When I first saw Charles John Klosterman had a new book coming out about the The Nineties. I knew he would devote space, for too much space, to Nirvana’s album Nevermind. Klosterman’s essays and books cover a wide array of topics, but his primary focus has always been music. As such, we can call him a music critic without feeling too much guilt about limiting his curriculum vitae (or CV). As a music critic, Klosterman is professionally required to one superlative per every one hundred words. His awareness of this is quota is illustrated by various attempts to qualify his superlatives with qualifiers. The problem with this exercise is that he uses superlatives in conjunction with qualifiers so often that reading a Klosterman book can become a literal exercise in the form of mental jumping jacks.

Some readers might view an Klosterman’s excessive use of superlatives as silly, but others might view the practice as the author making bold statements. If, that is, the author can back them up, and Klosterman does. Most readers, whether they agree or not, also view it as better reading when an author litters his narrative with bold statements. As my 8th grade teacher once told me after failing an opinion piece of mine, “If you’re going to be wrong, be wrong with conviction.” The problem with superlatives is that most authors feel compelled to address subjective tastes with qualifiers. I write this for those readers who might have a tough time making it through their jumping jacks.

The best way to call Nevermind the greatest album of all time, as Klosterman does, is to say everything but. This literary device allows the author to load their but with supporting evidence to allow the reader to reach their own conclusions. Yet, those of us who read music critics, like Klosterman, on a regular basis, can’t help but think Nevermind is overrated. Most of us think it was a fantastic and transcendent album (I can’t remember meeting anyone, even those in the “sellout” crowd, who told me they thought the album sucked, but I’m they’re out there). Reading music critics, however, Kurt Cobain walked up Mt. Sanai and came down with these thirteen songs.

Klosterman qualifies his superlatives in his first essay on Nevermind, saying, “The video for Smells Like Teen Spirit was not more consequential than the reunification of Germany. But Nevermind is the inflection point where one style [heavy metal] of Western culture ends and another begins.” Once he gets that humorous qualifiers out of the way, Klosterman writes that “In the post Nevermind universe, everything had to be filtered through the notion that this specific representation of modernity was the template for what everyone wanted from everything, and that any attempt to understand young people had to begin with an understanding of why Nirvana front man Kurt Cobain looked and acted the way he did.”

This theory reminded me of a conversation I had with my uncle’s friend on the weekend after John Lennon was killed. I was not yet a teen, and this guy was well into his forties. As such, he had his finger on the pulse of the culture surrounding John Lennon far better than I did. When he said, “The man changed the world,” he said that to defend Lennon against the charge I made that Lennon was nothing more than a rock star. Even at that young age, I knew Lennon was a significant figure in our culture, but I thought the media attention devoted to the man was a bit over the top. “We were all asleep before John Lennon,” he added. “He woke us up.”

This theory reminded me of a conversation I had with my uncle’s friend on the weekend after John Lennon was killed. I was not yet a teen, and this guy was well into his forties. As such, he had his finger on the pulse of the culture surrounding John Lennon far better than I did. When he said, “The man changed the world,” he said that to defend Lennon against the charge I made that Lennon was nothing more than a rock star. Even at that young age, I knew Lennon was a significant figure in our culture, but I thought the media attention devoted to the man was a bit over the top. “We were all asleep before John Lennon,” he added. “He woke us up.”

“Really?” I asked. “He affected your life that much?” He maintained it did.

I lost a lot of respect for my uncle’s friend when he said that, for even then I had a tough time understanding how a rock singer, or any entertainment figure, could alter an individual’s philosophy to such a degree that it changed how they react with people, and the way they lived their life. As I’ve grown older, I realized some people read too many music critics and watched too many retrospective shows with cultural doyens dropping such bromides. The latter often occurs after the tragic death of a cultural icon, and we all rewrite our past to fit that narrative.

As if to address this issue, Klosterman quotes Larry McMurtry’s Walter Benjamin at the Dairy Queen. “I suspect that [Walter Benjamin] would be a little surprised by the extent to which what’s given us by the media is our memory now. The media not only supplies us with the memories of all significant events (political, sporting, catastrophic), but edits these memories too.”

The media permits us to touch the touching sentiment of the moment, so that we might become part of it. We remember where we were when we first heard the news. “I was eating a chili dog at the Dairy Queen that was just three blocks from my home, when a fella in knit cap told me that John Lennon was shot. I’ll never forget that cap. It was blue with a yellow line on it. He also had a beard similar to the one Lennon wore in his solo years. It was almost eery.”

