How much money does the average Fortune 500 Company spend learning the mind of the consumer? How many psychologists, linguists, and marketers do their preferred research firms and marketing agencies consult before starting production on a commercial? Their job is to know what makes us laugh, what makes us cry, and what intrigues us long enough to pitch a product or idea. They also have the unenviable chore of finding a way to keep us from fast forwarding through commercials. The average commercial is thirty seconds long, so advertisers need to pack a lot into a tight space. With all the time, money, and information packed into one thirty-second advertisement, one could say that commercials are better than any other medium at informing us where our culture is. One could even go so far to say that each commercial is a short, detailed report on the culture. If that’s true, all one needs to do is watch commercials to know that the art of persuasion has altered dramatically in our post-literate society.

Booksellers argue that we don’t live in a post-literate society, as their quarterly reports indicate that books are selling better than ever. I don’t question their accounting numbers, but some of the commercials big corporations use to move product are so dumbed down and condescending that I wonder if fewer and fewer people are buying more and more books.

When advertisers make their pitch, they go to great pains, financially and otherwise, to display wonderful messages. They then hire a wonderful actor, or spokesman, to be the face of the company. By doing so, of course, the companies who employ the advertising agencies want the consumer to find their company is just as wonderful. If you’re not a wonderful person, their carefully tailored message suggests you can be if you follow their formula. If I am forced, for whatever reason, to watch a commercial, I find their pitches so condescending that they almost make me angry.

Thirty seconds is not a lot of time when it comes to the art of persuasion, so advertising agencies take shortcuts to appeal to us. These shortcuts often involve quick emotional appeals. The problem with this is that people who watch commercials adopt these shortcuts in casual conversations, and they begin using them in everyday life.

I find the quick, emotional appeals these research and marketing firms dig up so appalling that I avoid commercials as much as possible. I find the opposite so appealing, in comparison, that I probably give attempts at fact-based, critical thinking more credit than they deserve. I walk away thinking, “Hey, that’s a good idea!” whether it’s actually a good idea or not, I appreciate the thought they put into making a rational appeal.

Some quick, emotional appeals add crying to their art of persuasion. “Don’t cry,” I say. “Prove your point.” A picture says a thousand words, right? Wrong. We’ve all come to accept the idea that powerful figures and companies require an array of consultants to help them tailor their message for greater appeal. Yet, if one has facts on their side, they shouldn’t need to cry. They shouldn’t need to hire consultants, they shouldn’t need attractive spokesmen, and the idea that they “seem nice and wonderful” shouldn’t matter either. I know it’s too late to put the genie back in the bottle, but I think the art of persuasion should be devoid of superficial and emotional appeal.

***

Marketing firms and their research arms also spend an inordinate amount of time discussing “the future”. Some ads intone their pitch with foreboding tones, and some discuss it with excitement. Our knowledge of the future depends on our knowledge of the past. As evidence of that, we look to our senior citizens. They don’t pay attention to the present, because they find it mostly redundant. “What are you kids talking about these days?” they ask. We inform them. “That’s the same thing we were talking about 50 years ago.” Impossible, we think, we’re talking about the here and now. They can’t possibly understand the present. They can, because it’s not as different from the past as we want to believe. The one element that remains a constant throughout is human nature.

You’re saying that all the change we’ve been fighting for will amount to nothing? It depends on the nature of your fight. Are you fighting to change human nature? If so, there’s an analogy that suggests, if you’re trying to turn a speedboat, all you have to do is flick a wrist. If you’re trying to change the direction of a battleship, however, you should prepare for an arduous, complicated, and slow turn. My bet is that once we work through the squabbles and internecine battles of the next fifty years, the future will not change as much as these doomsayers want it to, and if it does, it will probably be for the better.

***

How many people truly want to create works of art? “I would love to write a book,” is something many people say. How many want it so badly that they’re willing to endure the trial and error involved in the process getting to the core of a unique, organic idea? How many of us know firsthand, what a true artist has to go through? If others knew what they have to go through, I think they would say, “Maybe I don’t want it that badly.”

We prefer quick, emotional appeals. How many overnight geniuses are there? How many artists write one book, one album, or paint one painting to mass appeal? How many of them were able to generate long-term appeal? We should not confuse appeal with best seller. The idea of best seller or attaining market appeal is, to some degree, not up to the artist. They might have a hand in the marketing process, but appeal is largely up to the consumer. The only thing an artist can do is create the best product possible in the large and small ways an artist creates. In this vein, creating art involves a process so arduous that most people would intimidate most.

