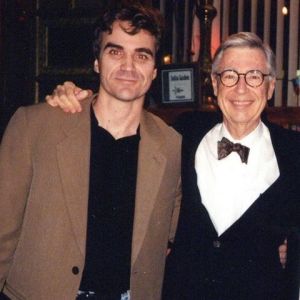

When Tom Junod’s editor commissioned him to write a 400-word bio on Fred Rogers from the wildly popular kid’s show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Tom Junod thought BIG. He wanted to write a big scandal piece based on what he uncovered, or at the very least he wanted to compile a bunch of little things in an exposé that revealed the character of the main character of the show was a big old fraud. “Isn’t it my job to tell my audience that everything they love and cherish is an absolute fraud?” is the modus operandi of most modern reporters, and Junod had a history of exposing celebrities in his history of reportage. Whatever goes up must come down. “You build them up, and I’ll tear them down.”

In A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood the actor playing reporter Tom Junod saw it as his job to expose the beloved Mister Rogers as a fraud. At this point in Junod’s career, Junod was the dictionary definition of the cynical reporter bent on uncovering unsavory characteristics about his subjects. “These people are not my friends,” the actor playing Junod says in reaction to his editor telling him that the reason she assigned him to interview Fred Rogers was that no one else would speak to Junod. At this point in his career, Junod had a bad reputation of exposing the warts of the subjects he covered.

The nature of his defense was, “Isn’t it my job to report on these people, warts and all? If the American public doesn’t want to see the warts, they need to see them. Shouldn’t I focus on the unsavory elements of the subjects I interview? Isn’t that the modus operandi of the serious reporter?” Ton Junod, like so many cynical and broken people, want to destroy institutions one person at a time. We give them awards, we make docudramas that memorialize their plight, and we can now repeat the inconsistencies they discovered at the drop of the subject’s name.

These themes lay the foundation for Junod’s mission to try to destroy Mister Rogers. At one point in the film, we hear Junod openly state that he thinks Mister Rogers is a fraud, and that he thinks it’s his job to expose him. After his initial interview with Mister Rogers is cut short, Junod complains that Rogers and his people aren’t giving Junod enough time to interview Rogers properly. His complaint feeds into our general suspicions that anytime a reporter seeks to interview a subject that subject, and his handlers, are going to do anything and everything to protect the reputation of the subject, particularly when their main character is on a children’s show.

We suspect, along with Junod, that Rogers and his people, know Junod, and we suspect that they advise he give Junod short, evasive answers to prevent Rogers from slipping up and revealing everything they want/need to hide. Even though the movie doesn’t go to great lengths to portray Junod’s frustration, we suspect that Junod probably asked Rogers and his people, “What are you hiding?” In a turnabout from what Junod was probably accustomed, Fred Rogers personally creates more time for Junod. This leads to a series of interviews in which Mister Rogers begins asking Junod questions about his life.

“I’m supposed to be interviewing you,” Junod says at one point. Again, Junod and the rest of us know that subjects use many rhetorical tactics to protect themselves, and this tactic sounds a lot like obfuscation. Fred Rogers answers some of Junod’s questions throughout, but we can only guess that the cynical, seasoned reporter has witnessed a wide array of rhetorical tactics subjects use to avoid answering questions, and he believes Rogers is engaging in them when Rogers continues to ask Junod questions. We can also guess that the actual interaction between the two men grew more heated than the movie portrays, as Junod attempted to expose Mister Rogers’ inconsistencies. The interesting turnabout happens when Junod realizes that Fred Rogers isn’t using rhetorical tactics, as he pokes and prods, and that the man genuinely cares about this self-described broken man named Tom Junod. The movie doesn’t involve the usual tropes that most on-screen exchanges do in which one of the two parties eventually experiences an obvious epiphany. It depicts Rogers as a somewhat naïve character who genuinely believes in what he’s saying, and he reinforces that notion with his answers. The implicit suggestion of these exchanges are that Rogers continues to ask Junod leading questions, because he genuinely cares about the broken man before him in the manner he cares about most complete strangers, and that implies that his care for children is just as genuine.

