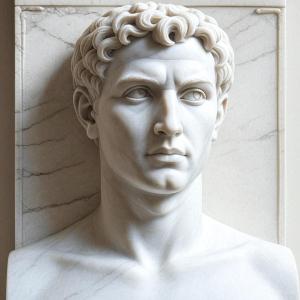

The most powerful man in the world wasn’t just mad, he was raging. His furious anger stemmed from the fact that Roman law prohibited him from killing whomever he pleased. The law stated that he could only murder non-citizens, prisoners of war, and slaves, and he had Romans saying he wasn’t just wrong, but corrupt. He didn’t think the most powerful man in the world, at the time (AD 37-41), should have to put up with that. To right this wrong, the emperor of Rome, Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus Germanicus, better known as Caligula, created a law that would allow him to kill whomever he damn well pleased.

After issuing this law, Caligula didn’t just want to kill dissenters, detractors, and other enemies, he wanted to send a message. He commissioned the purchase and shipment of five of the largest lions that his minions could find to be shipped from North Africa to Rome. They found five five-hundred-pound lions. Reports suggest he ordered lions, based on what his advisors called “Their unique dietary habits. Tigers and panthers kill before consuming flesh,” they informed him. “Lions prefer devouring their prey while it is still alive.” We’ve all watched these scenes play out on TV, a tiger stalks their prey, and after catching them, they go for the throat to suffocate their victims before gorging on them. They do this, for the most part, to prevent getting injured during the skirmish. Caligula’s advisors informed him that Lions don’t have such concerns. They informed him lions “prefer devouring their prey while it is still alive.” While this is not necessarily true, the promise of excruciating agony thrilled Caligula, and he wanted that scene, and that amplified message, sent to all future opponents.

After issuing this law, Caligula didn’t just want to kill dissenters, detractors, and other enemies, he wanted to send a message. He commissioned the purchase and shipment of five of the largest lions that his minions could find to be shipped from North Africa to Rome. They found five five-hundred-pound lions. Reports suggest he ordered lions, based on what his advisors called “Their unique dietary habits. Tigers and panthers kill before consuming flesh,” they informed him. “Lions prefer devouring their prey while it is still alive.” We’ve all watched these scenes play out on TV, a tiger stalks their prey, and after catching them, they go for the throat to suffocate their victims before gorging on them. They do this, for the most part, to prevent getting injured during the skirmish. Caligula’s advisors informed him that Lions don’t have such concerns. They informed him lions “prefer devouring their prey while it is still alive.” While this is not necessarily true, the promise of excruciating agony thrilled Caligula, and he wanted that scene, and that amplified message, sent to all future opponents.

We can speculate that Caligula’s opponents informed some elements of the historical record, as often happens in the years following the end of a world leader’s rule. Some of it might be 100% true, some of it might be based on the truth but exaggerated, and some of it might be hearsay and outright fiction. If this characterization is even close to the truth, however, we can guess that Caligula also chose lions, because he thought they would provide great theatrical value. The record states, in numerous places, that Caligula had a particular fondness for blood and all of the screaming that comes from long and intense torture.

Caligula chose five lions for the five most pesky, annoying and frustrating dissidents who challenged his authority on a routine basis. He alleged that they were engaged in a plot to depose him. Caligula also knew that anytime we deal with nature, they’re unpredictable. He was probably advised that there is the possibility that these lions might do nothing when they see humans, and that his show could fall flat. To assure maximum entertainment for himself, and his audience, Caligula ordered the lions’ handlers to avoid feeding them for the three days preceding the event.

Caligula chose five lions for the five most pesky, annoying and frustrating dissidents who challenged his authority on a routine basis. He alleged that they were engaged in a plot to depose him. Caligula also knew that anytime we deal with nature, they’re unpredictable. He was probably advised that there is the possibility that these lions might do nothing when they see humans, and that his show could fall flat. To assure maximum entertainment for himself, and his audience, Caligula ordered the lions’ handlers to avoid feeding them for the three days preceding the event.

For all the theatrical torture Caligula planned, there were no public mentions of bloody carnage he planned. There were no mentions of it on the billboards Caligula commissioned scriptores (professional sign painters) to create, or in the pitches heralds were commissioned to shout in forums or streets. There was also no mention of whether this was a pay-per-view event, as Caligula carried on the tradition of making entry free for all audience members.

The billboard and heralds did not advertise violence for violence’s sake, as historians like Suetonius portray Caligula as craving chaos in the arena, such as beating a gladiator manager to death slowly or burning a playwright alive mid-performance. They characterize Caligula as someone who preferred spontaneity when it came to the violent scenes involved his shows. Did it make him feel more powerful to order a playwright to be torched in the middle of his reading, or did he just get bored? The historians characterize most of the violence occurring during Caligula’s events as those resulting from impulsive orders to liven matters up a little, as opposed to any form of proactive promotion to attract crowds.

