If I enter a public restroom and see you, you’re guilty of whatever happened in there until proven innocent, and the more you plead your innocence, the more guilty you look.

The Gomer

Most of us have been insulted so often and in so many creative ways that it’s almost impossible and pointless to catalog. Nestled within those insults are a few jewels that are so colorful and intriguing that we cannot wait to use them. I’m not exactly sure why I latched onto this particular slang insult from the 90s, but when Ty said, “You’re such a Gomer!” it sounded so much like an insult I would use that if an insult can ‘fit like a glove’ I could almost feel the leather sucking on my contours.

“Gomer?” I asked. “What is a Gomer?”

“If you have to ask,” Ty said. “You’re a Gomer.” That reply wasn’t new to me of course, but it informed me that I was stepping into a kafkatrap in which I was The Trial’s Joseph K., accused of an infraction against cultural awareness, and any effort I put into clarifying the situation only deepened my apparent guilt and reinforced the accusation. It also created the perfect insult loop, because any questions I asked only further authenticated the insult and somehow brought the condition into being.

Most subjects of this insult loop would recognize the kafkatrap for what it was and drop the line of questioning there, which would allow the accuser to bask in their glory. Yet, I found it so delicious that I thought I might want to test drive it on my own one day, so I wanted to fully understand its power base. “Does it date back to the 60s television show Gomer Pyle?”

“I don’t watch TV.” It was cool back then, as it is now, to feign ignorance.

“Well, what does it mean then?”

“I don’t know,” Ty said with impatience. “But it fits.”

After obsessing over this, I discovered that the term began after the prophet Hosea’s wife, Gomer, acted unfaithfully, and it thus served to symbolize God’s relationship with unfaithful Israel, but I was pretty sure that didn’t form the basis of Ty’s insult. I was also sure Ty wasn’t referring to the emergency room jargon from a book called House of God by Samuel Shem that referred to them shouting, “Get Out of My Emergency Room,” to annoying patients who repetitively took beds that should’ve been reserved for more deserving patients. No, I decided, the term was derived from the TV show Gomer Pyle, a character played by Jim Nabors, as a clumsy, unsophisticated fella who was folksy and awkward.

Even though the truth was somewhat anti-climactic, as I expected a more sophisticated and nuanced answer, I still enjoyed the sound of the insult “Gomer”. I don’t know if it was the syllabic nature of the word or the enunciation, but “You’re such a Gomer!” just felt like such an airtight insult that I couldn’t wait to use it on the unsuspecting. It just seemed so me. To my memory, I never got around to it. I know it’s not too late, but I forgot to use it back when it had the flamboyant style and battlefield visibility of prominent feather plumes (AKA panache), and it’s one of the great regrets of my life.

Dads

We all enjoy hearing about the father of an extremely successful person remaining stubbornly unimpressed by their son’s success. The rest of the world cannot believe how talented this man is, but his dad, the man he probably strove to impress more than anyone else in the world is, “Meh.” It’s your child, the little fella you could hold in one hand while you changed his diaper with the other, all growed up ruling Hollywood, and you’re, “Meh.” It’s funny and sad at the same time.

After reaching the pinnacle of success in Hollywood, Jerry Lewis decided he wanted to share the wealth with his father. Lewis came up with what he considered the perfect way of doing it. He approached members of the General Motors corporation and asked them to build his dad the finest automobile they could possibly build. When the father, Danny Levitch, was presented with this gift, he said, “What you couldn’t get me a convertible?” That’s so cynical it’s funny, right? It’s Seinfeld funny. We can’t decide if it’s so funny it’s sad, or if it’s so sad it’s funny, but it strikes us as sounding so true that it is funny … and a little sad.

After reaching the pinnacle of success in Hollywood, Jerry Lewis decided he wanted to share the wealth with his father. Lewis came up with what he considered the perfect way of doing it. He approached members of the General Motors corporation and asked them to build his dad the finest automobile they could possibly build. When the father, Danny Levitch, was presented with this gift, he said, “What you couldn’t get me a convertible?” That’s so cynical it’s funny, right? It’s Seinfeld funny. We can’t decide if it’s so funny it’s sad, or if it’s so sad it’s funny, but it strikes us as sounding so true that it is funny … and a little sad.

