“The Patriots won, because they cheated,” Patriots’ haters say when asked to explain the unprecedented level of success the Patriots enjoyed between 2001 and 2018. I am not a Pats fan, but I am not a hater. I did not enjoy the long-term level of success they achieved, but I did appreciate it from afar. As much as I’d love to join the chorus of the haters, the cheating charge doesn’t explain the nine Super Bowl appearances made in the Belichick, Brady, and Kraft era. Even if they were 100% guilty of the offenses the NFL found (“And those were the times they got caught!” haters add) it doesn’t taint their six (SIX!) super bowl trophies. Even the most outspoken Pats hater has a tough time explaining how underinflated balls helped the Patriots appear in eight straight AFC Championship games between 2011 and 2018. “Tom Brady could grip the ball better,” they say. So, underinflated balls explains how the Patriots managed to achieve the only undefeated 16-game regular season since 1972, and the fact that they came one miraculous play away from beating the hottest team in football that year? During the Kraft, Brady, and Belichick era, the Patriots completed 19 consecutive winning seasons from 2001 to 2019, and they boast a .784 winning percentage against their division opponents. In Brady’s 18 seasons as a starter, the Patriots played in 50% of those Super Bowls, and they won 33% of them. Charging them with cheating might make those of us who grew tired of seeing them in the Super Bowl feel better, but somewhere deep in our heart (in an area no one will ever be able to see) we know it doesn’t explain that level of success sufficiently.

Hockey fans gave me one explanation about a decade ago. Hockey fans, not hockey insiders or analysts, but fans suggested that they thought their team had a better chance of winning in the coming year based on some of the hierarchical changes their team made in the offseason. I always knew, in the back of my mind, how important everyone from the general manager down to the scouts was, but I didn’t consider how institutional they were to the long-term success of my team.

A professional team in sports might have a few winning seasons here and there if they’re lucky enough to draft some key players and surround them with enough talent. They might even win a championship or two if the ball bounces the right way. If they don’t have the organizational structure of talented people throughout the hierarchy, they’re not going to win long term. As Jeff Benedict’s The Dynasty points out owners, general managers, talent scouts, and everyone in-between build a dynasty. The owner, in the case of the New England Patriots, Robert Kraft, was a businessman who had an obvious eye for talent. He also knew that after he found and hired that talent, his job was to back away and give them enough room to succeed. Some professional sports’ owners display too much micro level management (Jerry Jones), and some are too macro (Arthur Blank). As The Dynasty points out, Coach Bill Belichick made unpopular and jaw-dropping moves throughout the dynasty years, and Kraft didn’t approve of many of them, but he allowed his hire as coach/general manager to make whatever decisions he needed to make to sustain success. Those moves, more often than not, panned out over the long term.

A professional team in sports might have a few winning seasons here and there if they’re lucky enough to draft some key players and surround them with enough talent. They might even win a championship or two if the ball bounces the right way. If they don’t have the organizational structure of talented people throughout the hierarchy, they’re not going to win long term. As Jeff Benedict’s The Dynasty points out owners, general managers, talent scouts, and everyone in-between build a dynasty. The owner, in the case of the New England Patriots, Robert Kraft, was a businessman who had an obvious eye for talent. He also knew that after he found and hired that talent, his job was to back away and give them enough room to succeed. Some professional sports’ owners display too much micro level management (Jerry Jones), and some are too macro (Arthur Blank). As The Dynasty points out, Coach Bill Belichick made unpopular and jaw-dropping moves throughout the dynasty years, and Kraft didn’t approve of many of them, but he allowed his hire as coach/general manager to make whatever decisions he needed to make to sustain success. Those moves, more often than not, panned out over the long term.

One thing The Dynasty does not cover (because it’s probably of no interest to anyone but the football junkie) is the plethora of talent that Belichick and co., managed to find in the late rounds of the NFL Draft and in the various groups of undrafted free agents (UDFAs) that the Patriots hired. Were they lucky? Luck is involved of course, as even the best NFL scouts have a poor batting average, but the sheer number of successful moves the Patriots made in this regard that eventually paid off is an astounding comment on their long-term success. A number of my Patriot hating friends would love to claim that the Patriots might have been the luckiest team in NFL history in this regard. For twenty years though? I heard that Tom Brady once looked around the huddle of his teammates on offense and said, “How many of us are late round picks and Undrafted Free Agents (UDFAs)?” Look at the Patriots’ rosters throughout those 20 years. How many of their players on their roster were late round picks and UDFAs? Now, take that number and compare it to the rest of the NFL? The Patriots used multiple sources, both inside and outside the organization to inform their moves, but how many of those in-house advisers went off to other teams? How many of them were able to maintain that level of success picking players for other teams? Is it all about Belichick’s final say, or were Belichick and his coaches able to take those players to another level? How many of those same players went onto other teams to achieve the same level of success? How many coaches, from Belichick’s tree, went onto success with other teams?

