As horrific as the murders and mysterious deaths surrounding Annie Cook were, they pale in comparison to the detailed account her niece, Mrs. Mary Knox Cauffman, provides of the physical and mental torture she experienced on a daily basis at the hands of that unusually awful woman.

“Oh no, I can’t talk about it,” Mary Knox Cauffman informed Evil Obsession author Nellie Snyder Yost. “I don’t even want to think about it.”

“Oh no, I can’t talk about it,” Mary Knox Cauffman informed Evil Obsession author Nellie Snyder Yost. “I don’t even want to think about it.”

Ms. Yost was standing before Mary’s door informing her that she was writing a book on Annie Cook, and she wanted to invite Mary to tell her side of the story. Other than writing that Mary’s reaction exhibited an “all too evident pain,” Ms. Yost also characterized Mary’s immediate reaction as one of “the old paralyzing fear and pain surged upon within her.”

A gifted creative writer would’ve asked Ms. Yost to further convey for the reader Mary’s reaction to someone asking her to relive the worst moments of her life. Yet, it probably would’ve been difficult-to-impossible to do so in a paragraph, or with words written on a page. Even the greatest creative writers would’ve had a tough time conveying the extent of mental and physical torture Annie Cook inflicted on Mary over the course of sixteen years to the degree that the woman exhibited “all too evident pain” forty years later.

After Ms. Yost apologized for causing Mary such pain, she began walking back to her car. Mary recovered from the initial shock, and she asked Ms. Yost to come back. “Come in,” Mary said. “I’ll tell you what you want to know.” In the epilogue, Ms. Yost characterized Mary reliving the pain as Mary speaking “All that afternoon [reliving] all the old fear and pain and despair.” She described Mary’s “flood of words” providing “a veritable catharsis of long pent up emotions.” When Ms. Yost left, “[Mary] felt cleansed, relieved, [and] serene.” We can also only guess that Mary thought if she told this tale as she remembered it, it might help prevent others from looking “the other way and permit it to go on, as the people in this tale did.”

Before we get into the details of what Mary could remember, forty years later, how many horrors did Mary forget, and purposely forget, in her effort to try to remove these horrible stains from her mind? How many of the horrors Mary experienced were day-to-day traumas Annie committed against the young girl that weren’t noteworthy in a literary sense? How many of Mary’s memories did Ms. Yost edit down to what she considered the highlights, for lack of a better term. How many awful moments, incidents, and crimes will the reader never know that led Mary to react in such a manner at the mere mention of the name Annie Cook, forty years later? I think it’s safe to say that the true horrors this woman experienced lay not in the highlights that she relayed to Ms. Yost, but in the daily details of what Annie Cook did to these women to maintain absolute control of Mary and her mother Liz’s hearts and minds.

“We [Mary and Liz] did the daily housework, the farm chores, worked out in the fields, picked the fruit, took care of the 150 ducks, 150 geese, 400 chickens, and never less than 10 cows,” Mary testified in court, long after the worst of it was over for her. “We had to clean the manure out of the barn and clean the chicken pens.

“Whenever the work wasn’t done just when she wanted it done, or it wasn’t done just right, Anna would use the buggy whip on mom and I,” Mary furthered on the stand. “I don’t think a day passed that we didn’t get whipped. Mom and I were really scared.”

“They [Mary and Liz] were forced to clean the barn and chicken houses, and had to work from 4 A.M. to 10 P.M,” Annie’s foster son, Joe (Martin) Cook, said to confirm Mary’s testimony when he took the stand. “I saw Anna ‘sic’ the dogs onto Liz many times, and it was strictly against the rules for Liz to eat with Anna. Company got fried chicken, and we got leftovers or whatever Anna gave us.” Those two testimonies, to determine if Liz had a claim on the Cook Estate (after Annie’s death), read like victim testimony in a criminal trial. When reading through testimonies such as these, our eyes tend to glaze, as we see a recitation of facts. As Nellie Snyder Cook states in the preface of Evil Obsession the purpose of writing and reading books that deal with such sensitive subjects is to warn us to “Not look the other way and permit it to go on, as the people in this tale did.” Immersive reading of such horrors teach us how to empathize with the subjects far better than any other formats do.