This story provides a small window into Jerry Lewis’s relationship with his dad. Due to the comedic nature of it, we might consider it a highlight, but what happened in the days in between? What happened to Jerry Lewis when he was too young to understand it all, then old enough to know that he was being raised in a loveless home? The car story provides a laugh, but what happened on those boring Thursdays and during the Holidays in that home Jerry Lewis grew up in? According to Lewis, he was never close to either of his parents.

Danny Levitch was a failed vaudeville actor who may have been jealous of all of Jerry’s success, and he may have considered the car an example of Jerry Lewis rubbing his nose in his success. Hard to know what happened in the inner sanctum of the family dynamics, but Jerry and his parents never reconciled, and Jerry was later known to be a distant father to his own kids, as all six of them had a strained relationship with him throughout his life. He even went so far as to cut them all out of his will before he died.

I don’t know if Mr. Levitch was a “tough love” proponent, who was constantly pushing Jerry harder, because he thought praise weakens, or if he did what he did to try to keep his wildly successful son grounded, but at some point he probably should’ve closed the loop. These loops are facades we create to force our children through for their betterment. Some parents create beautiful! and wonderful! facades of too much praise, because they believe it strengthens their child’s self-confidence, their morale and resolve, and some parents do the opposite to keep their kids grounded and to prepare them for the perseverance required for the rough world that awaits.

My dad was an opposite. Whenever we accomplished what we accomplished, he spotted the possible fly in the ointment that no one considers while in the glow of accomplishment. He often talked about how luck always plays something of a role, and the lucky should always prepare for the times when they aren’t so lucky. “It’s great advice dad, but how about we take a moment to bask?”

Whenever we saw an individual driving a high-priced vehicle, my dad would say, “We don’t know how much he owes.” When everyone else was buttering our bottom, our dad was warning us about the other foot landing a solid blow to the keister. It was what he considered “the real” side, which just happened to be the critical, cynical side. He did this throughout our maturation and into adulthood. The difference between my dad and Mr. Levitch, and all those negative Nancies who focus far too much on the dark side of life, is that he eventually closed the loop.

“I’m so proud of you and your brother,” he said one day, almost out of the blue. If someone threw out a hypothetical scenario, beforehand, in which my dad offered me unqualified praise without conditions, I would’ve said, “First of all, it will never happen, but if it did, it probably wouldn’t mean a lot to me.” Much to my surprise, it turned out to be one of the more meaningful moments of my life. I still remember the intersection we were approaching when he said it, and it’s been fifteen years since that happened.

Did Mr. Levitch build a facade for his son by withholding praise, love and forgiveness for the expressed purpose of making his son a hard man who is invulnerable to insults and criticism? And did he maintain that facade, even on his deathbed? We don’t know, but we know Jerry Lewis did by cutting his children out of his will. While I’ve never been on a deathbed, I have to imagine that would be a pretty good time to let bygones be bygones and let our guard down to express love, pride, and forgiveness. It’s also an excellent time to close all the loops we’ve created for their own good, and … it’s actually hilarious when we don’t. Except to those who want to hear their loved one say one kind thing to them before they go to the great beyond. I didn’t have to go through this, because my dad eventually closed that loop, but if he didn’t, I can only imagine that all of the holes in my soul would’ve coalesced into one big, hilarious black hole.

Mary

“You don’t like Mary?” I ask. “I can understand not liking Trisha and Natalie, they’re 50% people; 50% of us like them and 50% don’t, but Mary? How can you dislike Mary?” Mary has her flaws of course, and we all become qualified professionals when it comes to spotting other people’s flaws, but with Mary, we really need to dig deep to find them. The next question we will ask ourselves, soon after we find ourselves in the depths of Mary’s caves and caverns, is why am I here again? That’s right, we started this whole expedition because there was something about Mary that exposed something we didn’t like about ourselves.

Funny is a Funny Thing

I knew a life-of-the-party type who could just dominate a room when he was “on stage” at various get-togethers and various shindigs, but he couldn’t even make you smile one-on-one. I knew “a quiet guy” who could drop you with a perfect comeback, a great one-liner, and an incredible story. Call him out at a party, and he clams up. He said things in those group settings, but they were all self-conscious. “I get nervous,” he’d say. He basically experienced stage fright in front of seven or eight people, even when they were just family members. I met a guy who was a hilarious writer, but in person he could never quite pound a joke home. He was one of those joke tellers who was always editing, and by the time he got to the punchline, we were basically exhausted, and we laughed sympathetically. As an amateur student of psychology as it pertains to humor, I’ve never met anyone who was funny in person, on stage, and on the page.

