“Watch Alien: Romulus,” a friend of mine said. “It’s special.”

I loved that characterization. It was so simple that I wish I thought of it first. To set up the backdrop to this characterization, my friend and I have a long history of spoiling movies for one another by overhyping them. “The greatest movie ever!” we said a couple times. “Top ten in the genre,” we said, specifically listing the genre. By saying the movie was special, I think my friend was hoping I would see the movie, but he wanted me to see it, and judge it, even, or without hype. I’ve been on both ends of this. I am superlative man! I’ve ruined more than a few movies for others by going so far over the top that the recipients of my superlatives couldn’t help but consider it “Good, don’t get me wrong, but you were going so ape-stuff over it that I watched it thinking it would be the greatest movie ever made.” I’ve been on the other end of that too, and I’ve watched movies others hyped up for me, eager for that movie to absolutely blow my mind. What do we do? We “meh” our way through it, and then, we return to our friend the next day and say, “It was good, don’t get me wrong, but top-10? I don’t think so.” It’s entirely possible that if we didn’t plant these GOAT eggs on one another, we might’ve considered the movie in question as great as they did. As we all know, distinguishing good, bad, great, and awful can often be all about the mindset we have walking into the theater. So, from this point forward, I am going to adopt my friend’s “special” characterization for any movies, books, or music I hear, and I’m going officially declare to anyone reading the following list of all of my superlatives, regarding the “greatest works of art of all time!” that with the powers vested in me, as the writer of this article, it’s special.

I loved that characterization. It was so simple that I wish I thought of it first. To set up the backdrop to this characterization, my friend and I have a long history of spoiling movies for one another by overhyping them. “The greatest movie ever!” we said a couple times. “Top ten in the genre,” we said, specifically listing the genre. By saying the movie was special, I think my friend was hoping I would see the movie, but he wanted me to see it, and judge it, even, or without hype. I’ve been on both ends of this. I am superlative man! I’ve ruined more than a few movies for others by going so far over the top that the recipients of my superlatives couldn’t help but consider it “Good, don’t get me wrong, but you were going so ape-stuff over it that I watched it thinking it would be the greatest movie ever made.” I’ve been on the other end of that too, and I’ve watched movies others hyped up for me, eager for that movie to absolutely blow my mind. What do we do? We “meh” our way through it, and then, we return to our friend the next day and say, “It was good, don’t get me wrong, but top-10? I don’t think so.” It’s entirely possible that if we didn’t plant these GOAT eggs on one another, we might’ve considered the movie in question as great as they did. As we all know, distinguishing good, bad, great, and awful can often be all about the mindset we have walking into the theater. So, from this point forward, I am going to adopt my friend’s “special” characterization for any movies, books, or music I hear, and I’m going officially declare to anyone reading the following list of all of my superlatives, regarding the “greatest works of art of all time!” that with the powers vested in me, as the writer of this article, it’s special.

Merriam-Webster defines special as “Distinguished by some unusual qualities.” Other resources list it as, “Better, greater, or otherwise different from what is usual.” My personal definition of special is different, as in a different kind of genius. Some label special geniuses, disruptors, because they dare to be different. They dare to tackle their projects in a way that either no one ever considered before, or they thought it violated some tenet of their definition of art. I choose to dismiss the “better and greater” definition of special, because unusual and different often get lost in debates of quality. Debates over quality often invite technical qualities I know nothing about. I often expose my ignorance in technical quality debates, because I view most technical qualities as trivial. I know special though, and that characterization often leads to ‘Ok, what do you know?’ questions. “I don’t know,” I say paraphrasing a Supreme Court Justice, “but I know it when I see it.”

