“I have nothing to complain about!” Melissa yelled as if volume made her grievance more grievous. She was employing irony, and she was winning! Complaining is what Melissa did. It’s what we all did, and if you wanted in you had to learn how to complain about something, even if that something involved the crushing burden of having nothing to complain about.

Our complaints often had something to do with the inhuman monolithic corporation we worked for that didn’t pay us enough, offer us enough benefits, or care that we were trapped behind a computer for ten hours a day, four days a week. Those of us in the inner circle of our inner circle learned to cycle out and complain about everything. There was no regular menu of complaints from which to choose, and there were no specials of the day. Complaining was just what we did.

“Complaints are like orifices,” Brian said to try to ingratiate himself with the group, through ironic, observational humor that matched Melissa’s. “Everyone’s got them, but we complain about not having more.” Unfortunate to Brian’s legacy, his little joke didn’t land, because we had an unspoken rule that we don’t complain about complainers, until we’re complaining about their constant complaints behind their backs.

Complaining is such a vital component of our being that it’s just something we do. We complain about how bored we are in the beginning, we complain about school, the workplace, and in our final decades on Earth, we complain about our lack of health, until it goes away.

If there is an afterlife, and we are introduced to absolute, unquestionable paradise, we will probably be blown away by it, initially, but we’ll get used to it after a while, and we’ll find something to complain about. “Have you noticed that they provide Black Duck umbrella picks for our cocktails here? I hate to complain, but it’s just such a huge step down from the OGGI cocktail umbrellas to which I was accustomed.”

If there is an afterlife, and we are introduced to absolute, unquestionable paradise, we will probably be blown away by it, initially, but we’ll get used to it after a while, and we’ll find something to complain about. “Have you noticed that they provide Black Duck umbrella picks for our cocktails here? I hate to complain, but it’s just such a huge step down from the OGGI cocktail umbrellas to which I was accustomed.”

If we have nothing to complain about, our brain will make something up just to justify its existence.

How often do we think just to avoid boredom, and thinking about how to complain about something is far more interesting than realizing how good we have it. Thinking about how good we have it kind of defeats the whole purpose of thinking.

“That sounds like first world thinking.” It is, but I’m guessing that there are plenty of third-world citizens who complain about stupid stuff too.

***

My friends’ parents enjoyed complained about the state’s college football team, until the team started winning. At that point, they complained about having nothing to complain about. I didn’t realize it at the time, but we were all complaining about a college football team that proved to be one of the most successful programs for that span of time. Our complaint was that our team didn’t win the national championship every year.

His parents did this, my dad did it, and we all grew up complaining about it. “We were so close!” we’d complain. “I’d rather finish 0-fer than get that close again,” was our common complaint. Their complaints were so unrealistic they were funny. I laughed at them from afar, but I also laughed at them from above, as I considered some of their complaints so foolish, until I watched my son’s second grade baseball team.

His parents did this, my dad did it, and we all grew up complaining about it. “We were so close!” we’d complain. “I’d rather finish 0-fer than get that close again,” was our common complaint. Their complaints were so unrealistic they were funny. I laughed at them from afar, but I also laughed at them from above, as I considered some of their complaints so foolish, until I watched my son’s second grade baseball team.

When those seven-eight-year-old children played baseball, they made errors, and I had to stifle my snarky comments. “Of course he didn’t catch that ball,” I thought, “not when it was coming right at him, and it could’ve won the game for us.” I will provide this space right here ( ) for you to criticize me, slam on me, and analyze the deficits of my character. I deserve it, but I just could not click that hyper-critical, “I could do better. Even at their age, I wouldn’t have done that” portion of my brain off. I wouldn’t have done better, and I knew it, but I couldn’t tell me that, not in the moment.

We’ve all seen videos of parents overreacting saying such stupid things at their child’s game, and what we see probably isn’t even one one millionth of the times it’s happened. We’ve all seen those viral videos of parents screaming their heads off over the dumbest things, and we found them disgusting, sad, and hilarious. And I would’ve agreed with every single one of your characterizations of these people, until I became one of them. I didn’t unleash any of these thoughts, and to my mind no one knew how unreasonable and unfair I was, but those thoughts were in there, percolating their way to the top.

I could take a couple of errors here and there, as I wasn’t so demanding of perfection that I ignited over every single error, but there was always that one error, that over-the-top error, that just broke the dam for me. I’d leap to my feet and take my dog for a walk to get as far away as I could from everyone. I didn’t want anyone knowing what I was thinking.

All I can say, in my defense, is I’ve been watching sports and screaming things at TVs for as long as I can remember. I learned that we fans don’t have to sit quietly in the comfort of our own home when athletes are engaging in inferior play. I took those unfair and unrealistic expectations of college-aged images on TV to seven and eight-year-olds trying to play baseball. I never said anything aloud, and I knew my thoughts were unrealistic, unfair, and obnoxious, but I couldn’t stop thinking them after all those years of conditioning.