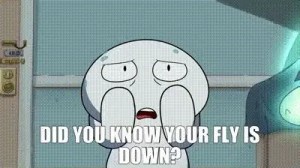

Your Fly is Down

As a failed student of comedy, I cannot abide by the “Your fly is down!” joke. One character in the series Stick made a funny, insightful comment about how wolves must be embarrassed to see what we’ve done to manipulate their species into yorkies, pomeranians, and shih tzus. The other character says, “Your fly is down.” This is now so common that it’s a trope in most comedic productions, and I don’t understand how it became something we consider a pointed, substantive, or even clever comeback?

If someone asked me my least favorite joke, I probably couldn’t come up with it on the spot, but if someone else said, “What about the ‘Your fly is down’ joke?”

If someone asked me my least favorite joke, I probably couldn’t come up with it on the spot, but if someone else said, “What about the ‘Your fly is down’ joke?”

“That’s it!” I’d say. It’s one of those jokes that only works in-person. In a situation comedy, written in, presumably, a writer’s room, how does this get a thumbs up from a head writer? How does the head writer not say, “We can do better than that, c’mon guys. That’s a Friends joke. Surely, we can do better than recycling a Friends joke.” If I were writing this exchange, I would have the butt of this fly joke say, “Okay thanks,” as he zips his zipper up, “but that doesn’t take away from my observation.” The ‘Fly down’ rebuttal is somehow viewed as one character putting another in their place, and it must be viewed as effective in some quarters, because so many writers write it in as dialogue. Personally, I’d like to have a word with the world to have them help me finally put this insipid “Your fly is down” joke out of its misery.

Tictacs de un Reloj

The ticks of the clock in Mr. Harrington’s Spanish II class were so painfully slow that I still remember looking up at that clock with clenched teeth. When the second hand descended from one to six, that clocked performed its functions as we’d expect. When it ascended from six to twelve, the most important part, it struggled. It bounced a little, as if the mechanisms behind its ascent were lacking power. Even though I had nothing better to do at the time, I thought nothing was better than anything we did in that classroom.

As we age and look back at our schooling years, most of us regret not paying more attention in school. I’m as guilty of that as anyone else, but after crossing that bridge o’ regret, I now recognize that I would be just as bored in Mr. Harrington’s class today as I was as at sixteen-years-old. I now have corporate boardroom meetings to remind me how slow a clock can tock.

As we age and look back at our schooling years, most of us regret not paying more attention in school. I’m as guilty of that as anyone else, but after crossing that bridge o’ regret, I now recognize that I would be just as bored in Mr. Harrington’s class today as I was as at sixteen-years-old. I now have corporate boardroom meetings to remind me how slow a clock can tock.

Prison guards often say that after spending years in their profession, they often begin to feel held captive as much as the prisoners. Mr. Harrington was our warder, as he appeared to loathe being in the class as much as we did. He often joked about how many hours he was away from his retirement package, and he obnoxiously calculated that over the course of two years of in-class hours.

Now that I’m old and happy, time ticks away so quickly that the only thing that makes me a little unhappy is watching how efficient our clocks are now. Yet, if I were on my death bed watching those clicks of the clock bounce by far too quickly, and an entity appeared offering me six more months of life, I would accept it of course, until he offered me the requisite “catch” of such offerings. “The catch is you have to go back in time and attend Mr. Harrington’s class for one hour of each day you’re being offered.” I would still eventually accept his offer, because life is life, and I have to imagine I would recognize its value in that moment, but I might ask the entity to explain the glory of the unknown to me to weigh it against my personal definition of earthly hell.

Permission! Permission

“It’s pointless to give advice to young ‘un’s,” old people often say about the young. “They don’t listen.” True, but we didn’t listen either. We heard them, but everything they said went in one ear and out the other. Before it went out the other, however, it did hit a way station. We were teenagers, we had our first job, and we were cashing our own paychecks, so of course we weren’t listening.

I’m not going to say, “I never got nothing,” (triple negative) but everything I got, before those paychecks, came with a whole lot of begging, pleading and badgering. I’m not still complaining about that but illustrating that everything “I got” came with the most evil word in the teenage lexicon: Permission.

I’m not going to say, “I never got nothing,” (triple negative) but everything I got, before those paychecks, came with a whole lot of begging, pleading and badgering. I’m not still complaining about that but illustrating that everything “I got” came with the most evil word in the teenage lexicon: Permission.

