“Be nice,” is the advice we should give anyone accused of being crazy. “Be nice and smile a lot,” we would add. Someone, somewhere might say, “She’s crazy,” but they usually don’t mean it. By jumping past all of the progressions we have for casually noting that someone might be a little off, we’re trying to be provocative when we joke and say someone is crazy, and provocative is funny. They might start out at weird, followed by strange, a little nutty, a little off, and just plain different, but most people won’t make the leap to crazy in a serious manner. So, when our peers start putting their opinions together about us, “Be nice and smile a lot.”

This doesn’t sound like an adequate defense to such a malleable charge, but if someone accuses us of being crazy there’s probably not much we can do to change their mind. This defense acknowledges that by suggesting we convince those who surround us that we’re kind, and we genuinely care about them. By doing so, we might gather some loyal defenders who will form a team that mount a unified defense against any and all accusers, until our accusers begin to think they’re in the minority.

Most of us have never had anyone seriously question our sanity. They might say things like, “You’re crazy,” or “You’re insane,” but they often say that with a wink and a nod. To those who have seriously been accused of being so far outside the mainframe that it has diminished their quality of life, we offer this advice because we’ve witnessed others rush to the defense of a person they consider nice, regardless what anyone else says. These defenders are prone to dismiss most eccentricities of the nice and kind as endearing qualities. As these eccentricities begin to build up, people will talk. They will share stories and compare notes, but again, if the subject of this scrutiny is considered nice, sweet, or genuinely cares about those around them, their defenders will fight for the accused.

One of the primary components of selling this nice façade is a warm, pleasant smile. A genuine smile not only speaks of peace of mind, it disarms observers searching for cracks in our foundation, and it might serve us well in our attempts to conceal our eccentricities. Anyone who has seriously been accused of being crazy might be surprised to learn just how disarming a simple, warm smile can be. “You think she’s crazy?” observers might say in the face of another’s accusations, “because I think she’s nice.”

“And you’re basing that on what? Her smile?” the accusers counter. “Because Ted Bundy had a pretty, radiant smile. Do you think he was normal?” It doesn’t matter, for the idea that a crazy person seems nice, based on nothing more than a warm, glowing smile is the primary point and the end of the discussion for them.

Another key plank to insert in your fight is to show concern for others. If you find out, through the grapevine, that your worst accuser’s grandmother is sick, take a moment out of your day to ask her about her about it. “Hey, how’s your grandmother doing today?” This will touch her in a way from which she might never recover. If you do it right, and your concern is genuine, your greatest accuser might end up your greatest defender.

We have bullet points that we seek when trying to spot crazy people. It’s a self-defense mechanism we use to protect ourselves in the dark, wild, and sometimes savage environs of the average workplace. Are these bullet points fair? It doesn’t matter. We have created them to help us avoid saying, or doing, the wrong thing to the wrong person who might go crazy on us, and one of the most prominent bullet points we look for is nastiness.

Being nasty is the subject’s best defense mechanism. Most of us don’t choose to be nasty, but we’ve been attacked so many times over the years that we’re defensive when we meet new people. Attack before being attacked is the go-to some have to protect their vulnerabilities. They’ve become so accustomed to being attacked over the years that being nasty is the first arrow they reach for in their quiver. The goal of this preemptive attack is to convince others to avoid them. That could lead to them missing out on some quality workplace relationships, and even some friendships, but most crazy people have not found a better alternative to avoid being attacked. The problem with this strategy is that they might find otherwise sympathetic souls joining in on the discussions of our unpredictability, until they reach an agreed upon characterization that we do not expect.

“You’re telling me to be nice, and smile, and say nice things to these awful people?” crazy people ask us. “Do you have any idea what these awful people have said to me? Has anyone ever accused you of being crazy before? If not, you have no idea what we go through.”

We’re not saying this solution is foolproof, but we saw it. We were there, and we saw the accused do the worst possible thing she could’ve done. Our solution is so simple that most crazy people don’t consider it a viable solution. “Be nice and smile a lot,” we say. If Abbie Reinhold tried it, I have to think it would’ve disarmed most of her accusers.

“When you’re a stranger

Faces look ugly

When you’re alone.”Jim Morrison and Robbie Krieger

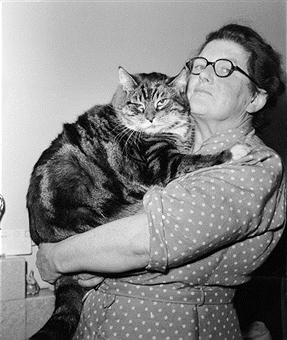

I used to work for an online company. This company rewarded its employees with a month long sabbatical for tenured service. While I was on this sabbatical, my department hired a number of new people. One of them was a crazy person named Abbie Reinhold. One of the first things Abbie did, to introduce herself to the group, was defeat any impressions we might have about her. This preemptive attack involved a confrontation approach to anyone who might challenge the impressions she may have made. Her defense gained her a reputation, however unfair, of being a cat lady.

