“It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important.” — Antoine de Saint-Exupéry in The Little Prince

“I know one guy we’ll be able to find in the dark,” some anonymous kid whispered loudly in the halls of our school.

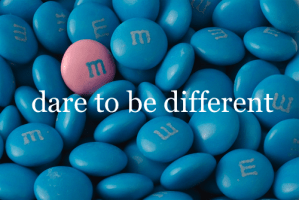

And it wasn’t just him. I was getting it from all corners, and they were pounding me and hounding me for wearing a pair of bright, baby blue shoes to school. I thought of saying things. I could’ve said, “They’re shoes for God’s sakes. They’re just shoes,” but I’m sure victims of public executions screamed similar things to those calling for blood. I thought of telling them that my dad picked these shoes out and a number of other lies, but I was overwhelmed, and they were in a mood. The truth was I took my time and carefully considered these shoes. I thought they might finally help me establish myself as a freak of nature who dared to be different, and they did.

“Are you sure?” my dad asked me before we took the shoes to the checkout stand, “because I wouldn’t wear them in public.” I wasn’t sure. I wasn’t sure of anything, but I thought the shoes were flashy, and I was anything but flashy. I also thought they were Michael Jackson, and I loved Michael Jackson, but when you go Michael Jackson, you better prepare for some attention. The thing was I thought I was prepared. I did things to garner some attention, but the moment I walked into the town square, that we call the classroom, with those shoes on, I realized this was another league.

My dad implored me to try on a pair of more conventional pair of white canvas shoes with blue stripes, and I did, and I knew the “theys” in my school would accept them, but I was drowning in the but-Is. But I love those baby blues, but I don’t want conventional shoes, and I knew I should go the comfortable, conventional route, but I was just accused of being a conformist by some of my really good friends.

“You only like the Rolling Stones, because Paul does, and you only like the Seattle Supersonics, because Mike does.” They were kid charges, but I was a kid at the time, and they were true. I wouldn’t admit anything of the sort to them, of course, but I had to admit it to myself. Prior to this humiliation, I still considered Michael Jackson the greatest entertainer in the world. Michael Jackson was still about twenty million albums sold away from reaching a level of market saturation that required us to say, “Michael Jackson sucks!” to pledge allegiance to the cool, so I still loved Michael Jackson. I didn’t know anything about rock or the Rolling Stones, but Paul did, and Paul was the coolest kid in school, so I decided to become a Rolling Stones fan. I also thought David Thompson and Johnny Drew were the greatest basketball players in the NBA. I didn’t even know the NBA had a franchise in Seattle, but after Mike told me they were his favorite team, I looked into them, and I saw that they were green, and I liked green teams. I also liked the alliteration in the team’s name, because I loved the letter ‘S’. When I learned that their best player had the exotic name “Downtown” Freddie Brown, and another one named Gus, I began following them and cheering them on, because I loved those names. Then they went and won the NBA championship that year, and I became a huge fan, but I wouldn’t have been a fan, in the first place, if I didn’t want to be like Mike.

“You only like the Rolling Stones, because Paul does, and you only like the Seattle Supersonics, because Mike does.” They were kid charges, but I was a kid at the time, and they were true. I wouldn’t admit anything of the sort to them, of course, but I had to admit it to myself. Prior to this humiliation, I still considered Michael Jackson the greatest entertainer in the world. Michael Jackson was still about twenty million albums sold away from reaching a level of market saturation that required us to say, “Michael Jackson sucks!” to pledge allegiance to the cool, so I still loved Michael Jackson. I didn’t know anything about rock or the Rolling Stones, but Paul did, and Paul was the coolest kid in school, so I decided to become a Rolling Stones fan. I also thought David Thompson and Johnny Drew were the greatest basketball players in the NBA. I didn’t even know the NBA had a franchise in Seattle, but after Mike told me they were his favorite team, I looked into them, and I saw that they were green, and I liked green teams. I also liked the alliteration in the team’s name, because I loved the letter ‘S’. When I learned that their best player had the exotic name “Downtown” Freddie Brown, and another one named Gus, I began following them and cheering them on, because I loved those names. Then they went and won the NBA championship that year, and I became a huge fan, but I wouldn’t have been a fan, in the first place, if I didn’t want to be like Mike.

To compound my humiliation, one of my other good friends informed me that the whole Stones/Sonics thing was a big set up. “The idea that you are so susceptible to suggestion has been the source of silent whispers for weeks,” he said. “The fellas loved it, and Paul and Mike loved it so much that they decided join in.”

“Paul?” I said. “There’s just no way. You’re making that up.”

“Paul?” I said. “There’s just no way. You’re making that up.”

“You didn’t know it, but he told you that he thought the Rolling Stones sucked, two weeks ago, just to see if you’d go around telling everyone that you thought they sucked, and you did,” my good friend reported. “Then, last week, he told you he was a huge fan of The Stones, and you went around telling everyone you loved The Stones.”

