“The thing about being human is,” Bob Peters said to initiate a conversation with my friend Arnold Glass.

“No, I am human,” Arnold said. “I’m standing right before you, two arms, and two legs just like you.”

That was funny, I thought, examining Arnold’s face for a break that would reveal the joke. It wasn’t award-winning funny, or even knee-slapping funny, but I considered it a fairly decent trap to set for Bob Peters for future jokes. Depending on where he took it from there, I thought he laid some pretty decent groundwork. The three of us were co-workers at a company, on break, shooting the stuff. I didn’t know Bob Peters. He was kind of a floater, who moved from person to person, group to group, but I thought I knew Arnold. We were co-workers who spent so much time around each other that I suppose I could’ve call him a best friend at work, but that just seems like such a grade school/high school designation. It just feels odd to call a grown man that I didn’t know before we started working at the same company a best friend, but we did a lot together over the years. Arnold could be funny occasion, but he was more knock-knock joke funny. This level of dada comedy, or what I thought might be intentionally irrational comedy without a base or direction was so out of character for him that I thought he might follow it up with, ‘Sorry, that just sounded like something to say. It didn’t work as well as I thought it would.’ Not only did Arnold not say something like that or give any cues that he was joking, he was all bowed up. I was almost positive that he wasn’t looking to throw down, during a 15-minute break on company grounds, over something as odd as this, but he looked so defensive. What an odd thing to say, I thought, and what a weird thing to get defensive about.

That was funny, I thought, examining Arnold’s face for a break that would reveal the joke. It wasn’t award-winning funny, or even knee-slapping funny, but I considered it a fairly decent trap to set for Bob Peters for future jokes. Depending on where he took it from there, I thought he laid some pretty decent groundwork. The three of us were co-workers at a company, on break, shooting the stuff. I didn’t know Bob Peters. He was kind of a floater, who moved from person to person, group to group, but I thought I knew Arnold. We were co-workers who spent so much time around each other that I suppose I could’ve call him a best friend at work, but that just seems like such a grade school/high school designation. It just feels odd to call a grown man that I didn’t know before we started working at the same company a best friend, but we did a lot together over the years. Arnold could be funny occasion, but he was more knock-knock joke funny. This level of dada comedy, or what I thought might be intentionally irrational comedy without a base or direction was so out of character for him that I thought he might follow it up with, ‘Sorry, that just sounded like something to say. It didn’t work as well as I thought it would.’ Not only did Arnold not say something like that or give any cues that he was joking, he was all bowed up. I was almost positive that he wasn’t looking to throw down, during a 15-minute break on company grounds, over something as odd as this, but he looked so defensive. What an odd thing to say, I thought, and what a weird thing to get defensive about.

Bob Peters obviously dismissed Arnold’s comment as nothing more than an obnoxious attempt to interrupt him before continuing, “As I was saying-”

“No,” Arnold interrupted, growing uncharacteristically confrontational. “You called me out here. I’m a human being with all the same hopes and dreams as you. I’m going to need you to acknowledge that before you continue.”

“Fine, I acknowledge that you are a living, breathing human being with all the same hopes and dreams as the rest of us,” Bob Peters said. “Now, can I continue?”

***

“What was all that about?” I asked after Arnold and I finished our conversations with Bob Peters, and he walked back to the office.

“Cripes, I forgot to apologize to Bob for all that didn’t I,” Arnold Glass said. “He just happened to step on one of my land mines, but he didn’t mean anything by it did he?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t think so. I think he just thought it was a clever intro … but what do you think he meant by it?”

“I don’t know. It’s that name thing,” Arnold said. “I thought Bob was trying to be funny, but now that I think about it, I’m not sure Bob even knows my last name. I know I don’t know his. We’re not on a last name basis.”

“Peters,” I said. “Bob Peters.”

“Okay, Peters. Well, God bless him for having such a normal last name.”

“Glass? What’s wrong with Glass?”

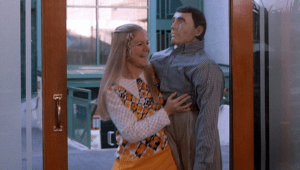

“We’ve never talked about this?” Arnold asked me with some fatigue. “You obviously didn’t grow up watching The Brady Bunch, did you?” I said I had, and the name George Glass immediately came to mind, but I feigned ignorance. “There was an episode where Jan Brady made up an imaginary boyfriend. When she was pressed for his name, she said, “George,” and then she looked around and saw a glass of water. “George Glass,” she said.”