“I’m supposed to be interviewing you,” Junod says at one point. Again, Junod and the rest of us know that subjects use many rhetorical tactics to protect themselves, and this tactic sounds a lot like obfuscation. Fred Rogers answers some of Junod’s questions throughout, but we can only guess that the cynical, seasoned reporter has witnessed a wide array of rhetorical tactics subjects use to avoid answering questions, and he believes Rogers is engaging in them when Rogers continues to ask Junod questions. We can also guess that the actual interaction between the two men grew more heated than the movie portrays, as Junod attempted to expose Mister Rogers’ inconsistencies. The interesting turnabout happens when Junod realizes that Fred Rogers isn’t using rhetorical tactics, as he pokes and prods, and that the man genuinely cares about this self-described broken man named Tom Junod. The movie doesn’t involve the usual tropes that most on-screen exchanges do in which one of the two parties eventually experiences an obvious epiphany. It depicts Rogers as a somewhat naïve character who genuinely believes in what he’s saying, and he reinforces that notion with his answers. The implicit suggestion of these exchanges are that Rogers continues to ask Junod leading questions, because he genuinely cares about the broken man before him in the manner he cares about most complete strangers, and that implies that his care for children is just as genuine.

Tom Junod’s final report does not culminate in a finding that leads to scandal, and he is not able to uncover an inconsistency that reveals what is wrong with Mister Rogers. Instead, he writes a story titled Can you say Hero? that thematically asks what could be a semi-autobiographical question, what is wrong with us? Why do we want/need to see the warts? Why do we need to complicate our heroes with inconsistencies that lead us to think/know that they’re actually frauds? Is there a part of us that thinks everyone and everything is fraudulent, and do we somehow enjoy the idea that we were once so naïve that we believed in them? Some of us enjoy the ‘I got nothing to believe in’ narrative, because it suggests that we’re so knowledgeable that we simply can’t believe in anything anymore, and we pity those who do because they’re just not very informed. As such, we enjoy it when reporters strip away the glossy varnish we all know to uncover dulled, dirty facts that lead to a much more comfortable suit of cynicism. We call these details facts, and the accumulation of facts, knowledge, and knowledge is power.

Throughout the movie, and the Junod story on which it’s based, we learn that Junod was unable to uncover the big scandal, and he discovered that there wasn’t some big exposé beneath the rubble of the Fred Rogers character. Did Junod initially believe that he didn’t do his job well enough? Did he, after conducting exhaustive interviews with everyone who knew, loved, and worked with Rogers, initially believe that the fortress around Rogers was fortified with loyal subjects who wouldn’t give up the dirt on him? We have to think this plagued Junod initially, even if the movie didn’t cover this section. In his search for something big, Junod eventually uncovered some very little things about Fred Rogers. These revelations developed over time, incrementally, through incidents. The movie portrayed these incidents as those Junod experienced firsthand, but research shows that he learned about them secondhand, through the numerous interviews Junod conducted. The consistency of these seemingly exhaustive interviews led Junod to a startling revelation: Fred Rogers and Mister Rogers might be one and the same, and they might be, could be real. Junod poked and prodded Rogers and everyone who knew him, until he came to the conclusion that Fred Rogers might be “the nicest man in the world”.

The reason I love this angle in this movie is that we all know and enjoy “the story” of the nicest man in the world, who has an “inconsistency” of some sort that evolves into a narrative we can recite at the mere mention of the man’s name. “Kids love him, and their parents love him, because of how much their kids love him, but we now know, thanks to Junod’s exposé on him that it’s all based on a lie?” We love that facts=knowledge, and knowledge is power angle, and we prefer that angle. We love reporters who remove a brick from our foundation to reveal them, us, and all of the institutions in between as absolute frauds. We grew to love and admire the various screen stars who, in some small ways, helped shape who we are today, and we all love to learn, in a bittersweet way, that it was all based on a big lie. Either that or we enjoy seeing those who portray themselves as a paragon of virtue torn down, so we don’t have to feel so inferior in that regard. As Junod’s bio on Fred Rogers details, he couldn’t find that angle that would’ve and could’ve destroyed everything Fred Rogers built. He couldn’t produce that devastating exposé to win that loyalty, love and awards from his peers for tearing down the American institution that was/is Mister Rogers. What he found instead was a man named Fred Rogers, whom he called “the nicest man in the world”.

