On the timeline of comedy, the subversive nature of it became so comprehensive that it became uniform, conventional, and in need of total destruction. Although the late, great Andy Kaufman may never have intended to undermine and, thus, destroy the top talent of his generation, his act revealed his contemporaries for what they were: conventional comedians operating under a like-minded banner. In doing so, Andy Kaufman created a new art form.

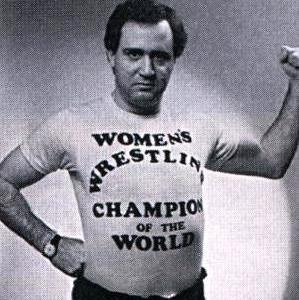

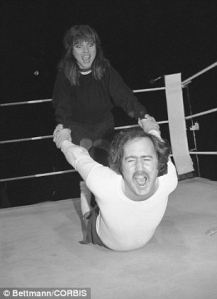

Some say they enjoyed Andy Kaufman’s character on Taxi, and they enjoyed some of his other performances in tightly scripted roles as a comedic actor, but his solo stage performances weren’t funny. They weren’t funny. They were unfunny, and they were so unfunny they were hilarious. If you saw his act, and I did on tape, you knew he wasn’t going for funny. He stood on stage in the manner a typical standup comedian would, and the audience sat in their seats as a typical audience will. The lines began to blur almost immediately after Kaufman took the stage. What is the joke here? Is he telling jokes? Am I in on it? They didn’t get it, but Andy Kaufman didn’t want us to get it. After he became famous, more people started to get it, so his act evolved, naturally, to wrestling women.

After reading every book written about him, watching every YouTube video on him, and watching every VHS tape ever made with him in it, I gained some objectivity. My guess is that he wasn’t talented enough to succeed as a “conventional artist”. He didn’t have oodles of material to fall back on, and he wasn’t a prolific writer. He wasn’t a one-trick pony, but he wasn’t a thoroughbred who could have a long, multi-faceted career either. Whatever it was that he did, it was something we had to see, and he did it better than anyone else ever has. If you don’t “get it”, and few do, then you never will. That’s not intended as a slam on the reader, because he didn’t want us to get it. Andy Kaufman’s M.O. was a little bit childish and narcissistic, but in many ways his “overly simplistic” acts somehow ended up redefining and revolutionizing comedy. If you saw it back then, you see it now all over comedy.

After reading every book written about him, watching every YouTube video on him, and watching every VHS tape ever made with him in it, I gained some objectivity. My guess is that he wasn’t talented enough to succeed as a “conventional artist”. He didn’t have oodles of material to fall back on, and he wasn’t a prolific writer. He wasn’t a one-trick pony, but he wasn’t a thoroughbred who could have a long, multi-faceted career either. Whatever it was that he did, it was something we had to see, and he did it better than anyone else ever has. If you don’t “get it”, and few do, then you never will. That’s not intended as a slam on the reader, because he didn’t want us to get it. Andy Kaufman’s M.O. was a little bit childish and narcissistic, but in many ways his “overly simplistic” acts somehow ended up redefining and revolutionizing comedy. If you saw it back then, you see it now all over comedy.

Those of us who had an unnatural attraction to Kaufman’s game-changing brand of unfunny comedy now know the man was oblivious to greater concerns, but we used whatever it was he created to subvert conventional subversions, until they lost their subversive quality for us.

Those “in the know” drew up very distinct, sociopolitical definitions of subversion long before Andy Kaufman. They may consider Kaufman comedic genius now, but they had no idea what he was doing while he was doing it. I can only guess that most of those who saw Kaufman’s act in its gestational period cautioned him against going overdoing it.

“I see what you’re trying to do. I do,” I imagine them saying, “but I don’t think this will play well in Kansas. They’ll just think you’re weird, and weird doesn’t play well on the national stage, unless you’re funny-weird.”

Many of them regarded being weird, in the manner embodied by his definition of that beautiful adjective as just plain weird, even idiotic. They didn’t understand what he was doing.