Those first, sweat-drenched paychecks taught me about something I only heard about when I was a teen, purchasing power. Purchasing something without permission was the greatest high I received to that point in my life, a high no drug or alcohol could duplicate. To me, it was better than a girl’s smile. And the “Theys” in my life tried to coach me into being more responsible with my money. It didn’t happen right away, as the dizzying feelings of euphoria lasted long after I went broke displaying that power. It took a number of paychecks and repetitive feelings of embarrassment, humiliation, and feelings of utter powerlessness before I tried to find that way station again and the advice therein to try to put it back in the other ear. If that young ‘un you’re trying to advise is anything like I was, give them that advice and realize that “they won’t listen,” until they make their own mistakes so often that they try to remember what we said.

The Relative Quality of Relative Quality

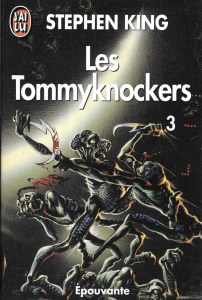

“That’s such an awful book (album or movie),” they say about the works with which I develop a relationship. “I can’t believe you liked it.” Tommyknockers is often deemed one of the worst books Stephen King ever wrote. The ending was so anticlimactic that I think it left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth, but there were moments, in the buildup, when Tommyknockers captivated mein a way few books ever have. Rock critics and KISS fans say that their Music from The Elder album was not only KISS’s worst album, but it might be one of the worst rock albums ever made. I’ll never know the truth, because my connection to that album is so strong I’ll never be able to analyze it objectively. I could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure the greatest divide between my friends and members of family and I arrived with a production called The Blair Witch Project. I’ve never watched the movie again, after seeing it at midnight on the night (morning?) of its release, but that movie reached me on a level no other movie has. “Isn’t that the whole point,” we ask critics and fans. To paraphrase Picasso, “The writers’ job is to create something and then give it away.” When they create it, it’s a nutshell of their passion, and they hope to give that passion away to us. Those of us who love these artistic creations cannot answer questions of quality in a dispassionate manner, because the authors of these creations reached us in a way that led us to fall in love with them in a manner similar to teenage, puppy love that is so irrational that it cannot be factually supported or refuted.

“That’s such an awful book (album or movie),” they say about the works with which I develop a relationship. “I can’t believe you liked it.” Tommyknockers is often deemed one of the worst books Stephen King ever wrote. The ending was so anticlimactic that I think it left a bad taste in everyone’s mouth, but there were moments, in the buildup, when Tommyknockers captivated mein a way few books ever have. Rock critics and KISS fans say that their Music from The Elder album was not only KISS’s worst album, but it might be one of the worst rock albums ever made. I’ll never know the truth, because my connection to that album is so strong I’ll never be able to analyze it objectively. I could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure the greatest divide between my friends and members of family and I arrived with a production called The Blair Witch Project. I’ve never watched the movie again, after seeing it at midnight on the night (morning?) of its release, but that movie reached me on a level no other movie has. “Isn’t that the whole point,” we ask critics and fans. To paraphrase Picasso, “The writers’ job is to create something and then give it away.” When they create it, it’s a nutshell of their passion, and they hope to give that passion away to us. Those of us who love these artistic creations cannot answer questions of quality in a dispassionate manner, because the authors of these creations reached us in a way that led us to fall in love with them in a manner similar to teenage, puppy love that is so irrational that it cannot be factually supported or refuted.

Fix-It Man!

Some of us are perpetually caught between our inability to fix our things and not wanting to spend the money to have another fix them. It’s always kind of embarrassing to admit we were not born with the ability, or more importantly the patience, to fix things. I make a mistake, and it becomes clear to me that I’m a total screw up who can’t do things. Other people make the same mistakes, and they simply start over from scratch and fix it correctly. My inferiority complex leads me to panic when I don’t do things perfectly.

The Conditional Secret

Just out of curiosity, I read Secrets to a Happy Marriage articles. I’m not going to write that they’re totally useless, but they contain advice that falls under the term The Forer Effect. The Forer Effect is most often witnessed in horoscopes, in which their writers apply descriptions, advice, et al. that could apply to everyone. Personally, I think the best advice I’ve ever heard is that relationships between adults are not unconditional. My guess is that most marriages end because the participants mistakenly believe that their marriage should be unconditional, and one or more of the spouses fail to express what their conditions are. Unconditional love should be reserved for the parent/child relationship. As fortune seekers often say, in their quest for treasure, more adventure and glory is found in the chase than in actually securing the pot of gold. If we want to make an individual, who happens to be our spouse, happy, we should know that there are super-secret elements to a happy marriage to be found every day. If you’re a great spouse who wants to have a happy marriage, you’ll seek those super-secrets and capitalize on them when they make their appearance, but there will probably be more glory found in the chase.

