Marlon Brando was by many accounts the greatest actor who ever graced stage and screen. Peers, fans, and critics found his performances explosive, electric, and affecting. He had a way of connecting to the audience in a way that left us trying to remember the other members of the cast, and he was teamed with some of the greatest actors in the world in most of his movies. Marlon Brando was such a great actor that he changed acting at twenty-seven-years old. He captivated so many hearts and minds so early in his career that the field of acting bored him.

“[Marlon] Brando did not merely act the role, he became the part, allowing the role to seep into his pores, so that he stalked the screen like a young lion. Critics were stunned, blown away by the realism of the performance, they had simply never seen anything like him before.” —TheCinemaholic

Brando was the first movie star, to my mind, to publicly state that he was not the least bit grateful for the roles, the career, and the life his profession offered him. Why would a person who made enough money throughout his career to purchase his own island not be grateful for everything the acting profession gave him? The answer appears multifaceted and vague, but we can speculate that the core reason was that he achieved such rarified air so early on in his career that no one could humble him. His early work influenced the biggest stars of his era to be more real and find the element of truth in their work, and we can speculate that that level of adulation stunted his growth and left him an immature narcissist.

Brando was the first movie star, to my mind, to publicly state that he was not the least bit grateful for the roles, the career, and the life his profession offered him. Why would a person who made enough money throughout his career to purchase his own island not be grateful for everything the acting profession gave him? The answer appears multifaceted and vague, but we can speculate that the core reason was that he achieved such rarified air so early on in his career that no one could humble him. His early work influenced the biggest stars of his era to be more real and find the element of truth in their work, and we can speculate that that level of adulation stunted his growth and left him an immature narcissist.

Marlon Brando didn’t care what critics thought of his performances, and he didn’t care what movie moguls, most directors, producers, or anyone behind the scenes thought of them either. Those of us who love great art might applaud this indifference, as it basically defines the term auteur, or an individual whose style and complete control give a performance its personal and unique stamp. After doing this so often in his career, Marlon Brando earned a place in the rarified air of those who don’t have to care anymore to continue to prosper in their career. If you just stood to applaud this artistic apathy, the idea that he didn’t care what you might think either, should sit you back down.

As an incredible artist, and Marlon Brando was an incredible artist, we shouldn’t expect an artist to create art for us. As a side note, we should note that no actor creates art, but they can bring a writer’s character to life for us. They can interpret or reimagine a character in a way the writer never imagined. They can make the character their own. Does anyone know Budd Schulberg, the screenwriter of On the Waterfront? How about Tennessee Williams, the writer of A Streetcar Named Desire? He’s historically famous, as is Mario Puzo, writer of The Godfather, but most of us know those movies as Marlon Brando movies. His performances in these movies were so great that he overshadowed everyone else involved in them. Yet, we shouldn’t expect him to act in a manner that pays homage to his fans, and we shouldn’t care why anyone strives to give their best performances every time out, as long as they do.

Having said that, there is something special about a great movie. We can lose ourselves in the time it takes to watch a movie. We can forget about our problems, and our need to get some sleep. If you’ve ever had a phone call disrupt a great movie, you know how deep into that movie you were. We develop deep connections to story the writer’s write, the manipulation of a great director, and the performance of the movie’s actors. We might develop such a deep connection to the actor that we develop a relationship with them. For some of us that relationship is all about loyalty, as we’ll see anything and everything that actor has ever done. Others expect the star to be nice to them in restaurants and other public venues to enhance that relationship. The point is, we accidentally grow to expect some level of appreciation for all that we’ve given them, even if it’s just some relatively insignificant comment they make on a talk show.

“Acting is just making faces. It’s not a serious profession,” Marlon Brando told Lawrence Grobel in Conversations with Marlon Brando in 1989. “Acting is not a profession that I have any great respect for… It’s something I do, but it’s not something I think is particularly noble,” Brando told Edward R. Murrow in a 1955 interview. “I think it’s a silly, childish thing to do for a living… I don’t think it’s a very dignified way to make a living,” he told Dick Cavett in a 1973 interview.

