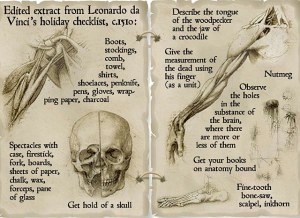

“Describe the tongue of the woodpecker and the jaw of the crocodile,” Leonardo da Vinci wrote as a reminder to himself in his Codex Atlanticus.

How many of you are curious about inconsequential matters? Let’s see a show of hands. How many of those curiosities will end up serving something greater? Some will and some might, you never know. We could end up studying something largely consider inconsequential that ends up helping us understand ourselves better, our relationship to nature, and all of interconnected facets of our ecosystem. What seems inconsequential in the beginning can prove anything but in other words, but what would purpose could the study of a bird’s tongue serve a 16 th century artist?

“Everything connects to everything else,” a modern da Vinci might have answered. There is no evidence that the 15th and 16th century Leonardo da Vinci ever said, or wrote, those words, and it’s likely apocryphal or a 20thcentury distillation of Leonardo’s notebook passages on the unity of nature, such as the earth-man analogy he made in the Codex Leicester or water’s role in the Codex Atlanticus. So, the answer is da Vinci studied the woodpecker’s tongue to try to find a greater connection, right? Maybe, sort of, and I guess in a roundabout way. When we study da Vinci’s modus operandi, we discover that his research did involve trying to find answers, but his primary focus was to try to find questions. He was, as art historian said, Kenneth Clark said, “The most relentlessly curious.” That characterization might answer our questions with a broad brush, but it doesn’t answer the specific question why even the most relentlessly curious mind would drill so far down to the tongue of the woodpecker for answers. For that, we turn back to the theme we’ve attributed to da Vinci’s works “Everything connects to everything else.” He wasn’t searching with a purpose, in other words, he was searching for a purpose of the purpose of the tongue.

We’ve all witnessed woodpeckers knocking away at a tree. Depending on where we live, it’s probably not something we hear so often that it fades into the background. When we hear it, we stop, we try to locate it, and we move on. Why do they knock? Why does any animal do what they do? To get food. Yet, how many of us have considered the potential damage all that knocking could have on the woodpecker’s brain? If another animal did that, it could result in headaches, concussions, and possible long term brain damage. How does a woodpecker avoid all of that? Prior to writing this article, I never asked how the woodpecker avoided injury, because I never delved that deep into that question, because why would I? As with 99.9% of the world, I just assumed that nature always takes care of itself somehow. As curious as some of us are, da Vinci’s question introduces to the idea that we’re not nearly as curious as we thought.

Was da Vinci one of the most relentlessly curious minds that ever existed, or was he scatterbrained? We have to give him points for the former, for even wondering about the woodpecker’s tongue and the crocodile’s jaw, but the idea that he we have no evidence that he pursued these questions gives credence to the latter.

Did he find the fresh carcass of a woodpecker to discover how long the tongue was relative to the small bird, and its comparatively small head? Did he initially believe that the extent of its functionality involved helping the bird hammer into wood, clear wood chips, and/or create a nest. If his note was devoted to what he saw the bird do, he probably saw it perform all of these chores, coupled with using it to retrieve ants and grubs from the hole its knocking created. If da Vinci watched the bird, he probably saw what every other observer could see. It doesn’t seem characteristic to da Vinci to leave his conclusions to superficial observations, but I have not found a conclusion in da Vinci’s journal to suggest that he dissected the bird and found the full functionality of the tongue. There were no notes to suggest da Vinci found, asIFOD.comlists:

“When not in use, the woodpecker’s unusually long tongue retracts into the skull and its cartilage-like structure continues past the jaw to wrap around the bird’s head and then curve[s] down to its nostril. In addition to digging out grubs from a tree,the long tongue protects the woodpecker’s brain. When the bird smashes its beak repeatedly into tree bark, the force exerted on its head is ten times what would kill a human.But its bizarre tongue and supporting structure act as a cushion, shielding the brain from shock.”

Brilliant musicians dive deep into sound, acoustics, and how they might manipulate them in a unique manner to serve the song. Writers pay attention to the power of words, as we attempt to hone in on their subtle yet powerful forms of coercion, and the power of the great sentence. Artists, in general, seek to achieve a greater understanding of little relatively inconsequential matters for the expressed purpose of gaining a greater understanding of larger concepts, but a study of the woodpecker’s doesn’t appear to serve any purpose, large or small.

The idea that he was curious about the tongue is fascinating, as it details the full breadth of his sense of curiosity, but it still didn’t appear to serve a purpose. The only answer Walter Isaacson wrote for da Vinci’s relentless curiosity was:

“Leonardo with his acute ability to observe objects in motion knew there was something to be learned from it.”

There is no evidence to suggest that Leonardo da Vinci regretted the idea that he didn’t create more unique paintings, but I would’ve. If I worked as hard as da Vinci obviously did to hone the talent he did, I would regret that I left so few paintings for the historical record. (Though he may have created far more than we know, art experts are only able to definitively declare that da Vinci created 15-20 paintings.) Thus the price we art aficionados pay for da Vinci for stretching himself so thin ( as discussed in Walter Isaacson’s Leonardo da Vinci), is relatively few paintings.

“You could say that,” we might say arguing with ourselves, “but if he wasn’t so relentlessly curious about such a wide range of what we deem insignificant matters, the relatively few works we now know likely wouldn’t have the detailed precision we now know.” If he wasn’t so relentless curious about the particulars of the manner in which water flows, and the effects of light and shadow, the techniques he employed (sfumato andChiaroscuro) might’ve taken future artists hundreds of years to nuance into its final form. Da Vinci did not discover these techniques, but according to the history of art, no one employed them better prior to da Vinci, and the popularity of his works elevated these techniques to influence the world of art.