If Belichick is such a genius, why didn’t he do it in Cleveland? What author Jeff Benedict points out in Dynasty is that Belichick couldn’t do what owner Robert Kraft did, Robert Kraft couldn’t do what Belichick did, and neither of them could do what Tom Brady did. The dynasty of the last two decades was a matter of stars aligning perfectly. If Robert Kraft didn’t buy the team, Tom Brady probably would’ve left the team after a few years, as he and Belichick didn’t see eye to eye on some matters and Kraft did everything he could to keep them together as long as possible. If Belichick remained a Browns or Jets coach, Robert Kraft’s Patriots might have won a Super Bowl or two, but six? If Brady went to another team, the Patriots might have won a Super Bowl or two, but six? Tom Brady might have won a Super Bowl on his own, but six of them? As The Dynasty points out, the Patriot dynasty was all about the stars aligning from the top down and a number of people played a role, but most of those people came and went, and the three most important players stayed for almost twenty years.

“Bunch of cheaters is what they are,” just about every Patriots hater says anytime the subject of Patriots’ long-term, sustained success over twenty years comes up. “Right on!” is what I’d love to say before giving that feller a mean, emotional high-five. I’d love to say that the reason the Patriots always beat my team is because they cheated in big ways and small ones, but it just seems too easy.

The Patriots were accused of filming the signals of the opposing teams’ defensive coordinators. An important note here is that the general practice of filming opposing coaches wasn’t illegal, but they couldn’t do it from their sidelines.

Another element of what we called Spygate is that the Patriots filmed the Rams’ walkthrough practice before 2002 in Super Bowl XXXVI. If you call filming a team’s walk-through practice, before a game cheating, then the Patriots allegedly cheated, but this opposing team’s walk-through practice occurred on the field, in pre-game warmups. That practice was available for everyone to see, and if the other team suspected the Patriots of being cheaters, why did they reveal secrets about their game plan on the field for all to see? They should suspect the Patriots of cheating. They should suspect every team of cheating and adjust accordingly. If this practice provided the Patriot’s enough information to win a game isn’t it on the opposing team to prevent the Patriots from learning their secret game plan. “It was against NFL rules for the Patriots to film that practice session.” True, but if this action led the Patriots to win even some of the games they did, then I have to wonder why my favorite team didn’t do it.

Another cheating scandal is Deflategate. Deflategate is quite simply a joke that Patriots’ that haters cling to to diminish the Patriots’ incomparable level of success. In both of these cases, the Patriots faced unprecedented scrutiny in the aftermath of the accusations, and in the case of Spygate, they went onto lose the Super Bowl thanks to a play some consider one of the best, most fluky plays in Super Bowl history. In the aftermath of Deflategate, they went onto win the Super Bowl.

The first thing Patriots’ haters and lovers, and all sports’ fans should admit is that we take some of these issues much too serious. Sports is a pastime. The literal definition implies that we are supposed to watch football to pass the time until the more serious things in life come along. The human being has been distracting themselves from the daily drama of their lives for centuries. Romans called it the bread and circus effect. As long as Romans were supplied food and entertainment to their people, the politicians could get away with whatever they want. How many Americans know every single detail of these controversies, versus those who know similar minutiae about local, state and federal politics? With that level of apathy, how far are is America away from the fiddling politicians of Rome that some suggest led to the fall of that civilization? When I witness two grown men argue over politics to the point that they almost come to blows, I can’t help but think of The Simpsons’ kids saying, “Are we there yet? Are we there yet?” on a car trip.

Bill Walsh

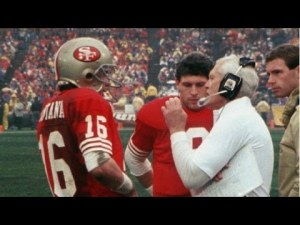

When it comes to professional football, we consider former 49ers coach Bill Walsh a genius among geniuses. Some place him up on the Mount Rushmore of the greatest NFL coaches of all time. Bill Walsh had a long and storied career coaching in the NFL and college, and he earned many of the accolades he achieved in his career. As another coach, Bill Parcells, once said, “You are who your record says you are.” Parcells also said, “Once you win a Super Bowl, no one can ever take that away from you.” No one can take Bill Walsh’s three Super Bowl rings away from him, and no one can deny that the man won 60.9% of his regular season games. He won 10 of his 14 postseason games along with six division titles, three NFC Championship titles, and three Super Bowls. He was NFL Coach of the Year in 1981 and 1984, and in 1993, and the NFL elected him to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