To this point, no one knew if Abbie Reinhold owned a cat. She simply fit the stereotype, arrow for arrow, bullet point for bullet point. We joked that Abbie could’ve been the prototype for the cat lady on the television show The Simpsons. The stereotype is an affixed staple in our culture, because there are examples of it. It’s not true that all women who own cats are crazy, of course, for we’ve all met perfectly sane women who have an inordinate number of cats as companions. We’ve also encountered women who scream at these cats, as if they’re human, and they find that they get along a lot better with cats than they do humans for all of the psychological underpinnings that are indigenous to a cat lady.

When I arrived back at work, after my sabbatical, I found that those in charge of making seating arrangements placed an Abbie Reinhold across from me, in a cubicle I faced. Did I know that Abbie Reinhold was a little crazy? How could one not sense that something was off about her, based on her preemptive attacks?

My attempts at building a psychological profile on someone, based on first impressions, had been so wrong, so often, at that point in my life that I decided to give Abbie Reinhold a chance. Mary, one of the precedents for how wrong I can be, sat right next to Abbie Reinhold. I was so wrong about Mary that I decided Abbie Reinhold might be another Mary. Mary was a woman of solitude, and a little “off”, but it turned out that Mary was a happy person who was so nice. She had an ever-present smile on her face, and she was always asking about my dad. Mary, it turned out, was such a sweet woman in all other matters that she became anecdotal evidence for how wrong the psychological profiles we build can be.

As that first day wore on, I noticed that Abbie talked to herself a lot, and while I do deem those who talk to themselves a lot a little crazy, I cut all new employees a little slack. Some of the cases we worked on for this company, could be quite difficult, overwhelming, and stressful, and I had firsthand knowledge of how difficult and overwhelming the job could be for a new person. For this reason, I paid little attention to Abbie Reinhold on that first day.

On the second day, Abbie Reinhold began talking to herself when I sat down at 8:00 A.M. up and to the point when she left at 5:30. Man, I thought, this poor woman is really struggling. Abbie’s frustrations were on display for all to see, but as I said I empathized. We all have coping mechanisms for dealing with the stress and pressure of the job, and we all know that coping mechanisms can vary, and they are often unique to the person. If this woman’s coping mechanism included talking to herself, who was I to judge? She did talk to herself a lot though.

The third day was something altogether different. The coping mechanism of talking her way through a case progressed to silent screaming. Abbie developed the habit of silently screaming at her computer. Everything about her face and mouth suggested she was screaming, except for the sound. Her head was bopping, and she bared her teeth. I glanced around to determine the source of her frustration. I couldn’t find anything. She was new though, and I continued to offer her some slack, but the progression didn’t ebb and flow in the manner it had in the past days. Abbie’s frustrations had progressed. Matters, such as these, don’t usually phase me. I’m a calm and levelheaded guy, but I had one foot pointed to the door in case her frustration reached an ultimate resolution.

I worked in various computer companies for nearly a decade at that point, and I saw so many anomalies of human behavior that her idiosyncratic behaviors were noteworthy. Nothing more and nothing less. Did those of us around her laugh when she laughed for no apparent reason, we did. Did we share raised eyebrows when some noises escaped her otherwise silent screams, we did. Those who might call us out for those judgmental reactions have to understand that it’s human nature to laugh at something we don’t understand. When we witness what we consider a confusing anomaly, our impulsive reaction is to either laugh or cry, and I wasn’t so afraid of her that I would cry. I came close the next day, when I saw her eat a cookie, as everything about that act appeared to crystallize the notions I had that she might be crazy.

I would never go so far as to say that I’m a macho man who fears nothing, but I can say without fear of rebuttal, that I’ve never experienced anything resembling fear watching another person eat a cookie. I don’t think I feared her, in the truest sense of the word, but watching her eat that cookie gave me goosebumps.

Some have theorized that goosebumps are a physiological phenomenon that we inherited from our animal ancestors. They’re useless to us now, because most of us don’t have a coat of hair, but the reason we have them, some guess, is that our ancestors either used the elevations in the skin and hair to protect themselves against the cold or to make themselves appear larger when confronted by a potential predator. I didn’t consider Abbie Reinhold’s ravenous consumption of the cookie an act of predation, but the biological phenomenon occurring on my arm suggested that my brain was telling my body that we might want to consider appearing larger just in case.

I assumed she was diabetic, as I have known many diabetics who were calmed by a cookie. I don’t know if that was the case with her, but she ate that cookie in the manner I suspect one would after starving themselves for days.