Tom Junod later summarized his time with Mister Rogers in a piece for the Atlantic, “In 1998, I wrote a story about Fred Rogers; in 2019, that story has turned out to be my moral lottery ticket,” Junod wrote in The Atlantic. “I’d believed that my friendship with Fred was part of my past; now I find myself in possession of a vast, unearned fortune of love and kindness at a time when love and kindness are in short supply.”

My takeaway from the legacy of Mister Rogers, or Mr. Fred Rogers, as presented by the movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, is that he was a great man. Mr. Fred Rogers also helps some of us define what a great man is. Our typical narrative is that the great man does great things, i.e. big things. The great men of the past discovered penicillin, helped eradicate hunger, or proved a decisive leader on the world stage when the world needed a powerful leader to save the world. Mr. Fred Rogers didn’t do anything that would qualify him as a great man in these terms, but he did a whole bunch of little things, every day, that when we compile them, we could call big, transformative, and even huge. The impact he made largely involved one-on-one conversations with children, and if you ever watched his show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, you know those conversations were one-on-one.

My takeaway from the legacy of Mister Rogers, or Mr. Fred Rogers, as presented by the movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, is that he was a great man. Mr. Fred Rogers also helps some of us define what a great man is. Our typical narrative is that the great man does great things, i.e. big things. The great men of the past discovered penicillin, helped eradicate hunger, or proved a decisive leader on the world stage when the world needed a powerful leader to save the world. Mr. Fred Rogers didn’t do anything that would qualify him as a great man in these terms, but he did a whole bunch of little things, every day, that when we compile them, we could call big, transformative, and even huge. The impact he made largely involved one-on-one conversations with children, and if you ever watched his show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, you know those conversations were one-on-one.

For everything Fred Rogers accomplished in life, and for all of the absolute goodness he presented to children and helped spread, his greatest accomplishment may have been that he mastered the art of being present. Being present might sound like a foo foo term, because it is, but it’s also about the simple art of listening to another without distraction. It’s about making a concerted effort, often a more natural and more organic form of distraction-free listening. The next question you have is how can we put forth a concerted effort to be more natural and more organic at anything? Aren’t those basically antonyms? Yes, but when one puts forth a concerted effort to be more natural and more organic anything, they can give the impression that they are naturally gifted and more organic.

Being present, for example, is not a gift one accrues as a gift. It’s not, as far as we know, a particular ingredient available to some in their DNA and unavailable to others. If your parents were great listeners and present, it has no bearing on your abilities or faults in this regard. It is more a learned art to momentarily forget about all the big stuff, for just a moment, to concentrate and focus on the little. When Mister Rogers talked with children, he listened to them with the same level of acuity he did with adults, and he didn’t follow the typical bullet points of adults talking to children, or the prototypical and successful formula of adult personalities on a children’s show talking to children that now appears so condescending compared to the manner in which Fred Rogers spoke to them. Fred Rogers didn’t talk to these kids as if they were cute or precocious, and he didn’t attempt to draw that cuteness out to make them cuter for the enjoyment of any adults watching. Fred Rogers spoke to them in a manner that didn’t remind any of us of the way we to talk to children. He just talked to them.

We could see how this affected the kids on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood when Fred Rogers listened to them. It caught them off guard. Our initial reaction to their open-mouthed awe is that they’re suffering some stage fright. Not only are they on a stage, they have a mess of kids behind them, and they’re also on TV. Who wouldn’t experience some stage fright? As their conversation continues, the kids slowly meld into the Mister Rogers conversation. They’re shocked that he is listening to them, and they’re further shocked that he is giving weight to what they say. Why are they shocked? Fred Rogers acted different from every adult they’ve ever met. Kids and pets adjust to our patterns, our rituals, and our habits. When we act in a way somewhat different from that, they notice. When Fred Rogers listened to their stories, their ideas, and their complaints, it was so different that every kid in the room noticed, and they wanted to speak to him.

Most of adults go big, and the bigger the better. We want a huge resume in life before we call it a day. More money and better status equal a better life. To achieve bigger things, we must learn to multitask. We can define the difference between a good employee and a suboptimal one on their ability to multitask. Some are better at it than others are, and depending on what they do, multitasking might be required, but how many of those tasks do we accomplish at optimum efficiency? Do the results of some tasks suffer in lieu of others when you’re multitasking, or are you just that much better at it than I am? It’s impossible to know the totality of a man from movies, books, magazine articles, and various YouTube, but from what I gathered Fred Rogers was the opposite a multitasker.

