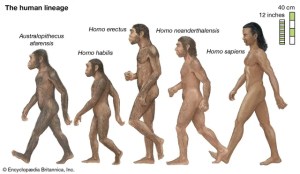

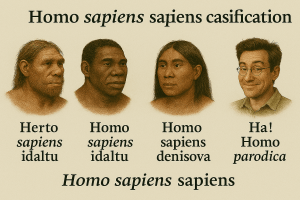

Taxonomists and biological anthropologists classify modern humans as the Homo sapiens sapiens species. No, that is not a typo. The reason for the double-word is that we are a subspecies of the Homo sapiens species. Taxonomists and biological anthropologists created this distinction to separate Homo sapiens sapiens species from the Homo sapiens neanderthalensis, or Neanderthals, the Homo sapiens idaltu, or Herto man, and the debatable inclusion of the Homo sapiens denisova, or Dragon man. We’re all homos, in other words, under the genus Homo, and the biological anthropologists break us down after that.

Our Homo sapiens sapiens subspecies is characterized by advanced cognitive abilities, language, and complex social structures. We’re the most complex subspecies in this regard, but if aliens from another planet were to meet us, greet us, and play in all our reindeer games, they probably wouldn’t agree that we all belong in the same categorization.

Our Homo sapiens sapiens subspecies is characterized by advanced cognitive abilities, language, and complex social structures. We’re the most complex subspecies in this regard, but if aliens from another planet were to meet us, greet us, and play in all our reindeer games, they probably wouldn’t agree that we all belong in the same categorization.

When we talk about Alien Life Forms (ALFs) here, we’re talking about Spock, S’Chn T’Gai Spock from the original Star Trek. Spock was half-human, half Vulcan, but we’re going to characterize our ALF as a full-on Vulcan, a full-on reason and rational thinking Vulcan with no empathetic or sympathetic emotions. In this ALF’s After Earth report home, it would write, “Even Earth’s scientists refrain from proper delineations in their Homo sapiens subspecies, because the scientific community thinks that a proper breakdown of various individuals in their subspecies might hurt feelings, but there are clear delineations. Some Homo sapiens sapiens have not fully evolved to the point that they belong to that species. Others have.”

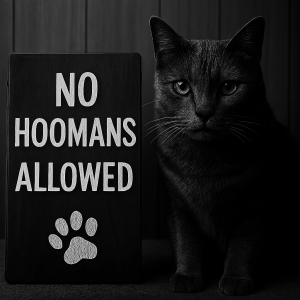

If we never meet Spock-like ALF, or fail to prove they exist, we’ll never be able to verify this characterization. Thus, we will have to turn to the closest thing we have to an Alien Life Form in our universe, one with intimate knowledge of the Homo sapiens sapiens that is dispassionate enough to provide objective analysis. I would nominate the cat. Anyone who has owned a cat knows that we share an off again relationship with them. The cats definition of our relationship might even be punctuated with a “I really don’t care that much what happens to you” exclamation point that is furthered by a “As long as I get some milk and food every once in a while, and someone or something keeps me stimulated every once in a while I’ll continue to exist near you.”

Some might say the dog has as much, if not more, knowledge of our species as the cat, but the dog is biased. Dogs love us. They are so loyal that if they were commissioned to analyze our species, they would tell us what we want to hear. There’s a reason we call them man’s best friend, and it is largely based on the idea that they accept us for who we are. They don’t analyze us in the manner a cat will, and they know nothing about our inadequacies or failures, because their sole goal in life is to make us happy. They know when we’re happy, they’re happy. Cats are almost 180-degrees different.

Instagram posters have characterized this on again, off again, “I really don’t care that much what happens to you” relationship we have with cats with a somewhat humorous, somewhat condescending term that their cats use to describe us, hoomans. Hoomans is a cutesy eye-dialect, similar to that of the “No Girlz Allowed” sign that moviemakers put outside the door of a boy’s clubhouse. The cutesy error is employed to enhance the cutesy idea that cats and young boys can’t spell. The moviemakers might even add a backwards ‘R’ to further emphasize the cuteziness of the boy’s sign.

Instagram posters have characterized this on again, off again, “I really don’t care that much what happens to you” relationship we have with cats with a somewhat humorous, somewhat condescending term that their cats use to describe us, hoomans. Hoomans is a cutesy eye-dialect, similar to that of the “No Girlz Allowed” sign that moviemakers put outside the door of a boy’s clubhouse. The cutesy error is employed to enhance the cutesy idea that cats and young boys can’t spell. The moviemakers might even add a backwards ‘R’ to further emphasize the cuteziness of the boy’s sign.

