“You are what we call a processor,” my boss said in a one-on-one meeting. “You study the details of a question before you answer. It might take you more time to arrive at a conclusion, but once you do, you come up with some unique, creative thoughts. There’s nothing wrong with it. We just think differently, and when I say we,” Merri added to soften the blow, “I include myself as well, for I am a bit of a processor too. So, it takes one to know one.”

Merri added some personal anecdotes to illustrate her point, but the gist of her comment appeared to spring from the idea that she was a quality manager who knew I was struggling under the weight of a quick thinking co-worker that she considered a marvel. I may be speculating here, but I think Merri knew that the best way to get the most out of me was to sit me down and inform me that in my own way I was a quality employee too.

That woman just called me slow, I thought as she illustrated her point. She may have dressed it up with a bunch of pleasant, pretty adjectives, but the gist of her analysis is that I was a slow thinker. I tried to view the comment objectively, but the sociocultural barometers list a wide array of indicators of intelligence, but foremost among them are speed and quickness. She just informed me that I was the opposite of that, so I considered her analysis the opposite of a compliment.

That woman just called me slow, I thought as she illustrated her point. She may have dressed it up with a bunch of pleasant, pretty adjectives, but the gist of her analysis is that I was a slow thinker. I tried to view the comment objectively, but the sociocultural barometers list a wide array of indicators of intelligence, but foremost among them are speed and quickness. She just informed me that I was the opposite of that, so I considered her analysis the opposite of a compliment.

I tried to come up with some compelling evidence to defeat her analysis of me. Yet, every anecdote I came up with only proved her point, so I chose to focus on how unfair it was that those of us who analyze situations before us, to the point of over-analyzing, and at times obsessing over them, receive less recognition for the answers we find. We receive some praise, of course, when we develop a solution, but it pales in comparison to those who “Boom!” the room they own after with quick formulation of the facts that result in a quick answer. Even on those occasions when my superiors eventually deemed my solution a better one, I didn’t receive as much praise as the person who came up with a quick, quality answer in the moment.

I don’t know how long Merri spoke, or how long I debated my response internally, but I changed my planned response seven or eight times based on what she was saying. Two things dawned on me before Merri’s silence called for a response. The first was that any complaint I had about the reactions people have to deep, analytical responses as opposed to superficial, quick thoughts, were complaints I had regarding human nature, and the second thought I had was any response I gave her would be a well thought out, thoroughly vetted response that would only feed into her characterization. “And that’s exactly what I’m talking about,” was what I expected her to say to anything I thought up.

Putting those complaints about human nature aside for a moment, Merri’s characterization of my thinking pattern was spot on. It took me a while to appreciate the depth of her comment, and that, too, proves her point, but she didn’t really know me well enough to make such a characterization. I think it was a guess on her part that just happened to be more spot on than she’ll ever know.

Merri’s characterization eventually evolved my thinking about thinking, and it led me to know a little bit more about knowing it than I did before my one-on-one with her. Her comment also led to be a little more aware of how I operated. Before I sat down with her, I knew I thought different. I went through a variety of different methods to pound facts home in my head, but I never considered the totality of what she was saying before.

This was my fault for the most part, but I never met a person who thought about the thinking process in this manner before. They may have dropped general platitudes on thinking, with regard to visual, auditory, and kinesthetic learning styles, but no one ever sat me down and said, “You’re not a dumb guy, you just need to learn how you think.”

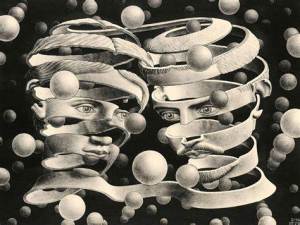

Merri’s commentary on my thinking process was an epiphany in this regard, for it led to a greater awareness about my sense of awareness, or what psychologists call my metacognition. The first level of knowledge occurs when we receive information, the second regards how we process it in a manner that reaches beyond memorization to application, and a third might be achieving a level of awareness for how we do all of the above.

When she opened my mind’s eye to the concept of processing speeds, I began to see commentary on it everywhere. I witnessed some characterize it as ‘deep thinking’. This might be true in a general sense, but the reader’s inclination might lead them to view this as a self-serving characterization. Slow processors, I thought, have endured so much abuse over the years that we might reconsider this re-characterization a subtle form of revenge against those who have called us slow. When a person informed me that I might be a deep thinker, I loved it so much that I wanted to repeat it, but I cringed every time I felt the urge, because I think we should leave such characterizations to others. There is an element of truth to it, however, and it arrives soon after a processor begins to believe he’s incompetent, slow, or dumb.