Anybody who lived during the era of Mister Roger’s Neighborhood knew and loved the creative and elaborate intros of the various children’s shows. Some of us loved those intros so much that that was all we watched. There were explosive graphics, great music to accompany those graphics, quick screen switches, and a healthy dose of fast movement to captivate us. The intro to Mister Roger’s Neighborhood involved a man changing his shoes while singing a dumpy, simple song called Won’t you be My Neighbor? The pace of Fred Roger’s creation was as purposefully simple, disturbingly quiet, and as painfully slow as that intro, and those of us with varying levels of ADD or ADHD couldn’t watch the show even when we were Fred Rogers target audience. Everything about the show bothered us so much that when Eddie Murphy devised the Mister Robinson’s Neighborhood skit, we were laughing harder than anyone else. For most of us, Mister Rogers Neighborhood was a great premise for a joke. The movie A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood and HBO’s Won’t you be my Neighbor reminds us of the big things that led us to tune him out and the little things that annoyed us, and they informed us of Fred Roger’s little and big theme.

Actor Tom Hanks said he watched hundreds of episodes of Mister Rogers Neighborhood to prepare for his role in the movie, before he realized Fred Rogers created the show for children. As the comedian that he is, Tom Hanks left the ironic, obvious punchline as a standalone after he received a laugh. If he continued, I think he would’ve said that every minute and ever second of Fred Rogers’ creation was devoted to children. Fred Rogers took great pride in how quiet his show was, for example, and when he spoke, his tone was so measured we could almost hear the punctuation fall into place. Linguists say that our ums and ahhs are quite useful, because they help listeners follow our sentences better. Fred Rogers didn’t um and ahh, but his tones were so carefully measured and methodical that those of us with ADD and ADHD couldn’t watch his show. We wanted him to finish his sentences quicker. When he told us he was feeding his fish, it drove us nuts. “Just feed the fish!” we screamed at our TV. There was a method to this madness. He developed this routine after a blind child wrote him to say she was worried that he wasn’t feeding his fish. He fed the fish, as part of his introduction on the show, but she didn’t know it. So, he began telling his audience that he was feeding his fish. Then, there was the silence.

Watch an adult show on cooking, making things with tools, or anything that involves a methodical process, and you’ll see them skip certain, obvious parts of the process. They will list the ingredients, inform us how to mix, slice and dice, and cover all of the methodical steps in the process, then they’ll show us the finished product. They skip the obvious and tedious parts of the process. Mister Rogers didn’t skip anything. If he brought in an expert on how to build or fix something, there were long periods of silence involved in the process. This drove some of us nuts, but it was a carefully orchestrated part of the show, designed to help children understand the methodical, quiet approach needed to build things.

Some cultural writers state that the approach of Mister Rogers Neighborhood, and Fred Rogers personal approach, suggest that he was anti-consumerism. While I don’t doubt that, I don’t think there is direct correlation to the idea that Fred Rogers was an anti-capitalist. I don’t think he was anti-capitalist or pro-capitalism. As with everything Fred Rogers did, his stance was all about children. He directed his ire at marketing, and marketing to children specifically. I don’t think he minded when an XYZ company would say that their product was better than their competition’s product, for example, in a pure marketing ploy. What bothered Mr. Rogers was this idea that some marketing ploys lead people (children in particular) to feel shame. I think he disliked this idea that some marketing ploys encourage children to think they need the latest and greatest toy, and I think he abhorred the idea that another child might feel a sense of shame for being stuck with what some marketing ploys encouraged them to believe was an “inferior” toy. I think he detested the idea that marketing arms created the need kids felt to have more products and better products than their friends, and if they didn’t, they felt incomplete. I think his concern for children was was unfettered by anti-capitalist. pro-capitalist ideals, or anything ideological. It can be difficult for a cynic like Tom Junod, this writer, or anyone else reading this to believe, but I believe Fred Rogers’ concern for children consumed him, affected his every thought and action in a way that proved apolitical.