Another intent behind the cutesy hoomans contrivance is to inform us that we’re not viewing this interaction from the customary human perspective. We’re viewing this particular interactions from a perspective we may not have considered before, the cat’s.

In that vein, the unsympathetic delineations of the cat would suggest there are Homo sapiens sapiens who fail the “advanced cognitive abilities, language, and complex social structures” standards put forth by biological anthropologists. They might suggest we introduce a Homo sapien confusocortex, or Confused Man, subspecies for those who haven’t evolved completely.

In that vein, the unsympathetic delineations of the cat would suggest there are Homo sapiens sapiens who fail the “advanced cognitive abilities, language, and complex social structures” standards put forth by biological anthropologists. They might suggest we introduce a Homo sapien confusocortex, or Confused Man, subspecies for those who haven’t evolved completely.

These hoomans were born at full capacity, and their schooling years proved that they were able to achieve full functionality, but as with any muscle, the brain can deteriorate with lack of use. We’re not attempting to make fun of them, but there is a delineation between those who know how to operate at an optimum, and those who fail to make necessary connections.

In the cat-world, I’m not sure if they would characterize me as a human or a hooman. I think they might develop a separate category for those of us who measure up, but we enjoy disrupting the meticulously crafted model they’ve created for human actions and reactions. The cats view such joyful interference with their carefully designed understanding of human nature and its patterns with something beyond skepticism. They’re alarmed. If we watch cats in the wild, they study their prey carefully to gauge whether or not they’ll get hurt. If after examining us completely, they developed a full categorization, it might be ha!men. My brief experience with cats informs me that they don’t have a sense of humor, so it would be impossible for them to properly categorize ha!men without some form of condescending insults. My guess is they would spit out something like, the symbolic, or ironic inversion of their cultural input often critiques the very idea of cultural output, then twist it into recursive satire. Their social systems resemble Escher prints—technically sound, emotionally disorienting. “They are players, jokesters, and fools,” the cats would conclude, “and we say that in the most condescending way possible.”

Ha!men know that pets and children create profiles of humans based on patterns, and I think cats are quite comfortable with the thought that hoomans were put on this planet to serve them. Hoomans are to provide the cat food, milk, a place to relieve themselves, and various forms of stimuli. It’s a tenuous relationship that suggests if hoomans fail to fulfill the expectations of their relationship the cat will simply go to another hooman who can. Those hoomans who fulfill expectations can, could, and probably should receive the reward of affection. They know adult hoomans need this every once in a while, and they don’t mind occasionally playing that role for them, as long as the bullet point, requirements are met.

Ha!men know that pets and children create profiles of humans based on patterns, and I think cats are quite comfortable with the thought that hoomans were put on this planet to serve them. Hoomans are to provide the cat food, milk, a place to relieve themselves, and various forms of stimuli. It’s a tenuous relationship that suggests if hoomans fail to fulfill the expectations of their relationship the cat will simply go to another hooman who can. Those hoomans who fulfill expectations can, could, and probably should receive the reward of affection. They know adult hoomans need this every once in a while, and they don’t mind occasionally playing that role for them, as long as the bullet point, requirements are met.

They also know we arrive home at around 5:30, feed them and themselves, and sit before the glowing box for a couple hours before it’s time to go to bed. They grow accustomed to these patterns, the way we conduct ourselves, the way we make sounds at one another, and our gait pattern. When we meet their criteria, they might sleep or find some other stimuli to occupy them, as they probably find most hoomans as boring as any other superior would find the actions of their underlings.

I don’t know cats would characterize me, but I highly doubt they would consider me boring. I’ve been their sole focus more times than I can count, and there have been occasions where these rooms housed a half-dozen people. I noticed how cats study us with more intensity than any other pet at a very young age, and I found it creepy in the beginning. “What are you looking at?” I wanted to ask, as if that would help matters. I noticed, early on, that when I acted somewhat out of sorts it only intensified their study of me. After numerous interactions over the years, I found their study of me fascinating, and I began tweaking my actions to destroy their research.

Just to be clear, I never touched one of these cats. I just enjoyed playing the role of their anecdotal information, their aberration. I exaggerated my differences just to be different than any other human they’d ever met, just to see how they’d react. The minute the cat owner I was dating left the room, I would walk across the room in a decidedly different gait pattern. I might slow turn my head to them in the manner an alien would in a movie, and I’d repeatedly stick my tongue out at them. I might even take a drink coaster and throw it across the room in an erratic manner. The list of things I did just to mess with their heads is long, but those are a few examples I remember. I’ve found that all we have to do is act a few deviations away from the normal hooman actions to make their pupils expand with increased scrutiny or fear.