Most reflective processors are former dumb people. Intelligent people may disagree, but if most theories are autobiographical then we must factor my intelligence into the equation. My autobiographical theory goes something like this. I spent my schooling years trying to achieve the perception of a quick thinker, and I failed miserably. When the teacher asked a question, I would raise my hand. My answers were wrong so often that a fellow student said, “Why do you keep raising your hand? You’re always wrong.” I would also hear groans, ridicule, and embarrassment for other incorrect answers in other classes, until I was so intimidated that I decided not to answer questions anymore. In school, as in all other areas of life to follow, we know that rewards go to immediate, quick thinkers.

Before Merri provided my thought process a much-needed title, I assumed I didn’t know enough to know enough. I took this perspective into everyday situations. I didn’t just consider other, more knowledgeable perspectives to resolve my dilemmas I relied on them for answers. The cumulative effect of this approach led me to begin processing information more and more often, until I gathered enough information to achieve some level of knowledge on a given subject.

Before Merri provided my thought process a much-needed title, I assumed I didn’t know enough to know enough. I took this perspective into everyday situations. I didn’t just consider other, more knowledgeable perspectives to resolve my dilemmas I relied on them for answers. The cumulative effect of this approach led me to begin processing information more and more often, until I gathered enough information to achieve some level of knowledge on a given subject.

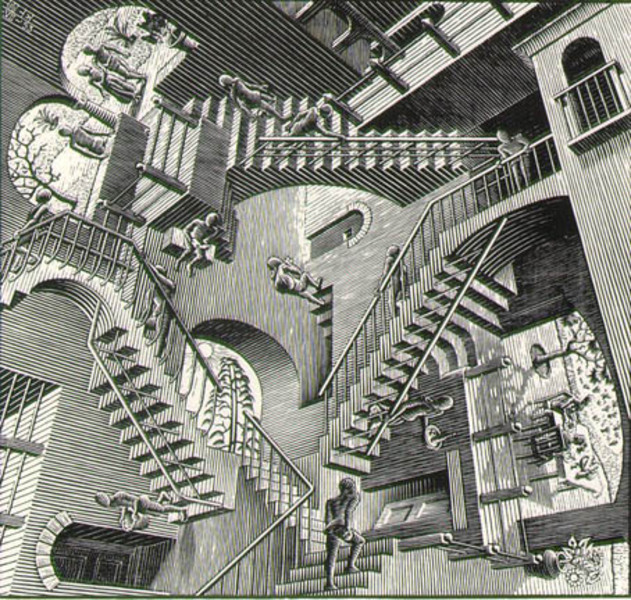

In my search to find intellectuals who could conceptualize this notion better, I discovered the ‘down the stairs’ concept. This concept is not revolutionary, but it does frame the idea well. The ‘down the stairs’ thinker attends a corporate meeting in which a corporate idea, or concept, is introduced. The supervisor will conclude that meeting by asking if anyone has any questions or input they would like to add. The quick thinkers, flood the room with thought-provoking, leading questions and concepts that the supervisor appreciates. The processor says nothing, because he can’t think of anything in the moment. The meeting ends, and he walks back to his desk (down the proverbial stairs), when an idea hits him. We write that specific timeline to stay true to the analogy, but our ideas unfortunately do not occur that quickly. We often have to chew on the concepts and problems introduced in the presentation for far too long sometimes, so long that the cliché ‘let me sleep on it’ definitely applies to our style of thinking.

The opposite occurs in boardrooms and classrooms throughout the country. Hands go up, an exchange of ideas occurs, and quick thinkers are rewarded in all the ways quick thinkers are rewarded. We would love to write, right here, in this space, that these ideas are not well thought out, impulsive, and short-sighted, but some of these ideas are pretty good. How do they come up with these ideas so fast? It can prove overwhelming and depressing. I heard some great ideas in what that guy had to say, this other guy had some nuggets nestled in his otherwise impulsive, short-sighted idea, and that other guy’s idea was worthless, but I wondered if I flipped it around and turned it inside out if there might be something worthwhile in there.

The meeting, just like every meeting, class, and group setting of any kind, depressed me, because I wasn’t the participant that I should’ve been. Once I got over all that, and I slowed everything down, I came up with my “down the stairs,” ideas over time so often that my long time manager, Merri, began to notice the pattern.

This dilemma might lead us to ask, if an idea is good enough, who cares when an idea hits as long as it hits? The processor who wants the perception of being quick cares. He wants others to marvel at his intellect in the moment. The depressing aspect of being a processor is that you rarely receive the “time and place” credit quick-witted types, like Ron and Bret, receive. “You came up with that idea? Not bad. Why didn’t you say anything in the meeting?”

“I didn’t think about it at the time,” we’d say if we knew what we were talking about when it comes to our way of thinking. If we were brutally honest with ourselves, we’d add, “I just don’t think as fast as Ron and Bret.” We don’t add that, because we know even if the boss loves our idea, she’s going to say something like, “Well, it’s a good idea regardless.” It’s that word regardless that just sticks in our craw. There shouldn’t be a regardless in that compliment. The compliment should be a standalone, but it’s human nature to reward hair trigger intellect. They might even implement our idea over Ron and Brett’s, and that’s some reward, but it sits on our mantle with a ‘regardless’ ribbon wrapped around it. And if they add a “Hey, you’re just as smart as Bret and Ron” pat on the back that’s just dripping with condescension, it feels like a consolation prize.

