Hyper-vigilance is not a switch an artist turns on to create. It’s less about what an artist does and more about who they are. If this is true, we could say that the final products of artists, their artistic creations, are less about some supernatural gift and more about a culmination of hyper-natural observations of the minutiae that others often miss that we call hyper-vigilance. Thus, in some cases, the final product of an artist’s vision is less about an artistic vision and more about using that product as a vehicle to reveal their findings. Did Leonardo da Vinci’s obsessions drive him to be an artist, or did he become so obsessed with the small details of life that he become an artist?

What goes on in the mind of an artist? That question has plagued us since Leonardo da Vinci, and before him. Those who don’t understand the complexities and gradations of artistic creation love to think about an “aha moment”, such as an apple falling on Isaac Newton’s head. Others think that brilliant artistic creation often requires one to mix the chemicals of their brain up with artificial enhancements, or that they ripped off the artists who preceded them. These theories combine some elements of truth with a measure of “There’s no way one man is that much more brilliant than I am” envy. As an aspiring artist, I can tell you that nothing informs the process more than failure, or trial and error. There are rarely “aha moments” that rip an artist out of a bathtub to lead them to type a passage half naked and dripping wet. What’s more common in my experience involves the search for an alternative, or a better way. Rather than intro a piece in the manner I’ve always done, maybe I should try introducing another way, maybe I should build to the conclusion a different way, and all of the gradual, almost imperceptible changes an artist makes along the road to their version of the “perfect” artistic creation.

To the untrained eye, The Mona Lisa is a painting of a woman. The Last Supper is nothing more than a depiction of the apostles having a meal with Jesus. We have some evidence of da Vinci’s process in his notebooks, but we don’t have his early artistic pieces. Due to the idea that they probably weren’t great, either da Vinci trashed them, or they’ve been lost to history in one way or another. These pieces would be interesting if, for no other reason, than to see the progress that led him to his masterpieces. Of the few da Vinci paintings that remain, we see a progression from his first paintings to The Mona Lisa. His paintings became more informed throughout his artistic career. This begs the chicken or the egg question, what came first Leonardo da Vinci’s artistic vision or the science behind the paintings? Put another way, did he pursue his innovative ways of attaining scientific knowledge to enhance his paintings, or did he use the paintings as a vehicle to display the knowledge he attained?

On that note, anytime I read a brilliant line I often wonder if the inspiration for the line dropped in the course of the author’s effort, or if the brilliant line was the whole reason for the book. Was the book an elongated attempt to verbally shade that brilliant line, in the manner da Vinci did his subjects, to make the brilliant line more prominent?

Whatever the case was, the few works of his we still have are vehicles for the innovative knowledge he attained of science, the mathematics of optics, architecture, chemistry, and the finite details of anatomy. Da Vinci might have started obsessively studying various elements, such as water flow, rock formations, and all of the other natural elements to better inform his art, but he became so obsessed with his initial findings that he pursued them for reasons beyond art. He pursued them for the sake of knowledge.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a book capture an artist’s artistic process as well as Walter Isaacson’s Leonard da Vinci biography has. The thesis of the book is that da Vinci’s artistic creations were not merely the work of a gifted artist, but of an obsessive genius honing in on scientific discoveries to inform the minutiae of his process. Some reviews argue that this bio focuses too much on the minutiae involved in da Vinci’s work, and there are paragraphs, pages, and in some cases entire chapters devoted to the minutiae involved in his process. In some places, I empathize with this charge that the book can be tedious, but after finishing the book, I don’t know how any future biographer on da Vinci could capture the essence of Leonardo da Vinci without the exhaustive detail about the man’s obsessive pursuit of detail. Focusing and obsessing on the finer details is who da Vinci was, and it is what separated him from all of the brilliant artists that preceded and followed him.

Some have alluded to the idea that da Vinci just happened to capture Lisa Gherardini, or Lisa del Giocondo, in the perfect smile for his famous painting The Mona Lisa. The inference is that da Vinci asked her to do a number of poses, and that his gift was merely in working with the woman to find that perfect pose and then capture it, in the manner a photographer might. Such theories, Isaacson illustrates, shortchange the greatest work of one of history’s greatest artists. It leaves out all of these intricate and tedious details da Vinci used to bring the otherwise one-dimensional painting to life.

Isaacson also discounts the idea that da Vinci’s finished products were the result of a divine gift, and I agree in the sense that suggesting his work was a result of a gift discounts the intense and laborious research da Vinci put into informing his works. There were other artists with similar gifts in da Vinci’s time, and there have been many more since, yet da Vinci’s work maintains a rarefied level of distinction in the art world.