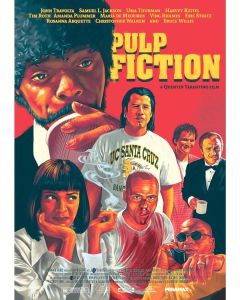

If Quentin Tarantino died shortly after making Pulp Fiction, he would still go down as a special genius. Some of my friends didn’t enjoy the movie for a variety of reasons, but they still saw it. Just about every single one of them admitted that it had special qualities. If I attempted to dissect the technical qualities of this film, I would display my ignorance on the subject, but suffice it to say that among all of the reasons this movie was special, the primary one was dialog. Some suggest Tarantino worked for ten years to perfect the dialog, and it shows. Bruce Willis claimed it was the only movie he ever worked on that didn’t have one single rewrite. There were so many incredible and unforgettable scenes in the movie Pulp Fiction that we could bog this entire article down with a play-by-play dissection of each scene, but we’ll focus on three of the highlights. The dialog between Vincent and Jules in the introductory scenes was special, because the careful word choices defined the characters with such immediacy, and the action scenes in the apartment were so over the top that they were funny, horrific, and funny/horrific. The countering scene, later in the movie, between Butch and Fabienne, was just as special for its delicate and deft subtlety. The scenes between Vincent and Mia had special, influential and transcendental dialog, and the scene in the restaurant—sans the overrated dance scene—was unforgettable. Even while watching the movie for the first time, in a dingy, old theater long since closed, I experienced a tingle that suggested I might be watching the most special movie I’ve ever seen. I didn’t need to unearth its special qualities in the conversation I had leaving the theater, or read critical reviews to enhance those beliefs, I knew Pulp Fiction was special while sitting in the theater watching it for the first time, and it might be the single most enjoyable experience I ever had in the ever-dwindling experiences I’ve had in a theater.

If Quentin Tarantino died shortly after making Pulp Fiction, he would still go down as a special genius. Some of my friends didn’t enjoy the movie for a variety of reasons, but they still saw it. Just about every single one of them admitted that it had special qualities. If I attempted to dissect the technical qualities of this film, I would display my ignorance on the subject, but suffice it to say that among all of the reasons this movie was special, the primary one was dialog. Some suggest Tarantino worked for ten years to perfect the dialog, and it shows. Bruce Willis claimed it was the only movie he ever worked on that didn’t have one single rewrite. There were so many incredible and unforgettable scenes in the movie Pulp Fiction that we could bog this entire article down with a play-by-play dissection of each scene, but we’ll focus on three of the highlights. The dialog between Vincent and Jules in the introductory scenes was special, because the careful word choices defined the characters with such immediacy, and the action scenes in the apartment were so over the top that they were funny, horrific, and funny/horrific. The countering scene, later in the movie, between Butch and Fabienne, was just as special for its delicate and deft subtlety. The scenes between Vincent and Mia had special, influential and transcendental dialog, and the scene in the restaurant—sans the overrated dance scene—was unforgettable. Even while watching the movie for the first time, in a dingy, old theater long since closed, I experienced a tingle that suggested I might be watching the most special movie I’ve ever seen. I didn’t need to unearth its special qualities in the conversation I had leaving the theater, or read critical reviews to enhance those beliefs, I knew Pulp Fiction was special while sitting in the theater watching it for the first time, and it might be the single most enjoyable experience I ever had in the ever-dwindling experiences I’ve had in a theater.

Mother Love Bone’s Apple was special. I’ve had debates with musicians and other music freaks who know far more about music than I do, and they suggest that the lyrics on Apple were campy, silly, sophomoric, and hippy-trippy lyrics that haven’t aged well. It might suggest that I’m a campy, silly, sophomoric person who hasn’t aged well, because no matter how often I’ve heard and read those complaints, I still don’t see it. To my mind, Andrew Wood was an unusual genius when it came to writing lyrics. After lead singer his premature death, some of the band members reformed with a new lead singer, and formed Pearl Jam. “Ten was superior to Apple in every way, shape, and form,” my musician friend informed me, “and Eddie Vedder was a better lyricist, and he had a better voice.” My goal here is not to criticize Ten, Pearl Jam, or Eddie Vedder, as I enjoyed them for what they were, but they weren’t special to me. I rarely paid attention to lyrics before Apple, and I rarely have since, but Andrew Wood’s lyrics, his Andy-isms, as his bandmates called them, were special. They were funny, campy, sophomoric, and hippy-trippy, but they exhibited an unusual quality I still call “special” thirty-plus-years later.