Do the same things to a dog, and they might raise their head for a second, their ears might even perk, or they might even bring us a toy, thinking we want to play. Whatever they do, their reactions suggest they’re either less alarmed by abnormalities among the hoomen population, more forgiving of those who suffer from them, or they’re less intelligent than the cat and thus less prepared for an eventual aberration that cats foresee. Cats immediately switch to alert status. They don’t care for these games. If they don’t run from the room to avoid what they think could happen, they watch ha!men with unblinking, rapt attention. Even when they realize it’s just an act, as evidenced by our return to normalcy when the woman-owner returns to the room, they continue to study us. “I’ve decided that I don’t like you,” is the look they give us ha!men throughout.

***

Suzy Aldermann wasn’t a ha!men, but we thought she was. When we heard what happened at a corporate boardroom, we thought Suzy’s portrayal of a ha!man might’ve been one of the most brilliant portrayals we ever heard. Prior to that meeting, she appeared to abide by so many of the tenets of human patterns that when she deviated, we thought Suzy was employing a recursive inversion technique known to all ha!men as the perfect conceptual strategy for dismantling normative frameworks from within.

Suzy Aldermann wasn’t a ha!men, but we thought she was. When we heard what happened at a corporate boardroom, we thought Suzy’s portrayal of a ha!man might’ve been one of the most brilliant portrayals we ever heard. Prior to that meeting, she appeared to abide by so many of the tenets of human patterns that when she deviated, we thought Suzy was employing a recursive inversion technique known to all ha!men as the perfect conceptual strategy for dismantling normative frameworks from within.

Prior to her “full-fledged panic attack!” Suzy successfully presented herself as an individual of advanced cognitive abilities, language, and complex social structures. So, when she experienced this panic attack, this “full-fledged panic attack!” after she opened the door to a meeting room and saw Diana Pelzey conversating with her chum, we thought she brilliantly portrayed a ha!man to the uninformed. As the report goes, Suzy whispered to a friend that she would not be attending the meeting because Diana was present. “BRILLIANT!” we said. “Absolutely brilliant that Suzy would pick the least threatening person in the room to initiate her alleged panic attack!” We all agreed to keep Suzy’s ruse secret to see how it would play out, and we expected a lot of hilarious high-brow hi-jinx as a result. The joke, it turned out, was on us. We either overestimated Suzy or underestimated her, I’m still not sure which, but it became clear that Suzy decided to run away rather than up her game to match, and/or surpass Diana’s presentation. It was, according to Suzy, a full-fledged panic attack.

In the aftermath of our misreading, anytime we met a melodramatic hooman who was having a “full-fledged panic attack!” over a relatively insignificant issue, our instinctive response, based on our understanding of human patters is to think either she’s a ha!man who is joking, or she probably needs to experience some real problems in life to gain proper perspective.

Yet, when we’d talk to Suzy, she’d detail a relatively rough upbringing that included some eyebrow-raising experiences. Those incidents were real issues that Suzy had to manage, and she had to claw through the tumult to reach a resolution. The normal human progression, for those of us who study humans with relative intensity, is that when a human experiences a number of real problems, they become better at resolving them through experience. Suzy worked her way through all of those problems, but she never developed better problem, resolution skills.

We’ve all heard from other souls who purport to travel some tumultuous avenues. Wendi Hansen, for example, detailed for us her “rough life,” but when she was done, we couldn’t help but think that much of her self-imposed trauma was the socio-political equivalent of first-world problems. Suzy was no Wendi Hansen. Suzy’s issues were real and severe, and they were backed up by eye-witness testimony. Our natural assumption is that if she’s experienced problems far worse than a colleague purportedly interested in stealing her job, it would be nothing compared to what she’s experienced in real life.

If we were to view the humans, the ha!men, and the hoomans from the perspective of the Alien Life Form (ALF), or the cat, without empathy or sympathy, we would conclude that some humans get stronger, better, or gain a level of perspective that allows them to see minor problems for what they are in the moment. Some hoomen, on the other hand, deploy the tactical maneuver of retreat, and they do so, so often that they never fully develop their confrontational muscles.

After experiencing so many different souls who maneuver around their tumultuous terrains differently, I now wonder if hoomans, who’ve experienced real problems in life, blow otherwise insignificant issues up into real problems, because they’re more accustomed to handling their problems at that level. Either that or they know if they retreat during the relatively insignificant phase, it might never progress into more severe phases. Whatever the case is, their experiences have taught them that they can’t handle problems, and as a result of retreating so often, they never do.

***

“It’s a lie,” Angie Foote told me, regarding something Randy Dee told the group.

