I considered the national obsession with hygiene a well-played, well-timed joke that we were all in on, until I witnessed two grown men form a friendship based on shared demands for hygienic excellence. In their conversation, they set up a standard of behavioral traits intended to define them as the next step in the evolutionary process that they believed might place them in a pseudo superman, or Übermensch, status beyond the inferior, basic hygiene practices of the common man and woman. I considered their hygienic standard so high that I thought they were exaggerating it for humorous effect. By the time their bond was sealed, however, I realized that this newfound friendship was based not only on respect for the other’s demands for excellence in this regard, but for their hygienic superiority.

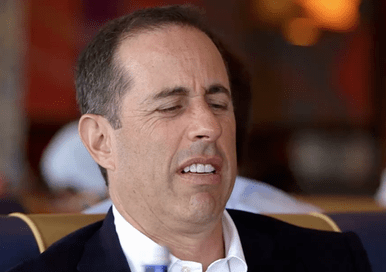

I loved the brilliant television show Seinfeld as much as anyone else. I found the main character’s obsessive demands for hygienic excellence so funny that when these two friends of mine began the list of requirements they had for their fellow man an impulsive laugh escaped me. After spending so many years laughing at Seinfeld’s obsessive quirks, my laughter was almost a conditioned reflex, but they weren’t laughing. They had smiles on their faces, but the smiles they shared were not of a sly variety that concealed a clever joke. Rather, they were kind, appreciative smiles, and a recognition that they finally found a likeminded soul in one another.

In the space normally reserved for laughter, they further detailed how the common hygienic habits of their fellow man were gross, and they both agreed that one particular person, our mutual acquaintance, was emblematic of those common habits. Without saying these exact words, they suggested he deserved all the shame that persons of modernity should cast upon him. I spoke with the two men separately a number of times, and they were well versed in the cultural norms, the belief that all men and women are created equal and we should accord them a degree of respect we require of them–unless, apparently, that person decides to leave the bathroom without washing their hands.

The implicit suggestion nestled within this discussion was that as the representative of one with common hygienic practices, I was supposed to recognize that I was gross and completely disgusting, and if I had any designs on becoming friends with either of them, I would have to seriously up my hygienic practices. I was to fear adding input into their conversation for that that might lead to an examination of my hygienic practices and a revelation that my habits were closer to our mutual friend’s than I ever knew. We might also find that what I considered an acceptable hygienic standard to be so disgusting and gross as to be worthy of some sort of public flogging in the public square to set an example for anyone else who might consider basic hygienic standards acceptable.

✽✽✽

“If you’re disgusting and you know it, clap your hands,” is the ostensible mantra of a major news network website that a number of my co-workers visit on a daily basis. The overarching milieu of this site is news, but the regular visitors of the site that I know are aware of little to nothing of the news of the day. Yet, they always have some nugget of information about how we can all improve our hygienic standard of living a little.

“Your kitchen counter is covered with more germs than your floor,” one of my co-workers said when he approached our lunchroom table. “Your dishrags and sponges are cesspools. Using them on a continual basis doesn’t rid your kitchen of germs. It only spreads them around.”

The idea that this particular purveyor of hygienic knowledge was male did not strike me as odd because I considered it less than macho to be hygienic, but he was the first man I met who would prove so obsessed with it. His warning would prove to be the first of many signposts to signal that the obsession I once believed indigenous to the female demographic had now crossed income brackets, social stratifications, and genders.

“Install a lighter-colored counter-top so you can see germs better.”

“Stainless steel is the best defense against the spread of germs.”

“The most germ-ridden room in most homes is the kitchen. Your cutting board can contain up to 200 times more fecal bacteria than your toilet seat.”

“Your fingertips can spread more germs than any tool in your kitchen.”