“Okay, yeah, I remember that.”

“I’ve had nightmares about that scene.”

“You’ve got to be joking?” I asked with suspicious but confused laughter.

“I’m not. I’m really not,” Arnold said with a most serious face. “We were all too young to know the episode when it first came out, but, you know, reruns. I might’ve been in 2nd grade when Mary Beth Driscoll said, “Are you even real?” I didn’t get it, because I never saw the episode, so she explained it. I didn’t think it was funny, but everyone else did. Everyone else did, and they joined in on the joke. It hurt a little, but mainly because I didn’t understand it. Then, every time they reran that episode, I’d get some semblance of that joke, and I probably took way too personal, but I was young, real young, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. ‘We’re just joking, for gosh sakes Arnie’ they’d say, and that never made it any better. Things like that are stupid, insignificant, and irrelevant, until they start to gather moss. Every time you meet a friend’s mom, they ask if you’re real, or they say it’s nice to finally meet you. We thought you were fake. It sort of petered out after a while. The harmless and stupid jokes never ended, but I didn’t hear them as often for quite a while there, until the 1996 movie A Very Brady Sequel came out, and then the internet picked that whole joke up as a meme for imaginary boyfriends, girlfriends, and imaginary friends, and it started all over again.”

“I’m not. I’m really not,” Arnold said with a most serious face. “We were all too young to know the episode when it first came out, but, you know, reruns. I might’ve been in 2nd grade when Mary Beth Driscoll said, “Are you even real?” I didn’t get it, because I never saw the episode, so she explained it. I didn’t think it was funny, but everyone else did. Everyone else did, and they joined in on the joke. It hurt a little, but mainly because I didn’t understand it. Then, every time they reran that episode, I’d get some semblance of that joke, and I probably took way too personal, but I was young, real young, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. ‘We’re just joking, for gosh sakes Arnie’ they’d say, and that never made it any better. Things like that are stupid, insignificant, and irrelevant, until they start to gather moss. Every time you meet a friend’s mom, they ask if you’re real, or they say it’s nice to finally meet you. We thought you were fake. It sort of petered out after a while. The harmless and stupid jokes never ended, but I didn’t hear them as often for quite a while there, until the 1996 movie A Very Brady Sequel came out, and then the internet picked that whole joke up as a meme for imaginary boyfriends, girlfriends, and imaginary friends, and it started all over again.”

I could’ve, and probably should’ve, expressed some sort of sympathy, but I couldn’t help but find it so harmless that it was cute and cute-funny. The general idea of a man being mentally badgered about anything calls for a sympathetic response, but to hear someone say that a Brady Bunch joke was the source of his pain was so unprecedented that I couldn’t help but find humor in it. I managed to keep a straight face, a solemn, sympathetic face, until he said:

“I’ve even considered changing my name more than once. I’m serious. Totally serious,” he added when I ‘C’mon’ed him’. “If my dad didn’t talk me off that ledge, talking about breaking the long, storied history of the Glasses, and their proud British heritage, I would’ve gone through with it.”

“I’m sorry,” I said when I laughed. “It’s just the words breaking the Glass got to me,” I confessed. Those words weren’t funny, but it didn’t take much to tip me into laughter, and I considered it a decent excuse for laughing.

“It’s really not funny, and it’s not a joke,” Arnold said defensively. “When I was in my teens, and I’d meet my girlfriends’ families, their sisters would jab me in the shoulder with their finger and say things like, “I just wanted to make sure you were real.” Another person, a mom, a nice, sweet maternal mom said, “We thought it was like that time Jan Brady made up a boyfriend, and she said his name was George Glass. We thought Julie did that with you. Sorry, but we thought she made you up.”

“It’s really not funny, and it’s not a joke,” Arnold said defensively. “When I was in my teens, and I’d meet my girlfriends’ families, their sisters would jab me in the shoulder with their finger and say things like, “I just wanted to make sure you were real.” Another person, a mom, a nice, sweet maternal mom said, “We thought it was like that time Jan Brady made up a boyfriend, and she said his name was George Glass. We thought Julie did that with you. Sorry, but we thought she made you up.”

“My guess is that’s probably happened a million times,” I said after I achieved some level of control. “Nerdy girls and boys have made up boyfriends and girlfriends since, probably since the cavemen.”

“I get that,” Arnold said, “and if it happened once or twice, I’d say it’s only happened once or twice, and that’s normal, as you say, but it’s happened so often that … that you can’t help but question your identity and your existence.”