Before Andy Kaufman became Andy Kaufman, and his definition of weird defined it as a transcendent art form, being weird meant going so far over-the-top that the audience felt comfortable with the notion of a comedian being weird. It required the comedic player to find a way to communicate a simple message to the audience: “I’m not really weird. I’m just acting weird.” Before Kaufman, and those influenced by his brilliance, broke the mold on weird, comedians relied on visual cues, in the form of weird facial expressions, vocal inflections, and tones so weird that the so-called less sophisticated audiences in Kansas could understand the notion of a comedic actor just being weird. Before Kaufman, comedic actors had no interest in taking audiences to uncomfortable places. They just wanted the laugh.

One can be sure that before Andy Kaufman took to the national stage on Saturday Night Live, he heard the warnings from many corners, but for whatever reason he didn’t heed them. It’s possible that Kaufman was just that weird, and that he thought his only path to success was to let his freak flag fly. It’s also possible that this is just who Andy Kaufman was. Those who haven’t read the many books about him, watched the VHS tapes, the YouTube videos, and the podcasts had no idea what he was doing, but he had enough confidence in his act to ignore the advice from those in the know. We admirers must also concede that it’s possible Kaufman might not have been talented enough to be funny in a more conventional sense. Whatever the case, Kaufman maintained his unconventional, unfunny, idiotic characters and bits until those “in the know” declared him one of the funniest men who ever lived.

One can be sure that before Andy Kaufman took to the national stage on Saturday Night Live, he heard the warnings from many corners, but for whatever reason he didn’t heed them. It’s possible that Kaufman was just that weird, and that he thought his only path to success was to let his freak flag fly. It’s also possible that this is just who Andy Kaufman was. Those who haven’t read the many books about him, watched the VHS tapes, the YouTube videos, and the podcasts had no idea what he was doing, but he had enough confidence in his act to ignore the advice from those in the know. We admirers must also concede that it’s possible Kaufman might not have been talented enough to be funny in a more conventional sense. Whatever the case, Kaufman maintained his unconventional, unfunny, idiotic characters and bits until those “in the know” declared him one of the funniest men who ever lived.

The cutting-edge, comedic intelligentsia now discuss the deceased Kaufman in a frame that suggests they were onto his act the whole time. They weren’t. They didn’t get it. I didn’t get it, but I was young, and I needed the assistance of repetition to lead me to the genius of being an authentic idiot, until I busied myself trying to carve out my own path to true idiocy, in my own little world.

Andy Kaufman may not have been the first true idiot in the pantheon of comedy, but for those of us who witnessed his hilariously unfunny, idiotic behavior, it opened us up to a completely new world. We knew how to be idiots, but we didn’t understand the finer points of the elusive art of persuading another of our inferiority until Kaufman came along, broke that door down, and showed us all his furniture.

For those who’ve never watched Andy Kaufman at work, his claim to fame did not involve jokes. His modus operandi involved situational humor. The situations he manufactured weren’t funny either, not in the traditionally conventional, subversive sense. Some of the situations he created were so unfunny and so unnerving that viewers deemed them idiotic. Kaufman was so idiotic that many believed his shows were nothing more than a series of improvised situations in which he reacted on the fly to a bunch of idiotic stuff, but what most of those in the know could not comprehend at the time was that everything he did was methodical, meticulous, and choreographed.

Being Unfunny and Idiotic in Real-life Situations

This might involve some speculative interpretation, but I think Andy Kaufman was one of the first purveyors of the knuckleball in comedy. Like the knuckleball, the manner in which situational humor evolves can grow better or worse as the game goes on, but eventual success requires unshakeable devotion to the pitch. The knuckleballer will give up a lot of walks, and home runs, and they will knock the occasional mascot down with a wild pitch, but for situational jokes to be effective, they can’t just be another pitch in our arsenal. This pitch requires a level of commitment that will become a level that eventuates into a lifestyle that even those closest to us will have a difficult time understanding.

“Why would you try to confuse people?” they will ask. “Why do you continue to say jokes that aren’t funny?”