I don’t know if Brando was the first movie star to go out of his way to publicly damage our illusion that they care what we think. He did open the door for actors to publicly demean and diminish the iconic roles that created their careers. If they state that they now want to move past that signature role that made them famous, we’d understand such competitive instincts, but they now say that they’re embarrassed by those roles that made them famous. (Note: I never found a quote where Brando singled out a performance that embarrassed him.) To try to be fair to those who say these things, we can sympathize with the idea that it has to be tedious to hear someone say, “Hey, aren’t you Han Solo!” eighty movies and fifty years after he gave that iconic performance. Yet, to be so ungrateful that they’re not afraid to publicly state that they’re embarrassed by a role which we all still love, and one that spawned a career that may not have happened if not for that role, just sits in my craw in a way that cannot be removed mentally, biologically or surgically.

I don’t know if Brando was the first movie star to go out of his way to publicly damage our illusion that they care what we think. He did open the door for actors to publicly demean and diminish the iconic roles that created their careers. If they state that they now want to move past that signature role that made them famous, we’d understand such competitive instincts, but they now say that they’re embarrassed by those roles that made them famous. (Note: I never found a quote where Brando singled out a performance that embarrassed him.) To try to be fair to those who say these things, we can sympathize with the idea that it has to be tedious to hear someone say, “Hey, aren’t you Han Solo!” eighty movies and fifty years after he gave that iconic performance. Yet, to be so ungrateful that they’re not afraid to publicly state that they’re embarrassed by a role which we all still love, and one that spawned a career that may not have happened if not for that role, just sits in my craw in a way that cannot be removed mentally, biologically or surgically.

***

Marlon Brando, a man many consider the best actor of his generation, didn’t care about acting, and he didn’t care for it. Did he say these things, because he thought it was cool not to care? Impossible, we say, that’s so high school, This man was a legendary actor who almost single-handedly changed the way actors approached their profession. Was it a marketing technique? If we read through Brando’s interviews, and the books written about him that give us insight into his thought process, Brando didn’t care about image, marketing, or any form of public relations. When we strip all that away, we’re left with the speculation that either Marlon Brando loathed himself so much that he viewed everything he did in a negative manner, or he said such things because he wanted us to think he was cool.

When our starting quarterback privately told us he didn’t care about football, soon after winning a state championship, we thought that was “so cool!” He was something of a mythic figure to us, basically telling us to not get so worked up about a silly game. That was high school though, filled with teenagers climbing all over one another to find new and different ways to be cool. Is it possible that this near-mythic figure of the acting world tried to accomplish the same thing by telling his fans to not get so worked up about something as silly as movies? We never leave high school, some social commentators say, and we never totally abandon the need to have others consider the fact that we don’t care about nothing “so cool!”

It was His Technique to Not Care

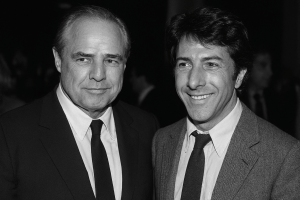

“Marlon Brando would often talk to cameramen and fellow actors about their weekend even after the director would call action. Once Brando felt he could deliver the dialogue as naturally as that conversation, he would start the dialogue.” —Dustin Hoffman in his online Masterclass.

Hoffman’s quote suggests that Brando found a technique to help him calm his nerves, and it helped him mentally overcome the idea that he had to top his previous performances. By talking to these people the way he did, Brando helped himself find a middle ground, a place where he could not care so much. It suggests that he tried to place himself in a more natural setting, convincing himself that he didn’t care, and he did it to achieve a better performance. It’s possible, even plausible, but my guess is Hoffman is over-interpreting Brando’s casual conversations.

Hoffman’s quote suggests that Brando found a technique to help him calm his nerves, and it helped him mentally overcome the idea that he had to top his previous performances. By talking to these people the way he did, Brando helped himself find a middle ground, a place where he could not care so much. It suggests that he tried to place himself in a more natural setting, convincing himself that he didn’t care, and he did it to achieve a better performance. It’s possible, even plausible, but my guess is Hoffman is over-interpreting Brando’s casual conversations.

Even some of his fellow actors, his peers, considered him the greatest actor who ever lived, the greatest of all time, the GOAT of the acting world. Whenever we label someone the GOAT, the next chapter of the narrative involves their single-minded obsession, the drive to be the best, the sacrifices he made to be the best, and the measures he took to stay on top. “To be the best, you must beat the rest,” is some semblance of a quote these individuals drop to describe their drive to be the best.