Arguments lead to arguments. One argument suggests that thirty quality artistic creations define the artist, and the other argument suggests that one or two masterpieces define an artist no matter how many subsequent pieces he puts together. An artist who creates a Mona Lisa or a The Last Supperdoesn’t need to do anything else.I understand and appreciate both arguments, but we can’t fight our hunger for MORE. When we hear the progressions that led to The Beatles “The White Album”, and then we hear “The White Album” we instantly think if those four could’ve kept it together, or Come Together one more time, we could’ve had more. If Roger Avary and Quentin Tarantino didn’t have a falling out after Pulp Fiction, they could’ve created more great movies together? If Franz Kafka could’ve kept it together, and devoted more of his time to writing, it’s possible that Metamorphosis and The Trial wouldn’t be the two of the far too few masterpieces he created.

The rational side of me knows that more is not always more, and that the “Everything connects to everything else” theme we connect to da Vinci’s modus operandi informed the art we now treasure, and I understand that his obsessive pursuit of perfection led to his works being considered the greatest of all time, but I can’t get past the idea that if he wasn’t so distracted by everything that took him away from painting, we all could’ve had so much more. Yet, I reconcile that with the idea that that which made him is that which made him, and he couldn’t just flip that which made him into the “off” position to create more art.

Why did da Vinci pursue such mundane matters? Author Walter Isaacson posits that da Vinci’s talent “May have been connected to growing up with a love of nature while not being overly schooled in received wisdom.” On the subject of received wisdom, or a formal education, da Vinci was “a man without letters”, and he lacked a classical education in Latin or Greek. As with most who rail against those with letters after their name, da Vinci declared himself “a disciple of experience”. He illustrated his self-education by saying, “He who has access to the fountain does not need to go to the water-jar.” He who has access to primary sources, in other words, doesn’t need to learn about it throughthe second-hand knowledge attained in text books. Da Vinci obviously suffered from an inferiority complex in this regard that led him down roads he may not have traveled if his level of intelligence was never challenged. His creative brilliance was recognized and celebrated, as da Vinci knew few peers in the arena of artistic accomplishment. We can guess that his brilliance was recognized so early that it didn’t move his needle much when even the most prestigious voices expressed their appreciation for his works. Yet, the one thing we all know about ourselves is that we focus on our shortcomings, and while we celebrate his intelligent theories and deductions, we can only guess that those with letters behind their name dismissed him initially. “What do you know?” they might have asked the young da Vinci, when he posed an intellectual theory. “You’re just a painter.” Was he dismissed from intellectual discussions in this manner early on in life? Was he relegated-slash-subjugated to the artistic community in his formative years, in a way that grated on him for the rest of his life? Did he spend so much of his time in intellectual pursuits, creating and defeating intellectual boogie men in a manner that fueled a competitive curiosity for the rest of his life?

Even today, we see brilliantly creative artists attempt to prove their intellectual prowess. It’s the ever present, ongoing battle of the left vs. right side of the brain. The brilliant artist’s primary goal in life, once accepted as a brilliant artist is to compensate for his lack of intelligence by either displaying it in their brilliant works of art or diminishing the level of intellect their peers have achieved. Is this what da Vinci was doing when he laid out a motto for all, one he calledSaper vedere(to know how to see). He claimed that there are three different kinds of people, “Those who see by themselves, those who see when someone has shown them and those who do not see.” In this motto, da Vinci claims his method superior, which it is if one counts consulting primary sources for information, but why he felt the need to pound it into our head goes to something of an inferiority complex.

One element that cannot be tossed aside when discussing da Vinci’s relentless curiosity is that he was born into a comfortable lifestyle. The young da Vinci never had to worry about money, food, or housing. As such, he was afforded the luxury of an uncluttered mind. When a young mind doesn’t have to worry about money, food, or achieving an education to provide for himself and his family, he is free to roam the countryside and be curious about that which those with more primary concerns do not have time to pursue. Isaacson’s writing makes clear that although Leonardo da Vinci was an unusual mind on an epic, historical scale, the privilege of thinking about, and obsessing over such matters can only come from one who has an inordinate amount of free time on his hands. Perhaps this was due to his privilege, his comfortable lifestyle, or the idea that he didn’t have much in the way of structured schooling to eat up so much of his thoughts and free time in youth.

Having said that, most modern men and women currently have as much, if not more, free time on their hands, and we could probably compile a list of things we wonder about a thousand bullet points long and never reach the woodpecker’s tongue, the peculiarities of the geese feet, or the jaws of a crocodile to the point that we conduct independent studies or dissections. We also don’t have to do primary research on such matters now, because we have so many “jars of water” that we no longer have the need to go to the fountains to arrive at ouranswers.

Consider me one who has never arrived at an independent discovery when it comes to nature and animals, as I don’t seek primary source answers on them. I, too, am a student of the jaws of water that various mediums, be they documentaries on TV or books, but I am a student of the mind, and I do seek primary source information on the subject of human nature. On this subject, I do not back away from the charge that I’m so curious about it that I exhibit an almost childlike naïveté at times, but reading through Leonardo’s deep dives makes me feel like I’ve been skimming the surface all these years. I mean, who drills that deep? It turns out one of the greatest artists of all time did, and now that we know the multifaceted functions of the woodpecker’s tongue, we can see why he was so fascinated, but what sparked that curiosity? It obviously wasn’t to inform his art, and there is nothing in da Vinci’s bio to suggest that that knowledge was in service of anything. He was just a curious man. He was just a man who seemingly asked questions to just to ask questions, until those questions led him to entries in journals and paintings that we ascribe to the theme everything connects to everything else.