The best way to avoid germs, it appears, is to avoid the kitchen, the bathroom, and your fingertips. They’re gross! The bathroom is obvious, but what about your bedroom? Furthermore, if you have any thoughts of going into the basement, you might want to consider investing in a gas mask and a Tyvek suit with hood and boots. Your basement is a cesspool teeming with pathogens no one can pronounce! It’s gross! Disinfect everything! Sanitize! Sterilize! We need more government research on this matter! We could get sick! We could die!

The best way to avoid germs, it appears, is to avoid the kitchen, the bathroom, and your fingertips. They’re gross! The bathroom is obvious, but what about your bedroom? Furthermore, if you have any thoughts of going into the basement, you might want to consider investing in a gas mask and a Tyvek suit with hood and boots. Your basement is a cesspool teeming with pathogens no one can pronounce! It’s gross! Disinfect everything! Sanitize! Sterilize! We need more government research on this matter! We could get sick! We could die!

Our mothers taught us that the best way to avoid pathogens is to clean, but modern scientific research dictates that cleaning might be nothing more than a good start. Our mother didn’t know that the optimal way to avoid germs is to religiously and fastidiously clean the cleaning products to the point of sterilization. She used the same sponge and dishrag for more than a week without dipping it into a solution that contained one part bleach to nine parts warm water, and she used the same cleaning products for more than one task with no knowledge of cross contaminants. She didn’t know.

CBS News reports, “If you’re cleaning up appliances, counter- tops, tables, etc., it’s almost mandatory that you use different cleaning agents. There should be different designated sponges for each function. After you clean up the debris from the meat carcass, place your sponge in this cleaning solution for about a minute or so. That will kill all the potential pathogens.”[1]

Mom didn’t know.

Mom didn’t consider the idea of placing an industrial air shower to divide the kitchen from the rest of the house, because she was born in a generation that didn’t know anything about these hygienic standards of excellence. She might not have considered putting an industrial-strength anti-radiation shower in her kitchen for the sake of better health practices and greater avoidance of accidental pollination by pathogens. Mom didn’t have the information we do today, so how can we blame her? She didn’t know that it’s best to stay out of the kitchen altogether. Her generation wasn’t privy to the kind of scientific research that discovered that it’s probably safer to stay out of the house, unless that means going outside. The dangers inherent in leaving the house are so obvious that it’s not even worth exploring. We all know that the air outside is just teaming with pathogens, but our mom allegedly had no idea about this. She might have thought it was safe to send us outside to play, but she didn’t have the ubiquitous news sites clamoring for clicks, or the search engines that provide the latest tidbits of science in proper hygiene.

One of the worst conversations the creators of the Seinfeld show, Jerry Seinfeld and Larry David, brought to American life involved this obsessive level of hygiene. Conversations about hygiene occurred before the Seinfeld mindset began invading our culture and corporations began adding antibacterial agents to our soaps and body washes, but in the aftermath of that great show, it seems that every fifth conversation we hear now involves some form of obsession over cleanliness. We all thought Seinfeld’s obsessions were hilarious, but we had no idea how influential this mindset would prove to be. People now claim, with pride, that they don’t just wash their hands. They use a paper towel to open the bathroom door. “Oh, I know it,” the sympathetic listener proclaims with pride, “that handle is gross!”

No one has a problem with better practices that aim for cleanliness or those that strive for greater hygienic practices, but some, like my two friends, are so obsessed with it that they tip the scale of hygienic standards discussions toward superiority versus inferiority. When they spoke of our mutual acquaintance, the hygienic heretic, their disdain for him sealed whatever bond they needed to declare a friendship based on some kind of perverse superiority they felt regarding the man’s inferior habits.

