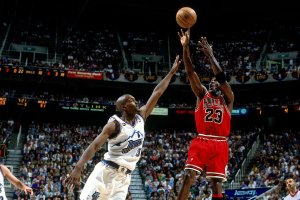

“If you think Michael Jordan is the greatest NBA player of all time, by far, you’re probably between the ages of 40-60,” blared one reddit commenter.

Some call it recency bias, but seeing as how Jordan took his Bulls’ jersey off for the final time 25 years ago, we could say that the recency bias exists in the pro-Kobe, pro-LeBron arguments. I’d call the pro-Jordan argument a generational bias. The generational bias suggests that everything that happened before and after my prime is not as great as it was during this relative window. With all these biases rolling around in everyone’s, it’s almost impossible to arrive at a final objective answer.

Some might also argue that the most instrumental bias in such arguments is the emotional bias. Those of the 40-60 demographic cheered harder for and against Jordan than later generations did Kobe and LeBron. That’s an almost impossible argument to debate, of course, as it’s all relative, but we do have statistics to argue and counter. That’s still impossible to argue, as Mark Twain once said, “There’s lies, damned lies and statistics.” It’s true, both teams can argue their statistics in the Jordan v LeBron argument, but there are stats and there are advanced metrics. Before we get into that argument, however, we must discount longevity, games started and played, and minutes, as LeBron entered the NBA straight out of high school, and Jordan played three years in college. Longevity and games played are valuable stats in our determination, but LeBron never retired, and Jordan did three times. LeBron obviously wins all of these categories.

Some might also argue that the most instrumental bias in such arguments is the emotional bias. Those of the 40-60 demographic cheered harder for and against Jordan than later generations did Kobe and LeBron. That’s an almost impossible argument to debate, of course, as it’s all relative, but we do have statistics to argue and counter. That’s still impossible to argue, as Mark Twain once said, “There’s lies, damned lies and statistics.” It’s true, both teams can argue their statistics in the Jordan v LeBron argument, but there are stats and there are advanced metrics. Before we get into that argument, however, we must discount longevity, games started and played, and minutes, as LeBron entered the NBA straight out of high school, and Jordan played three years in college. Longevity and games played are valuable stats in our determination, but LeBron never retired, and Jordan did three times. LeBron obviously wins all of these categories.

The advanced stats dig deep into actual games played, and they include value over replacement statistics, player efficiency rating, and fifteen other advanced statistics of the players’ respective careers that favor Michael Jordan 9-6, by category, in the regular season and LeBron James wins these metrics 9-8 in the postseason metrics. LeBron beats Jordan by a substantial number in win share, or the total number of wins contributed by a player, in both regular season and playoffs, which is surprising, but Jordan barely beats him in a majority of the regular season categories. It’s also surprising to see that the deep metrics in the postseason favor LeBron, as I would’ve guessed that would’ve been flipped. Big Game Mike, to my mind, took his game up to stratospheric, untouchable levels in the postseason. LeBron was better. If postseason is far more important than regular season stats, and an overwhelming number of people agree this is the case, LeBron actually has a slight advantage in most cases against Jordan.

Another publication used a more comprehensive approach, regular season and postseason combined, with advanced stats compiled by various publication. Their categorical verdict: dead even.

In the Clutch

Whenever Kobe or LeBron missed, and misses, a clutch playoff shot, some of us hit that “He’s not Jordan!” button. We don’t even consider that a bias at this point. It happened. We don’t remember Jordan ever missing a clutch playoff shot, but we do remember the many misses by Kobe and LeBron. The Bleacher Report developed a very simple formula for a definition of clutch shots in the playoffs. “Playoff games only (no regular season), go ahead or game-tying shot attempts (free throws, turnovers, and the like were ignored, [and the shot attempt had to occur in the]) final 24 seconds or he fourth quarter or overtime.” Within the constraints of this definition of playoff clutch shots, Jordan, they found, was 9-18 in clutch, playoff attempts, for “an astounding” 50% clip. LeBron is 7-16 for a 43.8% rate. (Not Jordan, but it was a lot closer than some of us remember.) Kobe was 7-25 for a 28% (or 5-17 for a 29.4% in the chart they provided).