When the event Caligula planned since the day he put the law in place finally took place, the five dissidents who dared speak out against Caligula were given short swords in defense, but as with most brutal sports, the purpose of giving them short swords was to prolong the event. They proved more ineffective than Caligula imagined, as the five starved, five-hundred-pound lions devoured the dissidents in twenty-five minutes, not as long as the average situation comedy of the modern era.

Caligula found the sight of the ferocious power of the lions, blood, and all the screaming, thrilling, but after all of the planning and work he put into the event, he was disappointed that it was all over so fast. As a man who enjoyed theatricality, we can only guess that he was divided over being personally bored and worried that his audience may have found his event boring.

During the intermission, Caligula summoned the arena guards to his private suite, and he ordered them to invite individuals in the packed, 15,000 capacity amphitheater to participate in a second act with the lions. (The record does not clarify if Caligula selected the individual audience members to invite, or if he allowed the guards to select them randomly. It does state that at times, he ordered entire sections to participate in events.)

How random was random might be the first question the invited asked. Did random mean that the arena guards selected some who were loyal to the emperor, others who weren’t, and everyone in between? If random is truly random, did the guards choose women and children? We don’t know. No matter who those first randomly chosen participants of the second act were, we guess that they had some questions for the guards, as they were being led through the chambers to the floor of the amphitheater. We can guess that they probably thought that they were all a part of Caligula’s wild and crazy sense of humor. They probably guessed that he would stop the proceedings at the last second and have a laugh at their expense. They may have flirted with the notion that this was a test of their loyalty to the emperor, and they probably tried to outmatch each other in displays of loyalty. Whatever the case was, they realized they were wrong when the lions began encircling them.

When they began screaming and pleading for mercy, Caligula found that as entertaining, if not more than the first act. He probably tried to remain stately, but as the lions began ripping them apart, he couldn’t control his laughter anymore, as they cried and screamed. Did the audience laugh cheer at the spontaneous spectacle of this second act, according to the record they did. The question is why? Did they have a bloodlust that enjoys any and all bloodsport, or did they fear if they didn’t cheer, they could be next?

If this is all true and not exaggerated, we could say that TV has saved countless lives since its invention, because an overwhelming majority of us just love violence. We have a need for violence coursing through our veins. It’s a part of our primal nature. We might watch it and cheer it on from our couch with some reservations, but we still cheer it on.

We have a couch, they had a sedes (Latin for seat) in an amphitheater. They watched Caligula’s show from a distance, we watch a TV programmer’s show from a distance. What’s the difference? Well, there’s fiction versus non, but what happens when a fictional shows’ creators fail to produce a realistic murder scene? We’ve all seen graphics that were a bit hokey, and an actor who failed to properly simulate the pain involved in their death scene. It’s a cheat, right? We say things like, “There’s ninety minutes of my life I’ll never get back!” We don’t mind it when creators use computer-generated-imagery (CGI) if it adds to our experience. If a creator can make it more real for us and provide us the satisfactory, vicarious experience of murdering someone, we’re all in. If the actor “Flopped like a fish out of water!” after being riddled with bullets, we might laugh in the same manner Caligula laughed at the screams and cries of the victims of the creative ways he found to cure boredom. And we may have both said, “Now that’s entertainment!” at the end of the show. If we say that and laugh in the company of someone else, they might say, “That’s just wrong on so many levels!” We might agree, but we both know that no one was actually harmed during this production, and we had our bloodlust for bloodsport satisfied. How many of us have left an excessively violent TV show or movie so satisfied that we no longer felt the need to commission the purchase of five, five-hundred-pound lions to rip our enemies apart? How many lives has TV saved?

When we hear people say we live in the best of times and the worst, the ‘yeahbuts’ talk about how they’d love to visit historical figures from the past. We get that, but what would we say to those historical figures? Would we inform a Caligula that history will not be kind to him? Would you tell him that that has a lot to do with his impulsive rage and the carnage that follows? Fortune telling and prophecy were so deeply woven into Roman life during Caligula’s reign that he might have viewed our claims as a visitor from the future as nothing more than a new branch of the whole fortune teller circuit. As evidenced by the historical record, Caligula did not deal with negative news in a rational manner, and our fact-based information about his legacy “from the future” could’ve landed us in the center of his show screaming and pleading our case with five, five-hundred-pound lions looking at us as an ideal way to curb their hunger.