Power, Greed, Corruption, and Murder in Nebraska? Small town, Nebraska? According to reports, the culture of crime, corruption and lawlessness in North Platte, Nebraska was so rampant that it was nicknamed “Little Chicago”. Little Chicago, as in gangsters, as in Al Capone. According to local lore, the town’s law enforcement was so lax during this era, that when various crime bosses and gangsters needed a place to cool off or lay low, they would “vacation” to North Platte, Nebraska.

A woman named Annie Cook (1875-1952) took full advantage of this climate by becoming a bootlegger during The Prohibition Era, a madam of a prostitution ring, and the superintendent of a poor farm that allegedly enslaved and murdered the indigent and destitute who worked on her farm.

Annie Cook built such a prosperous criminal empire that at her peak she was considered her one of the two most prominent criminal figures of North Platte (crime boss Al Hastings being the other). Yet, if we ran into this little woman at one of the church functions she held in her front yard, her smile, her “vanilla voice,” and pleasant demeanor might have reminded us of that cute, little old lady who quietly sits in the back corner of our church.

When I first heard the tale of an unusually awful woman turned gangster, I thought it had bestseller written all over it. When the former and current North Platters dropped the details of her criminal empire, I couldn’t believe no one documented this big secret of the Midwest before. The more they told me about this story, the more my smile faded.

“It wasn’t just innocent people Annie Cook maimed and murdered,” they told me. “Her victims were largely the old, the mentally challenged and the poverty-stricken. She mentally and physically tortured them, and she killed them when they became a financial burden to her.”

Prior to hearing that breakdown, I had this romanticized image of Annie Cook as the original female gangster, or OFG. The more I heard, the more difficult it became to imagine how anyone could romanticize her. We love our gangster flicks, because we love bad guys, and we love violence, as long as it’s justified and noble, or relatively noble.

Don Vito Corleone, the beloved main character of The Godfather, was a bad man, one of the most famous bad guys in fiction, but he only hurt and killed “those who chose this life.” Yet, if this fictional composite of influential figures in organized crime became the most powerful Don of the five families, what atrocities did he have to commit to get there? If a young, aspiring Vito Corleone vowed to only hurt “those who chose this life” and other dishonorable figures, his leader would’ve ordered him to hurt or kill an innocent person to prove loyalty. When Vito developed his first protection racket, what did he do to the mom and pop store owners who failed to pay on time? As a fictional tale of a composite character, author Mario Puzo and director Francis Ford Coppola could do away with the messy details of everything a gangster would have to do to become an all-powerful Don, but who were those influential figures from history on whom Don Vito Corleone was based, and who did they have to hurt and kill?

As the former and current North Platters continued to drop tale after tale on me, I began to realize that leaving out the messy details of the OFG’s rise to the top were almost impossible. The messy details were the story, and no author could omit them in their romanticized gangster tale.

The fact that Annie was able to break so many laws meant that she was above the law, and to me that made her a gangster. The other, messy details were so unusually awful that her tale couldn’t be classified as anything but a horror, a true horror, as opposed to the cinematic variety. These details were such that I realized I no longer had a “cool, female gangster who dominated a small, Midwestern town” tale on my hands, but one of a unusually awful woman who enjoyed hurting and killing the helpless, defenseless, and frail. The tale was so awful that I no longer had big, bestseller aspirations, but a tale that needed to be told.

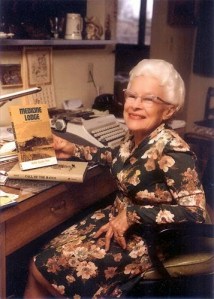

Much to my disappointment, I learned that Nellie Snyder Yost beat me to it with her Evil Obsession book. I was jealous, but I couldn’t wait to get my hands on it to see if she captured the essence of the Annie Cook story as I imagined it. Ms. Yost exceeded my expectations with her research, as she uncovered details that I consider some of the most horrific I’ve ever read, and I’ve read my fair share of True Crime books. Her research was also so thorough that she is now considered the foremost expert on Annie Cook, and very few have questioned the legitimacy of her claims (some locals claim the book blends fact with oral history at times.) Yet, if the claims Joe (Martin) Cook and Mary Knox Cauffman testified to in court are true, then Evil Obsession is one of the most uncomfortably disturbing recitation of facts that I’ve ever read, the type law enforcement officials spend a lifetime, often unsuccessfully, trying to forget.

