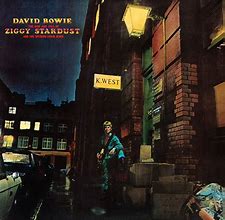

“Don’t bend. Stay strange.” –David Bowie

“All children are born artists, the problem is to remain artists as we grow up.” –Pablo Picasso.

“We don’t grow into creativity, we grow out of it.” –Ken Robinson said to further the Picasso quote.

“Don’t bend. Stay Strange,” is such a simplistic and beautiful quote that if we heard it earlier in life, some of us might have stitched it out on oven mitts, T-shirts, and flags.

“What’s it mean though?” we ask,

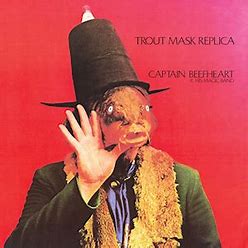

David Bowie answered in an appearance on a 70’s show called The Midnight Special. It’s difficult to capture the effect that weird, strange, and just plain different appearance had on me all those decades ago. I was floored. I was flabbergasted. I craved the weird, even when I was young. Even before I knew the totality of what embracing meant. When Bowie walked out, I thought it was shtick. I waited for him to break out some Steve Martin-ish routine, and then he started singing. Bowie’s commanding voice informed me this was not an affectation. It was a full-on embrace of the weird. It made me uncomfortable, but it also confused me. I was so young, and so confused, that I considered his appearance unsettling, and I needed help dealing with it.

David Bowie answered in an appearance on a 70’s show called The Midnight Special. It’s difficult to capture the effect that weird, strange, and just plain different appearance had on me all those decades ago. I was floored. I was flabbergasted. I craved the weird, even when I was young. Even before I knew the totality of what embracing meant. When Bowie walked out, I thought it was shtick. I waited for him to break out some Steve Martin-ish routine, and then he started singing. Bowie’s commanding voice informed me this was not an affectation. It was a full-on embrace of the weird. It made me uncomfortable, but it also confused me. I was so young, and so confused, that I considered his appearance unsettling, and I needed help dealing with it.

“He’s just weird,” she said. She was trying to comfort me. Her message was he’s so weird that he’s probably being weird for the sake of being weird, and that we should dismiss him on that basis. I argued that I didn’t think so. “If that’s the case,” she said, “we probably don’t want to peel that onion.” I didn’t want anyone to consider me weird, so I tried to dismiss him. I couldn’t look away though. I never saw anyone embraced the weird before. I thought weird was what we whispered when we saw it walking down the street, and we walked a lower case (‘b’) around it.

If Bowie dropped this quote on me, as a kid, it might have helped me through the swamp, but I don’t think Bowie would’ve dropped such a line on a kid. Rock stars are generally impetuous creatures, but I would hope that David Bowie wouldn’t be so reckless as to advise a child to embrace the weird. I think he reserved such notions for relatively stable, confident adults. If he followed that impulse, I think he knew it might cost that kid some happiness, for the world is so confusing to a kid that they need to embrace normalcy until their minds are strong enough to embrace the weird. I also think such a quote might mess with that young person’s artistic cocoon. I think Bowie knew, from firsthand experience, that the struggle to maintain the weird defines the artist in constructive, creative ways. To paraphrase the Picasso quote above, the problem isn’t how to become weird, strange, and just plain different. The problem is to maintain it as we work our way through the mire and maze of childhood.

The chore of the artist is to maintain the element of weird, while melding it with the normalcy of adulthood. Those of us who were weird had some weird ideas that were weird for the sake of being weird. We were passionately weird, and learning how to form an identity. We’re now glad there are no records of our strange thoughts. We needed seasoning. We needed to understand norms better if we were ever going to constructively mock, ridicule, or upend their conventions. This perspective is particularly vital to writers, as it gives them an outside perspective from which to report on those who followed their passion throughout life and embrace the weird, strange, and just plain different.

