Joggers and those who take regular walks know that they’ll step in something sooner or later. I see historical nuggets in much the same way. When we read and research matters of history, some of it will find its way into the grooves in our shoes and stick and some of it is so old or cold that it just falls off. That being said, I don’t think a display of nugget knowledge is a display of intelligence, but a byproduct of interest. Those who are fans of the show Friends, or Jennifer Aniston, could probably tell me a number of interesting little nuggets that might shock me. I happen to be interested in the history of the United States through its presidents, and the following is a list of the nuggets that have stuck through the years. I’ve known these little nuggets for so long that I assume everyone knows them, but when I provide the big reveal, the reactions. They either think I’m a huge nerd, a vat of useless knowledge, or an interesting conversationalist. I add the latter as a narcissistic possibility, but I’ve rarely seen evidence of it on my audience’s faces. They usually pause politely and carry on the conversation I interrupted as if I didn’t say anything.

“Tippy canoe and Tyler too,” my great-aunt sang for no reason.

“What is that?” I asked her.

“It’s a saying,” she said. “I don’t know where it came from, and I don’t think anyone does. It’s just something to hum.”

My great-aunt was old when she sang that, and I was accustomed to old people knowing everything about everything, but she didn’t know the origin of a song she sang all the time.

Decades later, I learned that Tippy Canoe and Tyler too was a song used to influence the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison and vice-presidential candidate John Tyler. They nicknamed William Henry Harrison Tippecanoe, because he led the forces that defeated Tecumseh on the Tippecanoe River, and John Tyler was the other guy on the ticket, the candidate for vice-president, or the “too”.

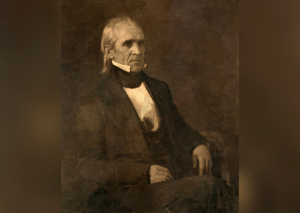

Though one of the country’s shortest presidents at 5’8″, Polk accomplished the “no small feat” of annexing Texas, New Mexico, Oregon, and California. Polk was instrumental in acquiring more than 800,000 square miles and expanding the country by roughly one-third.

Presidential candidate Polk won his election by pledging to reduce tariffs, reform the national banking system, expand the country, and that he would accomplish all that in four years. He pledged he would not run for reelection.

Polk was one of the few presidents to accomplish all of his core pledges while in office, and he accomplished the latter after his term ended, and he did not submit for reelection. While in office, Polk was well-known as a workaholic, working to accomplish all of his campaign pledges. Some suggest that he worked so hard, and for so many hours, that his four years in the White House wore him out. He died months after leaving office of cholera on 15 June 1849 at the young age of fifty-three.

James Knox Polk is rarely listed among the great presidents by non-historians. Historians often list him in the upper half, some list him in the upper third. He gets high marks for crisis leadership and administrative skills, but he fails in other areas, according to historians. Yet, he often gets lumped in with the relatively forgettable presidents that took office after Andrew Jackson and before Abraham Lincoln.

Theodore Roosevelt

Needless to say, campaign speeches are vital to every presidential campaign. With modern technology, a presidential candidate can deliver speeches in his basement, but candidates did not have such luxuries in 1912. The only way, save for print, for a candidate to deliver his message, display his charisma, and woo prospective voters, was to take a train, or whatever lesser mode of transportation they could find, to stop in various locales and speak directly to voters. The various campaign speeches a candidate delivered across large and small pockets of the nation were sink or swim for him.

Needless to say, campaign speeches are vital to every presidential campaign. With modern technology, a presidential candidate can deliver speeches in his basement, but candidates did not have such luxuries in 1912. The only way, save for print, for a candidate to deliver his message, display his charisma, and woo prospective voters, was to take a train, or whatever lesser mode of transportation they could find, to stop in various locales and speak directly to voters. The various campaign speeches a candidate delivered across large and small pockets of the nation were sink or swim for him.

That said, we can bet that candidates toughed it out through a case of a sore throat, a flu, and other, more severe illnesses or minor broken bones to speak to the public. As tough as those candidates needed to be, I don’t think voters was prepared for:

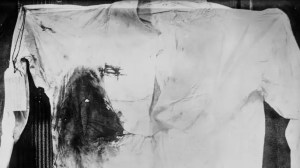

“I don’t know whether you fully understand that I have just been shot,” Theodore Roosevelt informed an audience in Milwaukee, after asking for silence. To confirm what he was saying, Roosevelt unbuttoned his vest to reveal his bloodstained shirt. “But it takes more than that to kill a bull moose.”

To reassure them that he was able to deliver the speech, he said, “Fortunately I had my [50 page] manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet—there is where the bullet went through—and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.”

To reassure them that he was able to deliver the speech, he said, “Fortunately I had my [50 page] manuscript, so you see I was going to make a long speech, and there is a bullet—there is where the bullet went through—and it probably saved me from it going into my heart. The bullet is in me now, so I cannot make a very long speech, but I will try my best.”