How Little Annie Made it Big

In 1893, the 19-year-old, Anna “Annie” Maria Petzke thought she met her savior when she met Frank Cook. She thought he was as rich as she thought her family was, because he owned his own farm, and it came equipped with a white farmhouse and an irrigation ditch.

Suggesting that Annie was “saved” by Frank Cook invites the idea that Annie was enslaved by her Russian Immigrant parents on their Denver, Colorado farm. She wasn’t enslaved by her parents, as reports suggest she didn’t mind the work, but she and her sister Liz worked as hard as their brothers, and the Liz and Annie were never paid for their efforts. Their parents didn’t think women should have money.

Suggesting that Annie was “saved” by Frank Cook invites the idea that Annie was enslaved by her Russian Immigrant parents on their Denver, Colorado farm. She wasn’t enslaved by her parents, as reports suggest she didn’t mind the work, but she and her sister Liz worked as hard as their brothers, and the Liz and Annie were never paid for their efforts. Their parents didn’t think women should have money.

Farm life was the only life Anna Maria Petzke ever knew, as she was born and raised on a farm, so she likely didn’t have much knowledge of the outside world. She grew up envying her brothers for the money they made working on the farm, and she thought she had been cheated out of her share of what she considered the vast family fortune.

When Annie married Frank and saw his books, she had to be disappointed to discover that an 80-acre farm doesn’t make near as much money as she always thought, and she was just as disappointed to learn that Frank had little-to-no ambition to expand, buy more farms, and make more money. This led to discussions, arguments, and fights that culminated in Frank informing Annie that his goal in life was limited to generating enough income to support a family, and that he thought his 80-acre farm could do just that. That wasn’t enough for Annie, but she knew Frank well enough to know he was a rather passive man, and that she could dominate him. She knew it wouldn’t take much to convince Frank to buy more farmland to gain more money, and attain more power in the community, but it bothered her that as a woman of the late 1800s, early 1900s, in small town, Nebraska, she had to go through Frank to achieve this. She couldn’t figure out a way to do it on her own, until she experienced some nagging back pains.

After exhausting the efforts of the local physicians to relieve his wife of her nagging back pain, Frank gathered enough money to purchase Annie a train ride to Omaha, Nebraska, and he secured for her the services of a big city specialist. While sitting in the waiting room of that big city specialist, Annie had a chance meeting with a woman named Jane. Annie couldn’t know it at the time, but this chance encounter would change everything for her.

As ambitious as she was, Annie Cook probably would’ve found other paths to all the money she felt her family deprived her of in Denver, even if she never met Jane, but it’s just as likely that her definition of power and big-time money would’ve been limited by her station in life. It’s also likely that if Jane never groomed Annie into the world of prostitution, Annie’s unquenchable greed, lust for power, and blind ambition would have eventually put her on the radar of local law enforcement.

When she returned from Omaha, Annie informed Frank that while the Omaha specialist helped her find some relief from the pain, “The doctor said it was a chronic thing, that I’ll have to go back every now and then for treatment.” (The doctor told Annie she experienced a kidney dysfunction, he prescribed some medicine and told her to come back in a week.) How often she saw this specialist on her return trips to Omaha is unknown, but every time Annie returned to the city, she visited Jane.

Over the course of several visits, and lengthy stays in Omaha, Annie worked at Jane’s “Sporting House” learning, firsthand, how to run a brothel. Jane showed her how to conduct herself as a madam, and how to handle the workforce. Annie made a lot of money, fast, working as a madam for Jane. She paid off the debts she incurred with Jane, and she even managed to purchase a farm she always had her eye on. Annie probably didn’t know it at the time, but becoming a madam in North Platte would not only make her a lot of money, fast, but it would eventually play a prominent role in her dream of creating a criminal empire.