The inevitable question arises, “Why do you care so much about credit and rewards?” They also ask those questions based on Ronald Reagan’s quote, “There is no limit to the amount of good you can do if you don’t care who gets the credit.” These idealistic platitudes are from people accustomed to receiving credit for those of us toiling away in obscurity, we would love to know a world where we receive so much credit that we can humbly brush it aside.

Slow processors do receive some credit, but it pales in comparison to quick thinkers. Our mission is self-serving, of course, but we want the level of credit we’ve been denied for so long. The seeds of frustration and confusion are borne there, until someone, like Merri, comes along and clarifies the matter for us.

A college professor once praised a take-home, assigned essay I wrote on some required reading. She stated that the ideas I expressed in that essay were “unique and insightful” and she included a note about wanting me to participate more in in-class discussions, because she said she thought I could add something to add to them. My wrong answers in high school and the resultant teasing all but beat class participation out of me, but I tried to live up to her compliments the next class. That experience only reiterated why I shouldn’t be answering questions in class. I was so wrong so often that she gave me a confused and somewhat suspicious look. I didn’t see the suspicion in the moment, and I wouldn’t think about it again until we took the final, which involved an in-class essay on another book. That teacher watched me in a manner similar to a shop owner watching a suspected shoplifter. She thought I had someone else write that prior essay she loved. I received the same grade on that final, and many of the same compliments followed that grade, and this experience may have taught that teacher as much as Merri taught me about the different ways people think.

A college professor once praised a take-home, assigned essay I wrote on some required reading. She stated that the ideas I expressed in that essay were “unique and insightful” and she included a note about wanting me to participate more in in-class discussions, because she said she thought I could add something to add to them. My wrong answers in high school and the resultant teasing all but beat class participation out of me, but I tried to live up to her compliments the next class. That experience only reiterated why I shouldn’t be answering questions in class. I was so wrong so often that she gave me a confused and somewhat suspicious look. I didn’t see the suspicion in the moment, and I wouldn’t think about it again until we took the final, which involved an in-class essay on another book. That teacher watched me in a manner similar to a shop owner watching a suspected shoplifter. She thought I had someone else write that prior essay she loved. I received the same grade on that final, and many of the same compliments followed that grade, and this experience may have taught that teacher as much as Merri taught me about the different ways people think.

How many of us grow up thinking we’re dumb? How many brilliant minds grew up with a complex in that regard? What did they learn about themselves through life?

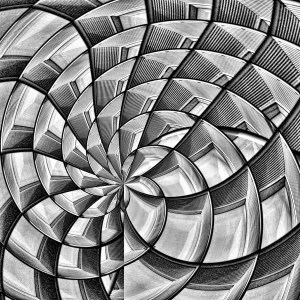

The theme of David McRaney’s You are Not so Smart was obviously that we are not as smart as we think we are. The various essays in that book describe why we do the things we do, and how various psychological mechanisms condition us to do the things we do. I loved that book so much that I’ve written probably thirty of my own articles on the theme. This particular article is entitled You are Not so Dumb for the reason that I think it’s the antithesis of that book, and its purpose is to provide some relief for those who are so confused and frustrated that they cannot think quicker. Some of us think in different ways and at different speeds. This could be why the art of writing attracts some more than others, for it allows us to sit in our vestibule and prove we were/are not as dumb as we thought we were/are in the classrooms and boardrooms where quick thinkers beat us to the rewards through quick answers. The reader who doesn’t know what we’re talking about here, might think that we’re attempting to right the wrong to prove something to you, and to be brutally honest, we are, but by writing this article, and everything else we’ve written, we’re also proving something else to ourselves.

The depression slow processors experience can be like a slow drum beat that beats them down over time, until it defeats them. If this antidote spares one person from the decades of frustration I experienced in this regard, I might consider this the best article I’ve ever written, but I would do so without ego, for I am merely passing another person’s observation along. If the reader identifies with the characterizations we’ve outlined here, I do have one note of caution: You may never rid yourself of this notion that you’re less intelligent than that firecracker over there in the corner, and the frustrating fact is he will always receive more rewards professionally, socially, and otherwise, but if you can come to grips with the manner in which you think, how you process information, and know it to the point of arriving at an answer without all of the frustration you experience when everyone else is shouting answers out, it’s possible that you might achieve some surprising results. We might never reach a point of bragging for I don’t know how anyone could dress up the idea of being a slow thinker, but attaining knowledge of self can go a long way to understanding how we operate, and it’s our job to take it and use it accordingly.