As History.com furthers, the projectile had been slowed by his dense overcoat, steel-reinforced eyeglass case and the hefty speech squeezed into his inner right jacket pocket.

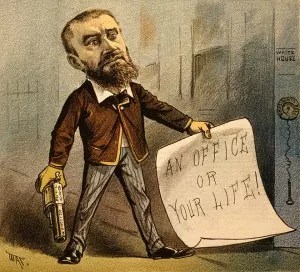

The unsuccessful assassin, “John Schrank, [was] an unemployed New York City saloonkeeper who had stalked [Roosevelt] around the country for weeks. A handwritten screed found in his pockets reflected the troubled thoughts of a paranoid schizophrenic. “To the people of the United States,” Schrank [wrote]. “In a dream, I saw President McKinley sit up in his coffin pointing at a man in a monk’s attire in whom I recognized Theodore Roosevelt. The dead president said—This is my murderer—avenge my death.” Schrank also claimed he acted to defend the two-term tradition of American presidents. “I did not intend to kill the citizen Roosevelt,” the shooter said at his trial. “I intended to kill Theodore

Roosevelt, the third termer.” Schrank pled guilty, was determined to be insane and was confined for life in a Wisconsin state asylum.

Roosevelt tried to use the story of the assassination attempt to secure a third term as president. He did so as a third-party Progressive candidate that they nicknamed “The Bull Moose Party”. He was successful in splitting the Republican vote, squashing his frenemy, William Howard Taft’s reelection bid, but all his efforts did, in reality, was allow one of the worst presidents to ever sit in Washington D.C. to take office Woodrow Wilson.

James Garfield

As with presidents William Henry Harrison, Warren Harding, and to a lesser degree John Kennedy and Abraham Lincoln, Garfield’s tenure as president is better known for his death than his tenure in office, as he was assassinated while in office. Some historians say that this is one of the biggest tragedies in U.S. History, because Garfield’s potential to be one of the presidents on the Mt. Rushmore creation (that occurred much later), is high. Due to the assassin’s bullet, and his doctors historical ineptitude, James Garfield served a mere six months in office, and historians say he was only in peak form for three-to-four of those six months.

A self-avowed communist named Charles Guiteau shot President Garfield, claiming “I am a Stalwart and [Vice-president Chester A.] Arthur is president now!”

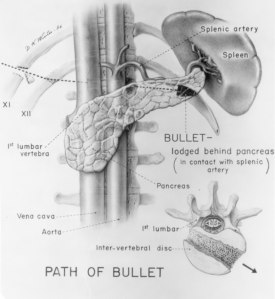

History.com notes, “Doctors were unable to locate the bullet in [Garfield’s] back. Even inventor Alexander Graham Bell (1847-1922) tried–unsuccessfully–to find the bullet with a metal detector he designed.” Medical professionals would later say that if Garfield’s doctors simply left the bullet in Garfield’s body, as they later would with Theodore Roosevelt, Garfield’s chances of survival would’ve greatly increased. On September 19, 1881 — 79 days after the shooting — President Garfield died of a ruptured splenic artery aneurysm due to sepsis and pneumonia. It is believed that Garfield probably would have survived his wounds had he been treated properly.

This was well-known at the time, as evidenced by Charles Guiteau’s attempts to avoid a death sentence, saying, “I did not kill Garfield after all, his doctors did. I just shot him.” As the Crime Museum notes, Guiteau’s bid was unsuccessful, and he was executed on June 30, 1882, less than a year after the shooting. This defeat did not depress Guiteau however, as he danced to the gallows and recited a poem, before waving to the crowd, and shaking hands with the executioner.

***

Charles Dickens provided the best line to describe the present state of the human being, “It was the best of times. It was the worst of times.” How can both exist at the same time? It can’t, but it does, in the present. In the present, you might sing “I got to admit it’s getting better, a little better all the time,” but you can always find someone who sings the, “It can’t get no worse,” part of the refrain.

If you’ve ever discussed the issues of the day with your grandpa, you’ve heard him say something along the lines of, “That’s exactly what we were obsessed with when I was younger. Let me guess, fall of the Republic? Most divisive issue of our day? Yep, yep, that’s exactly what we said.” If you’ve ever discussed the wonderful advancements your generation has made with him, he’s probably said something along the lines of, “Well, when you don’t know the difference, you find a way.” You walk away thinking the good times and the bad times are probably a bunch of hype that you bought into.

Pick the issue, and you’ll hear people take conflicting opinions sometimes in the same sentence, “The technological advancements we’ve made in the present are greater, by leaps and bounds, but I worry about AI.” The same conflicting opinions revolving around the nature of presidential elections we’ve had, occurred some 200 years prior in 1825. Our present suggests it couldn’t get much worse, and that the Founders messed up presidential elections by creating this device called the Electoral College. The 1825 presidential election between Jackson and Adams occurred while most of them were still alive, thirty-seven years after The Constitution was verified, and other than a brief entry by Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 68, that discusses the virtues of popular will, I find no letters that state anything specific about the errors of the Electoral College. They probably didn’t love the idea, but they compromised to make sure smaller states felt greater representation in the decision of their leader. Remember, the Founders were overly sensitive to cries of lack of representation after they were denied it by the monarchy. This lack of representation and the mess that followed in the Jackson v Adams presidential election of 1825 happened in their lifetime, and they probably saw the elements of their Constitutional solutions as the lesser of two evils.

