You want to get weird? I’m not talking about the weird music our aunts and uncles might chuckle at or say, “Hey, that’s kinda neat-o.” I’m talking about a strain so close to normal that they mi

ght be a little concerned about our mental health when they hear it. “If you think that’s quality music, then I’m probably going to have to edit my perception of you.” I’m talking about a definition of different carved out in a band called Mr. Bungle, then chiseled into with Fantômas, and ultimately destroyed and reconstructed in a project called Moonchild. If you don’t know who I’m talking about, let me introduce you to the outlandish innovations of a bizarre brainchild named Mike Patton.

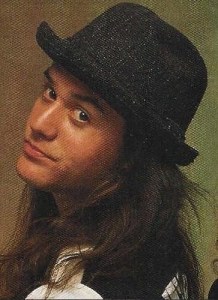

“Isn’t he a one-hit wonder?” a friend of mine asked, decades after Mike Patton became Mike Patton. “Isn’t he the “It’s it what is it?” guy?” I was so stunned that I couldn’t think up an appropriate term for cluelessness. Then, VH1 went ahead and confirmed his uninformed characterization, by listing the band Patton fronted, Faith No More as one of their one-hit wonders of the 80s. I knew most didn’t follow the career of Mike Patton as much as I had, but I was stunned to learn how even those with purported knowledge in the industry could dismiss him in such a manner. I had to adjust my idealistic vision of the world to reconcile it with the reality that if Billboard is your primary resource, Mike Patton and Faith No More were one-hit wonders. To those of us who live in the outer layer, seeking the sometimes freakishly different, “It’s it what is it?” or the single Epic, was only the beginning.

Mike Patton discovered he had a talent at a young age, he could mimic bird calls. He found that he could also perform some odd vocal exercises on a flexi disc that his parents gave him. The idea that he could do that probably didn’t separate him much from the four-to-five billion on the planet at the time, and I only include that note to suggest that Mike Patton probably didn’t even know how talented he was at the time either.

ght be a little concerned about our mental health when they hear it. “If you think that’s quality music, then I’m probably going to have to edit my perception of you.” I’m talking about a definition of different carved out in a band called Mr. Bungle, then chiseled into with Fantômas, and ultimately destroyed and reconstructed in a project called Moonchild. If you don’t know who I’m talking about, let me introduce you to the outlandish innovations of a bizarre brainchild named Mike Patton.

“Isn’t he a one-hit wonder?” a friend of mine asked, decades after Mike Patton became Mike Patton. “Isn’t he the “It’s it what is it?” guy?” I was so stunned that I couldn’t think up an appropriate term for cluelessness. Then, VH1 went ahead and confirmed his uninformed characterization, by listing the band Patton fronted, Faith No More as one of their one-hit wonders of the 80s. I knew most didn’t follow the career of Mike Patton as much as I had, but I was stunned to learn how even those with purported knowledge in the industry could dismiss him in such a manner. I had to adjust my idealistic vision of the world to reconcile it with the reality that if Billboard is your primary resource, Mike Patton and Faith No More were one-hit wonders. To those of us who live in the outer layer, seeking the sometimes freakishly different, “It’s it what is it?” or the single Epic, was only the beginning.

Mike Patton discovered he had a talent at a young age, he could mimic bird calls. He found that he could also perform some odd vocal exercises on a flexi disc that his parents gave him. The idea that he could do that probably didn’t separate him much from the four-to-five billion on the planet at the time, and I only include that note to suggest that Mike Patton probably didn’t even know how talented he was at the time either.