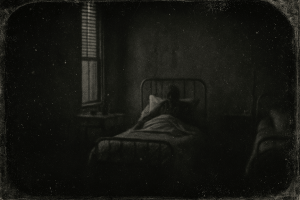

If you’ve ever done any work on a farm, you know it’s not for the faint of heart. Imagine doing it every day from 4 A.M. to 10 P.M. for sixteen years, as in the case of Mary, and forty-seven years for Liz. At the end of their eighteen-hour day, they not only were whipped with a buggy whip if the job wasn’t completed when and how Annie wanted it done, but they were also denied food at the end of the day for further punishment. Mary reports that she was denied food for three days in a row at times, and if Annie’s husband Frank hadn’t snuck her food every once in a while, when Annie wasn’t looking, she probably wouldn’t have survived. On the days when he couldn’t find a way to sneak her food, she had to do all of these chores, and wake up the next day before 4 A.M. exhausted and painfully hungry to try to do it all perfect again the next day. And if they didn’t do it according to standards, because they weren’t nourished in a manner to provide them the necessary energy to do so, Annie whipped them. (Annie’s husband Frank often treated their open wounds, when Annie wasn’t around so their wounds didn’t get infected.)

In one of Mary’s most harrowing tales, Annie introduced the then five-year-old Mary to her new life on the Cook Estate by informing her that she was to tend to livestock. When Mary informed Annie that her work shoes were still at her Aunt Nettie’s home, the home where she spent her first five years, Annie informed her that she would not be tending to livestock in her good, church shoes. Thus, she forced Mary to feed the hens and break ice for the ducks in freezing temperatures with no shoes or socks on. When the “thick coat of hoar frost” burned the five-year-old girl’s feet, she screamed out in pain. Annie instructed her to hush her bawling and hurry up. The five-year-old girl somehow managed to keep her cries of pain quieter, until they were finally done and they made their way back to the kitchen. Once there, Mary felt no pain, as her feet were now white and numb. Annie feared that she may have gone too far with the five-year-old, and she put hot water in a pan for Mary’s feet and instructed her to put her feet in it. When the color returned to her feet, Mary cried out in pain, and her Aunt Annie slapped her and told her to shut up. We readers cannot imagine how shockingly horrifying this introduction to her new life on the Cook Estate must’ve been for this little girl to learn that her aunt would force her to do work that burned her feet so badly that they were near frostbitten.

As difficult as this tale was to read, in Evil Obsession, it paled in comparison to the idea Annie came up with to remove that awful mole from Mary’s otherwise beautiful face.

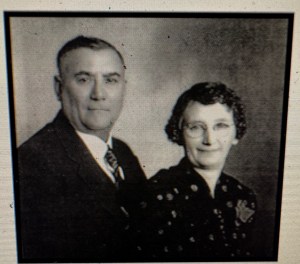

From the few pictures we have of Annie Cook, we can see that she was not an attractive woman, and we can guess that she was not an attractive young girl either. Who cares, right? What does physical appearance have to do with anything? As an unattractive person who sought power over people, Annie probably spent a lifetime seething with jealousy over the effect the beautiful can have on a room simply by walking in.

Beautiful people get us talking, whispering good things and bad. No matter how well Annie did herself up and no matter how many fancy, new dresses she wore to church, no one ever paid any attention to her. Yet, when her fellow church patrons saw Annie’s little five-year-old niece Mary walk into church, they said such wonderful things about her. They informed Annie that her young niece was a natural and unblemished beauty.

“Quite fetching,” they said. They talked about Mary’s lovely dimples, her dark hair, and her lively, sparkling eyes. Annie agreed with them that Mary had fetching qualities, but she did so with resentment. When they wouldn’t shut up about it, Annie reached a point where she couldn’t take it anymore, and she began obsessing over Mary’s lone imperfection, that mole.

“Except for that awful mole,” Annie said, after agreeing with the church ladies that Mary was a naturally beautiful, young child. “You say she’s a natural, unblemished beauty, but I can’t stop thinking about that big, ugly mole. It looks like the devil.”

“That?” the church ladies replied. “That’s nothing. It’s so little. Plus, some cultures and professions actually prize a beauty spot like that, when it’s that small.”

