“Did you know that your friend’s dad is an infidel?” my friend’s mom whisper-shouted at me when she opened the door. She had her angry face on. Mrs. Finnegan was not quite right in her normal state, but when I saw that look on her face, I knew something was brewing in the Finnegan household. I could’ve just walked away, I see that now, but I was a good kid. When you’re a good kid, a vital definition of your being comes from other kid’s parents. I was so far down this road that the thought of walking away didn’t even cross my mind. I just considered it my lot in life to endure whatever was going on beyond that door. Even though her angry expression put me on edge, I was accustomed to the greeting. Mrs. Finnegan greeted me this way whenever she had a topic that we needed to discuss before she would permit me to hang out with her son. I called it her headline hello.

“Hey, it’s mister cigarette smoker!” she said to introduce me to the Finnegan family discussion of another day, one that involved regarding my smoking habits. “It’s the heavy metal dude!” she said to introduce me to another discussion we were going to have about my decision to wear a denim jacket, a t-shirt of whatever band I was listening to at the time, and jeans. She called my ensemble ‘the heavy metal dude gear’ in that discussion. I was fair game for these family discussions, Mrs. Finnegan said, because I had such a huge influence on her beloved son, and the state of my home required that I receive further guidance.

“Hey, it’s mister cigarette smoker!” she said to introduce me to the Finnegan family discussion of another day, one that involved regarding my smoking habits. “It’s the heavy metal dude!” she said to introduce me to another discussion we were going to have about my decision to wear a denim jacket, a t-shirt of whatever band I was listening to at the time, and jeans. She called my ensemble ‘the heavy metal dude gear’ in that discussion. I was fair game for these family discussions, Mrs. Finnegan said, because I had such a huge influence on her beloved son, and the state of my home required that I receive further guidance.

The “Your friend’s dad is an infidel” greeting informed me that the Finnegan family discussion of the day would involve her husband’s recent business trip to Las Vegas in which “he happened to get himself some [girl]”. I substitute the word ‘girl’ here for your reading pleasure, in place of the more provocative word that Mrs. Finnegan used to describe the other party in Greg Finnegan’s act of infidelity.

Mrs. Finnegan was a religious woman who rarely ever used profanity or vulgarity. She reserved those words for moments when she needed to severely wound the subject of her scorn, with a ‘Look what you’ve made me do,’ plea in her voice to further subject the subject of her scorn to greater shame, ‘I’m using profanity now.’

I would hear Francis Finnegan use vulgar words on this afternoon, but it wasn’t as shocking to me as hearing that initial misuse of the word infidel. As a self-described word nerd, Mrs. Finnegan prided herself on proper word usage, in even the most casual conversations. I was into it too. I was so into using proper words that she informed me on another occasion, half-joking, that I was her apprentice. She enjoyed teaching me, and I was her eager student. In the beginning, I viewed her assessment of our roles in that light. As the years went by, however, I began to believe she said that to relieve whatever guilt she may have felt for correcting every other word that came out of my mouth. It could prove exhausting at times. There were times when I was almost afraid to open my mouth around her, lest she correct me, but I did enjoy our respective roles in this relationship.

I figured that the emotional turmoil of this moment might have caused the faux pas, but her diction was so proper and refined that I didn’t consider her capable of such a slip. Even during the most tumultuous Finnegan family discussions, the woman managed to mind her rules of usage well. Thus, when she made the error of attributing the word infidel to her husband’s act of infidelity, I assumed she intended to pique the interest of the listener in the manner her sparse use of profanity and vulgarity could. Either that or she was providing herself a respite from the rules to creatively conflate the incorrect use of the word, and the correct one, with an implicit suggestion that not only had her husband violated his vows to her, but his vows to God.

My friend James was seated on the couch, next to his father, when I entered the Finnegan home. The two of them were a portrait of shame. They sat in the manner a Beagle sits in the corner of the room after making a mess on the carpet.

My friend James was seated on the couch, next to his father, when I entered the Finnegan home. The two of them were a portrait of shame. They sat in the manner a Beagle sits in the corner of the room after making a mess on the carpet.