Whenever Kobe or LeBron missed, and misses, a clutch playoff shot, some of us hit that “He’s not Jordan!” button. We don’t even consider that a bias at this point. It happened. We don’t remember Jordan ever missing a clutch playoff shot, but we do remember the many misses by Kobe and LeBron. The Bleacher Report developed a very simple formula for a definition of clutch shots in the playoffs. “Playoff games only (no regular season), go ahead or game-tying shot attempts (free throws, turnovers, and the like were ignored, [and the shot attempt had to occur in the]) final 24 seconds or he fourth quarter or overtime.” Within the constraints of this definition of playoff clutch shots, Jordan, they found, was 9-18 in clutch, playoff attempts, for “an astounding” 50% clip. LeBron is 7-16 for a 43.8% rate. (Not Jordan, but it was a lot closer than some of us remember.) Kobe was 7-25 for a 28% (or 5-17 for a 29.4% in the chart they provided).

| Player | Makes | Attempts | FG% |

| Michael Jordan | 9 | 18 | 50 |

| LeBron James | 7 | 16 | 43.8 |

| Kevin Durant | 5 | 12 | 41.7 |

| Dirk Nowitzki | 5 | 12 | 41.7 |

| Kobe Bryant | 5 | 17 | 29.4 |

Microsoft’s Co-Pilot program lists the following clutch field goal percentages for NBA greats in the playoffs. Jordan 45%, Kobe 41%, Bird 40%, Lillard 42%, Wade 42%, and Horry, LeBron, Magic were all at 40%. So, although, Jordan leads the pack, it’s not by as much as the 40-60 aged demographic remembers.

One contrarian argument I read online, states that the disparity between the elite talent and average player the 90s and the 2020s, favors the 2020s. They argue that the worst teams of the 90s were far worse than the worst teams of the 2020s. They argue that “There’s no question that the average player is more skilled today than in the 90’s.” They also write that The Chicago Bulls were able to achieve total dominance of the regular season thanks to expansion and a difference in defense rules. Another decent argument I’ve heard is that no one in the NBA, prior to Mike, had the marketing and promotion packages that he would receive.

In terms of marketing alone, I won’t even hear arguments about Bill Russell, Wilt, Kareem, or Dr. J. The only NBA marketing argument that comes close to that which Jordan received was Bird v Magic. If Bird v Magic saved the NBA, on a national level, however, Michael Jordan took it to the worldwide stage. Larry Bird was allergic to the press, and he only gave interviews begrudgingly, so that leaves the media-friendly smile and laughter of Magic Johnson. He was a hero to many, but his media attention paled in comparison to the worldwide, superstar treatment afforded Jordan. Kobe and LeBron later had a taste of it, of course, as they were the best players of their era, but they could never escape the cloud of “the chosen one”. The implicit statement is that Kobe and LeBron may have been as good, or better, than Jordan, but the 40-60 demo wouldn’t allow anyone to flirt with that notion. As a person who doesn’t follow the intricacies of the league, I must concede to the argument that part of Jordan’s impenetrable image as the GOAT revolves around how much the media adored him. The only marketing push that could come close to Michael Jordan was that of the “King of pop” Michael Jackson.

The Competition

To get to the core of this particular argument, we must dismiss the regular season records and the stats they achieved against average players. Even playoff teams have average, role players in every lineup, but if we were to stack the elite teams of each era against each other, let’s go seven deep on the various rosters, how would the late-80s, 90s Bulls, Pistons, Knicks, Jazz, Rockets, Sonics, do against the 2000s Spurs, the Shaq, Kobe Lakers, or the 2010s Warriors, Heat, Celtics and Lakers?

If we could somehow move the Jordans’ Bulls forward a decade or three, how do they fare against the elite teams of latter decades? First question, whose rules do they play under? Does Jordan operate better or worse in the wide-open rules of latter decades, or did the Warriors play an almost indefensible offense at their peak? On the flips side, if we could move the elite modern teams back, under the rules of yesteryear and Detroit’s “Jordan Rules” become “Kobe Rules” or “LeBron Rules”, do they overcome them in the manner Jordan eventually did? Would Tim Duncan, Ginobili, and Parker survive against Pat Riley’s brutal lane enforcement rules carried out by Charles Oakley, Anthony Mason and Xavier McDaniels? Do Jordan and the Bulls 4-2 Shaq and Kobe in championship series? If Jordan and LeBron play in the same era, does Jordan kill LeBron’s legacy the way he did so many others? As with just about every sport, it’s almost impossible to compare eras. The game changes, evolves, and adapts with rule changes. The brutal nature of the game in which no one was allowed a layup, became a wide-open, almost 3-point dependent game.

