“We can rebuild you. We have the technology. We can help you live longer.”

“But I don’t want to live longer!” we say when we find out they’re talking about aggressive, life-prolonging treatment. “I want to die with dignity!”

“But I don’t want to live longer!” we say when we find out they’re talking about aggressive, life-prolonging treatment. “I want to die with dignity!”

Most of the conversations we have on this weighty topic do not involve doctor, patient confidentiality, in doctors’ offices or emergency rooms. Most of them occur in bars and employee cafeterias, where we say, “I hope I never have to face such a situation, but if I do, I don’t want machines keeping me alive. I’ll choose dying with dignity.” The conversation participants are often thirty-to-forty somethings who hopefully won’t face such scenarios for forty-to-fifty years.

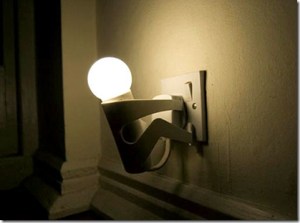

“What we’re talking about is being hooked up to machines and/or computers, and that’s scary.” Of course it is. If it’s not scary, then the patient is either the bravest person we can imagine or someone who doesn’t understand the question. Some take it to terrifying heights in hypotheticals, which leads me to believe they’ve probably seen too many worst-case scenarios, in the movies. They think if we fall prey to our desire to mess with nature, or God’s plan, by living a few more months or year, they’re going to wake in a hospital to see a half machine, half human cyborg staring back at them in a mirror.

“I don’t care, I don’t want any tubes sticking in me, and I don’t want wires sticking out of me,” they say, “I ain’t going out like that. I want to die with dignity.”

Talk is cheap of course, and I think most of us will choose life, depending on the bullet points of the detailed explanation we face, but there are the “I don’t care. I ain’t going out like that” types who become combative when someone approaches them with a mask, an intravenous needle, or an intubation tube.

Talk is cheap of course, and I think most of us will choose life, depending on the bullet points of the detailed explanation we face, but there are the “I don’t care. I ain’t going out like that” types who become combative when someone approaches them with a mask, an intravenous needle, or an intubation tube.

We’ve all heard real-life scenarios involving gruesome illnesses, and we sympathize with the decisions that have to be made, but I just don’t understand the hypothetical and categorical denials of advanced care. I think it boils down to tradition, as we’ve all heard the horror stories our loved ones envision when it comes to technological advancements, and their repetition influences our answers. It makes no sense to them that machines and computers can prolong life. “Anytime you put something in, something else falls out,” and “For every action there is a reaction,” they say to make note of the unnatural, irrational, and in some ways immoral technological extension of life. They believe that messing around with nature, or God’s design, will produce unforeseen consequences.

“When it’s my time, it’s my time, and I’ll be ok with that,” they say, and we all smile and gain greater respect for them saying that.

“Ok,” I want to say, “but what if there is a chance that you could live a quality life following a procedure. Will that definition of a quality life be somewhat reduced, likely, but what if it could still be a quality life?”

Most of the people I know, through these conversations, categorically reject any form of hypothetical talk of some diminishment, and they drop that “Dying with dignity!” line. It might just be the people I know, or it might be human nature, but most of us default to cynicism when we make leaps to worst-case scenarios when it comes to the technological advances that other faceless entities developed. It’s that term faceless entities that we

\

latch onto, as we develop fears that these technological advancements have occurred with little to no human involvement. (I think we can thank/blame the repetitive messaging from sci-fi movies for that.)

I heard a story about a person who was so adamant that they let her die that “she became fighting mad” when the talk of prolonging her life occurred. In her defense, the prognosis was that “they” figured they might only be able to prolong her life six months to a year, with treatment. Those last two words stoked her ire. “What does with treatment mean?” she asked, but she stopped them in the midst of their explanation. She didn’t want to know. Talk is cheap, as they say, but she didn’t want to hear such talk. “I don’t fear death, or being forgotten. I want go out gracefully.”

Hearing what she went through, and her fighting stance, this is my proclamation: “If I’m lying there on my death bed, with nothing but machines keeping me alive, don’t pull the plug, resuscitate as many times as you have to, and keep me alive no matter what. I don’t care if I’m a vegetable who can only communicate through a series of beeps, like that Stephen Hawking guy. I love life, and I don’t want it to end. Once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

That’s funny, right? Is it funny because no one says that, even at lunch in employee cafeterias and afterwork, barroom hypotheticals. Everyone I talked to says pull the plug, turn it off, and do not resuscitate. They don’t even need a moment to think about it. It’s almost an instinctive response now. No one says I want to live as long as I can, no matter what. Most people choose death with dignity, because the opposite is the opposite that they don’t even want to discuss. Yet, if you talk to these people often enough, you’ll learn that dying with dignity seems more important to them than living with dignity. Some of the things they do, and we have to keep in mind that if they’re telling us about these things, what are they too ashamed to reveal. When you hear these things, you realize that they don’t mind doing things that make us think less of them in life, but when it comes to death, they choose dignity.

