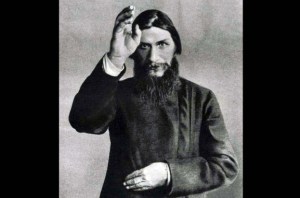

“Was Gregori Rasputin really an occult mystic who used treacherous sorcery to ingratiate himself to Tsar Nicholas II by performing miracles on and curing the pain of the Tsar’s son? Or was he, no less impressively, a most gifted Counter-Agent who disarmed his country’s most powerful rulers through sheer charisma and manipulative charm?” –asks Adam Lehrer in the Safety Propoganda.

“No!” say some historians. “Rasputin wasn’t any of those things. He was nothing more than a right time, right place charlatan.” Anytime one accuses another of absolute fraud, deceit or corruption, their first responsibility is to prove that the provocateur knowingly deceived. We can all read the conditions of the Russian empire at the time and see that they were susceptible and vulnerable to a charlatan. We can read through the health conditions of Tsar Nicholas II’s son, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, and know that the Romanovs were desperate for a miracle worker to spare him the pain and possible death of hemophilia. We can take one look at Rasputin, the ill-educated peasant from nowhere, Russia and know that if he didn’t do something spectacular, he was doomed to a life of anonymity, but there is ample evidence to suggest that Rasputin believed he had an ability, if not the otherworldly powers, to cure the Tsar’s son. To believe otherwise is to suggest that Rasputin knowingly deceived his family since birth, and the friends and neighbors who surrounded him in the early part of his life. There’s an old line on subterfuge that it’s not really a lie if you believe it. When we say this, we usually do so tongue in cheek, but Rasputin’s bio suggests that he truly believed he had God-like powers? “Christ in miniature,” Rasputin often said when asked to characterize himself. Was he a deceptive person? Did he attempt to deceive the Empress Alexandra, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich’s mother, to weave a way into the empire, or did he attempt to prove to himself as “The Chosen One!”

“No!” say some historians. “Rasputin wasn’t any of those things. He was nothing more than a right time, right place charlatan.” Anytime one accuses another of absolute fraud, deceit or corruption, their first responsibility is to prove that the provocateur knowingly deceived. We can all read the conditions of the Russian empire at the time and see that they were susceptible and vulnerable to a charlatan. We can read through the health conditions of Tsar Nicholas II’s son, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich, and know that the Romanovs were desperate for a miracle worker to spare him the pain and possible death of hemophilia. We can take one look at Rasputin, the ill-educated peasant from nowhere, Russia and know that if he didn’t do something spectacular, he was doomed to a life of anonymity, but there is ample evidence to suggest that Rasputin believed he had an ability, if not the otherworldly powers, to cure the Tsar’s son. To believe otherwise is to suggest that Rasputin knowingly deceived his family since birth, and the friends and neighbors who surrounded him in the early part of his life. There’s an old line on subterfuge that it’s not really a lie if you believe it. When we say this, we usually do so tongue in cheek, but Rasputin’s bio suggests that he truly believed he had God-like powers? “Christ in miniature,” Rasputin often said when asked to characterize himself. Was he a deceptive person? Did he attempt to deceive the Empress Alexandra, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich’s mother, to weave a way into the empire, or did he attempt to prove to himself as “The Chosen One!”

At the moment of his birth, Rasputin’s mother believed he was the chosen one, and we can guess that she told him as much on a daily basis throughout his youth. We might cut her some slack for this fantastical notion, seeing as how Rasputin may have been her only child of seven, or eight, to survive childhood. (Evidence suggests she had a daughter who may have also survived for a time.) Anytime a mother has a child, they consider that child special, but in Rasputin’s Serbian village of Polrovskove death among children was so common that the miracle we know as childbirth was increased tenfold in that world of peasants. The idea that Rasputin was special may have grown in her mind as he did, until she was convinced that Grigori was a gift from God, and she eventually made a crossover to the idea that her son was the chosen one.