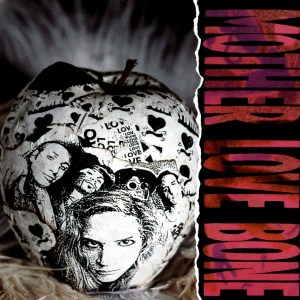

Yet, the young Mike Patton knew he loved music. He loved it so much that he and his buddies in school, including Trey Spruance and Trevor Dunn, decided to form a band they called Mr. Bungle. They were all around fifteen at the time, and anyone who listens to their early self-produced demos, Bowel of Chiley (1987) and The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny(1986) can hear how young and inexperienced they were. These demos were a chaotic blend of metal, funk, and juvenile humor. It’s so chaotic that it’s as difficult to categorize as it is to listen to, but suffice it to say whatever general definition we might have of traditional music, the music found on those demos is likely the opposite.

While devoting himself to Mr. Bungle, and studying English literature at Humboldt State University, Patton worked at a local record store, immersing himself in everything from punk to classical. He obviously kept himself busy during this period, and we can only guess that he was probably as surprised as anyone else when, in 1988, a man named Jim Martin invited Patton to audition for the role of lead singer in Martin’s band Faith No More, after seeing Patton perform in a local gig as the lead singer of Mr. Bungle. Patton won the job after displaying his raw energy and his vocal range for the band.

If this were one of those always disappointing biodocs, the moviemakers would depict Martin and the other members of Faith No More as being blown away by Patton’s audition, and they would say something like, “This is obviously the man to lead us into the 90s.” I understand that these movies are often constrained by formulas and time constraints, and they often take shortcuts just to get a point across. I was all prepared to dispel that movie trope by writing that while the members of the band, their management, and the execs thought his audition was great, they heard the demos, and they didn’t think his talent would translate to Faith No More’s furthered success. It turns out, they were so blown away by the talent he displayed in that audition that they did consider him the man to lead them into the 90s. After hearing Mr. Bungle’s early demos, firsthand, all I can say is that must’ve been one hell of an audition.

Yet, the young Mike Patton knew he loved music. He loved it so much that he and his buddies in school, including Trey Spruance and Trevor Dunn, decided to form a band they called Mr. Bungle. They were all around fifteen at the time, and anyone who listens to their early self-produced demos, Bowel of Chiley (1987) and The Raging Wrath of the Easter Bunny(1986) can hear how young and inexperienced they were. These demos were a chaotic blend of metal, funk, and juvenile humor. It’s so chaotic that it’s as difficult to categorize as it is to listen to, but suffice it to say whatever general definition we might have of traditional music, the music found on those demos is likely the opposite.

While devoting himself to Mr. Bungle, and studying English literature at Humboldt State University, Patton worked at a local record store, immersing himself in everything from punk to classical. He obviously kept himself busy during this period, and we can only guess that he was probably as surprised as anyone else when, in 1988, a man named Jim Martin invited Patton to audition for the role of lead singer in Martin’s band Faith No More, after seeing Patton perform in a local gig as the lead singer of Mr. Bungle. Patton won the job after displaying his raw energy and his vocal range for the band.

If this were one of those always disappointing biodocs, the moviemakers would depict Martin and the other members of Faith No More as being blown away by Patton’s audition, and they would say something like, “This is obviously the man to lead us into the 90s.” I understand that these movies are often constrained by formulas and time constraints, and they often take shortcuts just to get a point across. I was all prepared to dispel that movie trope by writing that while the members of the band, their management, and the execs thought his audition was great, they heard the demos, and they didn’t think his talent would translate to Faith No More’s furthered success. It turns out, they were so blown away by the talent he displayed in that audition that they did consider him the man to lead them into the 90s. After hearing Mr. Bungle’s early demos, firsthand, all I can say is that must’ve been one hell of an audition.

This isn’t to suggest that Mike Patton didn’t devote himself to Faith No More, as he devoted an overwhelming amount of his time and energy to the band during their recording and touring of The Real Thing and Angel Dust (1992). He wrote the lyrics and melodies for both albums, toured extensively (over 200 shows for The Real Thing alone), and handled media duties. Mr. Bungle, meanwhile, was more of a side project during this period. Their self-titled debut (1991) was recorded in gaps between Faith No More’s schedule, with Patton contributing vocals, lyrics, and some production alongside bandmates Trey Spruance and Trevor Dunn.

