NFL game. She’ll probably talk through an overwhelming number of those plays. Yet, Julie Ann is a fan, and she does enjoy watching these games, but her attention drifts until the high-leverage plays that add to her team’s Win Probability with crucial, clutch, and dagger-inducing plays. Analysts suggest that there are typically 5-10 game-changing plays per game. Andrew might suggest that is far too high, and that most NFL games are decided, or swung, on 3-4 plays at most. For the sake of consistency, we’ll stick with the analysts findings, and we’ll go with the median and say that there are an average of 7.5 noteworthy “Pay attention” plays per game that are instrumental in wins and losses. If each play last an average of four seconds, then Julie Ann, the casual fan, will want to pay attention to approximately 30 seconds of each 3 hour and 12 minute NFL game, if she wants to sound like an informed fan.

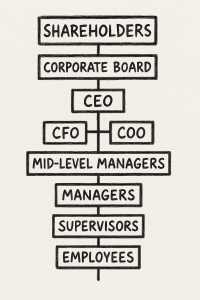

As popular as the NFL is, surveys find that 26% to 46% characterize themselves as casual fans, and NFL enthusiasts, or avid fans, defined through daily engagement of some sort, list at approximately 21% to 36%. If these numbers hold in their workplace, when Julie Ann and Andrew return to work the next day to describe the game for all of their co-workers who missed the game, they’ll probably sound equally informed, even though Julie Ann only paid attention to the most crucial 30 seconds of that game, and Andrew, the avid enthusiast, focused intently on the 11 minutes of action.

“You guys don’t understand the game,” Andrew might say to those who think Julie Ann offered a wrap-up as complete as his, and he might be right, but his audience either won’t notice the difference, or they won’t care. The latter is illustrated by the coverage the average sports’ network, newspaper, internet page, and/or sports radio attributes to that game. There are exceptions, of course, there are always exceptions, but most of their coverage will focus on the 30 most crucial seconds of the game Julie Ann discussed. In my experience 30 seconds might even a bit of an exaggeration, as most post-game television broadcasts limit their highlight packages to about half of those 30 seconds, and fill the rest with graphics and analysis of those 15 seconds. Julie Ann didn’t watch the game as intently as Andrew, and she doesn’t care to know how the “BORING!” plays influence and pave the way for the exciting ones, but she remembers the exciting plays, and she might even watch some of the thousands of hours devoted to those 15 seconds, and she reads expert analysis on the hundreds of articles on the internet, until she sits next Andrew at a family gathering and sounds just as knowledgeable as the more enthusiastic fan who knows how various intangibles can affect an outcome.

“You guys don’t understand the game,” Andrew might say to those who think Julie Ann offered a wrap-up as complete as his, and he might be right, but his audience either won’t notice the difference, or they won’t care. The latter is illustrated by the coverage the average sports’ network, newspaper, internet page, and/or sports radio attributes to that game. There are exceptions, of course, there are always exceptions, but most of their coverage will focus on the 30 most crucial seconds of the game Julie Ann discussed. In my experience 30 seconds might even a bit of an exaggeration, as most post-game television broadcasts limit their highlight packages to about half of those 30 seconds, and fill the rest with graphics and analysis of those 15 seconds. Julie Ann didn’t watch the game as intently as Andrew, and she doesn’t care to know how the “BORING!” plays influence and pave the way for the exciting ones, but she remembers the exciting plays, and she might even watch some of the thousands of hours devoted to those 15 seconds, and she reads expert analysis on the hundreds of articles on the internet, until she sits next Andrew at a family gathering and sounds just as knowledgeable as the more enthusiastic fan who knows how various intangibles can affect an outcome.

Andrew’s love of the NFL game is pure and sincere, so on one level he doesn’t care what anyone thinks, but on another level, we all want some recognition for the accumulated knowledge of anything we’ve acquired. Yet, Andrew will consider it unfair that everyone considers Julie Ann just as knowledgeable football as he is, until he eventually runs into a fanatic who is as enthusiastic about football as he is. This conversation might start great, as we all love meeting someone who can appreciate the game on our level, but that appreciation will eventually go one of three ways. The best possible outcome for the future friendship between Andrew and his fellow fanatic will play out if their girlfriends stop their conversation with a “No football conversations.” At that point, all four will laugh and Andrew and the fanatic will secretly harbor mutual respect for one another, but if they are allowed to explore the topic with one another, it will either turn into a duel of knowledge with no winners, or both will walk away from the conversation characterizing the other as an NFL nerd without recognizing that the other sounds exactly like them to disinterested parties.

