If Elizabeth Holmes could’ve had an idea that worked, she could’ve been a contender, she could’ve been something real, and oh, the places she could’ve gone. The idea that we’re fascinated with this woman is obvious with all of the bios, documentaries, and news segments devoted to her. There are probably hundreds of different answers as to why, but I think it has something to do with the idea that her story is not a simple ‘person perpetuates fraud’ story.

Elizabeth Holmes was found guilty by a jury of her peers of perpetuating fraud. That’s a fact, and the glaring headline, and it might influence everything we learn about her story. Her story is just the latest in the ever-present, not-going-to-end-anytime-soon Cringe-TV. We love to laugh, cry, and scream in horror, but we also love to cringe. There’s probably something wrong with it, as we shouldn’t love it this much, but when someone gives all their money to a con artist, and then they convince their friends and family to give their money to them too, we cringe with excitement. Do we think we’re better than the victims? If we did, we wouldn’t develop crinkles (cringe wrinkles) during our obsessive binges. Our motive, when watching these shows is not to find out if the fraudsters did anything illegal, but how they did it.

Elizabeth Holmes was found guilty by a jury of her peers of perpetuating fraud. That’s a fact, and the glaring headline, and it might influence everything we learn about her story. Her story is just the latest in the ever-present, not-going-to-end-anytime-soon Cringe-TV. We love to laugh, cry, and scream in horror, but we also love to cringe. There’s probably something wrong with it, as we shouldn’t love it this much, but when someone gives all their money to a con artist, and then they convince their friends and family to give their money to them too, we cringe with excitement. Do we think we’re better than the victims? If we did, we wouldn’t develop crinkles (cringe wrinkles) during our obsessive binges. Our motive, when watching these shows is not to find out if the fraudsters did anything illegal, but how they did it.

After watching all of these shows, the viewing audience should ask themselves two questions. Did the 19-year-old sophomore at Stanford drop out of college to commit fraud, and if not, what did she know and when did she know it? Did Elizabeth Holmes want to become the next Steve Jobs so bad that she was willing to do anything to make that happen? Or, did that just kind of happen in the course of her troubled venture? Even though she was eventually deceitful, the idea that Elizabeth Holmes won over some of the intellectual glitterati of our nation is a testament to her talent, intelligence, and charm. She professionally seduced George Shultz, Henry Kissinger, David Boies, James Mattis, and, of course, Theranos Chief Operating Officer Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani. She also managed to secure $700 million in funding from the likes of Larry Ellison and Tim Draper. At its peak, her company Theranos, was valued at $9 billion.

Watching Hulu’s bio Dropout, HBO’s Inventor, the 20/20 news segment, or reading any of the web articles devoted to her story involves a battle between cringes and knee-jerk reactions. One knee jerk reaction we have is to now say Elizabeth Holmes was a con artist who engaged in fraudulent activity to secure funds from investors. We then dismiss her on that basis, but how many world leaders, politicians, and other charismatic, skilled, and deceptive people have attempted to pull the wool over the eyes of those luminaries listed above? Another knee-jerk reaction is to say that Elizabeth Holmes was a young, blonde woman who had obvious appeal to old, grey men. They might have enjoyed meeting with her. They might have enjoyed her attempts to professionally seduce them, but what happened when those meetings ended? A cadre of advisors probably sat down with the old, grey men and poured through her books, and they had a pro and con discussion with a George Shultz. He took their advice under consideration, and he ended up believing her. At one point in the story, Shultz even believed Holmes over his own grandson. How many years of experience did George Shultz, and all of the names listed above, have dealing with con artists and fraudsters? What does that say about them that they fell for Elizabeth Holmes’ deception, and what does it say about her? If she had a product that actually worked, imagine how real her success could’ve been.

