Evel Knievel was so cool that he could wear a cape, and no one would question why a grow man was wearing a cape. He was so cool that it just seemed right on him. There was a time when Evel Knievel ruled the world, ok maybe not the world, but he definitely ruled the United States for what some say was about nine years, between the late 60s to mid-70s. He had his own toys, his likeness was on lunch boxes, T-shirts, and I even saw an Evel Knievel pinball machine one time in an arcade. I couldn’t play the pinball machine, of course, because the wait time was far too long for me, but it was fun to watch it. We all had our favorite comic book heroes, athletes, and other assorted entertainers, but there was only one “real” man who could wear a cape in public without anyone asking, “What the hell is going on here?”

Evel Knievel could jump anything and everything we could dream up and never fail. All right, he failed … a lot, but we didn’t care about all that back then. We wanted to see him do what he did “better than anyone else ever has or ever will”, and we pretended to be him when riding our bikes. Robert Craig Knievel probably wouldn’t have listed this in the greatest of achievements in his life, but it was huge in our world. The list of characters we pretended to be was about as exclusive as lists can be. We bestowed this honor on The Six-Million Dollar Man, members of the rock group KISS, and various other mythological creatures we call superheroes, but Evel was a superhero to us.

Thus, it would’ve stunned us to learn that when the history of motorcycle stuntmen was eventually written, Evel Knievel wasn’t even the best motorcycle stuntman in his own family. His son Robbie Knievel proved smarter, more technical, and more prolific than his celebrated father. (Evel committed to 75 ramp-to-ramp jumps while his son engaged in 340, nearly five times more than his beloved father.) Robbie, it could be argued, even created a better name Kaptain Knievel. How cool is that? The name Kaptain Knievel rolls off the tongue with such ease that I’m surprised Andrew Wood didn’t write a Kaptain Knievel song for his band Mother Love Bone. Kaptain Knievel could’ve and probably should’ve been more famous than his father, Evel Knievel, so why wasn’t he?

Timing: Evel Caught Lightning in a Bottle

I was not a viable lifeform when Elvis rocked our world, and I was not here for Beatlemania, but I saw, firsthand, the hysteria that was Evel Knievel. The guy hit the scene like a comet in the 70s, a red-white-and-blue blur of bravado that turned him into a myth before I even learned how to tie my own shoes. When my friends and I were old enough to hero-worship, we had Evel’s iconic imagery all over our world, from posters on our wall, lunchboxes we took to school, and T-Shirts on our torso. Evel just owned a once-in-a-lifetime sweet spot in time that no one, not even his own son, could duplicate, no matter how much higher or farther he flew. Before he died, this son, Robbie Knievel, Kaptain Knievel, ended up not only continuing the Knievel legacy, he topped it by all measures, but he could never match the fever-pitch frenzy, and the hysteria, that surrounded Evel Knievel. No one could. It was a very special window in time, and unlike some icons who shied away from the spotlight with something called humility, Evel reveled in his moment in the sun.

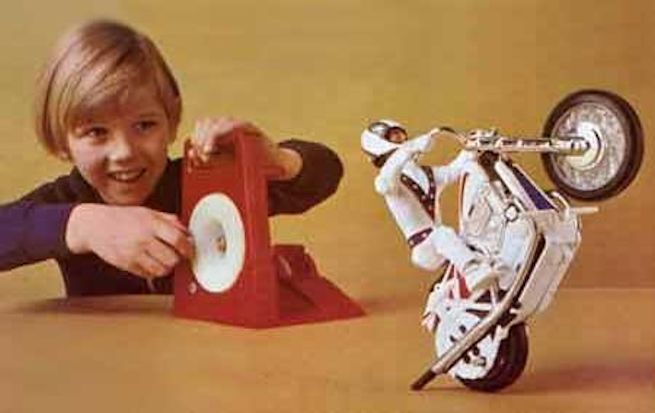

It was not mandatory that every kid in this era have an Evel action-figure, but those who didn’t received that “You don’t know what you’re missing” look, even from the nice kids. Mr. Rogers, from Mister Rogers Neighborhood, would never allow his network to commodify his product in this manner, because he didn’t want kids who couldn’t afford those products to feel ostracized. Evel had no such concerns, as his spangled merch flooded every store in the 70s.