Mother Love Bone’s Apple was special. I’ve had debates with musicians and other music freaks who know far more about music than I do, and they suggest that the lyrics on Apple were campy, silly, sophomoric, and hippy-trippy lyrics that haven’t aged well. It might suggest that I’m a campy, silly, sophomoric person who hasn’t aged well, because no matter how often I’ve heard and read those complaints, I still don’t see it. To my mind, Andrew Wood was an unusual genius when it came to writing lyrics. After lead singer his premature death, some of the band members reformed with a new lead singer, and formed Pearl Jam. “Ten was superior to Apple in every way, shape, and form,” my musician friend informed me, “and Eddie Vedder was a better lyricist, and he had a better voice.” My goal here is not to criticize Ten, Pearl Jam, or Eddie Vedder, as I enjoyed them for what they were, but they weren’t special to me. I rarely paid attention to lyrics before Apple, and I rarely have since, but Andrew Wood’s lyrics, his Andy-isms, as his bandmates called them, were special. They were funny, campy, sophomoric, and hippy-trippy, but they exhibited an unusual quality I still call “special” thirty-plus-years later.

You are Not so Smart by David McRaney. “It is far easier to entertain than it is to educate,” someone once said. If that’s true, it takes a special kind of genius to do both at the same time. Some pop psychology books focus on being entertaining, but they are so base, negative, and shocking. Others are so serious that they sound professorial. It takes a special author to combine a special talent for dry humor and wit with professorial scholarship on a subject, and McRaney accomplished that with gusto. What this author did, more than any other, was teach this writer how to tackle serious subjects in an entertaining fashion. He also laid a blueprint for me to understand how to apply everyday situations to larger concepts, a blueprint I’ve pursued ever since. To my mind, You are Not so Smart would be an excellent companion piece for Psych 101 classes, because I think students, who get the dreaded dry eyeball ten sentences into their gargantuan, dry textbooks, would love the learning while laughing arsenal Mr. McRaney employed while writing this book.

Whereas Pulp Fiction is in-your-face brilliant with quick, hip dialog, quick scene switches, and unforgettable music, the Coen Brothers invoke a more deliberate pace with quiet, casual dialog and more traditional music. I might be different from most Coen Brothers’ freaks, because I don’t think I ever “Wow!”-ed my way out of the theater with whomever I watched it. When I gathered with my friends later, and we remembered our favorite scenes, themes, and chunks of dialog together, I realize how brilliant that movie was. With all that in mind, I watched it again. It might be the way my mind works, but I think appreciation of the full breadth of the brilliance of a Coen brothers movie often requires a gathering storm of adoration. Fargo may have been the only one of their movies that hit me over the head with its brilliance, but I still had to talk about it and view it again to reach that “Wow!” factor. The Big Lebowski, Oh Brother Where Art Thou?, and Barton Fink all required some seasoning before I recognized how special they were.

Whereas Pulp Fiction is in-your-face brilliant with quick, hip dialog, quick scene switches, and unforgettable music, the Coen Brothers invoke a more deliberate pace with quiet, casual dialog and more traditional music. I might be different from most Coen Brothers’ freaks, because I don’t think I ever “Wow!”-ed my way out of the theater with whomever I watched it. When I gathered with my friends later, and we remembered our favorite scenes, themes, and chunks of dialog together, I realize how brilliant that movie was. With all that in mind, I watched it again. It might be the way my mind works, but I think appreciation of the full breadth of the brilliance of a Coen brothers movie often requires a gathering storm of adoration. Fargo may have been the only one of their movies that hit me over the head with its brilliance, but I still had to talk about it and view it again to reach that “Wow!” factor. The Big Lebowski, Oh Brother Where Art Thou?, and Barton Fink all required some seasoning before I recognized how special they were.

Our follow-up question to the Truman Capote quote, “You only need to write one great book” is, “What are you talking about?” In our ‘What have you done for me lately?’ society, we all love to say, “You think that guy’s a special genius, because I thought his last movie [album or book] sucked!” We love to say that about our special artists, because we all know they’re special, and we love to tear down facades. What I think Capote was saying is the author only needs one great book, album, or movie for the rest of us to know their author is special. If he comes out with 20 more works of art, we’ll probably buy ten of his other works before we realize he only had one in him. We’ll probably keep tabs on him too, “Did you read his latest? Is it any good?” We do this, because he really moved us once. His clever arrangement of words, reached us in a way so few do, and they really only have to do this once to start our love affair.