On the flip side, some say that there are artistic, creative types, and there are the others. There’s no doubt that there are varying levels of talent, but I believe that with enough time and effort most people could create something beautiful and individualistic.

Leonardo da Vinci was a talented artist, who painted some of the greatest pieces of art in world history. From what I’ve read about the man, however, he achieved so much in the arts that it began to bore him. After working through his apprenticeship and establishing himself as one of the finest painters of his day, he received numerous commissions for various works of art from the wealthy people and government officials around him. He turned some down, never started others, and failed to complete a whole lot more. One theory I’ve heard on da Vinci is that if he had a starving artist period, he probably created hundreds of thousands of pieces in that period, but that a vast majority of those pieces were lost, destroyed, or are otherwise lost to history. By the time, he achieved a level of stature where those in his day wanted to preserve his work, painting bored him so much that he created comparatively few pieces. Either that, or in the course of his attempts to create that elusive “perfect piece” da Vinci began studying the sciences to give his works greater authenticity. In the course of those studies, he became more interested in the sciences than he was in painting. These are just theories on why we only have seventeen confirmed pieces from Leonardo da Vinci, but they sound firm to me.

Leonardo da Vinci was a talented artist, who painted some of the greatest pieces of art in world history. From what I’ve read about the man, however, he achieved so much in the arts that it began to bore him. After working through his apprenticeship and establishing himself as one of the finest painters of his day, he received numerous commissions for various works of art from the wealthy people and government officials around him. He turned some down, never started others, and failed to complete a whole lot more. One theory I’ve heard on da Vinci is that if he had a starving artist period, he probably created hundreds of thousands of pieces in that period, but that a vast majority of those pieces were lost, destroyed, or are otherwise lost to history. By the time, he achieved a level of stature where those in his day wanted to preserve his work, painting bored him so much that he created comparatively few pieces. Either that, or in the course of his attempts to create that elusive “perfect piece” da Vinci began studying the sciences to give his works greater authenticity. In the course of those studies, he became more interested in the sciences than he was in painting. These are just theories on why we only have seventeen confirmed pieces from Leonardo da Vinci, but they sound firm to me.

***

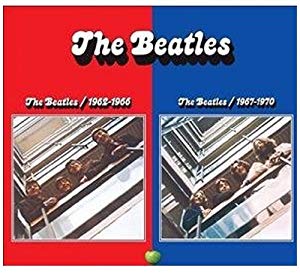

There is a hemispheric divide between creative types and math and science types. One barometer I’ve found to distinguish the two is the Beatles. So many types love the Beatles that we can tell what type of brain we’re dealing with by asking them what Beatles era they prefer. With the obvious distinctions in style, we can break the Beatles down into two distinct eras, the moptop era includes everything they did before Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band, and the “drug-induced” era that followed. Numbers-oriented people generally love the moptop era more, and the creative, more right brain thinkers tend to prefer Sgt. Peppers and everything that followed. The moptop era fans believe the Beatles were a better band during the moptop era, because “they were more popular before Sgt. Peppers. Back then,” they say, “the Beatles were a phenomenon no one could deny.” Moptop era fans often add that, “the Beatles got a little too weird for my taste in the “drug-induced” albums that followed.” Although there is some argument over which album sold the most, at the time of release, it is generally argued that the latter half of their discography actually sold more than the first half. Numbers-oriented people should recognize that the latter albums were bound to sell more if for no other reason than the moptop Beatles built a fan base who would purchase just about anything they created after the moptop era. Those who lived during the era, however, generally think that the Beatles were less controversial and thus more popular during their moptop era, and if you’ve ever entered into this debate you know it’s pointless to argue otherwise. We creative types would never say that the pre-Sgt. Peppers Beatles didn’t have great singles, and Revolver and Rubber Soul were great albums, and we understand that those who lived during the era have personal romantic attachments to their era of Beatles albums, but we can’t understand how they fail to recognize the transcendental brilliance of the latter albums. We think the brilliance and the creativity they displayed on Sgt. Peppers and everything that followed provided a continental divide no one can dispute.

Further evidence of the popularity of the latter half of the Beatles catalog occurred in 1973. In 1973, the Beatles released two greatest hits compilations simultaneously for fans who weren’t aware of the Beatles during their era. The blue greatest hits album, which covered the 1967-1970, post Sgt. Peppers era has sold 17 million to date, while the red greatest hits 1962-1967, moptop-era album has sold 15 million. As anyone who has entered into this debate knows, however, it’s an unwinnable war.