I did it, I realized with a sizable gulp. I fell for all it. The sense of betrayal went deep, because prior to that incident I considered Paul a best friend. Had I developed a brain complex enough to examine my actions with some objectivity, I might’ve said, “Listen, I don’t have older brothers, like the rest of you, and I don’t have any kids on the block to school me in even the most basic, kid version of the critical thinking involved in knowing the Michael Jackson sucks and the Rolling Stones rules. My whole identity is wrapped up in this amalgamation of your ideas about what it means to be cool, and I thought you, my best friends, wouldn’t mind showing me the way. I was wrong, and you were right, but who’s the bad guy in this production, he who follows, or he who leads … astray?”

I was on my own, in other words, and I figured that these shoes might inform them that I finally had an identity free from others’ influences. I thought that once my friends recovered from the shockingly bright colors of the shoes, they would come around to see them for what they were. I thought they were just a beautiful pair of shoes that captured my personal definition of beauty, and I naively believed a pair of shoes might accelerate my gestation into a bright, baby blue butterfly. Of all the driving forces I’ve listed here to becoming a freak who dared to be different, I honestly don’t remember which was my primary motivation, but I remember learning, for the first time, the swift, harsh, and resolute penalties for independent thought.

As much as we hate to admit it, some calls for conformity can actually be a good thing, as we all teach each other what is socially acceptable. We don’t do this for altruistic reasons, of course, as we enjoy judging others who don’t know, because it makes us feel like we do. We do it to be mean, and to make others laugh, but we inadvertently spare our subjects the pain they might experience later on down the road. As I stated earlier, I had no one to teach me societal and cultural norms, so “they” stepped in and taught me in all their mean and funny ways. There were other things they taught me, but I learned that as much as I wanted to be a freak who dared to be different, I didn’t play have the constitution necessary to pull it off, so I diverted.

“How did that survive high school?” I now asked adults who never diverted and weren’t afraid to let their freak flags fly.

“It’s who I am,” they’ve said in varying ways. I could’ve said that too, as I believed in the power of baby blue, but that would’ve opened a whole can of why I didn’t pursue it that I did not want to talk about. They also said, “It’s who I am,” with such power and conviction that I couldn’t help but think about how I went back to the store to return those bright, baby blue shoes. The “It’s who I am,” crowd were a little freaky in all the ways I was, and there was probably something wrong with them in the manner there was something wrong with me, but they didn’t duck and run for cover, they stood tall. Rather than be ashamed of their eccentricities, they embraced them. The potshots they took from all corners only emboldened them, and their current freakish appearance stated they obviously maintained that posture into adulthood. They fascinated me, because there’s a part of me that wishes I would’ve held onto my own relatively small level personal freakdom freedom, even if it was nothing more than a relatively odd, different, and a little freaky color of shoes. I just didn’t have what it took to defeat the comments, jabs, and ostracizing, but I do wish I would’ve put up a better fight.

“It’s who I am,” they’ve said in varying ways. I could’ve said that too, as I believed in the power of baby blue, but that would’ve opened a whole can of why I didn’t pursue it that I did not want to talk about. They also said, “It’s who I am,” with such power and conviction that I couldn’t help but think about how I went back to the store to return those bright, baby blue shoes. The “It’s who I am,” crowd were a little freaky in all the ways I was, and there was probably something wrong with them in the manner there was something wrong with me, but they didn’t duck and run for cover, they stood tall. Rather than be ashamed of their eccentricities, they embraced them. The potshots they took from all corners only emboldened them, and their current freakish appearance stated they obviously maintained that posture into adulthood. They fascinated me, because there’s a part of me that wishes I would’ve held onto my own relatively small level personal freakdom freedom, even if it was nothing more than a relatively odd, different, and a little freaky color of shoes. I just didn’t have what it took to defeat the comments, jabs, and ostracizing, but I do wish I would’ve put up a better fight.

“It is the time you have wasted for your rose that makes your rose so important,” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote in The Little Prince. The “It’s who I am” crowd won the battles that defined their identity crisis, and I lost, but one of the reasons they probably fared better in those battles is because it was far more important to them. The battle for my baby blues seemed important to me at the time, but I gave up so easily that it obviously wasn’t. Whatever the particulars were, the “It’s who I am” crowd probably wasted so much time and energy on their fight that they became what they were fighting for. I think about these angles, all of them, when I see a face full of piercings, a body completely covered in tattoos, or freaky hairstyles and colors, and I wonder if that’s the extent of their creative expression. I gained a limited perspective on what they must have gone through, and I envy the fortitude they obviously displayed in their battles, but I wonder if they fought so hard back then that that’s who they are now.

I lost, I got pounded into smithereens, and I walked away with my tail between my legs, but I eventually took a full three-hundred and sixty degree turn back into myself to discover other freakish avenues better suited to me through my ideas of creative expression. Who wins? It’s all relative to the person, of course, but I believe the other avenues I chose proved more conducive to the kind of freak I am today. When I chose this avenue, writing articles like this one, I found that I was able to say, “It’s who I am!” with an exclamation point as opposed to a comma. My definition of different is more subtle than those superficial ornamentations, it’s more cerebral, and more conducive to becoming a person who focused his creativity on matters other than the “It’s who I am” crowd who explore superficial expressions on their body. It’s always subject to internal debate, of course, but I’ve finally reached a point where I can appreciate all of the hundreds of battles, big and small and internal and external, I’ve been through in life, and how they whittled me into what I’ve become.