“I’ll never be bored again!” I said the day I purchased my first smartphone. I said that in reference to one of the very few games we play that has no winners: the waiting game. With a smartphone in hand, I thought I could finally resolve one of my biggest complaints about life: waiting.

“We’re not going to live forever,” we complain when someone is involved in the life and death struggles of a grocery store price check. Most of us don’t take out our life expectancy calculator to figure out how long we’re going to live, or to calculate how much of our lives we’ve wasted waiting in line, but we all love sharing that snarky joke about the guy complaining to the clerk that the price tag said asparagus cost $3.47 as opposed to the register’s reading of $3.97.

We’re all waiting for something, all the time, but what makes us angrier, waiting for something to happen, or doing nothing for long stretches of time? We’ve all experienced our frustrations inch their way over into anger, then boil over into rage, and we’ve all experienced that sense of helplessness when it happens to us. With a smartphone in hand, I correctly predicted that I could avoid falling into that trap of claustrophobic silence and inactivity by filling it with something, something to do with my hands, and something is always better than nothing in the waiting game.

We’re all waiting for something, all the time, but what makes us angrier, waiting for something to happen, or doing nothing for long stretches of time? We’ve all experienced our frustrations inch their way over into anger, then boil over into rage, and we’ve all experienced that sense of helplessness when it happens to us. With a smartphone in hand, I correctly predicted that I could avoid falling into that trap of claustrophobic silence and inactivity by filling it with something, something to do with my hands, and something is always better than nothing in the waiting game.

Promptness is About Respect

The waiting game is not selective or discriminatory. Everyone from the most anonymous person on the planet to the most powerful has to wait for something, but there’s waiting and then there’s waiting. The waiting game is all about power and the lack thereof. When we’re stuck in line, at a restaurant, waiting for a seat, we experience a sense of powerlessness. We’re so accustomed to having power over our own life, as adults, that when we find out the wait time for that restaurant is forty-five minutes, we exert that power by walking away. When we find out every decent restaurant in town has a thirty-to-forty-five minute waiting time that sense of frustration sets in, and we eat at home. When someone we love leaves us sitting in that restaurant for a half an hour to forty-five minutes a sense of helplessness creeps in when we realize that we’ve accidentally put ourselves in a position of dependence yet again.

I don’t know if everyone feels this way, but I replay a Madonna quote in my head. “If you have to count on others for a good time, you’re not doing it right.” When I’m sitting in a restaurant with patrons passing me, looking at the vacant side of my table, I realize I’m counting on the wrong people in life, the narcissistic, irresponsible, and disrespectful people I count on for an enjoyable lunch. If they leave us there long enough, by ourselves, we’ll start to dream up all sorts of motives and agendas for their tardiness. That frustration can lead to anger and a level of teeth gritting and grinding that damages the expensive and painful dental work the impatient we’ve had done.

I know that the search for what could tip me over into some form of mental illness is over when I am on the other end of the waiting game, and I eventually hear, “What is the big deal, I was only a couple minutes late, and I had to …” They usually fill that void with utter nonsense that we cannot disprove, so we just let it go.

I know that the search for what could tip me over into some form of mental illness is over when I am on the other end of the waiting game, and I eventually hear, “What is the big deal, I was only a couple minutes late, and I had to …” They usually fill that void with utter nonsense that we cannot disprove, so we just let it go.

Life happens when we least expect it sometimes, and sometimes we’re going to be late. If we respect the other person, we call, text, or email us to inform them we’re going to be late, but that would be respectful on our part. That’s really what we’re talking about here, the respect or lack thereof, on their part. If we respect our employer, we show up on time. If we enjoy the company of someone we’re dating, we show up on time, or early. It’s about respect, the lack thereof, and narcissism. And when they show us this lack of respect, quality friendships can be tainted and temporarily damaged, and dissociations with associates end what could’ve become a friendship. We overreact to such slights, and we know it, but it all boils down to the fact promptness is all about respect.

The Eradication of Boredom

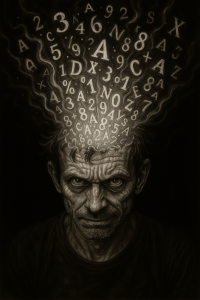

When we’re immersed in the maddening waiting game, the mosquito paradox comes to mind. Anyone who has ever had a beautiful day at the park ruined by a scourge of mosquitoes has asked why scientists don’t find some way to bioengineer an eradication of that relatively useless species? Biologists, with a specialty in mosquitoes, provide arguments for why we shouldn’t, but when we’re swatting, slapping, and running from the scourge, we develop seven counter arguments to every one of theirs. The only vague but true answer we’ll accept is “Anytime we mess with nature, there will be consequences.” We’ve all heard that in relation to the mosquito, but what about waiting and the resultant boredom? Boredom is a naturally occurring event. What could possibly be the consequences of eradicating boredom? We’re not talking about that simple, “I don’t know what to do to pass the time” boredom. We’re talking about levels of boredom that takes us to the edge of an abyss that stares back at us, until it roars to the surface and frightens everyone around us.