“Your existence?”

“Well, I never thought I wasn’t real, if that’s what you’re asking,” Arnold Glass said, “but these things, these little tiny, and seemingly insignificant things, can have a cumulative effect that can, regrettably, end up all over someone like Bob. Remind me to apologize to him when I see him.”

“Example?”

“Example, let’s see,” Arnold said. “Well, there’s nothing wrong with your nose. Let me make that clear, because I’d hate to put you through what I’ve been through. I mean it’s not too long, too big, or crooked. You have a very normal nose on your face, but imagine if someone joked that there was something wrong with it. Imagine if it was nothing more than a dumb, insignificant and untrue comment on your nose. You’d tell them to shut up, or some variation thereof that allows you to swat their comment away, like a pesky mosquito. Now imagine that someone else, someone who had no relation to that first person, says the same exact thing. You might start to think there’s something to it. You might be a little paranoid about your nose, right? Maybe? Now imagine that this silly, stupid thing is the same thing your grade school peers hit you with when you were young, very young, too young to know how to deal with it properly. It has a way of chasing you into adulthood, until you’re impulsively launching on someone like Bob. Do you think it could lead to a cumulative effect equivalent to wanting to change your name, like getting a nose job or something? And the whole time, you know you have a perfectly normal nose, because everyone says there’s nothing wrong with your nose, like I had a perfectly normal name, until some writer on some stupid show decided your last name would be the perfect name for an imaginary person.

“Example, let’s see,” Arnold said. “Well, there’s nothing wrong with your nose. Let me make that clear, because I’d hate to put you through what I’ve been through. I mean it’s not too long, too big, or crooked. You have a very normal nose on your face, but imagine if someone joked that there was something wrong with it. Imagine if it was nothing more than a dumb, insignificant and untrue comment on your nose. You’d tell them to shut up, or some variation thereof that allows you to swat their comment away, like a pesky mosquito. Now imagine that someone else, someone who had no relation to that first person, says the same exact thing. You might start to think there’s something to it. You might be a little paranoid about your nose, right? Maybe? Now imagine that this silly, stupid thing is the same thing your grade school peers hit you with when you were young, very young, too young to know how to deal with it properly. It has a way of chasing you into adulthood, until you’re impulsively launching on someone like Bob. Do you think it could lead to a cumulative effect equivalent to wanting to change your name, like getting a nose job or something? And the whole time, you know you have a perfectly normal nose, because everyone says there’s nothing wrong with your nose, like I had a perfectly normal name, until some writer on some stupid show decided your last name would be the perfect name for an imaginary person.

“See, what you saw was a one-time, seemingly insignificant incident,” Arnold continued. “But you didn’t see the buildup, the accumulation, and you probably just think it was bizarre, and all that, but it was the result of a cumulative effect. Have you ever heard of the Chinese Water Torture effect? They strapped a guy into a chair so tight, he couldn’t move, under a slowly dripping water faucet. Now, we can drop anywhere from one droplet of water to a million drops of water on a person’s forehead, and it won’t cause any physical damage to that forehead, but psychologically? Psychologically, it’s been documented as one of the most cruel, brutal, and inhumane forms of torture ever invented. Why? It is the accumulation of seeing the next drop of water, knowing it’s going to hit your head, and it finally hitting. It’s the same thing here, but my slow drip has occurred over the years, the decades, and it can manifest in ways you saw today with Bob Peters. Some say it can be stressful to the point of panic-inducing attacks. That’s never happened to me, those final stages, but it could. Some say it could.”

I still couldn’t see it, and in many ways I still can’t. The whole idea of it obviously still fascinates me, but no matter how well Arnold researched what happened to him that led him to his unusual outburst, and how persuasive he was in the moment, I still couldn’t wrap my arms around the idea of what he described as a cumulative effect, even under the umbrella of Chinese Water Torture effect. It was hard to see through the bizarre, silliness of the idea, and it’s still difficult for me to wrap my mind around the idea that a person could be so damaged by a Brady Bunch joke that he’s reflexively lashing out at anyone who even hints that he might not be real, imaginary, or in this case not human. The only thing I can come up with is it’s the difference between sympathy and empathy. Sympathy is something we feel for someone experiencing something foreign to our experience. Empathy is almost a shared sentiment we have for someone who is experiencing something for which we experienced ourselves to such a degree our knowledge of it can be intimate, and the only people who can understand The Brady Bunch Glass effect are those who have experienced themselves.