✽✽✽

A Psychology Today (PT) by Rachel Herz piece details this perversity, stating that some obsessives even avoid shopping carts that have crumpled paper in them.[2] Why do they avoid those shopping carts, because they’re gross? A crumpled piece of paper is evidence that someone else used the shopping cart, at some point, since its creation. We know someone has used this cart before, of course, yet we regard visible evidence of it repellent. Supermarket and department store chains throughout the country have addressed this concern by putting antiseptic wet wipes near the shopping cart area, but that does not address the trauma of spotting a crumpled store ad in a cart. The only remedy for that is selecting another cart, but why should we be forced to select another cart? Why doesn’t someone address our concerns better? It would be one thing if the cart was home to a soiled piece of tissue paper, but what crime against humanity did the crumpled store ad commit? It’s evidence of other people, germs, pathogens, and a general lack of uncleanliness on the part of the store. It also initiates in us, “a desire to keep that which is outside from getting in.”

An interesting note about the emotion of disgust that Ms. Herz adds is that it’s both learned and selective. If a hygienic person with obsessive characteristics happens to see the person who left the crumpled ad in the cart and they find that person somewhat attractive, the potential cart user will not be as disgusted by the crumpled ad and the subsequent use of that cart. If they judge that previous cart borrower to be gorgeous, they will be even less disgusted. To take this idea to its logical conclusion, if the hygienic person with obsessive tendencies sees that the previous cart user was an attractive celebrity, that customer may feel privileged to use the cart regardless the celebrity’s hygienic practices. They might even save the crumpled ad and brag to their friends and family that the gorgeous celebrity touched it. If the previous cart user was somewhat overweight or of foreign descent, however, customers are more apt to select another cart, regardless that person’s hygienic standards.

Those who engage in obsessive hygienic practices also tend to be less inclined to be friends with those with physical disabilities, for images of frailty or illness lead us to avoid having anything to do with that person.

If those obsessed with hygienic practices had someone force them to share a toothbrush with someone, they would be more inclined to share it with a relative, rather than the mailman. This makes sense, because we are more familiar with our family members, and we assume we share some of their immunities.

What doesn’t make as much sense to those who believe their disgust has philosophical purity is the decision-making process that concerns those outside our immediate realm. We view our boss, for example, as a stranger who exists outside our immediate realm. We may interact with our boss daily, but this is not with the same level of intimacy we share with relatives. Our natural inclination is to place that boss below our family members, but the study also suggests we place our boss below the weatherman on the list of people with whom we would forcibly share a toothbrush. If our overriding concern were hygiene, why would we prefer to share a toothbrush with a weatherman we’ve never met to a boss we interact with on a regular basis? A weatherman is often better looking. The weatherman is often better-looking, clean cut, and better dressed. Moreover, there’s a greater possibility that we personally dislike our boss.

“Our attraction toward someone,” the Herz writes, “can override our qualms about sharing body fluids.”

There is one point of inconsistency in the PT article: “Those who avoid objects touched by strangers report fewer colds, stomach bugs, and other infectious ailments,” it states in one place, yet in another it offers, “Exposure to benign bacteria stimulates the immune system so that it is better able to fight bad bacteria.” Perhaps the explanation resides in the word “benign,” but other than that, the two purported facts appear to be contradictory.

The Origin of Disgust

Contrary to internet myths and our own preconceived notions on the subject, disgust is not an innate emotion based on self-preservation. Disgust is, rather, a learned behavior that we learn more about every day, exacerbated by every news report and website we read. Despite the fact that a baby might twist up his face in disgust when force-fed strained squash, his expression does not have a direct link to disgust. Studies suggest that the baby doesn’t really know disgust until they’re 3 years old. “If we were to make a look of disgust to a baby, say when we take out the garbage,” Rachel Herz writes, “the infant is more apt to think we’re mad at them for something than to associate the look with disgust, until they’re three years old.”

This is why babies have no problem eating whatever they find on the floor. It is also why they have no problem crawling through what we consider disgusting debris. They have no understanding of what they should find disgusting and what is not, no matter how often we tell them. It’s the reason my brother and his wife had to keep my nephew away from the dog dish, because he didn’t recognize the difference between the liquid his parents served him in a bottle, and the liquid we place in the dog’s dish.