As an example of Leonardo’s obsessiveness, he dissected cadavers to understand the musculature elements involved in producing a smile. Isaacson provides exhaustive details of Leonardo’s work, but writing a couple of paragraphs about such endeavors cannot properly capture how tedious this research must have been. Writing that da Vinci spent years exploring cadavers to discover all the ways the brain and spine work in conjunction to produce expression, for example, cannot capture the trials and errors da Vinci must have experienced before finding the subtle muscular formations inherent in the famous, ambiguous smile that captured the deliberate effect he was trying to achieve. (Isaacson’s description of all the variables that inform da Vinci’s process regarding The Mona Lisa’s ambiguous smile that historians suggest da Vinci used more than once, is the best paragraph in the book.) We can only guess that da Vinci spent most of his time researching for these artistic truths alone, and that even his most loyal assistants pleaded that he not put them on the insanely tedious lip detail.

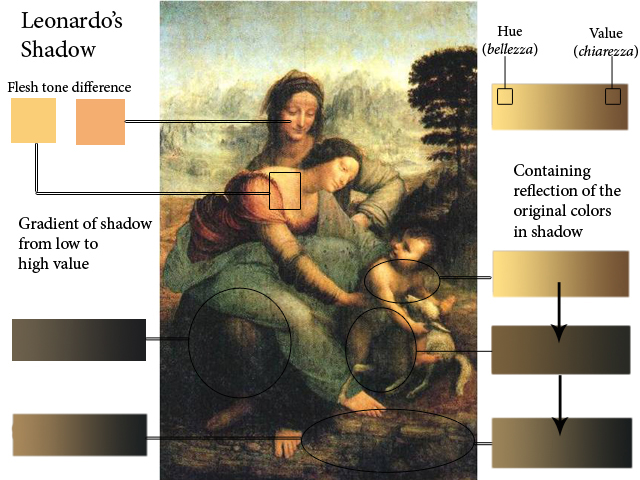

Isaacson also goes to great lengths to reveal Leonardo’s study of lights and shadows, in the sfumato technique, to provide the subjects of his paintings greater dimension and realistic and penetrating eyes. Da Vinci then spent years, sometimes decades, putting changes on his “incomplete projects”. Witnesses say that he could spend hours looking at an incomplete project only to add one little dab of paint.

The idea that da Vinci’s works were a product of supernatural gift also implies that all an artist has to do is apply that gift to whatever canvas stands before them and that they should do it as often as possible to pay homage to that gift until they achieve a satisfactory result. As Isaacson details, this doesn’t explain what separates da Vinci from other similarly gifted artists in history. The da Vinci works we admire to this day were but a showcase of his ability, his obsessive research on matters similarly gifted artists might consider inconsequential, and the application of that knowledge he attained from the research. This, I believe, suggests da Vinci’s final products were less about anything supernatural and more about an intense obsession to achieve something hyper-natural.

Why, for example, would one spend months, years, and decades studying the flow of water, and its connections to the flow of blood in the heart? The nature of da Vinci’s obsessive qualities belies the idea that he did it for the sole purpose of fetching a better price for his art. As Isaacson points out, da Vinci turned down more commissions than he accepted. This coupled with the idea that while he might have started an artistic creation on a commissioned basis, he often did not give the finished product to the one paying him for the finished product. As stated with some of his works, da Vinci hesitated to do this because he didn’t consider the piece finished, completed, or perfect. As anyone who experiences artistic impulses understands, the idea that an artistic piece has reached a point where it cannot be improved upon is often more difficult for the artist to achieve for the artist than starting one.

What little we know about da Vinci, suggests that he had the luxury of never having to worry about money. If that’s the case, some might suggest that achieving historical recognition drove him, but da Vinci had no problem achieving recognition in his lifetime, as most connoisseurs of art considered him one of the best painters of his era. We also know that da Vinci published little of what would’ve been revolutionary discoveries in his time, and he carried most of his artwork with him for most of his life, perfecting it, as opposed to selling it, or seeking more fame with it. Due in part to the luxuries afforded him, and the apparent early recognition of his talent, most cynical searches for his motivation do not apply. As Walter Isaacson’s biography of Leonard da Vinci implies, it’s difficult to find a motivation that drove the man to create the few works of his we now have other than the pure, passionate pursuit of artistic perfection.

After reading through all that informed da Vinci’s process, coupled with the appreciation we have for the finished product, I believe we can now officially replace the meme that uses the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album to describe an artist’s artistic peak with The Mona Lisa.