James mouthed a quick ‘Hi!’ to me, as I walked by him, and he pumped his head up to accentuate that greeting. He then resumed the shamed position of looking down at the carpet.

“Mr. Finnegan decided to go out to Las Vegas and get him some [girl]!” Mrs. Finnegan said to open the proceedings when I entered the living room. I did not have enough time to sit when she said that. When I did, I sat as slow as the tension in the room allowed. “Tell him Greg,” she added.

“France, I don’t think we should be airing our dirty laundry in front of outsiders,” Mr. Finnegan complained. The idea that he had been crying was obvious. His eyes were rimmed red and moist. He did not look up at Francis, or me, with his complaint. He, like James, remained fixated on the carpet.

France was the name Mrs. Finnegan grew up with, and she hated it. Only her immediate family members addressed her with such familiarity. She had very few adult friends, but to those people she was Frances. To everyone else, she was Mrs. Finnegan. She may have permitted others to call her less formal names, but I never heard it. Mrs. Finnegan was not one to permit informalities.

“NO!” Mrs. Finnegan yelled at her husband. That yell was so forceful that had the room contained an actual Beagle, it would have scampered from it, regardless if it were the subject of her scorn. “No, he has to learn,” she said pointing at me, while looking at her husband. “Just like your son needs to learn, just like every man needs to learn the evil of their ways.”

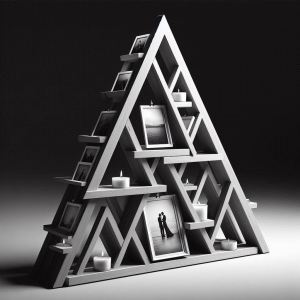

A visual display followed that verbal one. It was carried into the living room by the Finnegan’s dutiful daughter. The daughter appeared as removed from this family discussion as she had the prior ones. She was more of an observer of the goings on in the Finnegan home than a participant, in my brief experiences with Finnegan family discussions. She rarely offered an opinion, unless it backed up her mother’s assessments and characterizations, and she was never the subject of her mother’s scorn. She was the dutiful daughter, and she walked into the room, carrying the display, in that vein. She carefully positioned it on the living room table and pulled out its legs, so it could stand. She then lit all of the candles in the display and sat next to her mother when it was complete.

Mrs. Finnegan allowed the display of Greg Finnegan’s shame to rest on the living room table for a moment without comment. The display was a multi-tiered, wood framed, structure with open compartments that allowed for wallet-sized photos. The structure of the frame was a triangle, but anyone who looked around the Finnegan family home could see evidence of Mrs. Finnegan’s fondness for pyramids. Greg Finnegan purchased the triangle to feed into her obsession, but it did not have the full dimensions of a pyramid. When the daughter pulled its legs out, however, the frame rested at an angle. At that angle, the frame took on the appearance of one-fourths of a pyramid.

Mrs. Finnegan allowed the display of Greg Finnegan’s shame to rest on the living room table for a moment without comment. The display was a multi-tiered, wood framed, structure with open compartments that allowed for wallet-sized photos. The structure of the frame was a triangle, but anyone who looked around the Finnegan family home could see evidence of Mrs. Finnegan’s fondness for pyramids. Greg Finnegan purchased the triangle to feed into her obsession, but it did not have the full dimensions of a pyramid. When the daughter pulled its legs out, however, the frame rested at an angle. At that angle, the frame took on the appearance of one-fourths of a pyramid.

Before this discussion began, Mrs. Finnegan somehow managed to secure enough photos of the “harlot, slut, home wrecker” to fill each of the open compartments in the pyramid with unique photos of woman. Each photo had a small votive candle before it to give the shrine of Greg Finnegan’s shame an almost holy vibe.