Football vs. Baseball

The WSJ did not conduct a similar stopwatch study on basketball and hockey, since it is generally accepted that the games in the National Basketball Association (NBA) have 48 minutes of action in an average 2.5 hour game, and the National Hockey League (NHL) match has 60 minutes of action in an average 2.5 hour game. Save for various breaks, the ball/puck is almost always in motion in those sports, so conducting a stopwatch study would be relatively obvious. The WSJ did conduct a similar study on the average Major League Baseball (MLB) game, however, and they found that the average baseball game has 17 minutes and 58 seconds of action in a game that is now an average of 2 hours and 36 minutes long. Punching these numbers into the system, football has an action-to-total-time ratio of approximately 5.7%, and baseball has an action-to-total-time ratio of approximately 11.5%. So, to those who find baseball games in the MLB boring, they actually have a greater, slightly more than double, action ratio than the NFL. We could debate the definition of action, in qualitative vs. quantitative terms, but the numbers don’t lie.

The WSJ did not conduct a similar stopwatch study on basketball and hockey, since it is generally accepted that the games in the National Basketball Association (NBA) have 48 minutes of action in an average 2.5 hour game, and the National Hockey League (NHL) match has 60 minutes of action in an average 2.5 hour game. Save for various breaks, the ball/puck is almost always in motion in those sports, so conducting a stopwatch study would be relatively obvious. The WSJ did conduct a similar study on the average Major League Baseball (MLB) game, however, and they found that the average baseball game has 17 minutes and 58 seconds of action in a game that is now an average of 2 hours and 36 minutes long. Punching these numbers into the system, football has an action-to-total-time ratio of approximately 5.7%, and baseball has an action-to-total-time ratio of approximately 11.5%. So, to those who find baseball games in the MLB boring, they actually have a greater, slightly more than double, action ratio than the NFL. We could debate the definition of action, in qualitative vs. quantitative terms, but the numbers don’t lie.

In the WSJ study of baseball, conducted by David Biderman (on baseball) versus the Stuart Silverstein study (on football), they defined the moments of action in baseball to include pitches, plays, and any ball movement. So, in the battle between America’s Pastime, and America’s favorite sport, baseball proves to be the more active sport.

When we break the 192 minutes of the average game down, the truth starts to reveal itself. The average NFL game consists of approximately 63 minutes of commercial breaks, so when watching the average NFL game, roughly 25-33% of our time is spent in a commercial break, according to multiple studies and analysis conducted by WSJ and FiveThirtyEight reports. NFL teams also have a 40-second play clock after most plays, but a 25-second play clock after administrative stoppages, and most NFL teams, on average, snap the ball at the 20-second point. This is the finding, but when I watch games, it seems to me, most NFL teams snap the ball in the single digits. I know there are moments and strategies that call for a hurry-up offense that moves the average, but I’m still surprised at the 20-second average. This finding suggests the NFL fan spends about half of the in-game moments waiting, in anticipatory glory, for the ball to be snapped. Most teams use at least two time outs per half, and the modern NFL viewer at home must endure countless replays, explanations of penalties, the time necessary for trainers to help the injured leave the field, and various other delays in which referees don’t force a team to use a time out. We break all these delays down, and 11 minutes actually starts to make more sense.

When we break the 192 minutes of the average game down, the truth starts to reveal itself. The average NFL game consists of approximately 63 minutes of commercial breaks, so when watching the average NFL game, roughly 25-33% of our time is spent in a commercial break, according to multiple studies and analysis conducted by WSJ and FiveThirtyEight reports. NFL teams also have a 40-second play clock after most plays, but a 25-second play clock after administrative stoppages, and most NFL teams, on average, snap the ball at the 20-second point. This is the finding, but when I watch games, it seems to me, most NFL teams snap the ball in the single digits. I know there are moments and strategies that call for a hurry-up offense that moves the average, but I’m still surprised at the 20-second average. This finding suggests the NFL fan spends about half of the in-game moments waiting, in anticipatory glory, for the ball to be snapped. Most teams use at least two time outs per half, and the modern NFL viewer at home must endure countless replays, explanations of penalties, the time necessary for trainers to help the injured leave the field, and various other delays in which referees don’t force a team to use a time out. We break all these delays down, and 11 minutes actually starts to make more sense.