When Annie Cook decided to sell alcohol, and run her own distillery, during The Prohibition Era, she was never investigated for breaking the local, state, and federal laws of that era. Why she was never investigated by the various law enforcement agencies will be a recurring theme throughout this article, as Annie Cook knew how to make the right connections with a couple dollars here and there, and some suggest that her boarding house for girls bordello developed a client list of prominent officials that she built, maintained and used when she needed an issue to go away.

“Anne Cook had officials sign off on death certificates of people who died mysteriously on her farm.” —Panhandle News.

She also used those connections, coupled with numerous bribes and threats of extortion directed at those who frequented her boarding house for girls to help her secure the Lincoln County contract to provide housing, aid, and comfort for the poor and indigent. Annie managed to take that contract away from a kindly, decent widow named Mrs. Emma Pulver, who, by all accounts treated her guests with decency and respect for twenty-five years. Annie outbid the widow by demanding less in the way of government reimbursements for housing them and providing the aid and comfort for their care. We can only guess that Mrs. Pulver, the town, and county officials were shocked that Annie thought she could provide “guests” of Lincoln County care at a rate lower than Mrs. Pulver, but Annie probably told them that she thought the guests could make up for any lost revenue by allowing them to provide her the labor necessary for her farm. While that may have been true, Annie also made up for most of the lost revenue by denying the guests adequate food, heat, hygiene, and anything else she could think up to improve her bottom line.

It’s difficult to convey how awful Annie treated these guests for the next eleven years, except to write that she considered them her possessions from that point forward, and she could do with them what she wished. She basically enslaved the indigent and destitute on the farm, verbally and physically abusing, and some allege torturing them to get more production out of them. She had the guests of what was eventually called the Cook Poor Farm work long, labor-intensive hours without compensation of course, but she also deprived them of many of the necessities of life. At this point in the article we know the answer to the question, ‘Why wasn’t the Cook Poor Farm dinged for all these violations and eventually shut down?’ It survived investigations of the numerous charges made against it for eleven years, and the evidence suggests that the county officials in charge of helping Annie maintain the standards necessary for the quality of life for her guests were either on Annie’s payroll or client lists of her boarding house for girls.

The Unusually Awful Horror of Evil Obsession

“I didn’t like that movie,” a friend of mine said of a Phoef Sutton sports drama/thriller called The Fan. “It made me feel so uncomfortable that I walked out on it.”

“Isn’t that what you pay your hard-earned dollars for?” I asked. “Don’t you want movies and books of this sort to take you out of your comfort zone?” We both looked at each other from afar, as if we couldn’t understand the other’s extreme position.

The difference between the two of us was that she loved horror movies that knew how to keep it fun, acceptable, and lightweight. These popcorn pleasures don’t engage in disturbing truths about human nature, and they don’t lead us to feel sympathy or empathy for the victims. They keep their horror campy, and so over the top with blood and gore that it helps us distance ourselves from the horror. There’s nothing fun about Evil Obsession, and my friend wouldn’t have made it twenty pages in. There are no cats flying into scenes to provide jump scares. The big, bad monster of this tale doesn’t growl like a lion in any of the scenes, and she doesn’t say cool, dark, or quasi funny things before she kills someone. Annie Cook also didn’t try to develop a cool cause to justify her actions either, not in the manner our favorite serial killers or mass murderers do, and her unusually awful acts weren’t committed in a calculating manner the subjects of our favorite True Crime books are. Unless we consider killing useless human beings (by her definition) to improve her finances justifiable in the sense that she was denied money when she was younger, then she wasn’t motivated by righting wrongs either.

The best description we could use to describe most of the mysterious deaths that occurred around Annie Cook is that she quietly did away with the guests of the Cook Poor Farm when they became economically unviable for her. She caused their premature deaths through starvation and other slow, unceremonious measures that proved easy to mischaracterize by various officials. Thus, the horror of Evil Obsession is not theatrical or cinematic, it’s just a tale of a relatively ordinary woman who just happened to be so unusually awful that it makes us feel so uncomfortable to read about her.