Andrew Jackson V. John Quincy Adams

In 1824, the nation was just coming out of the “Era of Good Feelings” after James Monroe (1817-1825) led an era of peace in the aftermath of War of 1812, and he led the country to a period of true strength, unity of purpose, and one-party government, after the death of Alexander Hamilton and his ideas of Federalism.

In 1824, the nation was just coming out of the “Era of Good Feelings” after James Monroe (1817-1825) led an era of peace in the aftermath of War of 1812, and he led the country to a period of true strength, unity of purpose, and one-party government, after the death of Alexander Hamilton and his ideas of Federalism.

Those good feelings of unity ended quickly in the ensuing 1825 election race between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson. The country appeared as divided as its ever been with Andrew Jackson winning a plurality, but not a majority, of either the popular and the electoral votes. This election pushed the country into its first dispute between the Electoral College and the popular vote, as neither Jackson nor Quincy Adams accumulated the plurality of votes needed to secure the 1825 presidential election. As Tara Ross reports, this election was between Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Secretary of the Treasury William Harris Crawford, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, and Tennessee Senator Andrew Jackson. This conflict resulted in the first time in the young Republic’s history that no presidential candidate secured enough Electoral votes, so, as the 12th Amendment dictated, it was on the House of Representatives to elect the president.

The House of Representatives were given three options: Adams, Jackson, or Crawford. The Constitutional provision did not allow Henry Clay to be considered because he placed fourth.

The latter note proved crucial to the final outcome allegedly, because knowing that he had no avenue for victory, Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House, allegedly entered into a “corrupt bargain” with John Quincy Adams. The “corrupt bargain”, as Jackson supporters theorized, was that Clay met privately a month before the House vote. In that private meeting, Jackson and his supporters allege that Clay informed Adams that he would throw his powerful support, as Speaker of the House to Adams if Adams would use the victory to later nominate Clay to a cabinet position. Adams, for his part, denied the allegation, but Clay’s support gave Adams the 13 House votes Adams needed to secure the presidential election.

Jackson conceded to the peaceful transition initially, until Clay was nominated to arguably the most prestigious position in the cabinet, Secretary of State, three days later. Jackson, and his supporters viewed that appointment as proof that a “corrupt bargain” had been made.

Adding fuel to the fire, reports later emerged that Clay initially tried to strike a deal with Jackson, but Jackson refused to “go to that chair” except “with clean hands.” Had Adams taken a deal when Jackson would not? As with modern politics, Adams never admitted to anything, and no reporters in the era ever uncovered a truth or any evidence that would incriminate or absolve Adams. Hence, even with 200 years of hindsight, “We shall probably never know whether there was a ‘corrupt bargain,’” historian Paul Johnson concludes. “Most likely not. But most Americans thought so. And the phrase made a superb slogan [in the 1828 Jackson v Adams rematch].”

Some allege that this idea of a “corrupt bargain” not only cost Quincy Adams his reelection in the 1828 rematch with Andrew Jackson, but it severely damaged the future political career of Henry Clay too. In this era, the Secretary of State was viewed as a natural stepping stone for the presidency, as four of the seven previous Secretaries eventually sat in the highest office in the land. Clay’s resume not only listed House Speaker and Secretary of State, he was a Congressman, and a Senator before rising to prominence. He helped found both the National Republican Party and the Whig Party. He was well-known as the “Great Compromiser” and was part of the “Great Triumvirate” of Congressmen. He also received Electoral votes for president before the 1825 election. On his resume alone, Clay was a could’ve been should’ve been who never was president. He would rue the day he accepted the Adam’s appointment, because whether it was true or not, the charge of the “corrupt bargain” stuck to him throughout his political career.

Some allege that this idea of a “corrupt bargain” not only cost Quincy Adams his reelection in the 1828 rematch with Andrew Jackson, but it severely damaged the future political career of Henry Clay too. In this era, the Secretary of State was viewed as a natural stepping stone for the presidency, as four of the seven previous Secretaries eventually sat in the highest office in the land. Clay’s resume not only listed House Speaker and Secretary of State, he was a Congressman, and a Senator before rising to prominence. He helped found both the National Republican Party and the Whig Party. He was well-known as the “Great Compromiser” and was part of the “Great Triumvirate” of Congressmen. He also received Electoral votes for president before the 1825 election. On his resume alone, Clay was a could’ve been should’ve been who never was president. He would rue the day he accepted the Adam’s appointment, because whether it was true or not, the charge of the “corrupt bargain” stuck to him throughout his political career.

If you’re as interested in U.S. History through relatively obscure presidents as I am, read Obscure Presidents part I