We repeat the lines media figures and figurines say and write with their king of the mountain characterizations of iconic figures and figurines to impress their peers, because we want to be their audience. We also want to be the writer writing to other writers, and we do so by speaking in superlatives to suggest we understand profound greatness. Common, every day people turn to their friends and say things like, “The voice of a generation, he woke us up, and I think about him every day.” We talk about his music changed our life, and how we’ll never be the same. These are touching sentiments that we might mean in the moment, but they’re enhanced by the media, and ultimately untrue.

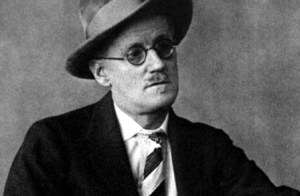

I tried to establish a link with an impressive individual I met. The best way to do that, I thought, was to relay whatever information I had about his hometown, Dublin, Ireland. I mentioned that I read most of Ulysses, and I added the joke, “I’ve probably read as much of that book as anyone has.” That joke played on the Larry King quote, “Everyone I know owns Ulysses, but no one I know has finished it.” The impressive individual looked confused, but I didn’t realize how confused he was, until he said:

“Is that a book?”

“Well, yeah,” I said completely thrown off, “by James Joyce?”

“Never heard of him,” he said.

“The author,” I said. He shrugged. “You’ve never heard of James Joyce?! I thought he was the most famous Dubliner this side of Bono. Don’t they have statues built for him in the town square?” Nothing.

This lifelong resident of Dublin had never heard of someone I considered one of his city’s top five most famous residents. After all my reading on Joyce, I considered it impossible that a Dubliner had never heard of him. I considered it the cultural equivalent of an American never hearing the name Babe Ruth. I realized that I fell prey to cultural insiders writing to impress fellow insiders. I love reading Klosterman, but this, too, is his motif.

To Klosterman’s credit, he does qualify his superlatives at the beginning of the essay, writing, “The songs on Nirvana’s Nevermind did not tangibly change the world. There are limits to what art can do, to what a record can do, to what sound can do.”

After submitting that qualifier, he writes, “Nevermind changed everything.” (Perhaps in an intangible way?) He focuses this thesis on advertising, specifically an ad that involved Subaru’s introduction of the Impreza. Klosterman concludes that Subaru’s spokesman in the ad had to “talk about Nirvana without talking about Nirvana,” because “Nirvana would have never participated in a car advertisement.” Klosterman basically admits that the pairing would’ve been disastrous if it happened, but he doesn’t explain why. He simply contributes to the narrative Cobain parlayed with the “corporate magazines still suck” T-shirt he wore on a Rolling Stone cover.

I have no doubt that if Subaru approached Cobain, he would’ve laughed it off. Cobain gave us no reason to believe he was into the whole corporate sphere, and for the most part, he never wavered from the punk ethos. (Though he did force his bandmates to sign over most of the writing credits for Nirvana’s music. We should have no problem with that, since by all accounts Cobain wrote the lyrics and most of the music, but that action doesn’t align with the “One for all and all for one” Three Musketeers, punk ethos.)

What if the Subaru proposal hit Cobain’s desk at Nirvana Inc., and Cobain was all about it. “Punk ethos be damned, look what they’re offering to pay me for a couple hours of work.” His business partners would’ve informed him that this move would not only irreparably damage Cobain’s image, but everyone involved and the legacy they were creating. “This will force your fans to defend the Subaru ad for the rest of time,” a member of his management team, probably named Todd, would say, “and I don’t care how much they’re paying you, your bottom line will be affected long-term.”

Klosterman does admit that Nirvana (without singling Cobain out) made “conscious choices in order to become the most popular band in the world,” but Klosterman still feels the need to write “Nirvana would have never participated in a car advertisement.”

One particularly obnoxious and useless complaint I have is Klosterman repeating the line, [Kurt Cobain] “didn’t know” about a company putting out a deodorant called Smells Like Teen Spirit. By writing this open-ended line, Chuck Klosterman contributes to a fable on par with “I cannot tell a lie. I did chop down that cherry tree” or every president in the last thirty years telling a reporter, “I haven’t read the report in question.”