This isn’t to suggest that Mike Patton didn’t devote himself to Faith No More, as he devoted an overwhelming amount of his time and energy to the band during their recording and touring of The Real Thing and Angel Dust (1992). He wrote the lyrics and melodies for both albums, toured extensively (over 200 shows for The Real Thing alone), and handled media duties. Mr. Bungle, meanwhile, was more of a side project during this period. Their self-titled debut (1991) was recorded in gaps between Faith No More’s schedule, with Patton contributing vocals, lyrics, and some production alongside bandmates Trey Spruance and Trevor Dunn.

In 1995, Mike Patton basically proved that a man could toggle between two bands and produce two great albums for each outfit. He played a pivotal role in both Faith No More’s King for a Day and Mr. Bungle’s Disco Volante. Patton wasn’t the first to play in two bands at once, by any means, but it wasn’t commonly done in this era. He stated that his daily routine consisted of recording King for a Day at Bearsville Studios, during the day, then driving down to record Disco Volante late into the night and repeating the same process the next day. “It was insane,” he told the Alternative Press in a 1996 interview. He admitted he barely slept while juggling both bands’ demands.

Patton never claimed to be a trailblazer in this regard, but he’s acknowledged the strain. In a 2001 Kerrang! interview, he called 1995 “a blur,” saying Mr. Bungle was his “heart” while Faith No More paid the bills. If you haven’t heard him interviewed, this is Mike Patton. He is a humble man who often downplays moments the rest of us consider groundbreaking. King for a Day was another great FNM album, not as good as Angel Dust, but better than The Real Thing, in my humble estimation. Disco Volante was, and is, an incredible album that any serious artist would consider a career achievement, better than the self-titled disc but not as great as California. Most Bungle fans disagree on the latter.

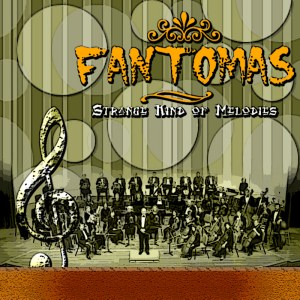

After spreading himself so thin in 1995, Patton went and got bored after Faith No More’s 1998 breakup, which the band “officially” stated was due to the fact that Faith No More had run its course creatively. Anyone who thinks that Patton would devote himself entirely to Mr. Bungle at this point just isn’t following along. He gets so bored that he ventures out and creates other artistic enterprises that take that definition of weird out to “Here, there be Dragons” locations on the map. He takes it to the ‘if you think Faith No More was outlandish in places, you should check out Mr. Bungle, and if you think Mr. Bungle stretches the boundaries of genre, you should check out a band he created called Fantômas.’ Fantômas became Patton’s new passion project while devoting an overwhelming amount of his time to what I consider the Mr. Bungle masterpiece 1999’s California.

In 1995, Mike Patton basically proved that a man could toggle between two bands and produce two great albums for each outfit. He played a pivotal role in both Faith No More’s King for a Day and Mr. Bungle’s Disco Volante. Patton wasn’t the first to play in two bands at once, by any means, but it wasn’t commonly done in this era. He stated that his daily routine consisted of recording King for a Day at Bearsville Studios, during the day, then driving down to record Disco Volante late into the night and repeating the same process the next day. “It was insane,” he told the Alternative Press in a 1996 interview. He admitted he barely slept while juggling both bands’ demands.

Patton never claimed to be a trailblazer in this regard, but he’s acknowledged the strain. In a 2001 Kerrang! interview, he called 1995 “a blur,” saying Mr. Bungle was his “heart” while Faith No More paid the bills. If you haven’t heard him interviewed, this is Mike Patton. He is a humble man who often downplays moments the rest of us consider groundbreaking. King for a Day was another great FNM album, not as good as Angel Dust, but better than The Real Thing, in my humble estimation. Disco Volante was, and is, an incredible album that any serious artist would consider a career achievement, better than the self-titled disc but not as great as California. Most Bungle fans disagree on the latter.