When we’re immersed in the maddening waiting game, the mosquito paradox comes to mind. Anyone who has ever had a beautiful day at the park ruined by a scourge of mosquitoes has asked why scientists don’t find some way to bioengineer an eradication of that relatively useless species? Biologists, with a specialty in mosquitoes, provide arguments for why we shouldn’t, but when we’re swatting, slapping, and running from the scourge, we develop seven counter arguments to every one of theirs. The only vague but true answer we’ll accept is “Anytime we mess with nature, there will be consequences.” We’ve all heard that in relation to the mosquito, but what about waiting and the resultant boredom? Boredom is a naturally occurring event. What could possibly be the consequences of eradicating boredom? We’re not talking about that simple, “I don’t know what to do to pass the time” boredom. We’re talking about levels of boredom that takes us to the edge of an abyss that stares back at us, until it roars to the surface and frightens everyone around us.

Some of us loathe the boredom inherent in the waiting game so much that it whispers some scary things about us to us, but when it’s all over, it dawns on us that something happens to us when we spend too much time in claustrophobic silence with nothing to do but think.

How many useless, pointless thoughts have we had in such moments? We flush most of those thoughts out of our mind after it’s over, as we will with that which our body cannot use, but some thoughts collect, mate, and mutate into ideas that we can use. How many of our more meaningful, somewhat productive thoughts had hundreds of useless, pointless parents conjugating during the waiting game?

***

The child and I often talk a lot about how relatively boring things were when I was a kid. This involves me recalling for him what we did for fun, and how we thought those things were so much fun at the time. “We had to do these things,” I say when I see his face crinkle up, “because we were all so bored.” These complaints could be generational, as I often hear the previous generation describe their youth as “Such an incredible time to be a kid,” and they were raised on farms! I’ve been on farms, trapped there for huge chunks of my youth, and the only thing I found incredible about it was how incredibly boring it was. It takes a creative mind, more creative than mine, to believe that being raised on a farm is an “incredible” time.

“It’s all about perspective,” they say, and they’re right. If we don’t know any better, skipping stones in a pond and fishing can be a lot of fun. We rode our bikes around the block a gazillion times, and we thought that was an absolute blast, and then we played every game that involved a ball, but they all seem comparatively boring when compared to the things kids can do now. We could argue all day about the comparisons, but they do have better things to fill the empty spaces. Yet, what happened to us as a result of all those empty spaces, and what happens to them as a result of mostly being devoid of any?

How much of our youth did we spend sitting in chairs, looking out windows, waiting for something to happen? Some of us did something, anything, to pass the time until the event we were waiting for could happen, but there were other times when we just had to sit and wait. We’d sit in those chairs and think up useless and pointless crap that ended up being nothing more than useless and pointless crap, but how many bountiful farm fields require tons of useless and pointless crap per acre?

We have cellphones and smartphones now. That’s our power. That’s how we eradicate boredom. “4.88 billion, or 60.42%, of the world population have cellphones, and the number [was] expected to reach 7.12 billion by the end of 2024. 276.14 million or 81.6% of Americans have cell phones.” We don’t ever have to be bored again.

We have game consoles. “The Pew Research Center reported in 2008 that 97% of youths ages 12 to 17 played some type of video game, and that two-thirds of them played action and adventure games that tend to contain violent content.” These kids may never have to face the kind of boredom I did as a kid. We didn’t even have an Atari 2600 in our home when just about every kid we knew did, and it wasn’t because our dad wanted to prevent us from becoming gamers. He was just too cheap. So, we were forced to do nothing for long stretches of time.

When you’re as bored as we were, the mind provides the only playground. “Is there something on TV?” There never is, and I don’t care how many channels, streaming services, apps, and websites we have, an overwhelming amount of programming is just plain boring to kids. We could go out and play, but when you’re from a locale of unpredictable climates, you learn that that is not possible for large chunks of the year. The only thing we can do, when we’re that bored, is think about things to do. I invented things to do to pass the time, but they could get a little boring too.