This is why babies have no problem eating whatever they find on the floor. It is also why they have no problem crawling through what we consider disgusting debris. They have no understanding of what they should find disgusting and what is not, no matter how often we tell them. It’s the reason my brother and his wife had to keep my nephew away from the dog dish, because he didn’t recognize the difference between the liquid his parents served him in a bottle, and the liquid we place in the dog’s dish.

“Even after we achieve three years of age,” Herz writes, “we don’t have a total understanding of disgust. It is the most advanced human emotion that requires reasoning, thought, and deduction. Humans are the lone animal with a brain advanced enough to process the complexity of disgust, and that knowledge occurs with experience and over time. It is also something we learn more and more about every day, and we get more and more grossed out by what could be deduced as minimal when it comes to actual infection.”

Those of us who used to think exaggerated obsession with hygiene was nothing more than a brilliant characterization and one of the best recurring jokes to support that joke, now know how wrong we were. We’ve learned that these characteristics can aid in the pursuit of psychological dominance, and they can form friendships with fellow travelers on the road to hygienic excellence.

“You’re all just silly,” I told the two men that formed a friendship based on their hygienic standard. “You’re obsessed with all this.”

“Hey, better safe than sorry,” one of them said. I received that response before from the obsessed, so I expected it. I didn’t expect him to expound on that typical response, “If more people were as obsessed as I am, as you say, I wouldn’t have to be the way I am.”

“I guess,” I’ve responded, “but you do recognize that all these reports about pathogens and sterilizing sponges and counter-tops hit home with some people, until they’re afraid to enter their homes or anyone else’s or go outside. I don’t know anyone who takes all these reports seriously, to the point of adjusting their habits accordingly, but I’m sure there are some. If you met such a person, wouldn’t you consider them silly?”

“Well, yes and no.”

I was disgusting and I didn’t know it, until I met these two. I knew I wasn’t disgusting, but group thought can be difficult to thwart when the one in the minority hasn’t studied the subject in question. The idea that these two men were extreme was not lost on me, of course, but I needed an extreme from the other pole to counterbalance their subtle condemnations. For that, I turned to comedian George Carlin:

“I never take any precautions against germs. I don’t shy away from people who sneeze and cough. I don’t wipe off the telephone, I don’t cover the toilet seat, and if I drop food on the floor, I pick it up and eat it! My immune system gets lots of practice! It is equipped with the biological equivalent of fully automatic military assault rifles, with night vision and laser scopes … and we have recently acquired phosphorous grenades, cluster bombs, and anti-personnel fragmentation mines …. So, when my white blood cells are on patrol, reconnoitering my blood stream, seeking out strangers and other undesirables, if they see any—any—suspicious-looking germs of any kind, they don’t [mess] around. They whip out the weapons, and deposit the unlucky fellow directly into my colon! Directly into my colon! There’s no nonsense. There’s no Miranda warning, there’s none of that three-strikes-and-you’re-out [mess]. First offense, BAM! Into the colon you go.

“Speaking of my colon, I want you to know I don’t automatically wash my hands every time I go to the bathroom, okay? Can you deal with that? Sometimes I do. Sometimes I don’t. You know when I wash my hands? When I [mess] on them! That’s the only time, and you know how often that happens? Tops, tops, two to three times a week … tops! Maybe a little more frequently over the holidays. You know what I mean?

“And I’ll tell you something else my well-scrubbed friends… you don’t need to always need to shower every day, did you know that? It’s overkill, unless you work out or work outdoors, or for some reason come in intimate contact with huge amounts of filth and garbage every day, you don’t always need to shower. All you really need to do is to wash the four key areas; armpits, [anus], crotch, and teeth. Got that? Armpits, [anus], crotch, and teeth. In fact, you can save yourself a whole lot of time if you simply use the same brush on all four areas! [3]

[1]http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-500178_162-697672.html?pageNum=2&tag=contentMain;contentBody

[2]Herz, Rachel. “The Cooties They Carry.” Psychology Today. August 2012. Pages 48-49.

[3]https://www.lingq.com/lesson/george-carlin-fear-of-germs-235986/