Watching Hulu’s bio Dropout, HBO’s Inventor, the 20/20 news segment, or reading any of the web articles devoted to her story involves a battle between cringes and knee-jerk reactions. One knee jerk reaction we have is to now say Elizabeth Holmes was a con artist who engaged in fraudulent activity to secure funds from investors. We then dismiss her on that basis, but how many world leaders, politicians, and other charismatic, skilled, and deceptive people have attempted to pull the wool over the eyes of those luminaries listed above? Another knee-jerk reaction is to say that Elizabeth Holmes was a young, blonde woman who had obvious appeal to old, grey men. They might have enjoyed meeting with her. They might have enjoyed her attempts to professionally seduce them, but what happened when those meetings ended? A cadre of advisors probably sat down with the old, grey men and poured through her books, and they had a pro and con discussion with a George Shultz. He took their advice under consideration, and he ended up believing her. At one point in the story, Shultz even believed Holmes over his own grandson. How many years of experience did George Shultz, and all of the names listed above, have dealing with con artists and fraudsters? What does that say about them that they fell for Elizabeth Holmes’ deception, and what does it say about her? If she had a product that actually worked, imagine how real her success could’ve been.

The Theranos Corporation had a machine called the Edison, so named because lightbulb inventor Thomas Edison said, “I didn’t fail 10,000 times. The lightbulb was an invention with 10,000 steps.” How many careers were built out of try, try, and try again? Thomas Edison wasn’t excusing his failures. He was saying that he had to learn from the 10,000 misfires he made. Did Holmes’ Edison machine fail 10,000 times? “Who cares?” Holmes, Balwani, and all of the engineers and scientists could’ve answered. “Who cares if it fails 100,000 times. Imagine if we keep failing, and we learn everything there is to learn from those failures? Imagine if, one day, it works. We could transform the landscape.” The central question in this fiasco, to my uninformed mind, is is it possible that the Edison would have ever worked? If not, then we have beginning-to-end, no excuses, and full-fledged fraud on our hands, but what if Walgreen’s didn’t push for its arrival in their stores? What if Holmes and Balwani hadn’t pushed the engineers to make the Edison happen to satisfy Walgreen’s? Was it ever possible? Were the talented engineers and all of the employees they had on the payroll at Theranos for the money, or did they believe in Holmes’ dream?

The Hulu bio Dropout depicts biochemist Ian Gibbons, who served as the chief scientist of Theranos, complaining that the Edison “is just not ready” for Walgreen’s. He was the first experienced scientist Holmes hired, his name was on all of the patents, and from everything we read about Gibbons, he was more than a believer. He was one of the chief architects of Holmes’ vision. The portrayals of Gibbons on the 20/20 story, the Hulu bio, and the HBO documentary The Inventor, suggest he was never a naysayer. They suggest that he just set rigorous benchmarks for the product. He doesn’t say, at any point, that this was a fictional dream that Holmes concocted (as a Stanford professor did), that it’s a fraud perpetuated on investors and the public, or that it will never happen. With all of his experience in the field of biochemistry, Ian Gibbons believed in the product, but he said it was just not ready to meet Walgreen’s timeline. There was a certain duality to Gibbon’s pleas however. He needed a job. He was in poor health, and he needed the health insurance that Theranos provided.

The Hulu bio Dropout depicts biochemist Ian Gibbons, who served as the chief scientist of Theranos, complaining that the Edison “is just not ready” for Walgreen’s. He was the first experienced scientist Holmes hired, his name was on all of the patents, and from everything we read about Gibbons, he was more than a believer. He was one of the chief architects of Holmes’ vision. The portrayals of Gibbons on the 20/20 story, the Hulu bio, and the HBO documentary The Inventor, suggest he was never a naysayer. They suggest that he just set rigorous benchmarks for the product. He doesn’t say, at any point, that this was a fictional dream that Holmes concocted (as a Stanford professor did), that it’s a fraud perpetuated on investors and the public, or that it will never happen. With all of his experience in the field of biochemistry, Ian Gibbons believed in the product, but he said it was just not ready to meet Walgreen’s timeline. There was a certain duality to Gibbon’s pleas however. He needed a job. He was in poor health, and he needed the health insurance that Theranos provided.

What if they waited? Could they have waited? Would the money dry up if they delayed yet again? The stories of Elizabeth Holmes depict her as someone who had a natural gift for raising money. Could she continue to raise money at such a blinding pace, or were her chickens coming home to roost?