My favorite illustrative moment occurred when Fred Rogers saw a very young boy wearing battle gear. Adults might wear T-shirts that have strong messages to inform our peers that we’re strong on the inside, but most of us don’t wear Masters of the Universe battle gear anymore. Our natural reaction is to consider it cute when we see kids all decked out in costume battle gear. When Fred Rogers met this kid, the kid immediately showed Fred Rogers his sword. Fred examined the sword and complimented him on it. Other than that, Fred spoke to the child in the manner he spoke to all kids. This child refused to break character, as it were, no matter how nice Fred Rogers was to him. The young child refused to show any of the signs of endearment to which Mister Rogers was more accustomed from children. This bothered the kid’s mother, as she feared Rogers might perceive her child as rude. This did not bother Mister Rogers in the least. After the child’s mother failed to convince her child to say something nice to Mister Rogers, Fred Rogers leaned in on the kid and whispered something in the child’s ear. When asked what he whispered, Fred Rogers replied:

“Oh, I just knew that whenever you see a little boy carrying something like that, it means that he wants to show people that he’s strong on the outside. I just wanted to let him know that he was strong on the inside, too. Maybe it was something he needed to hear.” If you’re anything like me, you read such a line and marvel at its profundity, the big bold word profound, but I can only imagine that Fred Rogers didn’t deliver it that way, or repeat it to others in the manner the rest of us do when we’ve said something profound. I imagine that it was just a little thing Fred Rogers thought up in the moment, because he thought it was something that kid needed to hear.

Mister Rogers Neighborhood wasn’t a big show, and A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood wasn’t a big movie. They focused on the little things, the little things Fred Rogers did, and the little thing’s theme of Fred Rogers life. These ideas run counter to the whole idea some of us have to ‘go big or go home’. One of the many profound things Fred Rogers said was we shouldn’t get so tied up in trying to accomplish big things that we forget about the little things. “There’s nothing wrong with you, if you don’t accomplish stupendous things,” he said in various ways. “I like you just the way you are.”

Mister Rogers Neighborhood wasn’t a big show, and A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood wasn’t a big movie. They focused on the little things, the little things Fred Rogers did, and the little thing’s theme of Fred Rogers life. These ideas run counter to the whole idea some of us have to ‘go big or go home’. One of the many profound things Fred Rogers said was we shouldn’t get so tied up in trying to accomplish big things that we forget about the little things. “There’s nothing wrong with you, if you don’t accomplish stupendous things,” he said in various ways. “I like you just the way you are.”

How many of us like our friends and family members just the way they are? How many of us want more from those around us? How many of us like ourselves just the way we are? If someone approached us and said, “Don’t you want more from life? I really think you’re going to regret the fact that you didn’t strive for more in life.” What if we said, “I like myself just the way I am.” They would probably dismiss that comment as an excuse to be lazy, an excuse to avoid broadening ourselves onward and outward, or they would think that we’re just being obnoxious. It does sound like an obnoxious reply, unless you’re the host of child programming. I mean, who likes themselves so much that they’re just going to keep doing what they’re doing for the rest of their lives? They’re never going to strive for more? The obnoxious could reply that their interrogating friend probably doesn’t like themselves very much, and they think that striving for more, for a better definition of success, or a definition of something they think they might eventually like better.

Most people don’t think this way at the end, according to health care workers who sit bedside as dying patients issue their last words. Most dying patients, they say, regret living the lives others told them to live. “I wish I’d lived my life the way I wanted, not how others expected me to behave.” This could be anecdotal evidence of the human experience, of course, or it could be indicative of the idea that most of us wish we had the courage to like ourselves just the way we are, and we wish we had the courage to defy others’ expectations of us and live the way we want to live. Imagine if that certain someone we like, love, and respect most said something along the lines of: “I have no problem with you striving for more, being the best you can be and all that, but before you go about doing all that, I just wanted you to know that I like you just the way you are.” Now imagine you, being on the other side of that paradigm saying that, however you want to say it, to someone else. Is it better to give such a compliment or receive? Again, I see Fred Rogers way of viewing the world as profound, but I have to imagine if I had the chance to ask Fred Rogers about it, he would downplay it saying, “It’s just a little thing I say to help children feel better about themselves.” It was a little thing he said, but if we all attended to the little things better and more often, for the rest of our lives, as we fortified our connections to the little people around us, who are just like us, I have to imagine that all those little things could roll up into something big.