If we could somehow move the Jordans’ Bulls forward a decade or three, how do they fare against the elite teams of latter decades? First question, whose rules do they play under? Does Jordan operate better or worse in the wide-open rules of latter decades, or did the Warriors play an almost indefensible offense at their peak? On the flips side, if we could move the elite modern teams back, under the rules of yesteryear and Detroit’s “Jordan Rules” become “Kobe Rules” or “LeBron Rules”, do they overcome them in the manner Jordan eventually did? Would Tim Duncan, Ginobili, and Parker survive against Pat Riley’s brutal lane enforcement rules carried out by Charles Oakley, Anthony Mason and Xavier McDaniels? Do Jordan and the Bulls 4-2 Shaq and Kobe in championship series? If Jordan and LeBron play in the same era, does Jordan kill LeBron’s legacy the way he did so many others? As with just about every sport, it’s almost impossible to compare eras. The game changes, evolves, and adapts with rule changes. The brutal nature of the game in which no one was allowed a layup, became a wide-open, almost 3-point dependent game.

Focusing on the elite level alone, one reddit writer submits that: “There’s no evidence to support [the idea] that the [elite] players from the 90s are any better or worse than the [elite] players of today. In 632 games, Jordan never lost three games in a row, went 27-1 in playoff series [during that span], won three consecutive championships twice, 10 scoring titles, nine 1st-team all-defense awards. Led the league in steals 3 times, was the first player to ever record 200 steals and 100 blocks in one season and he did it twice [This stat, some would argue is timeless]. Won 14 MVPs (6 Finals, 5 regular seasons, 3 All Star game) plus 2 dunk contest championships. [He] was outscored once in 37 playoff series (in 1985 Terry Cummings outscored MJ by 1 point in the first-round series, 118-117), and [he] is 1st all-time in the number of times a player averaged 40 or more points in a playoff series. He did it 5 times and there’s a 4-way tie for 2nd place who have all done it [once]. [Jordan] also has outscored 982 out of 983 total opponents in career head2head match ups. (Alan Iverson being the only player ever by avg 27.1ppg in 7 games vs MJ who avg 24.4ppg). And this was all in 12 full regular seasons and 13 playoff appearances (15 active seasons). It’s basketballs greatest resume by a mile and those who weren’t there to see it do not want to believe it so, that’s why the 90s era gets no respect.”

The reddit user ends with a compelling argument. Most of the argument centers on the idea that we, the 40-60 demo, suffer from a number of biases, but the same could be said of those in the generation where Michael Jordan officially became a grandfather. If all you know of Michael Jordan are the YouTube videos, the “If I could be like Mike” commercials, the idea that Jordan was the GOAT might sound like “The Three Stooges were the greatest comedians of all time” or “The Andy Griffith Show was a greater sitcom than Seinfeld” arguments did to us. Unlike Curly or Barney Fife, most of Jordan’s exploits occurred between the highlights, on nights when it seemed like he couldn’t seem to miss midrange shots that only counted for two points. These weren’t the dramatic shots that we see on YouTube, but they don’t show what those in the 40-60 demo know.

The 90s Knicks

The best team the Bulls beat during this era would have to be the New York Knicks. Those Knicks 90s rosters may have been the best assemblage of NBA talent to never win an NBA Championship Ring. During Patrick Ewing’s run with the Knicks, they had John Starks, Charles Oakley, Anthony Mason, Xavier McDaniel, Greg Anthony, Gerald Wilkins, Derek Harper, Doc Rivers, Charles Smith, Mo Cheeks, Bill Cartwright, Bernard King, Hubert Davis, and the later rosters included Larry Johnson, Allan Houston, Marcus Camby, Anthony Bowie, and Latrell Sprewell, and they never won a ring.

The best team the Bulls beat during this era would have to be the New York Knicks. Those Knicks 90s rosters may have been the best assemblage of NBA talent to never win an NBA Championship Ring. During Patrick Ewing’s run with the Knicks, they had John Starks, Charles Oakley, Anthony Mason, Xavier McDaniel, Greg Anthony, Gerald Wilkins, Derek Harper, Doc Rivers, Charles Smith, Mo Cheeks, Bill Cartwright, Bernard King, Hubert Davis, and the later rosters included Larry Johnson, Allan Houston, Marcus Camby, Anthony Bowie, and Latrell Sprewell, and they never won a ring.