Now that we know Elizabeth Holmes was successfully convicted of fraud, our knee-jerk reaction is to believe that the whole venture, from beginning to end, involved a years-long series of deceitful acts. Suggesting otherwise insults our intelligence. The details of her ambition suggest this whole venture was narcissism as opposed to altruism. Now that we all know this was a fraud, we tint our rose-colored glasses with such a heavy dark tint that we can’t see anything else. Did Holmes believe in this idea, at one point, or was she so desirous of her own Steve Jobs image that she would do anything to get it? In that light, she’s rightly depicted as a narcissist, but did she wear black turtle necks and lower her voice to become the next Steve Jobs, or were these façades her attempts to have the world take a 19-year-old (or however old she was at the time) blonde seriously, so she could sell an altruistic product to the masses, to save lives?

In a fascinating, possible explanation of Elizabeth Holmes’ motivation for continuing “the lie”, behavioral economist Dan Ariely discusses a psychological experiment using a standard, six-sided die in the HBO documentary on this story The Inventor. In this experiment, the subject of the test is encouraged to predict the number of pips that will appear when the research scientist rolls the dice. One of the twists in this experiment is that the subject gets to pick the top or the bottom of the die, after the roll is complete. They keep that prediction, whether top or bottom, in their head. They don’t say it aloud. The scientists will give them a dollar for every pip on the die that appears with a correct prediction. If the number is one, they get one dollar, two for two, and six dollars if the number appears, top or bottom. In some cases, the die displayed one pip on the top and six on the bottom. “Which one did you pick?” the scientists ask, “The top or the bottom?”

“The bottom,” they said, when the six was on the bottom.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, I picked the bottom that time.” Boom, six dollars went into the subject’s pocket. In the next stage of the experiment, they are hooked up to a lie-detector to find that they lie some of the time to get the most money they can. The third part of their experiment involved charity. “All of the proceeds from a correct guess go to charity,” they informed the subjects. The scientists found that the subjects’ lies went up dramatically when the reward for their correct guesses went to charity.

If Elizabeth Holmes genuinely believe Theranos was an altruistic venture that would eventually help save lives, then what was the harm of a few lies here and there? We all lie, and most of us lie for narcissistic reasons. What if we genuinely believed we could revolutionize the world, and as Holmes continually suggested we could spare our proverbial brothers and sisters from having to say goodbye to the world too soon? Would we fudge the numbers, lie to investors, and treat obnoxious employee questions the way Theranos did if it could buy a little time to see our dream actually come true?

If Elizabeth Holmes genuinely believe Theranos was an altruistic venture that would eventually help save lives, then what was the harm of a few lies here and there? We all lie, and most of us lie for narcissistic reasons. What if we genuinely believed we could revolutionize the world, and as Holmes continually suggested we could spare our proverbial brothers and sisters from having to say goodbye to the world too soon? Would we fudge the numbers, lie to investors, and treat obnoxious employee questions the way Theranos did if it could buy a little time to see our dream actually come true?

Elizabeth Holmes was told that this will never work by one of the Stanford professors she approached with her the idea. Our knee-jerk reaction, knowing what we know now is, why didn’t she listen? How many ingenious minds are told such things at the outset? Then we learn that another esteemed Stanford professor compared her to Mozart, Beethoven, Newton, Einstein, and da Vinci. Others said she might be the next Archimedes.

Elizabeth Holmes had a childhood fear of needles, and she thought the products she and her team created at Theranos could spare future sufferers of this fear. She also thought that she could transform the medical industry. At some point, her dream ran into reality, which begs the old Watergate question: “What did she know, and when did she know it?” When she encountered Edison’s 10,000 failures with the Edison machine, she pushed on. Why did she push on? Did she believe in this machine, and this dream, that much? Or, was she in too deep? The cringe takes hold when the main character not only continues to lie, but she doubles down. “Why would you do that?” our cringe asks. “When it’s plainly obvious that you’re trying to swim out of a sand hole.”

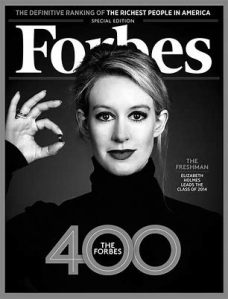

How much pressure was Holmes under at this point? She had 800 employees counting on her, numerous investors, and friends and family counting on her to make this happen? She appeared on the cover of Forbes, Fortune, Bloomberg, and Inc. Magazine. She appeared on CNBC a number of times, spreading her gospel. How many of us could experience this level of adulation, coupled with the pressure that it entails, and say, “All right, well, we’ve failed ten thousand times, over the course of ten some odd years, and well, it looks like this thing doesn’t work, and it never will. Everyone can go home now. There’s nothing more to see here. We’re folding up shop folks, it’s now time to go home.”