Klosterman relays the story of how a girlfriend (Kathleen Hanna) of one of Kurt’s girlfriends wrote, “Kurt smells like teen spirit” on his wall in lipstick. This was her note to Kurt and the girlfriend that informed them she was onto the fact that they were involved romantically. Now, it’s plausible that Kurt thought the lipstick message referred to the general smells of sex, but Kurt was a writer, and her message obviously inspired him. If he was so inspired to write a song about it, wouldn’t he say, “That’s hilarious, but what did you mean by it?” to Kathleen Hanna. If that didn’t happen, wouldn’t his friends ask him what it was about? If he told them what he thought it meant, wouldn’t they correct him, if he thought it was about the smell of sex? “No, what Kathleen Hanna was saying was your girlfriend uses a deodorant with the brand name Smells Like Teen Spirit, and the fact that you smell like that deodorant means she knows you’re having sex with her friend.”

If the origin of the message managed to escape his friends, family, and all of the small venues he played in to test the material out, wouldn’t someone in his band or any of the teams of people involved in the production process of the album inform him of the name of the deodorant before they released it?

Michael Azzarad writes Cobain claimed that he thought Kathleen Hanna’s message was in reference to “the conversation we were having, but … I didn’t know the deodorant spray existed until months after the single came out.” I’ve never been involved in the process of a song, granular to final press, but I can only guess that in the 90’s, a song passed through hundreds to thousands of ears before final production.

My thoughts, for what they’re worth, are that so many people hit Cobain from so many quarters that he asked for help. I imagine Cobain saying something like. “I love the name of the song so much, and I’ve tried to come up with other titles, but none of them feel as right. How do we escape this unfortunate tie-in that everyone goes on and on about? I can’t play it anywhere without someone telling me about that damned spray.”

To which, a friend or a management type, probably said, “Just feign ignorance.”

“But they’re not going to stop asking about it.”

“They’re not, but when they do, just maintain that you didn’t know. Don’t include a timeframe. Just leave that comment open-ended, because it’s true, you didn’t know for a time. No one is going to ask a “What did he know, and when did he know it?” question about the name of a song. Nobody’s going to care that much.”

Did George Washington chop down a cherry tree, did Led Zeppelin sell their souls to the devil, did Kurt Cobain know about the similarities between the name of his most famous song and a deodorant’s brand name, and did he seek fame and fortune?

On the latter, I suspect that Cobain wanted to make the best album possible, and he allowed some corporate guys to do whatever they had to do to make Nevermind as great as it could possibly be. Some, including Cobain, say that something was lost in the mixing process. So, why did he do it? Why did Cobain succumb to the pressure from label execs and permit Andy Wallace to master it with what some call an “airplay-inviting varnish”? I’ve read that many in his inner circle were against it, and Cobain later regretted it. To understand why he did it, we probably need sort through some deep psychoanalysis of Kurt’s past and present, but that would likely be so far off base that it’s not even worth trying. Some of those who were close to Kurt in the present tense of Nevermind’s pre-production and production, suggest he wanted it more than they will ever tell you. What is it? We don’t know, but I believe Kurt when he said he never wanted to be famous, and I don’t think he ever strove to be rich beyond his wildest dreams, but I have to imagine that he wanted greatness bestowed upon him by his peers first and foremost, rock critics and journalists, and us. I don’t think he necessarily wanted or needed the spoils that come with it however.

All theory and analysis is autobiographical, as I wrote, and most of it is probably wrong, but the one thing we do know is Kurt Cobain, and Nirvana, wrote one hell of an album. Did the iconography of Kurt Cobain lead to rock critics, like Chuck Klosterman, using so many superlatives that Nevermind is now overrated? Perhaps. If Cobain’s worldview didn’t align so well with most of the rock critic world, they might have had a different take on his music. If the timing of the release of Nevermind was different, and it didn’t change the face of music (allegedly, single-handedly), would it have been regarded with such superlatives? Ifs and what if are for children, however, and when we wipe away all of it, and the myths, the narratives, and iconographic worship of Kurt Cobain, we still have to admit he and Nirvana wrote one hell of an album. On that note, Chuck Klosterman wrote one hell of a book, containing essays on Nirvana, 911, and other matters. His book on The Nineties is chock full of deep, entertaining insight into what made that decade what it was, and the reverberations that the decade sent down (or up?) to the modern era.