The Third Spinning Wheel

The overarching question is how did a sport that consists of so many breaks, and so few moments of actual action, become the unquestioned, indisputable most popular sport in America? Author Chuck Klosterman offers many interesting theories and conclusions in his latest book, Football, save for one: Anticipation. He touches on the idea of anticipation being a possible element in the game’s popularity, but he doesn’t explore it sufficiently in my opinion.

There’s only one thing we might love more than action, the anticipation of that action. How many times are we up on the edge of our seat waiting for that game-winning play, only to have our team hand the ball off, up the middle, for a three-yard gain? “Boring!” Julie Ann might say, because she was expecting that crucial play to happen there, but we could say it only heightens the suspense and anticipation for her. When this happens, we know the clock is dwindling, and we might say something like, “C’mon! Let’s go!” as the suspense heightens. At this point, few are sitting when the ball carrier flips the ball to the ref, and the team hurries back to the line. In the next play, the quarterback fakes the ball to the running back (play-action), and he delivers the dagger by sending the ball over the middle to the tight-end for a twenty-four-yard touchdown. This is the only place, right here, where Andrew’s knowledge comes into play. He might have sounded like a football nerd when he tried to explain the need to run the ball up the middle earlier, and no one will laud him for correctly predicting this play tomorrow at work, but when those linebackers stepped up to stop what they feared might be another run up the middle, they accidentally opened a hole behind them that the tight-end stepped into to catch the game-winning touchdown, and Andrew, the enthusiast looked like a genius for predicting how their team would win.

There’s only one thing we might love more than action, the anticipation of that action. How many times are we up on the edge of our seat waiting for that game-winning play, only to have our team hand the ball off, up the middle, for a three-yard gain? “Boring!” Julie Ann might say, because she was expecting that crucial play to happen there, but we could say it only heightens the suspense and anticipation for her. When this happens, we know the clock is dwindling, and we might say something like, “C’mon! Let’s go!” as the suspense heightens. At this point, few are sitting when the ball carrier flips the ball to the ref, and the team hurries back to the line. In the next play, the quarterback fakes the ball to the running back (play-action), and he delivers the dagger by sending the ball over the middle to the tight-end for a twenty-four-yard touchdown. This is the only place, right here, where Andrew’s knowledge comes into play. He might have sounded like a football nerd when he tried to explain the need to run the ball up the middle earlier, and no one will laud him for correctly predicting this play tomorrow at work, but when those linebackers stepped up to stop what they feared might be another run up the middle, they accidentally opened a hole behind them that the tight-end stepped into to catch the game-winning touchdown, and Andrew, the enthusiast looked like a genius for predicting how their team would win.

We can all break down the action of the NFL to 11 minutes, or 30 seconds of crucial action, but one of the reasons the NFL and college football sit atop TV ratings is that the nature of the game leads to a greater sense of anticipation than any other sport. We could also say that football’s low action-to-total-time ratio of approximately 5.7%, compared to baseball’s ratio of approximately 11.5%, leads to more anticipation and a greater sense of excitement when the payoff finally happens. It’s the NFL’s third spinning wheel.

The psychological power of anticipation has led most casinos to adopt what they call the third spinning wheel. It’s no secret that slot machines are the primary money maker for most casinos, but according to Medium.com, slot machines account for 70% of a casino’s revenue. That seems unreasonably high, but the stats back it up. The question is how did casinos make those machines so incredibly addictive? Those of us who’ve dropped play money into slot machines take notice when the first big money maker stops in the first slot, but when that second money maker seductively slides into the second slot, something happens to us. Everything about slot machines are engineered for dramatic effect. The actual outcome was determined the moment we hit the spin button via a Random Number Generator, and our chance of actually winning was determined by the minimum payout percentages set by various state gaming commissions, or tribal compacts. These compacts and commissions say nothing about how casinos can manipulate emotions however, and casinos take advantage of this by having the first “jackpot!” stop in the first slot almost immediately after we press spin, the second jackpot can take approximately 2-3 seconds, but it’s that third one that is deliberately delayed to induce prolonged anticipation. It can take up to five seconds to stop. What happens to us in those five seconds? How many dreams and aspirations can occur in five seconds?