When our favorite college football team actually started to win so often that they won three national championships in four years, my friend’s family didn’t celebrate our victory, they were bored. Bored? Yes, bored by all that success. I knew this mentality so intimately that shortly after the Cubs won the World Series, I warned my friend, “This is really going to put a dent in your favorite team’s fan base.” Why? “Because the Cubs were lovable losers, and Cubs’ fans enjoyed complaining about them year after year. Every Cub’s fan could recite the rolodex of reasons why their beloved team hadn’t won a World Series for 100 years. The Cubs actually winning the World Series will turn out to be a poor business decision on their part. You watch.” I turned out to be wrong by a matter of degrees. Most Cubs’ fans are still loyal, more loyal than I thought they’d be, but they lack the fanatical fervor that the complaints about them not winning once fueled.

When our favorite college football team finally beat our inter-conference rival in resounding fashion, I celebrated each touchdown as if it was the first in a very tight ball game.

“Why are you still cheering this game on?” my friend’s dad asked. “It’s a blowout.”

“I don’t know,” I said, “But it might have something to do with all the pain they’ve caused us for decades. It feels like it’s finally over.”

“It’s still a blowout,” he said. “It’s a boring game.” It took me a long time to realize if this guy couldn’t complain about a game, he wasn’t all that interested in watching it. That victory was so complete that he didn’t have anything to complain about, and he basically had no reason to watch it anymore.

If I were to dig far too deep into this superficial element of life, I might say that complaining about sports so much that we’re screaming at the images on TV, and becoming so irrational about something we cannot control, is actually quite healthy in that it provides a non-confrontational outlet to unleash our anger and frustrations in life, as long as we don’t take it out of the home and into the public realm at our seven-to-eight-year-old’s baseball game.

***

“You can change his name if you want, and I won’t be offended,” a breeder said after I drove nine hours to pick up the puppy I just purchased from her. I was so sure she was being sarcastic that I said:

“Well thanks, that’s awful nice of you to allow me to name my dog?” in a tone I considered equally sarcastic. The breeder gave me a look to suggest our connections weren’t connecting.

“Well thanks, that’s awful nice of you to allow me to name my dog?” in a tone I considered equally sarcastic. The breeder gave me a look to suggest our connections weren’t connecting.

“Wait, do people actually keep the name you choose for the pets they purchase from you?” I asked her. She said she didn’t know, but she wanted us to feel free to change it.

I already had that eight-week-old puppy’s name picked out. I knew the name the breeder chose, as she listed it in the online listing, but I never even considered the idea that she might be offended by the idea that I would change it. She lived nine hours away, so we would never see her again. How and why would she be offended by this, and why and how would I care if she was?

When we purchase a puppy, we plan on keeping it for 12-14 years. Why would anyone want to keep the name someone else chose for it? That is so foreign to my way of thinking that I just thought everyone but the rare exception changed the name. I was shocked to learn how wrong I was. Since that interaction with the breeder, I began asking my fellow pet owners how they arrived at their dog’s name, “How did you pick that name, I like it?” I’d ask in the most polite frame I could.

A surprising number of people said, “It was their name when we purchased them.”

“You know you can change it right?” I asked. “Do you know how surprisingly simple it is?” Dog lovers know that dogs have unique personalities, but do they know that those personalities are not tied to their name? If we were to try to change a human’s name, say when they’re twelve-years-old, that would be a complicated procedure that would confuse the kid so much that we wouldn’t even think of doing it, except in rare cases.

Dogs don’t cling to names the way humans do. They adapt so quickly that a name change can be accomplished quickly. We did it in about two days with that puppy we purchased from that breeder, and it took about a week for the eight-year-old dog we purchased a year before.

“I know, I know…” my fellow pet owners said when I told them how easy it was to change a dog’s name. Some tried to explain why they felt the need to keep the name, but most just left it at “I know, I know…”

I don’t know if people lack creativity, if they don’t want the hassle of being creative, or if they fear they won’t be able to successfully change their pet’s name, but I met a family who purchased a rabbit and kept that rabbit’s name. “Does a rabbit even come to you when you call it?” I asked within my ‘Why didn’t you just change its name?’ frame.

“It does,” they said after debating among themselves. “But only when it wants to. He doesn’t come to you every single time you call him, as a dog would.” That debate involved family members who didn’t want to concede to the uncomfortable theme of my question that rabbits aren’t intelligent enough to know the difference.

“So, why didn’t you change the name?”