We’ve been spooked. Someone somewhere convinced us that medical procedures, technological advancements, and even a brief stay in hospitals (“I hate hospitals!”) is worse than the alternative. What’s the alternative? “I’ll tell you what the alternative is. It’s preferred!

“If I found out I have diabetes,” Bruce continued, after his award-winning preferred joke. “I’d rather die than go through all their treatments. Have you heard what the treatments are for diabetes? No thank you. I’m not going to monitor my blood sugar levels, take insulin and other oral drugs. They talk about having a healthy diet to combat your symptoms, and that sounds all great and all when you’re sitting in a doctor’s office, until you learn what a healthy diet means. If you want me to maintain a proscribed weight, I have a warning for you. I won’t. I’ll tell you that I will, and I’ll mean it in the moment when I’m sitting in a hospital gown with my ass exposed, but once I put my denim back on, I’m going to eat whatever the hell I want. You might think it doesn’t take much to ascribe to a healthy diet, until they start in on that list. At some point, a healthy diet comes into conflict with what the quality of life. They also talk about engaging in regular physical activity. Regular physical activity sounds as doable as a healthy diet when you’re all scared in a doctor’s office, and we’ll agree to exercise more … for about a week. Then we’ll fall back into our usual routine when we’re feeling all healthy again.” After a couple months, or however long it takes for our refusal to follow their edicts to catch up to us, they’ll eventually put me on kidney dialysis. Do you know what that is? It’s basically a machine that they hook you up to to take all your blood out of your body, clean it, filter it, and all that crap, until it’s time to put it back in us. Can you really picture me doing that, seriously? The final straw will take place when they tell us to at least monitor my sugar intake. The message, therein, will be to try to avoid sugar and carbohydrates as much we can. I’ll be frank with you, I’d rather die. I’d rather die than have anyone see me say no to a Snicker’s bar.”

Anytime I think I exaggerate the glamorization of death some fixate on, I hear stories that mirror Bruce’s “I’d rather die than go through all that.” I also hear stories about people purchasing caskets, tombstones, and plots when they’re in their thirties! “I want a casket in a quiet, shaded area, because I was forced to live by a railroad that was always so noisy.” We dream about our funeral, picturing our people crying and all that, and we want them to say something like, “She denied treatment, because she didn’t want to go out like that. That’s the way she wanted it, and we respected her wishes in the end.” We might get that conversation, but it might also get interrupted when the home team scores a touchdown on the television in the reception area. That’s fine, but it’s so important to us that our friends and family remember that we ‘died with dignity’ that we creatively expand that line. We don’t want the ‘how she died’ to earmark us throughout history. We don’t want others to say, “Did you see her at the end? It was so sad. She was so vibrant and fun for most of her life, but in the end, she was a vegetable.” We don’t want to see that look of disgust, because we know that look, we’ve given that look to others. We all hope that we’re never in these situations, where doctors force our loved ones to make decisions, and if we are, we want them to know we’d rather die.

Most of us will never face such a situation, with our lives or the lives of immediate family members for whom we must make such decisions, but those who see it on a regular basis, choose death. A recent study found that 88.3 percent of doctors who regularly pursue aggressive, life-prolonging treatment for patients facing the same prognosis, said that they would choose “no code” or do-not-resuscitate (DNRs) orders for themselves. They see what their patients go through, and they prefer death.

Let’s not gloss over this. Those who know far more than we do about these situations choose a dignified death. We can talk about situational hypotheticals all we want, and the intrinsic value of life over death, but those who see the suffering of patients on a daily basis, who know what family and loved ones go through watching their loved one die, would prefer to forego pursuing aggressive, life-prolonging treatment. Is that shocking? I think it is, but I’ve only had one experience with a loved one in such a situation, and the decision we made was basically a forgone conclusion by the time we made it. Needless to say, my answer is an uninformed one, but those I spoke with in cafeterias and bars were just as uninformed as I was, and they chose death.

The most common response for “no code” and DNR decisions is the quality of life, followed by medical prognosis, personal beliefs, autonomy and avoiding becoming a burden. The latter, we can only guess, is largely financial, but there is also the physical burden of counting on your loved ones to provide physical assistance. Most people don’t care for all that, they prefer death.

Contrary to much speculation, we won’t get to come back and see how our decisions affected our loved ones. Once we’re gone, we’re gone. Life is over and there ain’t no coming back. Who cares what they say or think, I say, live long and prosper. If there is an afterlife, and we end up looking up, down, or around at the aftermath of our decision, my bet is that we’ll wish that we wrung every droplet of water out of the sponge before we went into the great unknown? I don’t know what I’m talking about here anymore than you do, but if that fateful day ever arrives, and I’m forced to make that decision, I think I’ll choose life.