It’s often difficult to express the special nature of watching a movie in a movie theater for the first time to younger people who now watch an overwhelming majority of the movies they watch on streaming platforms. All of the hype and planning behind trying to get someone to watch it with us was a production in its own right. When we found someone who was as excited as we were to watch the special director’s next movie, we said, “Let’s do it,” and when that movie premiered that Friday, we got together and experienced it together, with a room full of strangers and friend, with popcorn and soda in our lap. It was an “event”. I know some young people still do it, and I stream movies as much as anyone else now, but I think we all miss the event status of what it once was.

It’s often difficult to express the special nature of watching a movie in a movie theater for the first time to younger people who now watch an overwhelming majority of the movies they watch on streaming platforms. All of the hype and planning behind trying to get someone to watch it with us was a production in its own right. When we found someone who was as excited as we were to watch the special director’s next movie, we said, “Let’s do it,” and when that movie premiered that Friday, we got together and experienced it together, with a room full of strangers and friend, with popcorn and soda in our lap. It was an “event”. I know some young people still do it, and I stream movies as much as anyone else now, but I think we all miss the event status of what it once was.

There was also something special about holding a physical album, cassette, or compact disc in your hands, before sliding it into a player and cracking the binding of our brand new book. As a hyper kid who only wanted to do physical things, I became an avid book lover as I aged into adulthood. I loved reading a book in public. I felt like I was finally a part of a club, and I enjoyed holding a physical copy of that book in my hands while flipping the pages. That’s almost entirely gone, and there’s something about the waiting that is gone too. Again, I could be overhyping the individual’s experiences, but I don’t think anyone eagerly anticipates the arrival of a new movie, book, album, or TV show. I had a hate/love relationship with waiting, similar to a child hating and loving the days until Christmas. We used to ‘X’ off the days on the calendar, until our favorite product would finally make it to store shelves, we’d talk to fellow fans, and build ourselves into a lather until it finally arrived. I could be exaggerating in this regard, but these products just seem to appear now, and we click on it. We might “know” that our favorite author is going to deliver a product to a streaming service sometime in the near future, but do we still eagerly anticipate its arrival? I know I don’t. It’s just there one day, and I click on it.

“In the grand scheme of things, what’s the difference between clicking on something and watching, listening and reading it? Once we’re halfway through it, if it’s great it’s great, and it can still achieve the same special status if it’s that good.” That is all true, but holding a physical copy of the product, even if momentarily renting it from Blockbuster, used to give the consumer of the product some level of ownership that created a “special” relationship with its creator that streaming cannot replicate. Some of us dreamed of this day, and when Napster first appeared, then iTunes, it felt like a realization of that dream, and we loved creating playlists to ‘X’ out some of the more boring deep cuts, but now that it’s all here, and we’re a couple decades into being used to it, some of the “special” event status of it is gone.

I still remember some of the “special” theatrical experiences I had. I remember where I saw this movie, and I still remember watching that movie with a group of friends and strangers, who enhanced my theatrical experience in a way only a group can. One of the movies I watched in a theater was not even that good, it was too long, and it tried too hard, but the theatrical experience I had that day was so “special” that I still remember it fondly, almost romantically. I remember the car I owned, and the street corner I passed in that car, the first time I realized the music I was listening to was the work of an unusual and special genius. I also remember the chair I sat in, the breakroom I read in, and the bathtub I laid in reading the works of genius, because, for me, to quote the group Climax, featuring Sonny Geraci, “Precious and few are the moments we two can share.”

{Editor’s note, we did eventually see Alien: Romulus, and it was special, but we think we might have ruined the total experience that makes such movies special by watching it via a streaming service. Watching a comedy, or a more typical drama, can be appreciated in either format, but a great horror, sci-fi, or those rare masterpieces needs to be viewed in groups, in a dark theater, with popcorn and soda in your lap or drink holder.}