***

Some scholars, like Sir Ken Robinson, want us to violate this theory by changing school curriculum to accommodate the weird, strange, and just plain different. In his popular Ted Talk speech, Robinson cites anecdotal evidence to suggest that we should change the curriculum to recognize the unique and special qualities of weird, strange, and just plain different students.

Some scholars, like Sir Ken Robinson, want us to violate this theory by changing school curriculum to accommodate the weird, strange, and just plain different. In his popular Ted Talk speech, Robinson cites anecdotal evidence to suggest that we should change the curriculum to recognize the unique and special qualities of weird, strange, and just plain different students.

Shouldn’t they learn the rules first? Most writers were wildly imaginative kids, and when our kids flash their unique fantastical worldview before us, we remember how weird we used to be. We fondly remember how imaginative and creative we used to be. Our kids reignite that internal, eternal flame in us. We remember how special it was to be imaginative without borders, but we also remember how unstable and confusing that time was. We were impulsively and instinctively imaginative without borders, and we smashed through whatever borders they put in our way, but most of the results of our beautiful and wonderful childish creativity was gobbedly gook.

We didn’t know what we were talking about because we were kids. We didn’t do anything worthwhile, even when we were wildly creative, because we didn’t know what we were doing. We were kids. When we think of the rules, we often think of some humorless school master enforcing discipline at the end of a ruler, but we often forget how many little, seemingly inconsequential matters we learned along the way to help form our thoughts into mature creativity, and how a stew of those little, relatively inconsequential matters and our wild creativity made us who we are today.

There will always be prodigies, but what percentage of the population do we consider prodigies? For the rest of us, there is a special formula to achieving final form. This painfully methodical process involves rebelling against our establishment, succumbing to it, recognizing its inherent flaws, and returning to our rebellion with an informed mind. As I wrote in the Platypus People blog, “one of our first jobs of a future rebel is to learn the rules of order better than those who choose to follow them.” The idea that the manner in which school curriculum deprives, stilts and discourages creativity is a strong one, but do these scholars remember how confusing the adolescent years could be for the kids who weren’t prodigies? Lost in this discussion is our need to understand that which we now deem unreasonable, irrational, and in need of change. Why does this work, how does that work, and how and why should we change this to that?

“I welcome your complaints, but if you’re going to complain, you better have a solution,” our teachers told us. The crux of that line is the difference between weird for the sake of being weird and constructive oddities. How can we form a solution to the artistic complaints we have, if we don’t first understand the problem better than those who are just fine with it?

The perfect formula, as I see it for the creative artist, as Pablo Picasso said, is to remain weird after learning the curriculum and surviving the need to conform. When we learn how to read, write, and arithmetic, we use them to fertilize the science of creativity. If an artist can maintain their fantastical thoughts after learning, they might be able to employ the disciplines they need to enhance their creative and innovative mind to artistic maturity.

We don’t know many specifics of Sir Ken’s dream school, but one of the fundamental elements he theoretically employs is the need to play. The creative mind, he says, needs time and space to play. Throw them a block and let them play with it, and we’ll see their ingenious minds at work. He dots his speech with humorous anecdotes that serve to further his thesis. We know that Wayne Gretzky spent much of his youth playing with a stick and a hockey puck in every way he could dream up, and we learn that other kids develop their own relatively ingenious little theories by playing. We cannot forget to let them play. It is a well-thought out, provocative theory, but it neglects to mention how important discipline is in this equation. The discipline necessary to figure out complicated mathematical equations and formulas might seem frivolous to a dance prodigy, for example, but Geometry works the mind in many ways it otherwise wouldn’t.

