“If you love that book on Van Gogh that much, you should try reading Walter Isaacson’s Leonardo da Vinci,” I told a person who was pitching a Vincent Van Gogh book to me. I normally don’t care for people who say, “You think that’s great, you should try this,” but I was so enamored with Isaacson’s book that I couldn’t keep quiet about it.

“At some point in his younger years, da Vinci probably saw someone paint most beautiful eyes he ever saw. At some point, he probably saw someone paint the most enigmatic smile ever created, and he had to top them,” I said. “Either that, or he saw the extent of his talent at some point in his life, and he wanted to go deeper to better understand what he wanted to portray.

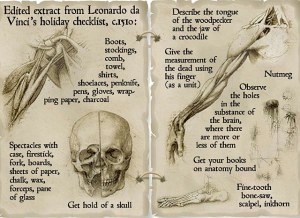

“However he arrived at this point, Leonardo da Vinci became an artist who could no longer just paint a smile. He couldn’t just paint eyes. He wanted, needed, to understand the inner machinations of the muscles and tendons involved in the smile and the mechanics of the eye to make them appear as alive and realistic as possible. Due to constraints of his era, he had to hire grave robbers to exhume bodies for him (some suggest he ended up carving up thirty bodies), so he could dissect them to help him understand our anatomy on a deeper level to understand how these components of our face worked together to form something as complex as a smile. In the early years of this pursuit, the grave robbing had to occur under the cover of night, because it was deemed illegal by the Catholic Church to dissect a human body, unless it was being performed by a qualified physician.

Da Vinci had to go deeper into channels that you and I would never consider to perfect his brand of visual manipulation that might lead us believe that the eyes were following us around a room. Leonardo’s methodology was that the difference between a talented artist, and one who seeks perfection is not the big things, it’s all the little, insignificant things that you and I would never consider. “It is necessary for a painter to be a good anatomist,” da Vinci wrote, “so that he may be able to design the naked parts of the human frame and know the anatomy of the sinews, nerves, bones, and muscles.”

“Oh my gosh,” my Vincent van Gogh loving friend said. “I had no idea, and I’m an art enthusiast. I’ll bet most people who haven’t read that book don’t know that.”

“His work on these cadavers was in service of his art,” I added, “but he became so obsessed with it that my guess is that much of what he uncovered was useless to him professionally. He might have started this process in service to his art, but I’m guessing that his curiosity overwhelmed him when he started finding answers. I’m guessing that he carved up the first cadaver to find an answer, then he found it, and he dug deeper and found other answers to questions he never asked before. He found some answers to irrelevant minutiae that intrigued him so much, and he became so obsessed that he probably forgot the original reason he paid the grave robbers to exhume bodies, and he became less of an artist seeking answers to artistic questions and more of a scientist.”

The latter was an opinion that Isaacson would correct. “Da Vinci was never less of one or more of another. He sought to infuse science and math into his art. From the anatomical perfection he sought in the Mona Lisa to the mathematics of perspective he used in The Last Supper, da Vinci was always seeking a hybrid of the three.”

“The point,” I would counter, “is there had to be a point of origin for his fascination with science and math. If there wasn’t, if he was always fascinated with science and math, there had to be a point where he decided to incorporate these disciplines into his grand visions of art. I understand that he eventually achieved a hybrid, but there had to be a point where he said if I’m going to realistically portray water flow, I need to gain firsthand experience and knowledge. In doing so, he was so fascinated with his findings that he forgot to complete the paintings he was commissioned to complete.”

Some say that Leonardo da Vinci was such a curious person that he made it his goal to ask himself one hundred questions a day. You’ll note that it wasn’t necessarily his goal to find one hundred answers a day, though that was, of course, part of it. Those who love da Vinci suggest that he thought questions led to other questions, and that if he asked enough questions they might lead to other questions, until he arrived at an answer to a question he never considered before. Da Vinci’s was an ego-less approach to problem solving that most of us can’t do without attaching our questions to personal beliefs, conventional wisdoms, and other such biases. My guess is da Vinci kept asking himself questions to attempt to drain them of any personal convictions he might have on a subject. Then when he arrived at answers, he immediately went about trying to disprove them. He didn’t invent the step we now include in the scientific method, but he turned the practice into an artform in his own pursuits.

When Leonardo da Vinci approached something as simple as water flow, we can guess that by the time he seriously sat down to understand it, he had all of the conventional thoughts of the day running around in his head. He probably read as many books on it as were available to him at the time (if there were any), and he talked to any experts he could find whom he considered far more intelligent than he. At some point, he either thought they were all wrong on the subject, or he felt he needed to verify their answers for himself. Either way, Isaacson details some of the observations da Vinci made, and some of the experiments he conducted to understand it better. Da Vinci wasn’t the first to study water, of course, nor was he the last, but we have to believe that he was one of the few. We have to imagine that few have endured the hours, or an accumulation of months and probably years trying to understand it, because it comes equipped with one powerful deterrent: it’s boring. Even before the advent of radio, TV, the internet, and smartphones gave us all something to do to stave off boredom, studying water had to be pretty low on the list of things for anyone to do on otherwise boring Saturday afternoon. How much time did da Vinci sit outside watching water, how much time did he spend conducting experiments to understand the true nature of water? How much of his life did he devote to trying to arrive at an answer that no one would ever care about, even if he did publish his findings? Even if all he did was accurately portray the flow of water in one of his paintings, it probably only satisfied da Vinci and a small cadre of art enthusiasts who focus on the tiny minutiae that separates the talented from the brilliant. How many of his patrons would recognize such minute detail, and laud him for it? Was there anything more than a personal reward for the laborious study he put into making sure a couple of brushstrokes were accurately portraying what he discovered to be a truth about water? The only thing more boring than studying water to find the greater truths about it, as Isaacson’s book illustrates, is reading about it.