I watched every bite she took. I don’t know what I was waiting to see, but I was watching. Watching is probably the wrong word to describe what I was doing, for I was not looking at her. By the time Abbie Reinhold began eating the cookie, she established a set of rules that I was not to talk to her, refer to her in anyway, or look at her. I trained myself to pay attention to her, without looking. I was looking at my computer, but I wasn’t typing or doing anything work-related. I was staring at her without looking. When she finished that cookie without any progressions, I did not sigh, but I was relieved.

In the days that followed, I would see her progress from talking to herself, to silently screaming at her computer, to laughing. Most people, who have never been hired to work on a computer ten hours a day, four days a week, have no idea the level of solitude we experience. The employee knows they were hired to work cases in the company’s queues. They know that they are not there to socialize, and they learn to keep non-work-related, social interactions to a minimum. They learn to avoid the temptation of “So, how’s your day going?” because that can lead to a minutes long conversation that might be documented somewhere. I write this to inform the reader who has never worked in an office, with miles of cubicles, that a ten-hour day, sitting behind a computer, can lead to the mind drifting.

Those of us who worked in the service industry dreamed of the day when we didn’t have to interact with people, because some people are bitter and angry about whatever life did to them, and they vent their frustrations on whomever happens to be standing in front of them at the time. Once we achieved that complete overhaul from too much human contact to none, we realized how much we needed it. To satisfy this need, we can accidentally drift back to the rude thing the supermarket checker said to us the other day, and we conjure up a perfect comeback while staring at our computer. We remember the hilarious thing our friend said to us at the bar over the weekend, and we think up the perfect addition to their joke. This can lead to spontaneous and embarrassing emotional outbursts such as laughter. When it happens, we stop as quick as we can, drop the expression and scan our surroundings to make sure no one saw any of it. This woman didn’t seem to care about any of that. Her conversations with no one turned into silent, uproarious laughter, her grimaces turned into silent, vehement screams, and she didn’t catch herself in the midst of these reactions, and she didn’t look around to make sure no one saw them.

In the professional climate of office workers reading the words on their computers, the white noise of the sounds of typing, can lull employees into a safe harbor of the mind. Anything and everything is distracting. Drop a pencil on the carpet, and six people might turn to watch you pick it up. In this climate of solitude and servitude, whispers are distracting and annoying. The relatively benign sounds of soft laughter can lead the bored to roll over to see what you’re laughing at on your computer. In the early days of Abbie Reinhold’s tenure on our team, some employees would roll over to her desk to see why she was laughing. After a number of these incidents, fewer and fewer rolled over to Abbie’s desk to see what caused her emotional displays. We would laugh, but it was a laugh of empathy, for we knew how often we drifted into our own daydreams. We managed to restrain ourselves from displays of emotion, but we knew how close to that line we were. Over the course of our brief tenure together, Abbie shattered the shackles of embarrassment by reenacting scenes from her life without shame. When a non-team member would stop by our desk to ask us a question, and they would see her turning left and right with laughter or anger, they would ask us about it, and we would say, “Just ignore it.” On one such occasion, she placed a hand between her breasts and apologized to her computer screen for laughing so hard. She wasn’t speaking to me, the unfortunate witness to her activities. She wasn’t speaking to anyone.

When Abbie Reinhold talks to herself, she gesticulates in a casual manner that one uses to expound upon meaning. These gesticulations progress to a flailing of the arms, in a manner reserved for partygoers having one hell of a good time. She swirls in her computer chair, in a Julie Andrews, The Hills are Alive manner, when she appears immersed in a wonderful moment in her life, and she says mumbles responses to the fictional characters who surround her.

I wondered one day if she is talking to people in the future or the past, or is she one of those rare individuals who –like a Kurt Vonnegut character– is unstuck in time, and is living in the past, the present and the future at the same time?

I wondered what Abbie Reinhold would think of me if I started talking to myself, followed by silent screams, uproarious laughter and wild gesticulations. Would she laugh from a distance at my bizarre actions, to reveal how oblivious she is to her own? Would Abbie laugh at me with full knowledge of her actions, but by ridiculing me, she hoped to gain some distance from the things that crazy people do? Would she view my bizarre display as an opportunity in which she could define herself to others, thus lifting herself above those who engage in such activities for the purpose of either changing the minds of those around her, or vindicating her beliefs in her own sanity? The unlikely alternative, I suspect, is that she would see what I was doing and identify with in a manner that might establish some sort of solidarity between us. Even if I mimicked her without any discernible form of mockery, I doubt that she would defend me against anyone who ridiculed me for talking to myself. I doubt she would say anything along the lines of, “Hey, I talk to myself, how dare you crack on my people.” I doubt that she was that objective.

On one of the days that followed, Abbie Reinhold stood. She was not looking at a fellow employee named Natalie, but she wasn’t looking away either. She was just standing. She did stand near enough to Natalie that Natalie thought Abby had a work-related question that she couldn’t figure out a way to articulate. Natalie was a senior agent on the team, assigned to answering agent questions.