Killing Clara

The one glaring exception to that methodology, and the most substantiated allegation of murder, corroborated by Annie’s sister Liz’s eye-witness testimony, suggests that Annie Cook got away with murdering her own daughter Clara. Yet, if Liz’s descriptions of that incident are 100% accurate, and the case made it to the state’s district attorney desk, he would probably seek the lesser charge of voluntary manslaughter to secure a conviction against Annie.

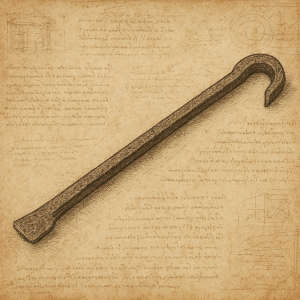

Annie’s sister Liz said that the mother and daughter were involved in a heated argument, but she said the two of them were often in heated, vicious, and sometimes violent arguments. Whether or not this argument was worse or par for the course is not stated, but when it reached a point that terrified Clara, she ran from the house to escape her mother. Annie gave chase and in a flurry of rage, she threw a cast-iron stove lifter at her thirty-eight-year-old daughter, hitting her on the head in such a manner that took the life of Clara Cook. Liz reports that the impact initially caused Clara to run around a tree three times before collapsing, as a chicken might after having its head cut off.

Annie’s sister Liz said that the mother and daughter were involved in a heated argument, but she said the two of them were often in heated, vicious, and sometimes violent arguments. Whether or not this argument was worse or par for the course is not stated, but when it reached a point that terrified Clara, she ran from the house to escape her mother. Annie gave chase and in a flurry of rage, she threw a cast-iron stove lifter at her thirty-eight-year-old daughter, hitting her on the head in such a manner that took the life of Clara Cook. Liz reports that the impact initially caused Clara to run around a tree three times before collapsing, as a chicken might after having its head cut off.

Annie reportedly went to her daughter’s aid and wrapped a bandage around her head. After Clara succumbed to death, Liz stated, Annie ordered Joe (Martin) Cook to retrieve a bag of money Clara had hidden in her room. If we take the circumstances out for a moment, Annie’s daughter is dead, and if Liz’s account is as immediate as it sounds, Annie remembered that Clara hid money in her room, and she ordered Joe to retrieve while her daughter’s corpse laid before her, still warm. Then, when we consider the circumstances, she caused her own daughter’s death, and rather than feel remorseful, she ordered Joe to retrieve it in case investigators happened upon it. Ms. Yost reports that Annie then used Clara’s money, combined with the insurance money from Clara’s death, to purchase a farm she always had her eye on. (After a brief, official investigation, it was officially discovered that Clara’s unfortunate demise was the result of an accidental poisoning.)

So, if we were to try to pitch this story to the “just the facts ma’am” crowd, the evidence suggests that we should remove that provocative, bestselling ‘M’ word murder from the back cover, unless that ‘M’ word were used to describe the mysterious death of Clara Cook, and all of the mysterious deaths that happened around Annie Cook.

“But rumor has it that several workers’ carcasses from her Cook Poor Farm were found in ditches shortly after their ill-fated escape attempts,” the concerned citizen might say. “Did your research show you that? Did your research show how many old and indigent patients, who could no longer work, ended up succumbing to mysteriously premature deaths?”

“But rumor has it that several workers’ carcasses from her Cook Poor Farm were found in ditches shortly after their ill-fated escape attempts,” the concerned citizen might say. “Did your research show you that? Did your research show how many old and indigent patients, who could no longer work, ended up succumbing to mysteriously premature deaths?”

“Fair enough,” we might say, “but no official records confirm those incidents.”

“Official records,” they might respond with exhaustion. “Where do you think this nickname “Little Chicago” came from? North Platte, Nebraska, in the early 20th century, was an absolute cesspool of corruption and lawlessness, and people were absolutely terrified of Annie Cook, because they knew she could get away with anything, including murder, because she did.”