“I would like someone, somewhere to one day consider me an idiot,” the devoted will respond. “Any idiot can fall down a flight of stairs, trip over a heat register, and engage in the fine art of slapstick comedy, but I want to achieve a form of idiocy that leads others to believe I am a total idiot who doesn’t know any better.”

“I would like someone, somewhere to one day consider me an idiot,” the devoted will respond. “Any idiot can fall down a flight of stairs, trip over a heat register, and engage in the fine art of slapstick comedy, but I want to achieve a form of idiocy that leads others to believe I am a total idiot who doesn’t know any better.”

For those less confident in their modus operandi, high-minded responses might answer the question in a way that the recipient considers us more intelligent, but those responses obfuscate the truth regarding why we enjoy doing it. The truth may be that we know the path to achieving laughter from our audience through the various pitches and rhythms made available to us in movies and primetime sitcoms, but some of us reach a point when that master template begins to bore us. Others may recognize, at some point in their lives, that they don’t have the wherewithal to match the delivery that their funny friends employ, particularly those friends with gameshow host personalities. For these people, the raison d’être of Kaufman’s idiotology may offer an end run around to traditional modes of comedy. Some employ these tactics as a means of standing out and above the fray, while others enjoy the superiority-through-inferiority psychological base this mindset procures. The one certain truth is that most find themselves unable to identify the exact reason why they do what they do. They just know they enjoy it, and they will continue to pursue it no matter how many poison-tipped arrows come their way.

An acquaintance of mine learned of my devotion to this pitch when she overheard me contrast it in a conversation I had with a third party in her proximity. I did not want to have that conversation with the third party so close to her, but my devotion to the pitch was not so great that I was willing to be rude to that other person. What she overheard was a brief display of intellectual prowess that crushed her previous characterizations of me. When I turned back to her to continue the discussion she and I were having prior to the interruption, her mouth was hanging open, and her eyes were wide. The remark she made in that moment was one she repeated throughout our friendship.

“I am onto you now,” she said. “You are not as dumb as you pretend to be.”

The delicious moment of confusion occurred seconds later, when it dawned on her that what she thought she figured out made no sense in conventional constructs. 99% of conversationalists pretend to be smart, and the traditional gauge of the listener involves them defining the speaker’s perceived intelligence downward, as they continue to speak and leak their weaknesses in this regard. What I did was not reveal some jaw-dropping level intellect but a degree of knowledge that served to upend her traditional study of those around her to define their level of intelligence.

She looked at me with pride after she figured me out, but that look faded when she digested what she thought she figured out. Who pretends to be dumb and inferior? was a thought I could see in the fade.

What are you up to? was the look she gave me every time I attempted to perpetuate ignorance thereafter. The looks she gave me led me to believe that everything she thought she figured out only brought more questions to the fore. I imagined that something of a flowchart developed in her mind to explain everything I did and said to that point, and that each flowchart ended in a rabbit hole that once entered into would place her in a variety of vulnerable positions, including the beginning. She pursued me after that, just to inform me that she was onto what I was doing, until it became obvious that she was the primary audience of her own pleas.

I’ve never thrown an actual knuckleball with any success, but watching her flail at the gradual progression of my situational joke, trying to convince me that she was now above the fray, cemented my lifelong theory: Jokes can be funny, but reactions are hilarious.

The point is that if you devote yourself to this mindset, and you try your hardest not to let your opponents see the stitches, you can convince some of the people, some of the times, that you are an idiot.

The Idiotology

Some idiots purchased every VHS tape and book we could find on Andy Kaufman, and we read every internet article that carried his name to try to unlock the mystery of what he was trying to do. We wanted those who knew him best to tell us why he chose to go against the advice of those in the know and if it was possible for us to follow his indefinable passion to some end. We followed his examples and teachings in the manner of disciples, until it became a lifestyle. Andy Kaufman led us to believe that if we could confuse the sensibilities of serious world just enough that it could lead to some seminal moments in our pursuit of the idiotic life.