“Why do I have to learn this?” we all asked in Geometry class. “What are the chances that I’ll ever use this knowledge? If I become the vice-president of a bank, what are the chances that knowledge of the Alexandrian Greek mathematician Euclid’s theories will come into play?” One answer to the question arrives when we meet a fellow banker who knows nothing but banking. For whatever reason our fellow banker knew she wanted to be a bank vice-president at a very young age. Her focus was such that she had the tunnel vision necessary to succeed in the banking world, but everyone who knows her knows the minute she clocks out for the day, she’s lost. She might be successful by most measures, but she knows nothing about the world outside of banking, because she never needed any knowledge beyond that which exists in banking.

“How can you report on the world, if you know nothing about it?” is a question I would ask everyone from David Bowie to the twelve-year-old prodigy who wrote a fantasy novel. The kid’s story fascinated me, because writing a 200 page novel is so foreign to my concept of what it means to be twelve-years-old. I was trying to make friends and be happy at twelve-years-old. I read the news article about this kid with great interest, and if I ever ran into him, I would encourage him to see his talent to its extent, and I would applaud him for what he did, but I would never read his novel. I don’t think a twelve-year-old’s vision of the world would do anything for me.

Sir Ken Robinson doesn’t say that he wants to do away with the core curriculum directly, but in his idyllic world, we need to cater it to the talents of people like this twelve-year-old prodigy, the dance prodigies, and all the other as of yet unrecognized prodigies around the world.

We’ve all heard tales of these uniquely talented creative people and prodigies with tunnel vision. We marvel at their tales, but we’ve also heard tales of how former prodigies don’t know how to fit in the world properly. They’ve reached their goal by producing a relatively prodigious output, but they’re now unhappy.

How could they be unhappy when people pay them to do something we’d pay someone to do? If the word unhappy doesn’t do it for you, how about unfulfilled? Their weird thoughts of the world are not an artistic affectation.

Something fundamental is missing in them that they’ll never square properly. Being on the proverbial stage is the only thing that gives them joy, and they understand this as little as we do. It might have something to do with being in the spotlight their whole lives, but it might go deeper than that. It might have something to do with the fact that their authority figures never forced them to be normal, and they never had to learn the basic, core answers the rest of us learned by working through all of the pointless exercises that our core curriculum required. “So, if I take a Geometry class, I’m going to be less confused about the world?” No, but if you learn how to learn how to use your brain to figure out the tiny, relatively meaningless facets of life, it might help you arrive at answers that help you cope with the otherwise random world a little better.

Robinson might be onto something when he suggests that if we feed into a prodigy’s creative instincts, we might have more of them, and they might be happier people as a result. His thesis suggests that most people are unhappy because they have untapped talent that we neglect to foster. Let them play, he says. Fine, I say, but why can’t we let them play at a dance school, in art class, or in a school band? Why can’t we just throw a block at them in their free time? Do we have to devote our entire curriculum to helping them recognize their talent? A strong, confident adult is so difficult to raise that as much as I would’ve loved some devotion to recognizing my weird talent, I think I would’ve ended up deficient in so many other areas that I would’ve been miserable. Devotion to recognizing my weird talents would’ve made me happier in the short term, as I think I was always heading down a certain road I didn’t recognize for some time, but I think I’d probably would’ve ended up more confused than I already am.

“Don’t bend. Stay strange,” is the great advice David Bowie passed on, but I think it should only be used by those who manage to maintain some of the creativity they had in youth and managed to remain artists. Most artists think they could’ve been prodigies if someone came along, recognized their talents, and coached them up, and many think they wasted so much time in school learning things that didn’t matter? Robinson feeds into these fantasies with some anecdotal evidence that suggests if we would’ve just danced more, we might have discovered that we were dance prodigies. He suggests that if we, as parents, learn how to feed our child’s talent, they might be happier. If the child’s interests are satisfied, they might be more satisfied. Possibly, but if we devote our entire curriculum to dance, creative writing, painting, or one of the other art forms, how many failed upstarts might we have? Students mature at different rates, and while developing schools devoted to encourage more creativity, it will likely result in unequal amounts of misery among those we consider prodigies based on their wild imaginations, but they were actually engaged in nothing more than child-like gibberish.