“Anne Cook is an example of if officials weren’t able to be corrupted, they could have stood up to her,” said Jim Griffin, a local historian and Curator Director of the Lincoln County Historical Museum. “She bought off [and extorted] most of the town and council members to continue operating her ventures.”

No one knows, exactly, how many mysterious deaths occurred around Annie Cook, but educated guesses based on local lore and historical context suggest that Annie Cook may have been responsible for multiple deaths, possibly several dozen. Some of these mysterious deaths were the result of blatant acts of criminality of the highest order, and some slipped through the cracks of the bureaucratic foundation of the town.

One example of a mysterious death that occurred on the Cook Poor Farm involved a resident Annie called “that old bastard Kidder”. Old Kidder died of “old age and heart failure” according to the death certificate a county mortician named WR Munson wrote, signing for the county coroner. He wrote and signed the document for his good friend, Annie Cook, “ignoring the all too plain evidence that starvation caused, or contributed to, the death of the unfortunate pauper.” As superintendent of the Cook Poor Farm, Annie Cook was put in charge of this man’s welfare, and she allegedly denied this sickly man food. We can assume that she did it, because the cost of his care began affecting her bottom line. To her mind, Old Kidder overstayed his usefulness.

Who knows how much longer Old Kidder could’ve lived? We can only guess that he was a forgotten man, but who was he? How many people cared about this man, and why didn’t anyone step forward to question how this man died? If anyone aside from Liz, Munson, and Annie suspected foul play, why didn’t they step forward, and if they did who would act on the testimony that alluded to Annie’ s role in this man’s premature death, and who would act on that testimony? If a representative of the coroner’s office officially signs off on the death of a forgotten man that no one cared about, who would have called for a medicolegal investigation that involved a thorough examination of the death scene, interviews with witnesses, and collection of physical evidence? Who would call for an autopsy to prove or disprove initial findings? Starvation proved, in this case, a perfect crime for a well-connected, unusually awful person.

Another incident that went officially undocumented, involved the story of a teenager, named Allen Porter. The young Porter was driving his horse driven wagon to Annie Cook’s house to retrieve a potato digger she borrowed from Allen’s uncle. When they neared the Cook Estate, Allen’s otherwise obedient horses stubbornly refused to pass a wagon box left by the side of the road. After Allen continued to urge the horses onward, Allen reported, the horses’ legs began trembling. Frustrated, the young Porter pulled up to the wagon box to investigate the source of what he considered his horses’ irrational fears. He looked down into the box to see an old man staring up at him. The sight of a frail, old man in an old, abandoned wagon box probably knocked this young teenager back in shock. We can only guess what the young Allen Porter expected to find, but seeing an old man in there was probably the last thing he expected to see.

After he recovered from that initial shock, Allen Porter looked back in to study the old man looking back up at him, eyes wide and bulging, his face covered in flies. As horrific as it must’ve been for the young teenager to discover a corpse in the wagon box, his careful study of the poor, old man revealed the slight expansion and contraction of breath. The man was alive. We don’t know what was going through Porter’s head, or why he didn’t do more to help the poor, old man, but how many of us have experience with such inexplicably horrific matters? How many of us would know what to do? The young Porter was probably so shocked and terrified that he didn’t know what to do, so he rode onto the Cook Estate to try to put it out of mind. Once there, Annie exited her house to greet him. We don’t know how much of Porter’s path Annie saw, but when she met him, she greeted him with a suspicious “What do you want?” Allen told her, and she helped him load the potato digger into his wagon. When Allen took the potato digger back, he reported what he witnessed to his uncle, and the older man was not surprised. He reminded Allen to let the horses cool before watering them, and he turned away.