“It’s the pyramid of shame,” Mrs. Finnegan informed me with a confrontational smile. “It was Greg’s gift to me on my birthday. Isn’t it lovely? I’m thinking of placing it in our bedroom. I’m thinking of placing it in a just such a position that if Greg is ever forced to sex me again-” Except she did not say sex. She uttered the word, the big one, the queen mother of dirty words, the “F-dash-dash-dash” word. “-he can look at those pictures while he’s [sexing] me. Do you think that will help your performance honey?” she asked her husband.

As we sat through that uncomfortable comment, the question of how far Mrs. Finnegan might go with her characterizations of her husband’s weekend was mercifully interrupted by a knock at the door. For obvious reasons, we did not see an individual approach the door, so the knock startled us. The construction of the Finnegan duplex was such that when the drapes were open the inhabitants could see the knocker if they were facing in that direction, but we were all looking at the carpet before us. The knocker was Andy, the third participant in the adventure James and I planned for the evening.

“Welcome to the home of Greg Finnegan, adulterer and infidel,” Mrs. Finnegan said after leaping to her feet to beat everyone to the door. No one was racing her to the door. We were scared and shamed into staring at the carpet. “Come on in,” she said stepping back to allow Andy’s entrance.

Andy turned around, walked back down the steps, got in his car, and drove away. Just like that, Andy escaped what I felt compelled to endure. Andy didn’t respond to Mrs. Finnegan’s greeting in anyway. He didn’t go out of his way to show any signs of respect or disrespect. He just turned and left.

I didn’t know we could do that, I thought. I turned to watch him walk away, and I turned even more to see him step off the Finnegan patio. I realized he was actually leaving, and my mouth fell open. I didn’t know we could do that.

Andy left, because he knew what Mrs. Finnegan’s headline hellos entailed. He knew what he was in for, and I did too. To my mind, his departure was not only inexplicably bold, it was so unprecedented that it set a precedent for me. I didn’t know we could do that.

“How could you do that?” I asked him later.

“I didn’t want to go through all that all over again,” he said.

“Well, of course,” I said. “Who would?”

Andy further explained his reaction, but the gist of it was that he just didn’t want to have to sit through another Finnegan family discussion. His impulsive reaction was so simple that if he laid it all out before me, I would’ve countered that he never would’ve been able to pull it off. I’m sure he would’ve asked why, and I don’t know what I would’ve said, but it would’ve involved the inherent respect and fear we have of other people’s parents. Andy and I were good kids, and good kids consider it a testament to their character to maintain model status around other people’s parents, so I didn’t think Andy would be able to be so bold. When Andy did it, and Mrs. Finnegan did nothing more than close the door, I realized that I would have to do a much better job of considering my options in life.

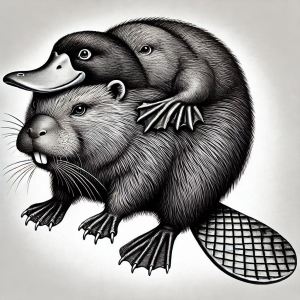

After Andy left and Mrs. Finnegan sat back down, she encouraged Mr. Finnegan to begin the confessional phase of the Finnegan family discussion, a phase that required Mr. Finnegan to provide explicit details of what he did, I wasn’t there to hear it. I was imagining that Andy impulsive reaction to Mrs. Finnegan’s headline hello so emboldened me that I just stood up and followed him to his car. Just like that. Just like he did. I imagined the two of us driving away, laughing at the lunatics we left behind. I imagined calling the Finnegans platypus people at one point in our round of jokes, and how that might end Andy’s laughter, until I said:

“What is a platypus, but an animal that defies categorization. One study informs the world of science that they should fall into a specific category, until more exploration reveals that the duck-billed mammal does something to contradict all of their previous assessments. Comprehensive study of the animal creates more questions than answers, until even the most seasoned naturalist throws their hands up in the air in futility. “Experts in psychology might think they have a decent hold on human classifications,” I would add,“but imagine what one day in the Finnegan family home could do to them.

“At its introduction, naturalists considered the platypus another well-played hoax on the naturalist community, I would add. “I say another well-played hoax because it happened. Some enterprising naturalists stitched together body parts of various parts of dead animals to lead the scientific community to believe that the hoaxer discovered an entirely new species. Thus, when someone introduced the platypus, the scientists who received it believed it was but another elaborate hoax of taxidermy.