After spreading himself so thin in 1995, Patton went and got bored after Faith No More’s 1998 breakup, which the band “officially” stated was due to the fact that Faith No More had run its course creatively. Anyone who thinks that Patton would devote himself entirely to Mr. Bungle at this point just isn’t following along. He gets so bored that he ventures out and creates other artistic enterprises that take that definition of weird out to “Here, there be Dragons” locations on the map. He takes it to the ‘if you think Faith No More was outlandish in places, you should check out Mr. Bungle, and if you think Mr. Bungle stretches the boundaries of genre, you should check out a band he created called Fantômas.’ Fantômas became Patton’s new passion project while devoting an overwhelming amount of his time to what I consider the Mr. Bungle masterpiece 1999’s California.

We write all of this, and we don’t even get to Patton’s role as the lead vocalist in the five albums of Tomahawk, and then there’s his varying roles in the bands Peeping Tom, Dead Cross, Lovage, and the killer role he played in one of The Dillinger Escape Plan’s albums. He has two proper solo albums, two works with Kaada, various film scores, and over 60 collaborative efforts, various ensembles, and guest appearances on other artists’ albums, including John Zorn and Björk.

The overall brilliant catalog this “one-hit wonder” has amassed can be so overwhelming to the uninitiated that they may not even know where to start. 1989’s The Real Thing might, in fact, be the place to start, but I am so far past that starting point that I can’t even see it any more. That’s the problem with true fans of artists, they’ve listened to the artist for so long that they don’t know where to tell you where to start.

We write all of this, and we don’t even get to Patton’s role as the lead vocalist in the five albums of Tomahawk, and then there’s his varying roles in the bands Peeping Tom, Dead Cross, Lovage, and the killer role he played in one of The Dillinger Escape Plan’s albums. He has two proper solo albums, two works with Kaada, various film scores, and over 60 collaborative efforts, various ensembles, and guest appearances on other artists’ albums, including John Zorn and Björk.

The overall brilliant catalog this “one-hit wonder” has amassed can be so overwhelming to the uninitiated that they may not even know where to start. 1989’s The Real Thing might, in fact, be the place to start, but I am so far past that starting point that I can’t even see it any more. That’s the problem with true fans of artists, they’ve listened to the artist for so long that they don’t know where to tell you where to start.

Those who like Mike Patton, but don’t have an unusual, almost concerning adoration of him, tell me that Faith No More’s Angel Dust is probably the best starting point, as they say it’s probably the best, most mainstream album he took part in. If that’s the case, I would add Mr. Bungle’s California, Tomahawk Mit Gas, and Patton’s work with the X-Ecutioners as the second class of the Mike Patton beginner’s course. If you make it past that point, and you might not, I would submit Tomahawk’s Anonymous, Fantômas’s Suspended Animation, and Disco Volante as great second-level albums. A trend in Patton’s music I’ve noted, is the 2nd album trend. The first albums are great, but they seem to set a template from which to explore the dynamic further, and Patton and his various crews seem to peak with the ideas germinating around in their heads concerning what more can be done with this band. He helps build on the base idea of that first album, and they usually create something of a creative peak with those second albums. Don’t get me wrong, I love the third albums, as in King for a Day, Suspended Animation and Anonymous, and as I wrote I think California is better than Disco Volante, but the second album peak seems to be a standard for most of Patton’s ventures. (Most true Bungle fans would say Disco Volante is superior to California.)