After he recovered from that initial shock, Allen Porter looked back in to study the old man looking back up at him, eyes wide and bulging, his face covered in flies. As horrific as it must’ve been for the young teenager to discover a corpse in the wagon box, his careful study of the poor, old man revealed the slight expansion and contraction of breath. The man was alive. We don’t know what was going through Porter’s head, or why he didn’t do more to help the poor, old man, but how many of us have experience with such inexplicably horrific matters? How many of us would know what to do? The young Porter was probably so shocked and terrified that he didn’t know what to do, so he rode onto the Cook Estate to try to put it out of mind. Once there, Annie exited her house to greet him. We don’t know how much of Porter’s path Annie saw, but when she met him, she greeted him with a suspicious “What do you want?” Allen told her, and she helped him load the potato digger into his wagon. When Allen took the potato digger back, he reported what he witnessed to his uncle, and the older man was not surprised. He reminded Allen to let the horses cool before watering them, and he turned away.

“Getting away with murder” is a hyperbolic expression we now use to describe someone acting badly without consequences. If our fellow employee loafs on the job, for instance, we say they’re getting away with murder when the boss doesn’t call them out on it. When foreigners hear us use this phrase, they wonder how we can say such an inflammatory phrase so casually. “Getting away with murder is just something we say,” we say. “It’s an expression.”

Even with their now archaic and antiquated technology, getting away with murder was considered one of the hardest things to do to early 20th century American citizens, and they probably dropped that line in the same somewhat sarcastic and serious ways we do today. How would an unusually awful person like Annie Cook respond to such a serious joke in her day? “All you have to do is prey on the unloved and unwanted that no one, if truth be told, wants around anymore. My victims became such a burden to society and their loved ones that if we could force them to be honest, they might actually thank someone like me for having the courage to off the useless peopler who has become such a drain on society and our resources. Before you do it, however, make such you make the necessary connections with prominent people for they can do a lot to help everyone else forget to do their jobs or neglect their responsibilities as good citizens. If you do it right, you can scare good men and women, like Allen’s uncle, into reminding their nephews about how to put the horses away.”

True horror, as opposed to the more theatrical or cinematic, can be found in the ways in which unusually awful people display an utter disregard for the sanctity of life, human life. The horror is in the details of an unusually awful person asking us to be honest and acknowledge that some human life just isn’t special. Some life is an unprofitable burden, and it often overstays its usefulness.

The conclusion of this chapter is that there is no conclusion, as Annie Cook never had to put up with nosy neighbors in North Platte or Hershey, Nebraska, learning things about her. They were terrified of her, and they gave her the much needed privacy she needed to conduct her affairs the way she saw fit. There were never any investigations from law enforcement officials, as they were bought, extorted, or informed that their investigations would go nowhere. Annie Cook also never had to deal with exposés in the media, as there were never any stories done about her during her day. Reading through this story, it almost seems impossible that some young, enterprising young reporter wouldn’t leap the hurdles to overcome the corruption in these towns to produce an award-winning exposé of the killing fields in North Platte and Hershey.

“But you just reported on the climate inherent in these towns, people were terrified, and they were all very hush hush on the topic of Annie Cook and her Cook Poor Farm,” you might say. “I doubt the best reporter or law enforcement official could get anything out of them to do their job.” When Ms. Yost finally decided to write Evil Obsession, she expected to encounter these roadblocks. To her surprise, “All the informants seemed willing, even eager, to tell me what they knew.” Granted, this book came out in 1991, decades after Annie Cook’s death, but where was that eager reporter, looking to expose the travesties occurring at the Cook Poor Farm while they were going on, and where was that reporter in the intervening years, decades, between Annie Cook’s death and Ms. Yost’s decision to research, write, and publish Evil Obsession? If it wasn’t for Ms. Yost, Annie Cook’s legacy probably wouldn’t have suffered either, because there were no official investigations of the mysterious deaths that occurred in and around Cook Poor Farm and the Cook Family Estate in the aftermath of her death. There is also no record of post-mortem investigations, or any cold cases being officially re-opened in the decades since, and the absence of evidence has become part of the legacy and myth of the unusually awful Annie Cook, and that legacy is a stark reminder that horror, true horror lies not in cinematic monsters but in the indifference that lets figures like Annie prey on the “useless” and forgotten.