That is all true for most GOATs in sports, because even the most naturally gifted athletes must push themselves beyond their natural abilities to sustain continued dominance of those of equal, natural abilities. Brando’s success in the field of acting suggests this isn’t the case with acting. It doesn’t matter if you’re driven to succeed or obsessed with a level of success that continues to outshine your peers. They just need to look great on screen, deliver their lines on time, and do so in a manner suited for the role.

Yet, Brando didn’t always look great on screen, as he often showed up, on set, overweight in the latter half of his career, but his iconic status at that point was such that he didn’t have to be in shape to get roles. It was a little sad to see the man so old and out of shape in his latter movies, but it was still a treat to see him on screen. We didn’t care if he delivered his lines well, yet he often mumbled his lines, which was probably caused by his refusal to memorize them. To compensate for his refusal to memorize lines, directors had their people put placards around the setting for him to read. So, at least in the latter half of his career, he was reading lines to us.

Anytime we criticize the great ones, we hear excuses and obfuscations. “Brando cared,” his supporters say. “He cared so much that one of his acting techniques involved getting to a place where he didn’t care anymore.” This was Marlon Brando’s technique, they argue, and we call that technique method acting, but according to the book Songs my Mother Taught Me, Brando abhorred the ideas behind method acting, as taught by Lee Strasberg.

“After I had some success, Lee Strasberg tried to take credit for teaching me how to act. He never taught me anything. He would have claimed credit for the sun and the moon if he believed he could get away with it. He was an ambitious, selfish man who exploited the people who attended the Actors Studio and tried to project himself as an acting oracle and guru. Some people worshipped him, but I never knew why. I sometimes went to the Actors Studio on Saturday mornings because Elia Kazan was teaching, and there were usually a lot of good-looking girls, but Strasberg never taught me acting. Stella (Adler) did—and later Kazan.”

As the “greatest actor in the world” who could command huge paychecks, because he could attract large audiences to his performances, Brando could’ve changed acting for a wide array of actors.

In his 2015 documentary, Listen To Me Marlon, Brando said that prior to his appearance on the scene, “Actors were like breakfast cereals, meaning they were predictable. Critics would later say that this was Brando being difficult, but actors who worked opposite him said it was just all part of his technique.”

Christopher Reeves responded to these characterizations when asked about what working with the great Brando on the set of 1978’s Superman was like, “I don’t worship at the altar of Marlon Brando, because I feel that he’s copped out in a certain way. He’s no longer in the leadership position he could be. He could really be inspiring to a whole generation of actors and by continuing to work, but what happened is the press loved him whether he was good, bad, or indifferent. People thought he was this institution no matter what he did. So, he doesn’t care anymore, and I just think it would be sad to be fifty-three, or whatever he is and not give a damn. I just think it’s too bad to be forced into that kind of hostility. He could be a real leader for us.” Speaking specifically on the role Brando played in Superman, Reeves added, “He took the $2 million ($19 million with today’s inflation) and ran you know.”

Christopher Reeves responded to these characterizations when asked about what working with the great Brando on the set of 1978’s Superman was like, “I don’t worship at the altar of Marlon Brando, because I feel that he’s copped out in a certain way. He’s no longer in the leadership position he could be. He could really be inspiring to a whole generation of actors and by continuing to work, but what happened is the press loved him whether he was good, bad, or indifferent. People thought he was this institution no matter what he did. So, he doesn’t care anymore, and I just think it would be sad to be fifty-three, or whatever he is and not give a damn. I just think it’s too bad to be forced into that kind of hostility. He could be a real leader for us.” Speaking specifically on the role Brando played in Superman, Reeves added, “He took the $2 million ($19 million with today’s inflation) and ran you know.”

If we watch that Reeves interview on Late Night with David Letterman, we can tell Reeves was all worked up about this topic, after working with Brando. Reeves acted as if he couldn’t wait for Letterman’s question, because he wanted to get his experience of working with Brando off his chest.