What would we think if our mother told us we were God’s messenger throughout our youth? What if she bolstered her claim by telling us that at the moment we were born a rare celestial event occurred to mark the occasion of our birth. “A shooting star of such magnitude that had always been taken by the God-fearing muzhiks as an omen of some momentous event,” she said. When historians say Rasputin fell into a right place, right time era, they’re talking about an era that followed executions for anyone who attempted the heretical notions Rasputin espoused to a time when minds were just beginning to open up to the idea that man could manipulate his surroundings for the purpose of massive technological advancement. Those from the era also learned, mostly secondhand, of some of the advancements made in medicine that suggested man could wield God-like powers over life and death in a manner deemed heretical in previous eras. The early 20th century Russian citizen was likely more amenable than ever before to the belief that man could now manipulate the bridge between life and death, and generally make life better for his fellow man without necessarily being a heretic. Based on that, we could say that Rasputin was a right time, right place charlatan, or we could say he, more than any other, took advantage of this window in time. Those who call him a charlatan, however, must still address the notion that Rasputin knew he wasn’t the chosen one, and that he was lying to the vulnerable, desperate Empress Alexandra Feodorovna (Alix of Hesse) to convince her that he was. How did Rasputin discover that Tsar Nicholas II’s son, Tsarevich Alexei Nikolaevich was sick? The Russian empire, in the era of the Romanovs rule, was a vault. No state secrets, or leaks, found their way out, and the illness of the Tsarevich was one of the most guarded secrets. The Romanovs had nothing to gain by announcing their only male heir’s illness and everything to lose. Through the connections he made, as a man “known to possess the ability to heal through prayer” Rasputin was called upon to heal the Tsarevich by Anna Vyrubova, the empress’s best friend. Did Rasputin struggle with this newfound information, did he consider it his patriotic duty to try to save the young heir to the throne, or did he see this as an opportunity to finally prove himself to himself? If he failed to convince his family, friends and neighbors of his special powers, there was nothing lost. If he was a fraud, and he knew it, he would surely have a list of excuses he could use to explain it. If he failed the Empress, the embarrassment of trusting the health of her only begotten son to a lowly peasant could lead the Empire to try to silence any fallout by imprisoning Rasputin or executing him, and needless to say, this empire had no moral qualms executing peasants. Failing the empire, at the very least, would ultimately reveal to Rasputin and everyone else in the empire that he was a fraud and a charlatan. This presumed struggle goes to the heart of this article, because Rasputin eagerly accepted the invitation to try to heal Alexei. Some argue that Rasputin may have been so familiar with hemophilia that he knew certain techniques he could use to help calm the Tsarevich down, and thus give the illusion that he was cured. We still consider it something of a miracle that our body often manages to heal itself. Some call it the power of the mind, others call it the power of prayer, and still others call it the mysterious power of the miraculous machines in the human body to heal itself. No matter what we believe, it appears that in some cases, if our mind believes we are being cured, it can go a long way to encouraging us that we are. No matter the arguments, details, and conclusions, Rasputin did it. Rasputin did what the most brilliant minds of medicine in Russia, in the early 20th century, could not, and when he advised Alexandra on how to maintain Alexei’s health, and that advice proved successful, Alexandra fell under Rasputin’s spell. She thought he, more than any of the other men of medicine in the empire, could cure her son of a malady to which her side of the family was genetically susceptible. The idea that she believed Rasputin could cure her son, led her to convince her son of it, and that presumably led Alexei calming to the point that his hemophilia was not as debilitating as it would’ve been otherwise. So, Rasputin did help provide what Alexandra considered a miracle, but our modern understanding of the relationship between body and mind suggests that it was not as mystical or unprecedented as Alexandra and those who love the narrative want us to believe. The interesting nugget here, and the import of this story, is that Alexandra may have followed Rasputin’s advice on how to cure her son so often that she may have also followed his other advice on greater matters of the Russian Empire, and she may have whispered that same advice into Tsar Nicholas II’s ear as if it were her own. We’ll probably never know the truth of any of this, because the Romanovs had a situation in their empire where they were able to control their narrative. They had very little in the way of leaks, and no one from the empire wrote a tell-all after the empire collapsed to detail what really happened within the confines of its walls. It was a situation modern politicians would salivate over, but historians, not so much. As a result of the tight Romanov ship, most of the literature written about this Russian era and the relationship between Rasputin and the Romanovs involves a great deal speculation. That’s the fun part for the rest of us, because we can use the base details of what happened and submit our own subjective beliefs into the story for fantastic and fantastical conclusions. One of us can speculate that Grigori Rasputin was a sorcerer with otherworldly powers, another can say he was an absolute charlatan, and the rest of us can say that the man landed in the perfect time and place for nature of his actions are almost impossible to prove or disprove. The one thing we can state without fear of too much refutation, is if we took all of these ingredients and threw them into a big stew of rhetorical discussion, is that Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin was one of the most enigmatic figures in world history.  What if everyone we knew and loved growing up believed, as our mother did, that we were gifted with the ability to read minds, and/or “see things that others could not”. Rasputin grew up in a climate where everyone he encountered on a daily basis, and presumably throughout his life, believed he had divine powers. If we marinated in the thoughts of our own divine nature throughout our youth, how many of us would end our believing it? Our parents are powerful influences on our lives, and how we think, but as we age, we begin to see the errors of their ways. If Rasputin went through this natural course of maturation, his friends and neighbors in Polrovskove only bolstered his mother’s claims. Rasputin was also involved in a death-defying accident that took the life of his cousin. He spent years wondering aloud why he was spared and his cousin wasn’t. His conclusion, one which we can assume that his friends and family encouraged, was that divine intervention spare him, so he could go out and spread God’s message.