Perhaps the only interesting element of da Vinci’s study of water is why was he inspired to pursue it when many considered the topic so thoroughly explored? At what point do relatively uninformed people become so informed that they are confident enough to question the conventional information of their esteemed peers on a subject? We can only guess that he was intimidated by the experts’ intellect in his formative years, but he progressed beyond that. We all go through these progressions in varying ways. We all accept what our parents say as fact, but we begin to question them when at a certain age. Our parents are our primary authority figures, for much of our lives, and they’re our go-to for answers. When we find out they’re wrong on some things, we naturally assume they’re wrong about everything. We know our parents, and we know their vulnerabilities. Most experts’ vulnerabilities are not as available to us, so we cede authority of a subject to them on the subject to which they claim authority. Some of us don’t. Some of us, such as Leonardo da Vinci, don’t pursue knowledge to prove anyone wrong, but we find intimacy with the truth when we investigate a matter for ourselves.

The questions da Vinci had about water were probably just as numerous as the ones he had about achieving flight, nature, and the numerous other answers to such detailed questions that no one, in his time, had ever asked before. Thus, a number of his findings were so far ahead of their time that when we eventually discovered his journals, and we deciphered them in a mirror, because he wrote them backwards, we discovered advances he made that were centuries prior to the same ones made by renowned scientists. As Momento Artem writes in The Clocktower, “It’s believed that if [da Vinci] released [his journals] during his lifetime, they would not only have changed renaissance science and medicine but also the scientific and medical worlds we have today.”

How many people died as a result of a procedure called bloodletting? If da Vinci released his journals on the heart, and his subsequent theories on blood flow, during his lifetime, or we discovered them sooner, they might have disproven the theories behind bloodletting and spared the millions of patients who followed the useless and hopeless pain of the procedure.”

Knowledge can be a powerful thing. It can ingratiate people to us, in a “I can’t believe you know that” frame, but it can also turn people away “Mr. Smartypants here, thinks he knows everything.” Leading anatomists of his era probably would’ve done everything they could to discredit da Vinci for providing data that might prove them wrong, if he published these journals. The religious institutions of his era surely would’ve declared his views of the human body as a beautiful, self-sufficient machine blasphemous and heretical. How many political and medical industries would’ve been destroyed and presumably rebuilt, based on his findings? One thing we know about human nature, no matter the era, is that people don’t enjoy finding out they are wrong. Many of da Vinci’s tests, findings, and theories arrived at by scientific methods bore fruit, of course, but if he permitted publication of his findings, da Vinci probably would’ve been a pariah in his era. It’s possible he would’ve been exiled, excommunicated, or executed for publishing his findings, as they were the most popular methods those of his era had for dealing with those with whom they disagree, but the other method they had was various forms of book burning. Would da Vinci have been declared such a blasphemous heretic that the religious community, the medical community, and all of the politicians who supported them probably would’ve branded da Vinci’s work in such a way that we wouldn’t have any of his great paintings or his journals? How likely is it that popular opinion might brand da Vinci’s work in such a way that anything he did would be branded in such a light that they would’ve approached the owner of the work with torches to destroy it?

No matter how we characterize da Vinci, it’s obvious he considered himself a one man show. He didn’t accept an idea based on politics, religion, or what was widely accepted in the scientific community as a truth either. Nor was he married to his own ideas. As with most great scientists, he made a number of false assumptions that led to numerous mistakes. When he recognized those mistakes, his journals note his frustrations by saying things like, “impossible to know”. Those of us who love reading about the brilliant minds of history, and have read almost all of Isaacson’s books, know that even acclaimed geniuses make huge errors, and/or declare a subject “impossible to know”. It’s as if they’re saying, “If I can’t figure it out, it’s impossible to know.” Unlike most people, however, da Vinci didn’t let himself get in the way of him eventually finding an answer, or the truth. His notes detail an impatience with the project and the very human frustration of not being able to find the answer quickly, but they also inform us of a resolve that might have superseded most of his peers in eventually arriving at answers that still shock the world. It shocks us that he arrived at some unprecedented conclusions, because we consider his resources and the conventional wisdoms of his era. He didn’t care, to some degree, if his findings offended the politicians, the religious, or his friends. I write to some degree, because there were reasons why he never published the work, and there were reasons why he wrote it all backwards.

The knowledge I have on art, in general, and da Vinci in particular, barely scratches the level of novice. So, I assumed that my art enthusiast friend knew more about Leonardo da Vinci than I ever would. When you’re a novice with a particular obsession, you assume everyone knows more than you. Novices don’t know where they first heard the nuggets of information they share. We can’t remember where our fascination started. We read books, little nuggets on various websites, and we watched bios and documentaries, and we compiled so much over the years that much of Isaacson’s book was rehash. When I dropped these little nuggets on this art enthusiast, I expected her to nod and usher me forward with leading questions to information Isaacson unearthed that she didn’t know. Her amazement at what I considered elementary knowledge of da Vinci informed me that some of the times the relatively useless trivia we have swimming around our heads can be surprising bits of information to the unsuspecting.