Tallulah Bankhead, who co-starred with Brando in his first stage performance back in 1947, also clashed with the actor before firing him. She recommended him for the part of Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire. “[He was] a total pig of a man without sensitivity or grace of any kind.” Even she had to admit, though, that Brando had talent. “There were a few times when he was really magnificent,” Bankhead said. “He was a great young actor when he wanted to be.” (My emphasis.)

We can leave the final word to another acting great, Jack Nicholson, who was famously intimidated by Brando’s talent while working with him. Nicholson once joked, “When Marlon dies, everyone moves up one.”

“I watched some of Brando’s dailies, nine or ten takes of this same scene. Each take was an art film in itself. I sat there stunned by the variety, the depth, the amount of silent articulation of what a scene meant. The next day I woke up completely destroyed. The full catastrophe of it hit me overnight,” Nicholson reminisced.

“I watched some of Brando’s dailies, nine or ten takes of this same scene. Each take was an art film in itself. I sat there stunned by the variety, the depth, the amount of silent articulation of what a scene meant. The next day I woke up completely destroyed. The full catastrophe of it hit me overnight,” Nicholson reminisced.

He also summarized neatly the ubiquitous reach of Brando’s influence throughout the world of film acting, in one short sentence: “We are all Brando’s children.” He was speaking for many an acting great, from Pacino to Hopper, Christopher Reeve, Viggo Mortensen, and too many others to mention.

Did Brando care about any of that? When he cared, he cared. When he had a script that supported a cause he believed in, he cared. He didn’t care about Superman, but he got paid so much to star in it that he probably should’ve. He had been the biggest star in the world for so long that he stopped caring about it. He didn’t appreciate his standing in the world for what it was, at the time, and he didn’t really care when it ended. He read his lines, and he did his job.

The next question, and it’s one I usually loathe when it comes to innovators, disruptors, and enterprising young minds who create. The line goes like this, “If he hadn’t invented this, someone would have eventually.” They say this when the subject of Nikola Tesla, Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton or any innovators notions, products, or inventions are discussed. They say this when another suggests they were indispensable on the timeline. Was Marlon Brando, and his influence on acting indispensable? Method acting and the new brand of “realism” that Brando learned and displayed for the world may not have been as immediately accepted, applauded, or adopted if Marlon Brando never existed, but the techniques Brando used were being taught in acting schools. Some suggest that if Brando never existed, Montgomery Clift would taken those techniques to the world. As great an actor as Clift was, he wasn’t the explosive “shining star” Brando proved to be.

When the subject of movie stars arrives, most of us make it all about “me.” We judge them based on how nice they were to “me.” “You think he wasn’t nice? He was nice to me. He even went so far as to say something nice to my son.” We also view movie stars, sport stars, and all celebrities based on our brief encounter with them, because we want to be a part of the story. “He didn’t me tip well,” “She said she doesn’t do autographs,” or “They didn’t even so much as look at me throughout our Uber.” I try very hard to avoid making it about “me.”

I met a number of celebrities in a previous life, and I found their particular demographic similar to all of the other ones. Some celebrities went out of their way to be nice to me. Some were dismissive, and others were rude, but most of them treated me the way everyone else does, and I never really cared one way or another. Most of us do. We loved their movie so much “we” bought that movie on DVD, “we” have three of their songs memorized, and “we” developed a connection to them that “we” thought they should consider special. When they didn’t reciprocate in anyway, “we” felt they diminished our special moment. When they didn’t tip us according to expectations, we went to Facebook to report them. When they refused to join us in a selfie, refused a request for an autograph, or even offer us a hearty smile or handshake, we proclaimed we’d never watch one of their movies again. We can’t help it, we judge people, places, and things from our perspective. On this particular note, I might agree with Brando’s general assessment that we all get a little silly about movies.

Thus, if I met the late, great actor, and he dismissed me as pond scum, I wouldn’t be anymore insulted by that comment than if anyone else said it. It’s the general sense of a lack of appreciation that sticks in my craw. If he ever dismissed the role of The Godfather, which he didn’t to my knowledge, as “reading lines and making faces”, I wouldn’t find it personally insulting, even though I connected with that character so much I felt a personal relationship with it. I would be angry though. I would be angry that a man who was given such an incredible opportunity in life to affect so many people didn’t appreciate it in the least, and that appears to be the case with the greatest actor who ever lived, Marlon Brando.