“It’s a lie,” Angie Foote told me, regarding something Randy Dee told the group.

“It’s not a lie,” I said. “It might be an exaggeration, a mischaracterization, or something he believes is true but is in fact false. It’s not what I would call a lie.”

“Barney, he told everyone that this is what he does, and I’ve seen how he does it. He doesn’t do it that way. He’s a durn liar is what I’m saying.”

Angie is what we in the biz call a simple truther. She sees everything in black and white. A truth is a truth, and a lie is a lie. There is no grey matter involved in her universe. I respect simple truthers in this vein, because I used to be one. I’m still one in many ways, but experiencing precedents in life can wreck the comfortable ideas we develop in our world of simple math and science. Facts are facts and truth is truth is their mantra.

Some of us hear a lie, and we know it’s a lie. When we’re telling lies, we know we’re lying, and we can’t help but view the rest of humanity from our perspective. When they’re lying, they know that one plus one equals two. I know it, you know it, and most importantly, they know it. We witnessed them doing one thing, and we heard them say they do something else, and they said it as if it was something they truly believed happened! How can they do that with a straight face?

My asterisk in the ointment, my new definition of a lie, is that a lie is something someone says that they know to be false. There are good liars who are so good at it that they can convince themselves that it’s true before they try to convince us. The other liars, the fascinating ones, fall into a greyer area. They don’t know they’re lying.

One of the most honest men I ever met, a Randy Dee, taught me the grey. Randy Dee told some whoppers. He told some untruths to me, regarding events that happened the previous night, and I was there for those events.

He misinterpreted the truth so often that it affected how I viewed him. When I viewed him, and the way he’d lie, I’d watch him with the rapt attention a cat would when encountering a ha!man who proved an aberration to my study of human patterns. While involved in this study, I became convinced that we could put a lie detector on him, and he’d pass with flying colors. “He’s just a durn liar!” I said to myself. Yet, if you knew this guy, and I did, you’d know he’s not lying, not in the strictest sense of the word. By the standard of taking everything we know about lying and inserting that into the equation, Randy Dee never told a lie.

I knew Randy well for a long time. I knew him so well that I learned he was incapable of lying. He was a law-and-order guy who despised deception and all of the other characteristics inherent in criminality. Yet, by our loose standards of truth v. lying, the man was a big, fat liar.

He was incapable of detecting the lies others told him, because he just didn’t think that way. He was somewhat naive in that regard, and after getting to know him well, I considered it almost laughable that anyone would consider him a liar.

Randy Dee was an unprecedented experience for me, and I would have a lot to sort through before I fully understood what I was experiencing with him. If we took this to a social court with a simple truther sitting in the role of a judge, we would experience an exchange of “He’s lying.” ‘I’m telling you he’s not. You have to get to know him.’ “You’re over-thinking this.” ‘If you know the guy as well as I do, you’d know he’s incapable of lying.’ “All right, he’s an idiot then.” ‘If idiot suggests a lack of intelligence,’ I would reply, ‘You have to meet him to know he’s anything but.’

If this argument reached the point of no-return, one of us might suggest using a lie detector. If Randy Dee passed the lie-detector test, the simple truther would then suggest that there was something wrong with that mechanism, and there might be.

When lie detectors first entered the scene, their findings were considered germane to cases. Judges, lawyers, and juries not only thought their findings should be admissible in proceedings, they considered them germane to findings.

“Did he take a lie detector test?” a judge might ask. “Yes, your honor,” the defense attorney said, “and he passed with flying colors.” Lie detectors eventually became less prominent, because they were deemed wildly inconsistent. How can a machine with no powers of empathy, sympathy, or any emotions differentiate between hoomens, ha!men, and humans to produce inconsistent findings? What progressions occurred? Were so many Ha!men and Hooman able to beat lie detectors so often that the machines lost their relevance in criminal cases?

Randy Dee, a man who was so honest that it seemed almost ridiculous to suggest otherwise taught me that the reason lie detectors are wildly inconsistent has more to do with the idea that we’re wildly inconsistent. We can convince ourselves of a lie, so thoroughly, that it’s not a lie anymore, and we can do it without ever trying to deceive anyone or anything in the case of lie detectors. Ha!men might do it just to see if they can defeat the machine, and its ability to detect different biological reactions, but hoomens might do it because they lose the ability to make those necessary connections that produce truth. The latter provides a wild ride to those of us who once viewed human nature in the ritualistic patterns cats will, and if we continue to view hoomens with the rapt attention a cat gives a Ha!man, until we find the truth, it will wreck every simplistic truth we thought we knew about lying liars and the lies they tell.