They never answered with thorough and complete conviction, but they did try to convince me that their rabbit was far more intelligent than I knew, which I interpreted to mean that they didn’t want to insult the beloved Binky the Bunny by arbitrarily changing his name to something they wanted it to be.

I conceded that I didn’t know how intelligent a rabbit was, but I said, “Who chose the name Binky? Do you think that sixteen-year-old pet store employee had greater insight into Binky’s being, his personality, and how he wanted to be identified?”

“He is Binky the Bunny,” they said. “That’s who he was when we purchased him, it’s why we purchased him, and it’s who he is now.” The other family members liked that answer so much, because it suggested that they, as a family, respected and liked Binky so much that by keeping the rabbit’s name it paid homage to his heritage and ancestry so much that they wouldn’t alter that by enforcing their will on him. There was also an implied notion that the move from the pet store to their home was so confusing and traumatic that they didn’t want to add to that by forcing Binky to adapt to their personal preference of a name. They didn’t say this, but they implied that they didn’t change the rabbit’s name, because they wanted him to know that his past mattered to them too.

Twenty years ago, I may have continued to argue against what I considered holes in their argument with the tenacity of a terrier on an ankle, but the smiles of joy surrounding me that day suggested that not only was my war against Binky unwinnable, but if I did somehow achieve some definition of victory my only prize would be a diminishment of those smiles.

***

“Why are you loyal to them?” a friend of mine asked. “They’re not loyal to you.” My friend said this when I told him that I just finished the year with no absences, no tardies, and the best quality scores I’ve ever accomplished as an employee. My uninformed guess is that this argument has probably been going on between employee and employer for as long as man has been employed by other men, but my Depression-era dad argued:

“No, that’s new to your generation, and probably a generation before yours, but we felt lucky to have a job.” Subjective critics of the modern era back my dad, “Companies and corporations actually cared about people back then [during The Depression and in the immediate aftermath]. Back then, employers kept people fed, happy, and alive. Businesses cared about people more back then. They paid more and gave better benefits back then. Now it’s all about the shareholders.”

‘So, you’re saying that The Depression-era companies and corporations didn’t have shareholders?’ I would ask those critics. ‘Or are you saying that they didn’t worry about them back then? Was that what led to The Depression? No, I know it didn’t, but did they worry about regaining the trust of the shareholders back in the aftermath of The Depression?’ My guess is the system was much more similar to the system we employ now than the subjective critics know.

‘So, you’re saying that The Depression-era companies and corporations didn’t have shareholders?’ I would ask those critics. ‘Or are you saying that they didn’t worry about them back then? Was that what led to The Depression? No, I know it didn’t, but did they worry about regaining the trust of the shareholders back in the aftermath of The Depression?’ My guess is the system was much more similar to the system we employ now than the subjective critics know.

“If you’re lucky enough to gain employment,” my dad taught us, “You stay with that employer for life.” That obviously didn’t penetrate, as my brother and I had numerous jobs before we landed great ones, but we met several fellow employees along the way who bought into my dad’s philosophy. Yet, we also found that their decades-long tenure at the company was not formed entirely by loyalty as much as it was fear. There were some who were loyal, some who were extremely loyal, but most of them stayed at the job that was no longer rewarding because they feared that they couldn’t do anything else, they were just happy to have a job, and they adjusted their life to how much money they made in that job.

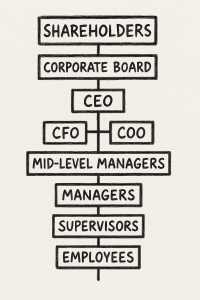

The subjective, cultural critics examine the system from the position that most corporations are evil and selfish. They embody this argument with the comparisons of CEO salaries compared to the average worker’s salary. To which I ask who is more valuable, valued, and replaceable? They would avoid this argument by complaining that most CEOs are evil, selfish, and some even argue that CEOs aren’t truly the top figureheads in the corporate hierarchy. That’s right, most of the figureheads sitting atop the corporate hierarchy are inhuman monoliths that we call the corporation, and these inhuman monoliths don’t care about humans anymore. I’ll let others argue for or against that, and I’ll focus on the more rational argument that those in corporate hierarchy don’t care about us. How do you define care? The members of your corporate hierarchy care enough to fulfill their end of the bargain we agreed to when we decided to be employed by them. They continue to pay us for services rendered, and they give us all the benefits they promised when we were hired. They also give employees performance-based raises, bonuses, and stock purchase programs.

If we don’t care for the various agreements we made with them anymore, we need to get competitive and see how competitive the other evil, selfish, and inhuman corporate monoliths are willing to get for our services. Before agreeing to that change, we need to focus in on what these other corporations have to offer us for our skills before we agree to work with them. Change, as we’ve all discovered, is not always better.