Filling the Empty Spaces

“You’re weird,” is something I’ve heard my whole life. I’ve also heard, “I’ve met some really weird fellas in my time, but you take the cake,” more than a few times. That’s what I did when I ran out of things to do. I sat around and got weird. Your first thought might be, “Well, I don’t want to be weird, and I don’t want anyone thinking my kid is weird either.” Understandable, but what is weird? Weird is different, it’s having divergent thoughts that no one has considered before, until they grew as bored as we did. Weird is rarely something that happens overnight. It takes decades of boredom, and it takes a rewind button of the mind, replaying the same thoughts over and over, until we’ve looked at the same situation so many different ways, on so many different days that we’ve developed some weird ideas and abnormal thoughts about people, places and things around us. This is what happens when we stare out windows too long, looking at nothing, wondering how the world might look different if it was weird, strange, or just plain different. It’s what happens when someone lives too long in the mind, and their peeps start worrying that they’re not doing it right.

“You’re weird,” is something I’ve heard my whole life. I’ve also heard, “I’ve met some really weird fellas in my time, but you take the cake,” more than a few times. That’s what I did when I ran out of things to do. I sat around and got weird. Your first thought might be, “Well, I don’t want to be weird, and I don’t want anyone thinking my kid is weird either.” Understandable, but what is weird? Weird is different, it’s having divergent thoughts that no one has considered before, until they grew as bored as we did. Weird is rarely something that happens overnight. It takes decades of boredom, and it takes a rewind button of the mind, replaying the same thoughts over and over, until we’ve looked at the same situation so many different ways, on so many different days that we’ve developed some weird ideas and abnormal thoughts about people, places and things around us. This is what happens when we stare out windows too long, looking at nothing, wondering how the world might look different if it was weird, strange, or just plain different. It’s what happens when someone lives too long in the mind, and their peeps start worrying that they’re not doing it right.

Some weird, strange, and just plain different thoughts led us to think about the difference between success and failure. Success is a short-term game that will mean nothing tomorrow if you’re not able to back it up, so you better enjoy it while it lasts, because if there’s one thing we know about success, it has a million parents and failure is an orphan. We also realize that, in those dark, quiet moments we spend alone, looking out the car window on the drive home, that failure does define us. Athletes and business people say, “Don’t let failure define you,” but it defines us. Some remember those moments, and some will never forget, but what we do shortly after failing will define us too. The thing that plagues us is, “Was that moment of failure an irreversible blemish?” and when we’re left staring out the window at nothing, it can feel like it is. Some will never forget, and we know who they are, because they always remind us who they are, but most forget. As any trained public speaker will inform us, an overwhelming number of people will forgive, forget, and dismiss errors. Most people aren’t paying near as much attention as we think, and most people aren’t dying to see others commit errors. When we’re left alone for long chunks of time, replaying moments over and over, we can make the mistake of thinking it’s the opposite.

“Reach for the stars,” they say. “Become the next Albert Einstein, Vincent van Gogh, Isaac Newton, and Leonardo da Vinci, fill your empty spaces, and reshape your world.” It’s great advice, and we think about how we should try to be better today than we were yesterday, and we shouldn’t spend those dark, quiet moments obsessing about trivial notions we consider our limitations. As we sort through those famous names, we ask how bored were they, when they were kids? Those guys had nothing to do either, when they were kids. They didn’t have movies, TV, devices, or consoles to occupy their time. As boring as it could be to be a kid in our generation, we can only imagine those previous generations were just itching with boredom back in their day, and they were so bored that they dreamed up some things that laid the foundation for everything we find interesting now. We can imagine that most dismissed them as dreamers and daydreamers that wouldn’t amount to much, and they ended up conjugating all of those pointless and useless thoughts into something that ended up reshaping our world.

No matter how much we daydream, or dream up interesting thoughts, most of us will never actually reach those stars. Yet, something happens to us when we’re so bored that we think up weird and interesting thoughts that will never amount to anything. We accidentally, incidentally, or just by the natural course of filling empty spaces become more interesting. Thinking so much that we think too much could lead us to divergent thoughts that some people find so weird, strange and just plain different, but that can lead them to ask us about matters that they consider trivial, relatively unimportant, to important. Our unique perspective often attracts people to us, and it could lead us to have more friends, which could be one of the primary reasons we should consider inserting more boredom into our kids’ lives. Our kids might not know who they are, or who they could be, if they find artificial ways to avoid ever sitting in front of a window with nothing to do but think about everything. Even if they never make it above the lower-to-middle stations in life, they might learn how to make life more interesting, and they might accidentally figure out how to enjoy their lives better, and in the process of being so bored, they might learn how to become happier, more interesting people.