I had three different Evel Knievel action-figures–same figure, different outfits—I didn’t care. I had to have them all. Then, we found out that the Evel Empire produced a windup, energizer accessory. If you were a kid during this era, you probably still owe your parents an apology for all the whining and badgering you did as Christmas day approached, because you were probably as awful to them as I was to mine. When Santa Claus ended up fulfilling my only wish, I wound ‘er up and let ‘er go, and when I was done, I was pretty sure I wouldn’t experience a level of euphoria equal to, or greater than that moment if I lived to be 100-years-old. Decades later, I tried passing those feelings of euphoria onto my nephew with an exact replica of this Evel figure and its windup energizer accessory, he broke it within a week. Weeks after that Christmas, I found this toy I once cherished on the top shelf of toys of his closet to gather dust with the toys he would never play with again. The idea that my nephew had no regard for this toy stunned me. I knew he never heard of Evel Knievel, but I thought it was a standalone, great toy. I was wrong. The euphoria I experienced playing with this toy, at his age, was obviously based on the mythology, iconography, and the hype and hysteria of all things Evel in the 70s.

The Media: Evel Owned the Airwaves

There was a time when one individual could rule the airwaves, and Evel Knievel did. It was so far back that it almost seems quaint now before cable, YouTube, VCRs, DVRs, and the internet or streaming services. There were only three channels, and they didn’t repeat broadcasts, or if they did, we usually had to wait months for the rerun. If we missed one of his appearances, pre-jump interviews, and the events themselves, we were just out. “You missed it?” our friends asked. “How could you just miss it? I was counting the days till it happened.”

“I forgot. I was out playing or something, and I just, just forgot,” I said to my never-ending shame. It was one of those situations where our friends could recount what happened for us, but it wasn’t the same, and we had this idea that this might mark us for the rest of our lives.

Robbie, bless him, hit his stride when cable and the internet fractured the game. Sure, he got some TV love—his Grand Canyon leap was aired live after all—but Evel’s regular-network spectacles had a bigger and rarer feel that had that must-see-TV feel, long before the networks coined the phrase. Robbie could share his feats online, but that magic of “counting the days till it happened” were long gone.

Evel Knievel Was Larger Than Life

Back before the internet and 24-hour news shows, we didn’t know everything, all of the time. We didn’t know the negatives about our heroes. We had our naysayers of course, but we could dismiss their ideas as speculative, because they didn’t really know what they were talking about either. We couldn’t pull up a device and search for all nuggets on Evel Knievel to find everything we wanted to know about him. If I ran into him at the supermarket, I wouldn’t have known it was him, because I didn’t even know what he looked like. I figured he probably looked as good as Superman with Batman’s aura of cool. We filled in the blanks of what we didn’t know with what we wanted to think, and we decided to make him god-like. Kaptain Robbie probably ended up pulling off more dangerous stunts, and if we gauged them by qualitative and quantifiable measures, he was probably the better of the two motorcycle daredevils, but Evel was there first. He also pioneered the iconic image of guts and glory in a way that led to a cultural impact that penetrated the zeitgeist in a way no one, not even his son, could.

Evel was also a Mess

I was a kid during Evel Knievel’s prime, so I didn’t know all the ins and outs of what Evel did, and I was too young to analyze why he had such historical allure. He wasn’t really human to me. He was an action-figure to me, a symbol for everything I wanted to be, but he was no more real or unreal than Batman—an action figure, literally and figuratively. Yet, this obviously wasn’t reason he was so famous among adults. Why did they love him to the point that every source of media had to have some attachment to him in some way if they hoped to compete in the era’s landscape? He crashed. A lot. “You know what I was really good at,” Evel told his cousin, and U.S. Congressman, Pat Williams. “You know what I was bad at was the landing. It was the bad landings. That’s what brought the crowds out. Nobody wants to see me die, but they don’t want to miss it when I do.”

As evidence of that, Evel Knievel’s most iconic video is that of his failed jump at Caesar’s Palace. After he narrowly missed hitting the landing ramp square, he bounced up and over his bike. When he hit his head, he appeared to narrowly avoid life-altering impact, but when his lower back and hindquarters slammed into the ground, the audience at-home could almost feel the hollow thud that must’ve screamed in Evel’s ears. When he rolled about four times, it didn’t look real. He looked like a ragdoll or one of those crash test dummies that we watch react to impact with an emotional distance, because they’re not alive. Anyone who has ever crashed on a bike, in a car, or on a bigwheel knows some small, not even worth discussing level of comparable pain that teaches us the golden rule of crashing: If you’re going to crash, try your best to avoid landing on concrete, because it hurts like the dickens.

Why did adults of this era watch? Why do non-fans watch NASCAR, hockey, and why do we slowdown for a wreck on the interstate. Adults presumably turned up at the shows and tuned into the broadcasts that carried these performances, because they wanted to be there if someone was going to die that day.