“What’s up?” Natalie asked her.

“Just stretching,” the crazy lady said.

“What’s wrong with that?” I asked when Natalie informed me of that brief conversation.

“She was standing still,” Natalie informed me. “I don’t think she moved a muscle.”

“Did you ask her what muscles she was stretching?”

Abbie Reinhold also eats her earwax. She pulls it out, examines it, and she eats it on occasion. Some of the times, Abbie Reinhold looks at it and discards it. I often wonder what her selection process involves. What’s the difference between a good pull, and a bad one?

I wondered if I cracked a joke about people who eat their own earwax, what Abbie’s reaction would be. Would she laugh from a distance at such foolish people, or would she defend her fellow earwax eaters? “Hey, I eat my ear wax, how dare you crack on my people.”

“When you’re strange

Faces come out of the rain

When you’re strange

No one remembers your name.”

Jim Morrison & Robbie Krieger

Some readers might find this piece mean-spirited, as we should never discuss (much less laugh at) those who have vulnerabilities. To those charges, I submit to the court of public opinion, exhibit A: Abbie Reinhold.

As much as we might want to defend Abbie Reinhold, she was not a sympathetic figure, and witnesses to Abbie Reinhold’s demeanor would testify to the fact that Abbie Reinhold could often be witnessed laughing as hard, if not harder, at the idiosyncrasies of those around her as anyone else. (This raucous laughter might have been born of the relief of being on the other side of that laughter.) We understood that she was defensive by nature when we met, but she began leveling attacks against us before we knew her last name. We have no knowledge of the frustrations that drove her to attack us, and we empathize with anyone who has been attacked for their characteristics, for we have all experienced such attacks throughout our lives.

When it comes to using past grievances to fuel nastiness, anything can provide an impetus. Perhaps she made unfair associations that led her to unfair conclusions about us, but we were ambivalent to her presence, until she attacked us with her shield. Abbie Reinhold brought her past grievances to the table not us. We did not seek to chastise, or ostracize, Abbie Reinhold. We viewed her as nothing more than another employee in a large company, until she made her presence known.

For those in the court of public opinion who are not willing to take some anonymous author’s word for it, we submit exhibit B: Sheila Jones. Sheila Jones was what we might consider the prototype for a nice, sweet, woman who has lived long enough, and experienced just enough, to know the best and worst of humanity. Sheila is the type of person who chooses to view humanity from the magnanimous position of believing that her waste matter stinks too. 99 times out of 100, Sheila was uncomfortable talking about other people, and conversations about another’s vulnerabilities made her so uncomfortable that she tried to end them as patiently and politely as she could. She knew this is what we all do, but they made her uncomfortable. Not only was Sheila an audience to the stories we told about Abbie Reinhold, she broke the mold we had for her by contributing to them.

I make no claim to being as nice and understanding as Sheila was, is, and always will be. She is one of those rare individuals who are nice, understanding, and empathetic to the plight of the 99.9 percent of the population. When the subject of Abbie Reinhold arose, not only did Sheila join the pack of hyenas, ripping at the carcass, she laughed as hard as any of us did, even if it was behind a hand.

The question I have, now that I have achieved enough distance from this story to have some objectivity on it, is would anyone like Sheila want to trade such stories about Abbie Reinhold if Abbie was a genuinely nice person who wore a hearty smile on her face, regardless what she’d experienced? Would anyone as nice as Sheila laugh as hard as she did, if Abbie Reinhold was a sweet person who just happened to have been afflicted with some noteworthy eccentricities? The males might have, for males are predisposed to enjoying stories that pertain to the weaknesses and frailties of another, a trait that we can trace to their king of the hill mentalities. Mean girls might have too, for many of the same reasons. We’ve all heard of people raised with Midwest values and Southern hospitality. Sheila had all that, plus a personal level of sympathy for others that those of us who knew her considered unmatched. Thus, those of us who know Sheila know that if Abbie was anything from ambivalent-to-nice to Sheila Jones, she would have shut down any discussions about the woman’s eccentricities with a simple word about decorum and being nice. If Abbie was a nice person who just happened to do odd things, the nice women in our group would’ve followed Sheila’s lead in shaming us against engaging in such discussions. “She’s a nice person,” is something she and all the nice women in our group would have said, and they would’ve dismissed every characterization of Abbie Reinhold on that basis. The fact that these women not only laughed uproariously at the stories of Abbie Reinhold’s idiosyncrasies, but shared their own experiences with her, and drove the discussion in many cases, should suggest to any people seeking to proactively diffuse any attempts at characterizing them in an unfair and exaggerated manner, that the best way to ingratiate themselves to those who might end up defending them, is to simply be nice and smile a lot.