“At its introduction, naturalists considered the platypus another well-played hoax on the naturalist community, I would add. “I say another well-played hoax because it happened. Some enterprising naturalists stitched together body parts of various parts of dead animals to lead the scientific community to believe that the hoaxer discovered an entirely new species. Thus, when someone introduced the platypus, the scientists who received it believed it was but another elaborate hoax of taxidermy.

“Those who guarded themselves against falling for future hoaxes, even had a tough time believing the platypus was an actual species when they saw one live,” I would add.

Even after this afternoon concluded, and I had all the sordid details of this Finnegan Family as Platypus People story to tell, I wondered if anyone would believe me. My penchant for stitching facts together with exaggerated details to try to weave them together for an exceptional story might come back to haunt me. They might not even believe the story if Andy stuck around to corroborate the details of it, and they might not even believe it if they saw it live, I realized while Mr. Finnegan continued to offer me explicit details of his weekend. My audience might think they’re the subjects of an elaborate hoax.

“He already confessed all of this to his children,” Mrs. Finnegan said to interrupt Mr. Finnegan’s confession, “and he will be offering detailed confessions to the mailman, a traveling salesman, and whomever happens to darken our door this evening.”

After Mr. Finnegan’s continued confession failed to meet Mrs. Finnegan’s requirements, she interrupted him again to ask a series of questions that further explored the humiliating details of Mr. Finnegan’s weekend, details he would not reveal without prompting. When that finally concluded, she forced us to acknowledge the primary reason the Finnegans married in the first place.

“No one would play with Mr. Finnegan’s [reproductive organ],” she said, except she didn’t say reproductive organ.

“He was lonely,” she said with tones of derision. “Mr. eighty dollars an hour consultant fee, and Mr. professional student with eight degrees would be nothing without me, because he was nothing when he met me. He was a lonely, little man who had nothing to do but play with, except his little computer products, designs, and his little reproductive organ when no one else would.”

“That’s enough France,” Greg said standing. He stood to bolster his claim that he’d had enough, and that he was prepared to leave, but he couldn’t and Mrs. Finnegan knew that.

“Do you play with your reproductive organ?” Mrs. Finnegan asked me, undeterred by Greg’s pleas. “Do you masturbate? Because that’s where it all starts. It all starts with young men, and their pornographic material, imagining that someday someone will want to come along and want to play with it.”

I had no idea how this family discussion would play out, of course, but I could see Mrs. Finnegan’s confrontational demeanor building. She was a confrontational person, and I never saw her attempt to restrain herself, but this display of resentment and hostility was unprecedented for her, as far as I was concerned. She was all but spitting these questions out between bared teeth, and her nostrils flared in a manner of disgust that suggested her hostility was directed at me.

“You think it’s about love?” she asked me, aghast at a comment I never made. She had a huge smile on her face when she asked that question, and that smile might have been more alarming than the way she asked all those previous embarrassing questions. Seeing that smile surround those angry teeth led me to wonder if she was losing control of her facilities.

“You think every couple has a story of dating, that hallowed first kiss, and love?” she continued. “Go watch a gawdamned love conquers all movie if you want all that and once it’s over, you come to Mrs. Finnegan with your questions, and I’ll introduce you to some reality. I’ll tell you tales of young men, grown men, who marry because they’re desperate to find someone to play with their reproductive organ. Isn’t that right Mr. Finnegan?” she called after Mr. Finnegan, as he finally mustered up the courage to begin walking away from her. When he wouldn’t answer, or even turn to acknowledge her question, Mrs. Finnegan watched him leave, she looked at me, and then she tore off after him.

Mrs. Finnegan was a deliberate woman who appeared to consider her motions before moving as carefully as the words she used to express herself, so to see this otherwise sedate woman move so quickly was a little startling, troubling, and in retrospect foreboding.