Whereas the son, Kaptain Knievel, achieved twenty different records, Evel racked up twenty major crashes, and his own Guinness Book of World Records’ record 433 broken bones. 433! Yes, Biology enthusiasts, we only have 206 bones in our body, and no he didn’t have more than double the number of bones the rest of us have. If you’re going to attempt to break Evel’s current record, you’re probably going to have to break the same bones multiple times. Kaptain Knievel decided he didn’t want to go the course of his father, so he chose a Honda CR500, a much lighter bike than Evel’s Harley-Davidson XR-750, and Kaptain Robbie analyzed his jumps and made sure he would succeed. He did succeed far more often than his famous father, but the adult audience probably grew so accustomed to his success that they kind of got used to it in a way that bored them a little.

“I’m not going to watch,” my aunt said before one of the airings of Evel’s jumps, “because I’m not going to contribute to that man’s desire to kill himself, because he will die. You know that don’t you? That fool is going to get himself killed.”

My aunt was right, of course, as Evel wasn’t very good at what he did. Kaptain Knievel had some crashes too, but they paled in comparison to the severity of Evel’s. When Evel crashed, we felt bad for him, we thought of his family and other loved ones, and some of us even cried a little. We did it, because we cared, and we enjoyed caring, because we didn’t want to see this beloved man get hurt again. Robbie never built that reservoir of love and concern, because he rarely failed, and when he did, he didn’t get hurt as severely, and we viewed him as nothing more than a guy who used a motorcycle to jump over stuff.

The most memorable jump Evel Knievel performed, for me, was the January 31, 1977 jump at the Chicago International Ampitheatre. This scheduled event suggested that Evel was going to jump over a number of sharks, SHARKS! This event just happened to coincide with the aftermath of the first true summer blockbuster, Jaws. Jaws was a movie so horrific and scary that no one I knew was allowed to see it, but as you can guess that verboten nature led us to talk about it endlessly. We all knew someone who knew someone who saw it, and we recounted for our friends what actually happened in that movie. Thus, when we learned that our superhero was going to test the meddle of the world’s most fearsome maneater, we kind of worried:

“What if he misses?” we asked one another, in the midst of the hysteria. “What if a shark jumps out of the water, as he’s flying overhead? They do that. No seriously, I’ve heard that they do that.” None of us knew that sharks are actually relatively cautious predators, and the reason their predatory behavior involves them circling unknown prey is that they’re trying to determine if they’re going to get hurt in the process. They know that even a small, relatively innocuous injury can damage their predatory skills and could lead to their premature death. If Evel splashed into the tank, in other words, the sharks that weren’t hit on impact, probably would’ve swam as far away from the point of impact as possible. We didn’t know any of that. We thought they were the impulsive killing machines depicted in Jaws. I later learned Evel’s jump ended in disaster during a rehearsal, and he retired from major jumps shortly afterward, but none of that mattered to me as I was all hyped up on everything Evel.

We loved to ride bikes in the wayback when kids did things outside, and every kid I knew pretended to be Evel Knievel for just a moment when we took rocks and put plywood on them and “jumped” from one board to another. When we did this often enough, even in our Evel Knievel mindsets, it could get a little boring after a while. To try to match the intensity of our hero, we did everything we could to make our jump more dangerous. We increased the angle of the board, had our friends lay between the two boards, and any and every stupid thing we could think up to make it a little more dangerous. We wanted someone, somewhere to say, “You are crazy!” No one ever said that in an advisory manner, in my memory, it was always said with a tinge of excitement, as in ‘He’s crazy, but I think he’s going to do it.’ I still remember the time I broke Steve’s record on the block for longest jump, but even though it ended with a me-bike-me-bike roll up crash, I still beat it. Was it worth it, if you asked short-term me, I probably would’ve said no, as there was a lot of memorable pain, but when the theys on the block were still talking about it, months later, it felt worth it. They talked about the painful crash of course, and they laughed when they did, but they always mentioned that it set the record for the block.

We unwittingly answered the question why Evel Knievel was more popular and still is more famous than his son Robbie. Evel was either so stubborn, or so crazy, that he didn’t want to do things the way they should’ve been done. He performed with a “my way or the highway” that usually led to him waking up in a hospital. Evel Knievel did succeed on occasion, and we shouldn’t forget that, but when he did, it was almost a relief to see that he didn’t get hurt in the process. Robbie Knievel was so good at what he did, presumably learning from his father’s mistakes, that when he completed a jump, it eventually became less of a daredevil feat and more of a guy jumping over stuff with a motorized vehicle. There was no drama to it, and it lacked the “Is he going to die today?” had-to-be-there-if-he-did status that his father’s jumps did.