Annie realized that she couldn’t dissuade people from saying such things, and while she harbored deep resentment that no one ever said such things about her, she learned to accept that for what it was to some degree. When they failed to talk about her beloved daughter Clara in that manner, it frustrated Annie further.

These frustrations eventually manifested into an obsession with Mary’s mole, and Annie began ridiculing Mary for her mole relentlessly in the confines of the home the three of them shared. She did it so often that her sister Liz and Mary began to cry when Annie started in on the little girl’s one imperfection so relentlessly. After spending a lifetime with Annie, her sister Liz learned that the best way to defeat Annie’s relentlessness was just to ignore it, and she taught her daughter Mary the same. “Just ignore it,” Liz probably said at some point when she saw how Annie’s relentlessness shattered her daughter. What else could Liz do to protect her daughter?

We’ve all known bullies, and some of us have firsthand experience with their relentlessness. The one thing we all learn is that there is no handbook or standard operating procedure that will help us deal with bullies. We tried things when we were young, and we watched our peers try things, but we all reached the conclusion that nothing works. In total desperation, we reached out to our authority figures. Those of us who have experienced the desperation Liz must’ve experienced when she saw her daughter’s tears know those feelings of helplessness, but we also know that the worst thing she could’ve done was to instruct her daughter to “Just ignore it.” I don’t know if bullies sense weakness, or if they just can’t stop until someone stops them, but when I hear someone advise another to “Just ignore it” I think that’s a mistake, huge mistake! It’s a huge mistake, to my mind, because as anyone who knows a bully knows when we effectively ignore them, we deprive them of their sole source of satisfaction on the matter. Some bullies move onto other vulnerable targets, but most of them up their game.

No matter how this progression happened, Annie eventually decided to remove her five-year-old niece’s lone imperfection, saying, “That big, ugly mole looks like the devil, but Aunt Annie can take it off for you.”

To remove a mole during this era, medical practitioners with cosmetic ambitions used various, now antiquated techniques, and there was always some scarring, but their clients considered that an acceptable trade-off for removing conspicuous blemishes. Annie didn’t want to pay for all that, of course, and using such medically approved procedures wouldn’t accomplish Annie’s goal of destroying Mary’s natural and unblemished beauty.

Annie decided that the best way to remove that “awful mole” was with a coal-fired hot poker that would leave her five-year-old niece with an embarrassing and nasty scar for the rest of her life. Whether or not Annie derived satisfaction or pleasure by destroying a naturally beautiful young girl is not detailed in Evil Obsession, but it’s tough to imagine another motive for permanently scarring a five-year-old’s face. As awful as this incident sounds, the details are worse. The images that Ms. Yost provides in Evil Obsession, culled from Ms. Knox Cauffman’s retelling, left this reader with an image I might not be able to ever shake. It is, as I wrote, the most difficult story in this book to finish.

Annie decided that the best way to remove that “awful mole” was with a coal-fired hot poker that would leave her five-year-old niece with an embarrassing and nasty scar for the rest of her life. Whether or not Annie derived satisfaction or pleasure by destroying a naturally beautiful young girl is not detailed in Evil Obsession, but it’s tough to imagine another motive for permanently scarring a five-year-old’s face. As awful as this incident sounds, the details are worse. The images that Ms. Yost provides in Evil Obsession, culled from Ms. Knox Cauffman’s retelling, left this reader with an image I might not be able to ever shake. It is, as I wrote, the most difficult story in this book to finish.

The idea that this unusually awful woman got away with horrific incidents like this one and the others that would follow are another reason Evil Obsession would never reach the bestseller list. When good people read about awful people doing awful things to other people, we want retribution, especially when those usually awful things are done to an innocent, young five-year-old girl.

When readers read scenes like the near-frostbite incident and the hot poker one, we think, “That’s just too much.” Burning the feet and face of a five-year-old girl burns an image in our mind that never leaves us, and some of us fantasize about going back in time so that we can step in and stop this. We know we can’t do that, but we want to do something.