Just out of curiosity, I read Secrets to a Happy Marriage articles. I’m not going to write that they’re totally useless, but they contain advice that falls under the term The Forer Effect. The Forer Effect is most often witnessed in horoscopes, in which their writers apply descriptions, advice, et al. that could apply to everyone. Personally, I think the best advice I’ve ever heard is that relationships between adults are not unconditional. My guess is that most marriages end because the participants mistakenly believe that their marriage should be unconditional, and one or more of the spouses fail to express what their conditions are. Unconditional love should be reserved for the parent/child relationship. As fortune seekers often say, in their quest for treasure, more adventure and glory is found in the chase than in actually securing the pot of gold. If we want to make an individual, who happens to be our spouse, happy, we should know that there are super-secret elements to a happy marriage to be found every day. If you’re a great spouse who wants to have a happy marriage, you’ll seek those super-secrets and capitalize on them when they make their appearance, but there will probably be more glory found in the chase.

Hiding in Hyde

In the movie Entourage, based on a TV series of the same name, the main character secures the rights to a movie called Hyde. The main character (of Entourage) informs his agent that for him to participate in Hyde, he wants to direct it. The agent begrudgingly concedes, and to make a long, boring story short, Hyde turns out to be: “Brilliant!” of course. If you watched the TV series, you know the main character is a leading man who has leading man, movie star good looks, and he gets everything he wants in life. No one, agents, directors, friends, family, or women, dare say no to the man. He’s the top of the list, king of the hill, and an a number one of the charmed life demographic.

In the movie Entourage, based on a TV series of the same name, the main character secures the rights to a movie called Hyde. The main character (of Entourage) informs his agent that for him to participate in Hyde, he wants to direct it. The agent begrudgingly concedes, and to make a long, boring story short, Hyde turns out to be: “Brilliant!” of course. If you watched the TV series, you know the main character is a leading man who has leading man, movie star good looks, and he gets everything he wants in life. No one, agents, directors, friends, family, or women, dare say no to the man. He’s the top of the list, king of the hill, and an a number one of the charmed life demographic.

Those of us on the outside-looking-in know such people exist. We’ve met them, viewed them from afar, and we’ve even developed relationships with some of them. Some of them are athletically gifted, intellectually superior, and/or charismatic types who light up every room they enter, but in my experience, they’re almost never creative types.

The typical creative type is not born with the gifts of the charmed. Their creatively is honed through effort, failure, and the struggle to succeed. Failure is often the key, because the typical creative type starts out awful, laughably awful, and some of their beta readers are not afraid to laugh. The typical creative type perseveres, not because they want to prove their detractors wrong, but because it’s who they are, or who they’ve become.

Those of us on the outside looking in must grapple with the idea that we’re jealous of “IT!” guys, because we are. Who wouldn’t want to live one day of their lives? If we can step beyond that argument and have a rational discussion, I don’t see how anyone can lead such a charmed life and be creative. We all know there are exceptions to every rule, but it just seems implausible that this charmed individual can create something “Brilliant!” in his directorial debut. (It should be noted that the Vincent Chase character did not write the screenplay for Hyde, but there are so many ways in which a director creatively shapes a script that requires creativity.)

If Entourage: The Movie wanted to have a deep, psychological hook, it should’ve carried a central message that this main character could have it all, in all of the believable ways he did, but he could not achieve creative brilliance too. He’s never had to struggle to develop such skills, and he’s never failed to the degree that he scorched the earth of his initial plans, started over, and learned from all that humiliation and embarrassment to create something “Brilliant!” It should’ve carried the message that something “Brilliant!” is often created in the ashes of all that.

The main character, as depicted throughout the eight seasons of the Entourage series, never had much of a struggle. The fictional film in the movie, Hyde, should’ve bombed critically and commercially, as a superficial film of no substance. It didn’t, of course, as the star proved his detractors wrong, which in effect made the film Entourage: The Movie, a superficial film of no substance.