Pushing a grown man down a flight of stairs is not the feat of strength that some might consider it. We didn’t see it, but we figured that he must have been off balance when she did it, resulting from his refusal to turn and face her in his path to the basement. She was screaming things at him from behind, and her intensity grew with each scream until we could no longer understand the words coming out of her mouth. Mr. Finnegan continued to refuse to turn around and face her, but he should’ve suspected that his wife’s intensity would lead to a conclusion against which he should guard himself. Thus, when she pushed him, he was in no position to defend himself or lessen the impact of falling down a flight of about twenty steps.

When we ran to the top of the stairs –after the sounds of him hitting the stairs shook the house in such a manner that all three of us instinctually put a hand on the armrests of the furniture we sat in to brace ourselves– we witnessed her haul her six-foot-five, two-hundred-pound husband upstairs by his hair, one-handed.”

Mrs. Finnegan’s final scream, that which proceeded her pushing her husband down the stairs, led us to believe that whatever frayed vestige of sanity she clung to for much of her life just snapped. I couldn’t understand what Mrs. Finnegan screamed as she pulled him up the stairs by his hair, but I wasn’t sure if that was because the screams of her children, and her husband, drowned out those shrieks.

“France!” I heard Greg scream in pain. “France, for God’s sakes!” he screamed repeatedly.

When I saw Mrs. Finnegan’s contorted facial expression, it transfixed me. In their attempts to either help her, or break her hold on Mr. Finnegan’s hair, her children blocked most of my view of her face. I bobbed and weaved to see more. I didn’t know why my need to see her face drove me to such embarrassing lengths, but I all but shouted at those obstructing my view of it to move out of the way.

I’ve witnessed rage a couple of times, prior to Mrs. Finnegan’s, but I couldn’t remember seeing it so vacant before. This almost unconscious display of rage was one that those who aren’t employed in various levels of civil service might see once in a lifetime.

Her body blocked any view we might have had of Mr. Finnegan, but I assumed that he was back stepping the stairs to relieve some of the pain of having his hair pulled in such a manner. We could also guess he was putting his hand on the handrail in a manner that assisted her in pulling him up. Regardless the details of the moment, it was still an impressive display of strength fueled by a scary visage of rage.

She was in such a state that when she was finally atop the stairs, standing in the kitchen with her children trying to calm her, she couldn’t form intelligible words. Her lips were moving but no sound was coming out, and when that initial brief spell ended, the self-described word nerd could only manage gibberish, the same gibberish that proceeded her pushing her husband down the stairs, and all moments between. She later suggested that that gibberish resulted from being overcome by spirits. Once she escaped that state, she stated that the gibberish we all heard was her speaking in tongues. She believed that divine intervention prevented her from further harming her husband, in the manner divine intervention once prevented Abraham from harming his son Isaac in the Biblical narrative. I believed it too, in the heat of the moment, but I would later learn that I just witnessed my first psychotic episode.

She was in such a state that when she was finally atop the stairs, standing in the kitchen with her children trying to calm her, she couldn’t form intelligible words. Her lips were moving but no sound was coming out, and when that initial brief spell ended, the self-described word nerd could only manage gibberish, the same gibberish that proceeded her pushing her husband down the stairs, and all moments between. She later suggested that that gibberish resulted from being overcome by spirits. Once she escaped that state, she stated that the gibberish we all heard was her speaking in tongues. She believed that divine intervention prevented her from further harming her husband, in the manner divine intervention once prevented Abraham from harming his son Isaac in the Biblical narrative. I believed it too, in the heat of the moment, but I would later learn that I just witnessed my first psychotic episode.

I don’t know what happened in the aftermath of this incident, as I never entered their home again. I do know that the Finnegan marriage survived it, and I’m sure that Mrs. Finnegan still believes that divine intervention played a role. I’m also sure that if anyone doubted her assessment, they would be greeted at the door with a “Welcome to the home of the divine intervention!” headline hello to introduce them to that Finnegan family discussion of the day. If those future visitors were to ask me for advice on this matter, I would advise them to consider their options before entering.