As for companies not caring, I’ve worked with supervisors who didn’t give a crap about me, and I’ve worked with others who cared a great deal. Our relationship with an employer is often defined by our relationship with our immediate supervisor. If we go further up into the hierarchy, we find that those people do not, in fact, care about us, but it’s mostly because they haven’t met us, and they don’t know us. They are required to create comprehensive corporate policies that try to make us happy while making their bosses happy.

When I applied for a mid-management job in our huge corporation, my supervisor said, “If you’re hired, you’re going to get the stuff rolling at you from both sides. You have to make the employees under you happy, and you have to make the employees above you happy. You need to accept the fact that if you become a boss, you will still have a boss, because everyone has a boss.”

The thing the subjective critics don’t understand is that their supervisor has to make their manager happy, and that manager has to make their bosses happy, all while trying to make you happy at the same time. And they all have to make a CEO happy, who has to make the corporate board happy, and the corporate board has to make the shareholders happy. Everyone has a boss. To make the shareholders happy, the corporate board convinces the CEO to work with the hierarchy structure under them to make sure all of the machinations of the corporation are so finely tuned that they create the most evil word in the subjective critic’s dictionary: profit.

If you reach a point where you loathe that word as much as the subjective critics who believe there is no reward for company loyalty anymore, you might want to seek employment with a non-profit. Before we leave the for-profit for the non-profit, we should know that their will still be a hierarchal structure that mirrors the for-profit, corporate hierarchal structure, but we will be able to remove that evil shareholders brick (stressed with disdain). After deleting them, we will need to replace it with a brick designated for those who provide charitable contributions, and/or the funders who offer grants. Even though the names are changed, those in the hierarchal structure will still feel scrutinized to the point that they feel the need to perform for their bosses, and at some point in our tenure with the nonprofit we’ll feel disillusioned, because we’ll come to the conclusion that they don’t care about us either, they just focus on performance.

***

There is one class of people who truly don’t care about us, criminals. Who are you? How do you define yourself? In ways significant and otherwise, we define ourselves by our stuff. We prefer to say the opposite at every outing, because we deem those who define themselves by stuff superficial and of diminished character. The moment after someone steals our stuff is the moment we realize that the stuff that defined us is now defining him, and we feel this strange sense of violation that informs us how valuable that stuff actually was to us.

When criminals steal something of ours, it offends us, because it feels like they’re taking elements of our character. Criminals don’t care about our attachments to stuff, and they don’t understand why we care so much about things. If they take one of our things, those things are theirs now.

When criminals steal something of ours, it offends us, because it feels like they’re taking elements of our character. Criminals don’t care about our attachments to stuff, and they don’t understand why we care so much about things. If they take one of our things, those things are theirs now.

When they spot something they want, they take it. It’s really not that different from the typical purchasing agreement we make with stores. We saw something on the shelves, and we took it. We paid the store for the product, yet money is an agreed upon, but artificial construct, if we view it from the criminal’s perspective. We took it from the store, and now they’re taking it from us. They don’t buy into that quaint and somewhat archaic idea of ownership the way we do.

Renee, my seven-year-old friend introduced me to this concept of the thief’s mentality when I spotted one of my Weeble Wobbles in her toy chest. “Hey, that was mine!” I said. “You stole it from me!”

She tried to convince me that her mother purchased it for her, until I pointed out a very specific flaw that her Weeble Wobble shared with mine.“Fine!” she said when she decided to give it back to me. She said that in a tone that suggested he didn’t understand what the big deal was. “I never saw you play with it, and I didn’t think you were using it anymore.”

“What? Even if I wasn’t, it was still mine, and if you wanted to borrow it, you should’ve just asked.”

“I said fine! Here,” she said, giving it back. We were seven-years-old, but in my limited-to-no experience in this field informs me that the misunderstanding of how the system works remains constant when I hear adult shoplifters try to compromise with store security by saying, “Here. Fine. I’ll give it back.” They hope by doing so, they can enter into an agreement with the storeowner that permits the storeowner to drop all charges. If that doesn’t work, they attempt to enter into an agreement with the storeowner, or manager, by saying they’ll pay for it. If the storeowner refuses, the criminal walks away thinking the store had a personal vendetta against them. It’s the thief’s mentality (trademarked).

At some point in this process, we’re taught to forgive and forget. “Everyone deserves a second chance.” If we refuse to forgive, our mothers, fathers, priests, and other authority figures teach us that holding onto anger, requiring retribution, and/or holding grudges have a way of darkening the soul. They say that learning how to forgive with all of our heart provides a spiritual cleansing that will pave the way for greater happiness. It’s true, and we know it’s all true. Yet, if we abide by the loving logic they teach us, and we decide to forgive the criminals for their violation, our relationship with the thief will arrive at another complicated definition of human interactions, when they steal from us again.