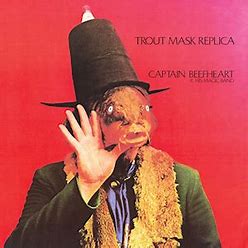

I imagine those with some authority in the conventional music world might begrudgingly admit that they once considered Mike Patton one of the most talented singers in rock music. They probably all acknowledged that he possessed one of the most versatile and dynamic voices in modern music, characterized by an extraordinary vocal range, stylistic adaptability, and emotive depth. His voice spans six octaves, reportedly from E1 to E7, though some sources conservatively estimate around five octaves (approximately C2 to C7). This range allows him to seamlessly shift from guttural growls and primal screams to operatic falsettos and silky crooning, often within a single song. The experts who admitted all that might also add, “At some point, it didn’t matter how talented he was, because he wasted that incredible voice on music so abrasive that he basically alienated so many of us. In 1995, we all loved the underappreciated King for a Day, but when he hit us with Disco Volante, we shook our heads trying to figure out what he was doing. Most of us dismissed the initial Bungle album a one-off side project, then he doubled down with an even weirder album, and he topped it all off with an album we considered career suicide with the vocal experiments on Adult Themes for Voice (1996). That led us to dismiss him, because we realized he had no interest in becoming a marketable talent.”

Those who like Mike Patton, but don’t have an unusual, almost concerning adoration of him, tell me that Faith No More’s Angel Dust is probably the best starting point, as they say it’s probably the best, most mainstream album he took part in. If that’s the case, I would add Mr. Bungle’s California, Tomahawk Mit Gas, and Patton’s work with the X-Ecutioners as the second class of the Mike Patton beginner’s course. If you make it past that point, and you might not, I would submit Tomahawk’s Anonymous, Fantômas’s Suspended Animation, and Disco Volante as great second-level albums. A trend in Patton’s music I’ve noted, is the 2nd album trend. The first albums are great, but they seem to set a template from which to explore the dynamic further, and Patton and his various crews seem to peak with the ideas germinating around in their heads concerning what more can be done with this band. He helps build on the base idea of that first album, and they usually create something of a creative peak with those second albums. Don’t get me wrong, I love the third albums, as in King for a Day, Suspended Animation and Anonymous, and as I wrote I think California is better than Disco Volante, but the second album peak seems to be a standard for most of Patton’s ventures. (Most true Bungle fans would say Disco Volante is superior to California.)

I imagine those with some authority in the conventional music world might begrudgingly admit that they once considered Mike Patton one of the most talented singers in rock music. They probably all acknowledged that he possessed one of the most versatile and dynamic voices in modern music, characterized by an extraordinary vocal range, stylistic adaptability, and emotive depth. His voice spans six octaves, reportedly from E1 to E7, though some sources conservatively estimate around five octaves (approximately C2 to C7). This range allows him to seamlessly shift from guttural growls and primal screams to operatic falsettos and silky crooning, often within a single song. The experts who admitted all that might also add, “At some point, it didn’t matter how talented he was, because he wasted that incredible voice on music so abrasive that he basically alienated so many of us. In 1995, we all loved the underappreciated King for a Day, but when he hit us with Disco Volante, we shook our heads trying to figure out what he was doing. Most of us dismissed the initial Bungle album a one-off side project, then he doubled down with an even weirder album, and he topped it all off with an album we considered career suicide with the vocal experiments on Adult Themes for Voice (1996). That led us to dismiss him, because we realized he had no interest in becoming a marketable talent.”

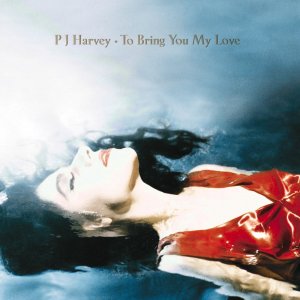

If you’ve read the writings of mainstream rock critics for as long as I have, you know that they have a difficult time understanding why someone would pick up a pencil and musical instrument and not try to do everything they could to sound like Springsteen, Dylan, or Joey Ramone. They don’t understand why someone would use vocal effects, as opposed to writing meaningful and important social commentary to help us reshape our world. We could excuse this with the idea that musical tastes are relative, but their blanket dismissal of anything different led me to start reading periodicals like Alternative Press and Decibel, who recognized what artists like Patton were trying to do. They praised Patton for his risk-taking, and they hailed his fearless innovation. As for the “marketable talent” comments we’ve heard, some fans and critics note that while he abandoned whatever mainstream potential awaited him, Mike Patton did develop a substantial cult following with each progression into the weird, strange, and just plain different.