In the midst of our knee-jerk reactions and hours-long cringes, we turn to our wives and say, “At that point, right there, I would’ve been more forthcoming.” To which, our wife should’ve said, “And then what?” And then, after you’ve cleared your name of any fraud by declaring the dream over, everything is over. Everyone you know and love realizes that you’re not the golden child they thought you were yesterday. You’ll become a punchline, as everyone you know will begin to mimic and mock your forthcoming statement, and the life you knew for ten-plus years is over as you spend the rest of your life realizing that you peaked at thirty-years-old.

Among the top CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, there is one characteristic common among them an uncommon belief in self. If Holmes shared this enviable trait, as many suggest she did, she believed she could overcome any obstacle before her, and to do so there are times when we might have to fudge and fib a little to encourage the skeptical and skittish around to trust our unwavering vision just a little bit longer? An edited number here and there to encourage the legions of media members and employees who worshipped you will mean nothing when this product finally reaches completion. When Theranos employees on the ground floor begin to ask questions, it’s fine, as long as they don’t discourage their fellow employees and spread poor morale. As long as they don’t violate their NDAs and speak to the press or their family and friends, we’ll be fine. Plus, forcing employees to sign NDAs is a common practice in Silicon Valley and the rest of the business world. Furthermore, the best CEOs learn to lean on some level of obfuscation to sidestep deep, penetrating questions regarding initial results of products during their gestational period. Did Elizabeth Holmes have an unwavering and uncommon belief in herself or her products, in a manner those in sales will say are one and the same?

***

“I’m not going to fall for this,” we say when we click on the app to watch an episode of Cringe-TV. We know the perpetrator has been convicted, and we know some of the details of the case, but we want to see the suffering. We want to see the faces of the people who were duped, and we want to laugh at them when they confess the extent of the betrayal went from hundreds to hundreds of thousands, and if we’re really lucky, we’ll see the face of that poor sap who dumped millions. We might see something wrong with us for enjoying it so much, but we keep watching.

I just can’t wrap my arms around Elizabeth Holmes being a fraudster from beginning to end. As a former fraud investigator, I know she’s been convicted of fraud by a jury of her peers, but I can’t help but think Elizabeth Holmes believed in her idea for a majority of those twelve years and presumed 10,000 failures. I know many of the facts of the case, but I would love to know what happened to her when it became obvious that her products were never going to work. Did she and her team switch to Siemans’ products, and all of the other measures she used to allegedly defraud victims, or was she desperately seeking more time. Or did she fear that “What then?” question if she was totally forthcoming at some point.

Fraud is perpetuated throughout our country on a daily basis from Silicon Valley to Bangor, Maine. How many of these acts are committed for purely narcissistic reasons, and how many of these paths are paved with altruistic intentions? We might never know what was going on in Elizabeth’s head throughout the trials and tribulations she experienced, and our knee-jerk reaction is to shut down all discussion on the matter with the fraud conviction, but think about what an incredible person Elizabeth Holmes could’ve been if she devoted all of the energy, talent, and intelligence that impressed so many luminaries of our society into something that actually worked.

The other side of the coin, the elephant in the room that no one wants to discuss is that Elizabeth Holmes was a woman. Going through all the interviews of her investors, and all the luminaries who invested in her company, I couldn’t get that fact out of my head. Elizabeth Holmes was obviously charismatic, she had a excellent work ethic, oodles of talent, and she had unwavering belief, but would all these people, including the financial magazines who had her image on the cover of all of their magazines, have fallen for her claims if she was a regular forty-something male CEO making substantial and exciting claims? We can only speculate, of course, but I think the idea that she was a woman relaxed some concerns. They wanted her to succeed, and they wanted to be the ones who were so open-minded that they didn’t want to be the type to speculate that her claims were just unrealistic, because that might subject them to the “Are you saying all this, because she’s a woman?” charge. We’ll never know, of course, but I have to think that a regular fella wouldn’t have received the benefit of doubt.