We’ve all watched moviemakers rewrite history to right a wrong in a fictional sense, and we think “YES!” when we read scenes like this one. It’s a sophomoric desire to achieve some sort of vicarious catharsis, but after I finished reading these unusually awful scenes, I imagined the five-year-old Mary fighting through the hold Annie forced her daughter Clara to hold Mary in. I had Mary grab that coal-hot poker and put it through Annie’s good eye. I also imagined Mary’s mother Liz finding a way to burst through the bedroom door at the last second to wrestle around on the floor with Annie, burning herself and Annie on the hot poker, but sparing Mary that horrific moment in her young, naive, and unblemished years. “We could rewrite scenes like this one and add a ‘based on a true story’ subtitle to the book,” I would submit to Ms. Yost if I were given the chance to ghost write her book with her. “We cannot leave this scene as is, I can’t anyway, because I won’t be able to sleep again, thinking I should’ve done something. Someone should’ve done something, our readers will think, and they’ll throw the book across the room, and they won’t recommend it to anyone, saying, “It’s a beautiful, little five-year-old girl we’re talking about.”

“It’s the truth though,” Ms. Yost would argue. “And the sad truth is that some of the times the most awful people in history got away with everything. One of the goals of any author writing a long-form book of true horror is to procure intimate levels of sympathy and empathy in the reader, so that if they witness similar incidents of true horror in their life, they might do something or say something to prevent the escalation that follows. If we fictionalize to add some sort of fictional retribution, we remove ingrained images that the truth could foster.”

Mary’s Independence Day

The criminal acts Annie Cook allegedly committed, commissioned, and took part in were not of cinematic quality. Starving patients to death, leaving them in an abandoned wagon box to either bake in the Sun or starve, and mentally and physically scarring a five-year-old for life are not horrific events that would excite an audience looking for a “cool” bad guy. These are relatively insignificant incidents against the insignificant that stick in the mind for decades, because of our almost ingrained and reflexive desire to protect the insignificant. My guess is that the relatively minor incidents Mary could remember forty years later don’t scratch the surface of the mental and physical torture Mary endured. My guess is its 1/100ths of the story that ruined that good woman’s life.

As awful as Marys’ tales in this book are, they do lead to the one redeeming tale in Evil Obsession. It occurs soon after Mary refuses to become one of Annie’s prostitutes. “I’ll die before I do that,” she said when Annie put forth the notion when she believed Mary was old enough to become one of Annie’s entertainers. Mary’s reaction makes clear that Annie’s command pushed her beyond the terror she always had of the woman. When Annie threatened to test Mary’s resolve by ending her life with her buggy whip, Mary screamed, “Never!” After a prolonged stand down, Annie tossed her whip aside and grabbed a big butcher knife that her husband Frank always kept as sharp as possible. Holding the knife like a spear, Annie ran at the screaming girl. Mary jumped to the side at the very last moment and caught the knife in the hip as opposed Annie’s more fatal target, the stomach, and Mary ran from the Cook Estate when Annie prepared to strike again.

After Mary managed to escape the confines of the Cook Estate and into North Platte, she ran to the safety of a new sheriff, who was not under Annie Cook’s thumb. The new sheriff wouldn’t return Mary to Annie in the manner the old one would, as he stated that she was now of age, and she didn’t have to return to the Cook Estate if she didn’t want to do so.

This was the third time Mary managed to run away from the Cook estate, and this reader slowly worked his way through the next few chapters waiting for Annie to eventually find a way to force town officials to bring her back. Annie did try, numerous times, but she failed. Mary managed to secure her own freedom, and she went onto live a decent, though thoroughly damaged life.

I hate to confess this, but when I purchase a book about unusually awful people, I usually find the redemptive stories of those who managed to escape and live a relatively normal life a little anti-climactic. Most authors detail the relatively boring but free life these victims of the tale enjoyed. Ms. Yost provides those extensive details of Mary’s new, independent life, but no matter how mundane and relatively boring those details were, I found myself cheering every detail of that woman’s newfound independence. Mary worked in a hotel, cleaning rooms for the woman who housed her, and she worked on a father-in-law’s farm after a failed marriage. She then did some odd jobs, like cleaning work, to help pay the bills. Again, I don’t know if other readers will savor these relatively insignificant details, but I cheered on every word, because the mentally and physically tortured Mary Knox did them as a free woman. As a free woman, Mary tried secure the freedom of her mother, Liz, for twenty-eight years, she tried, and she lived within ten miles of her mother, but Liz would remain under Annie’s control until the day Annie died.