If our goals were to be funny, we would’ve attempted to follow the trail laid by Jerry Seinfeld. If our aim was only to be weird-funny, we would’ve adopted the weird-funny voice Steve Martin used in The Jerk. If we wanted to be sardonic or satirical, we would have looked to George Carlin for guidance. We knew we weren’t as funny as any of those men were, but we reached a point when that didn’t matter to us. When we discovered the unfunny, subversive idiocy of Andy Kaufman, however, it filled us like water rushing down the gullet of a dehydrated man.

“How did the unfunny idiot reach the point where it no longer mattered that others considered them funny?” the reader might ask. “How did you reach the point where that bored you?” The natural inclination most might have is that we think were so funny for so long that we sought something more. This was not the case for us, as most people, especially women, never thought we were funny. The answer, if there is one, is that, like Andy Kaufman, we might not be as funny or as talented as our friends, but we choose not to see it that way of course. The unfunny idiot is just thrilled as anyone else when others find them funny, even by conventional means, but there’s something different and unusually thrilling to us when we deliver a crushing haymaker that no one finds funny, per se, and most people consider idiotic. “Okay, right there, you said it, you said it,” an especially perspicacious individual might say, “You find it unusually thrilling. Why?” When pressed to the mat, and if we do it long enough someone will call us out on it and interrogate, until they help us arrive at an answer, such as, we don’t know, but we were probably just wired a little different.

Most of our friends considered us weird for the sake of being weird, but they don’t recognize the depth charges until they’re detonated. If we do it just right, and knuckleball slides under the bat perfectly, they’ll see it for what it is. They might not understand it, but they’ll get it. They won’t feel foolish for not getting it, because you were the idiot in that scenario, but they’ll eventually see that you weren’t being weird just for the sake of being weird.

The Disclaimer

If the goal of the reader is to have their friends and co-workers consider them funny, adding Kaufman’s knuckleball to your repertoire will only lead to heartache and headaches. What we advise, instead, is for the reader to focus on adding more traditional beats and rhythm to their delivery, and they should learn how to incorporate them, on a situational basis, into conversations. This gets easier with practice and time. Quality humor, like quality music, must offer pleasing beats and rhythms that find a familiar home within the audience’s mind. (Some suggest that the best beats and rhythm of humor come in threes. Two is not as funny as three, and four is too much more.) To achieve familiarity, there are few resources more familiar than that which comes from sitcoms and standup comedians that everyone knows and loves. We should also copy the template our friends lay out for a definition of what’s funny. There’s nothing an audience loves more than repeating their jokes, rhythms and beats, right back at them. If the joke teller leads into the punchline with a familiar rhythm and lands on the line in a familiar beat, the audience’s reward for figuring out that beat will be a shot of dopamine, and the joke teller’s reward is the resulting laughter. To keep things fresh, the joke teller might want to consider providing their audience a slight, yet still pleasing, twist at the end. The latter can be funny as long as the punchline is a slight slide away from expectations.

If, however, the goal is to be an unfunny idiot who receives no immediate laughter, the joke teller still needs to adhere to the standardized rules of comedic beats and rhythms, and they need to know them even better than students of traditional humor do. As any gifted practitioner of the art of idiocy will tell those willing to listen, it is far more difficult to find a way to distort and destroy the perception of conventional humor than it is to abide by it. This takes practice and practice in the art of practice, as Andy Kaufman displayed.

The rewards for being a total idiot are few and far between. If we achieve total destruction or distortion of what others know to be the beats and rhythm of humor, a sympathetic soul might consider us such an idiot that they take us aside to advise us about our beats and the rhythm of our delivery. For the most part, however, the rewards idiots receive are damage to their reputations as potentially funny people. Most will dismiss us as weird, and others might even categorically dismiss us as strange. Still others will dismiss us as idiots who know nothing about making people laugh. Most will want to have little to nothing to do with us. Women, in particular, might claim they don’t want to date us, declaring, “I prefer nice, funny guys. You? I’m sorry to say this, but you’ve said so many weird things over the years that … I kind of consider you an idiot.”