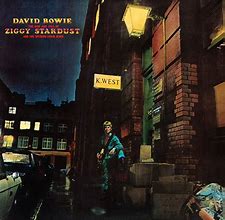

The next question any gifted artist must ask themselves soon after they discover they have a talent for something is what do I do with this? Patton, and Faith No More, could’ve followed up 1989’s The Real Thing with some version of The Real Thing Part Deux, and they could’ve gone onto develop a template, or a formula, in the ZZ Top, AC/DC vein. The mainstream music critics often eat up commodification of a brand as a cash grab. Mike Patton, and all of the musicians he chose to surround himself with in his numerous ventures, could’ve made a whole lot of money, enjoyed all the trappings of fame as rock stars. We can saw all we want about artistic integrity and all that, but it can’t be easy to turn away from the prospect of making truckloads of money. Contrary to what detractors say, money and fame can bring a us whole lot of happiness … if we love what we’re doing. If Mike Patton, and all of the musicians he chose to surround himself with in his numerous ventures, followed the formula of “building trust” with listeners, they would’ve been so bored and unsatisfied artistically. Patton obviously chose to use whatever gifts and talent he had to confound us and obliterate our boundaries in his pursuit of his version of artistic purity, and he chose projects and players who shared his philosophy. If the young Patton had a career path, or a place he “wanted to be in twenty years,” he obviously grew so bored with the “current” direction of his career so many times that he needed to do something decidedly different and out of his comfort zone so often that I don’t think he has any comfort zones left to destroy.

If you’ve read the writings of mainstream rock critics for as long as I have, you know that they have a difficult time understanding why someone would pick up a pencil and musical instrument and not try to do everything they could to sound like Springsteen, Dylan, or Joey Ramone. They don’t understand why someone would use vocal effects, as opposed to writing meaningful and important social commentary to help us reshape our world. We could excuse this with the idea that musical tastes are relative, but their blanket dismissal of anything different led me to start reading periodicals like Alternative Press and Decibel, who recognized what artists like Patton were trying to do. They praised Patton for his risk-taking, and they hailed his fearless innovation. As for the “marketable talent” comments we’ve heard, some fans and critics note that while he abandoned whatever mainstream potential awaited him, Mike Patton did develop a substantial cult following with each progression into the weird, strange, and just plain different.

The next question any gifted artist must ask themselves soon after they discover they have a talent for something is what do I do with this? Patton, and Faith No More, could’ve followed up 1989’s The Real Thing with some version of The Real Thing Part Deux, and they could’ve gone onto develop a template, or a formula, in the ZZ Top, AC/DC vein. The mainstream music critics often eat up commodification of a brand as a cash grab. Mike Patton, and all of the musicians he chose to surround himself with in his numerous ventures, could’ve made a whole lot of money, enjoyed all the trappings of fame as rock stars. We can saw all we want about artistic integrity and all that, but it can’t be easy to turn away from the prospect of making truckloads of money. Contrary to what detractors say, money and fame can bring a us whole lot of happiness … if we love what we’re doing. If Mike Patton, and all of the musicians he chose to surround himself with in his numerous ventures, followed the formula of “building trust” with listeners, they would’ve been so bored and unsatisfied artistically. Patton obviously chose to use whatever gifts and talent he had to confound us and obliterate our boundaries in his pursuit of his version of artistic purity, and he chose projects and players who shared his philosophy. If the young Patton had a career path, or a place he “wanted to be in twenty years,” he obviously grew so bored with the “current” direction of his career so many times that he needed to do something decidedly different and out of his comfort zone so often that I don’t think he has any comfort zones left to destroy.