The psychological power of anticipation has led most casinos to adopt what they call the third spinning wheel. It’s no secret that slot machines are the primary money maker for most casinos, but according to Medium.com, slot machines account for 70% of a casino’s revenue. That seems unreasonably high, but the stats back it up. The question is how did casinos make those machines so incredibly addictive? Those of us who’ve dropped play money into slot machines take notice when the first big money maker stops in the first slot, but when that second money maker seductively slides into the second slot, something happens to us. Everything about slot machines are engineered for dramatic effect. The actual outcome was determined the moment we hit the spin button via a Random Number Generator, and our chance of actually winning was determined by the minimum payout percentages set by various state gaming commissions, or tribal compacts. These compacts and commissions say nothing about how casinos can manipulate emotions however, and casinos take advantage of this by having the first “jackpot!” stop in the first slot almost immediately after we press spin, the second jackpot can take approximately 2-3 seconds, but it’s that third one that is deliberately delayed to induce prolonged anticipation. It can take up to five seconds to stop. What happens to us in those five seconds? How many dreams and aspirations can occur in five seconds?

“I was SO close!” we complain to our friends. “Look at that,” we say, pointing to the two big money makers followed by the taunting cherry in the three hole. We had three-to-five orchestrated seconds of watching that third wheel spin in which we realized that all of our unreasonable dreams could come true. What we don’t know is that those three-to-five seconds are the result of the psychological research casinos commission to maximize our sense of anticipation. They do that with an orchestrated near-miss, or the “I was SO close!” moment that leads to maximum engagement from the customer. We think our machine is ready to pop, and we’re not about to let some other slot player come in and take over, because we’ve paid our dues watching nothing happen for as long as we think it takes for a machine to pay off. Those of us who play slots don’t take into account how much time and money casinos have put into understanding us better. We don’t know that they’ve found how much impact that third-spinning wheel has on us. They’ve determined that if they provide us too many near-misses, they can reduce the impact of the third-spinning wheel (translation: we’ll figure it out). They’ve also found that too few of them often makes our near-misses less effective (translation: we’ll get bored). Their expensive, ever-changing, and ever-adapting research has found that if they give us a third-spinning wheel 30% of the time, that’s the Goldilocks number to manipulate our minds and maximize our engagement. They’ve also found that being “SO close!” to winning is actually more exciting than winning, depending on how much we win of course. It’s all about the power of anticipation.

Unlike slot machines in casinos, the game of football is not coordinated to capitalize on our love of anticipation, but the nature of the game lends itself to maximized anticipatory enjoyment.

As with the other side of the casinos psychological research, basketball and hockey have so much action going on that it can diminish the drama of most plays. There’s so much action going on that when an incredibly exciting play finally happens, we often have to rewind the broadcast to see what just happened, because we accidentally tuned the game out for a while. As Klosterman writes, we love action movies, but some action movies actually have too much action, and we accidentally tune out some of the action scenes that led to the big whopper, final conflict. Klosterman also alludes to the idea that football, and its 11 minutes of action, also incidentally provide talking time between moments of action, which makes it an excellent sport for group settings such as family and friendly get-togethers. On that note, I know baseball provides more moments of action, according to the WSJ study, but I find myself talking to friends so often during baseball games that by the time the action finally takes place, I’m so absorbed in the conversation that I completely lose track of the game. (This might be a problem inherent in the game of baseball for another conversation.)

The NFL will probably never change its formula, because why would they? They’re the king of the hill, top of the heap, and they can charge advertisers pretty much whatever they want. That formula has tested the patience of even the most enthusiastic fan, as most of us hate commercials, the delays now inherent in the review process, and all of the other delays the game now provides, but I found three glorious letters that freed me from my pain, D,V, and R. It’s not foolproof, as some of our friends will text us incidental hints or outright revelations (no matter how often we tell them not to), and we’ll have to be the type who can watch a game knowing it’s already over (some weirdly cannot do this). If we can overcome those low hurdles, we’ll be able to watch most games break-free if we give them a head start of between 50-90 minutes. I usually go high-end, so I don’t have to endure sideline reporters and any banter between the play-by-play broadcaster and the analyst. The DVR also frees me from the time it takes for a referee to review a reviewable play, discuss that review with his fellow referees, and administer the effect of his findings (expedited reviews have cut down on this process, but it’s still not enough for me). Thanks to the VCR, and now the DVR, I haven’t watched an NFL game live (save for those at get-togethers) for decades, because I know those in charge of the most popular game, in the United States anyway, are not going to change, because why would they? I also disagree with Chuck Klosterman’s thesis that the NFL is doomed. Unless something unforeseen happens, I predict its dominance will almost surely continue for generations beyond the point that my generation assumes the temperature, generally between 50-55 degrees Fahrenheit, that maggots anticipate.