Jordan and the Knicks faced each other five times, in this era of their respective primes, and Jordan and the Bulls went 5-0 in those matchups. If the reader doesn’t consider that record eye-popping, go read Blood in the Garden to get a grasp on how talented those Knicks’ teams were.

Jordan retired (the first time) to play baseball? and Ewing and the Knicks lost to Hakeem Olajuwon’s Rockets then Reggie Miller’s Pacers. Jordan retires again, and the Knicks lose to Tim Duncan, David Robinson, and the Spurs. I still cannot believe Patrick Ewing, and his Knicks’ teams never won a ring.

The Late 80’s Early 90’s Pistons

The late 80s/early 90s Pistons’ run was not near as lengthy as the Knicks’, but they packed a whole lot of winning in that shorter time frame. Some rightly blame the talent around Jordan, but the Pistons beat Jordan and the Bulls in three straight playoff series from 1987-1990.

We can all admit to some type of bias in these never-ending arguments, but those of us in the 40-60 demographic will never be able to get passed “The Run”. When Jordan and the Bulls finally found a way to beat the Pistons, no team could stop them. They won six championships in a row (not counting the retirement years), and no one, outside the 60s Celtics, have been able to match such a run. Those of us in this demo will listen to arguments about stats and advanced metrics that suggest the argument between LeBron and Michael is a lot closer that we thought, and we might even entertain the idea that on many of those scales, especially in the postseason, LeBron was statistically better, but LeBron was never able to amass anything equivalent to “The Run” of six championships in a row (not counting retirement).

If Michael Jordan never existed, how many rings would Hakeem Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing, Charles Barkley, Clyde Drexler, and Malone and Stockton have? How many more would Magic, Bird, and Isiah have? How many different legacies would have been cemented with a ring, if he never existed? There’s a reason they call Michael Jordan the legacy killer.

If Michael Jordan never existed, how many rings would Hakeem Olajuwon, Patrick Ewing, Charles Barkley, Clyde Drexler, and Malone and Stockton have? How many more would Magic, Bird, and Isiah have? How many different legacies would have been cemented with a ring, if he never existed? There’s a reason they call Michael Jordan the legacy killer.

The counter argument might be, that if Michael Jordan had to compete against “The virtually unstoppable” David Robinson, Tim Duncan combo, the Kobe, Shaq combo, the LeBron, Kyrie combo, or Steph Curry and the Warriors ability to shoot the ball from outside the arena, he might not have had such an almost unprecedented run. Before we strip Jordan of his crown, however, we do need to go back those names of elite, hall of fame names from the era’s elite teams of its own “virtually unstoppable” combos and elite talent that Jordan and the Bulls defeated. Our conclusion matches that of the Reddit use who claimed: “There’s no evidence to support [the idea] that the [elite] players from the 90s are any better or worse than the [elite] players of today.”

Of all the biases involved in these arguments, the toughest to overcome is the emotional one. We can all argue our generational biases, as we all deem the best players of “our” era as the best to ever play the game. Others, from other eras, might argue that Bill Russell, Wilt, Dr. J, Pistol Pete, Oscar Robertson, Kareem, Magic and Bird, Isiah, Tim Duncan, Kobe, LeBron, Steph Curry, and Nikola Jokic were/are better, but these arguments focus on tangible elements of the game. No NBA player I’ve witnessed, in my life (and I admit to many biases to arrive at this conclusion), has combined elite talent with elite levels of doing anything and everything he had to to win better than Michael Jordan. His own teammates talk about how vicious and downright mean he could be to them during practice. He played psychological games with them, his opponents, and himself in order to gain some kind of edge for that series, or that night, for one win in a series. On some level, we have to throw the idea of biases and metrics out the window and put ourselves in Michael Jordan’s shoes. He had all the money in the world, he couldn’t leave his hotel room in most countries around the world, because of his fame, and he had every creature comfort a human being could dream up, but when one of his teams needed a win, he almost always came through in the final six years of his career as a Bull (the one series loss to the Shaq, Penny Hardaway-led Magic being the sole exception). Five of the six championships, during his much talked about run, were 4-2, six game wins. Each of them required him to dig deep to help his team find some way to overcome his opponent, and I’ve never seen another player will his team to win as often, or with as much consistency, as the greatest basketball player who ever lived, Michael Jordan.