What if everyone we knew and loved growing up believed, as our mother did, that we were gifted with the ability to read minds, and/or “see things that others could not”. Rasputin grew up in a climate where everyone he encountered on a daily basis, and presumably throughout his life, believed he had divine powers. If we marinated in the thoughts of our own divine nature throughout our youth, how many of us would end our believing it? Our parents are powerful influences on our lives, and how we think, but as we age, we begin to see the errors of their ways. If Rasputin went through this natural course of maturation, his friends and neighbors in Polrovskove only bolstered his mother’s claims. Rasputin was also involved in a death-defying accident that took the life of his cousin. He spent years wondering aloud why he was spared and his cousin wasn’t. His conclusion, one which we can assume that his friends and family encouraged, was that divine intervention spare him, so he could go out and spread God’s message.  The arguments about what Rasputin did to eventually calm the conditions of Alexei Nikolaevich are wide and varied, but most historians agree that Alexei was never cured of his case of hemophilia, because there is no cure. To this date, modern medicine has yet to find a cure. Alexei had hemophilia the day he was born, and he had it when he was murdered, a month before his fourteenth birthday. The very idea that he almost made it to fourteen, and he could’ve lived well beyond that, had he not been murdered, was viewed as one of a series of Rasputin’s miracles. The fact that Alexei was relieved of his pain, and many of the symptoms of hemophilia, was also viewed as one of Rasputins’ miracles.

The arguments about what Rasputin did to eventually calm the conditions of Alexei Nikolaevich are wide and varied, but most historians agree that Alexei was never cured of his case of hemophilia, because there is no cure. To this date, modern medicine has yet to find a cure. Alexei had hemophilia the day he was born, and he had it when he was murdered, a month before his fourteenth birthday. The very idea that he almost made it to fourteen, and he could’ve lived well beyond that, had he not been murdered, was viewed as one of a series of Rasputin’s miracles. The fact that Alexei was relieved of his pain, and many of the symptoms of hemophilia, was also viewed as one of Rasputins’ miracles. “What was he?” “Who was he?” “What exactly did he do to spare the life of the Tsarevich?” “Was he the most gifted sorcerer the world has ever known?” How great was his influence over Alexandra? Reports suggest he had no influence over Nicholas II, but Alexandra did. Did Rasputin whisper things in Alexandra’s ear that she whispered into Nicholas II’s, as if they were her own ideas. British intelligence believed this, and some suggest that the Britain commissioned Rasputin’s murder, because they feared his influence in the Romanov Empire might prevent Russian entry into World War I?

“What was he?” “Who was he?” “What exactly did he do to spare the life of the Tsarevich?” “Was he the most gifted sorcerer the world has ever known?” How great was his influence over Alexandra? Reports suggest he had no influence over Nicholas II, but Alexandra did. Did Rasputin whisper things in Alexandra’s ear that she whispered into Nicholas II’s, as if they were her own ideas. British intelligence believed this, and some suggest that the Britain commissioned Rasputin’s murder, because they feared his influence in the Romanov Empire might prevent Russian entry into World War I?