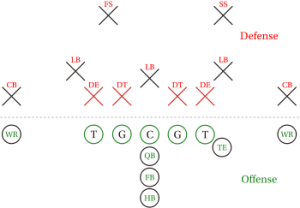

Bill Walsh headed a team while coaching the 49ers that selected some great players. A number of those players played in a number of pro bowls, and a number of them ended up in the Hall of Fame. Other than selecting Hall of Fame talent, some experts credit Walsh with developing the West Coast Offense, but he even admitted he based his system it on a system developed by Don Coryell, called “Air Coryell”. Still, Walsh took the influence, matched it to his talent on the field and won three Super Bowls and an overall winning percentage of 60.9%. Did Walsh coach those players up to the point that they were better than they were? Their winning percentage in the regular season and the post season, in a highly competitive National Conference, says yes. Walsh’s coaching tree also suggests he was a great leader. Walsh, like all great coaches, benefitted from talent, great advisers and scouts, and a whole lot of luck.

Bill Walsh headed a team while coaching the 49ers that selected some great players. A number of those players played in a number of pro bowls, and a number of them ended up in the Hall of Fame. Other than selecting Hall of Fame talent, some experts credit Walsh with developing the West Coast Offense, but he even admitted he based his system it on a system developed by Don Coryell, called “Air Coryell”. Still, Walsh took the influence, matched it to his talent on the field and won three Super Bowls and an overall winning percentage of 60.9%. Did Walsh coach those players up to the point that they were better than they were? Their winning percentage in the regular season and the post season, in a highly competitive National Conference, says yes. Walsh’s coaching tree also suggests he was a great leader. Walsh, like all great coaches, benefitted from talent, great advisers and scouts, and a whole lot of luck.

As for the talent he/they selected, no scout can guarantee that a college player’s talent will translate to the pro game. In that vein, we can say that selecting Joe Montana was something of a gamble. Yet, Joe Montana led Notre Dame’s 1977 team to a national championship. He was hardly a jewel in the rough. Another heralded move by Walsh was the trade for Steve Young. Steve Young’s talent didn’t appear to translate well in the NFL, as he had some poor years in Tampa Bay, and various NFL insiders deemed him a bust. With that in mind, we could say that Walsh’s trade involved something of a gamble, but Young finished his college career at BYU with the most passing yards in BYU history, he finished second in Heisman votes in his senior year at BYU, and he was selected number one in the USFL draft. He was hardly “a find” by Bill Walsh.

When it came time to select what some considered a true jewel in the rough, in the 2000 draft, to succeed the recently retired Steve Young, Walsh advised the 49ers to select Giovanni Carmazzi. Bill Walsh loved Carmazzi. He said he thought, “[Carmazzi] was a lot like Steve Young, only bigger.” Prior to the Carmazzi pick, Bill Walsh rejoined the 49ers front office and encouraged the 49ers to take Carmazzi with the 65th pick. Who, in the 49ers organization, would go against Bill Walsh? With the difficult transition from college to pro, it’s unfair to put a “miss” on any person’s resume, but imagine if Walsh “spotted” a starting quarterback from a power five conference who made numerous comebacks in his collegiate career versus a quarterback who some considered extremely raw from a Division I-AA school. Imagine what “spotting” Tom Brady would’ve done to Bill Walsh’s otherwise impressive resume.

To be fair to Walsh, many judged Brady almost comically lacking in athletic ability. He was the prototypical definition of a drop back, stay in the pocket quarterback and many believed the game was “now” so fast and the quality of offensive lineman was dropping so precipitously that every NFL now needed a quarterback with Steve Young’s athleticism. Walsh’s thought process probably accounted for that on both players when he encouraged the 49ers to select Giovanni Carmazzi with the 65th pick. (Giovanni Carmazzi never played a down in a regular season game.) Not that it matters, but the Brady family were 49ers’ season ticket holders for 24 years prior to the 2000 draft, and Tom Brady was a die-hard Montana, then Young fan, and the Bradys were hurt when the 49ers did not select the local boy from San Mateo. Brady was, at the very least, a hometown kid gone good in the California area. We have to imagine that his athletic accomplishments at Michigan put Tom Brady’s name in the 49ers draft room, and we can only guess that Walsh tired of the “Tom Brady conversation”.

Imagine if this genius among geniuses saw something most people missed in Brady, and his recommendations involved the 49ers going from Montana, as the starting quarterback, to Young, and then to Brady. Imagine if Brady accomplished half of what he did in New England for the 49ers organization. Those of us who loathed the 49ers in the 80’s and 90’s wouldn’t be able to tolerate the “genius among geniuses” discussions. This article wouldn’t be possible, because there would be no denying that Walsh was an unqualified genius. Had the Patriots not selected Brady, we can only guess that Brady loved the 49ers organization so much that he may have accepted just about any undrafted free agent contract offer from the 49ers.