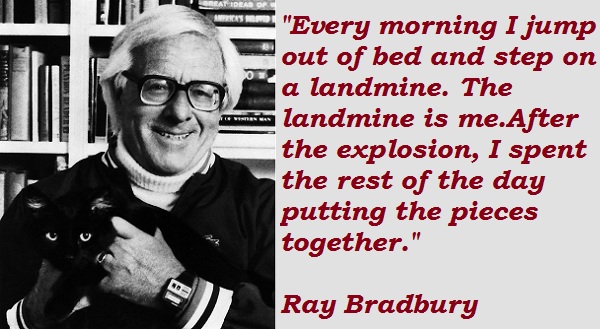

“You need to find your own truth,” Ray Bradbury said to a caller of a radio show on which he was a guest. Mr. Bradbury expounded on the idea, somewhat, but he remained vague. He said some things about following the lead of influential masters of the craft, and all that, “But you’ll eventually need to find your own truth,”

We loathe vague advice. We want answers, thorough and perfect answers, that help us cross bridges. We also want those answers to be pointed and easy to incorporate, but another part of us knows that the seeker of easy paths often gets what they pay for in that regard.

When we listen to a radio show guesting a master craftsman, however, we expect nuggets of information to unlock the mystery of how a master craftsman managed to carve out a niche in his overpopulated craft. We want tidbits, words of wisdom about design, and/or habits we can imitate and emulate, until we reach a point where we don’t feel so alone in our structure. Vague advice and vague platitudes feel like a waste of our time. Especially when that advice comes so close to our personal core and stops abrupt.

Ray Bradbury went onto define his vision of an artistic truth as he saw it, as a guest on this radio show, but that definition didn’t step much beyond the precipice. I tuned him out by the time he began speaking of other matters, and I eventually turned the channel. I might have missed some great advice, but I was frustrated.

After I heard the advice, but I went back to doing what I was doing soon after hearing it, because he didn’t give me what I wanted and needed at the time. It did start popping up when I was doing something, and then it started popping up when I started doing something else. The advice initially felt like useless new-age advice we give to confused souls looking for guidance. It felt like sage advice from some kind of guru who never figured out how to succeed within normal structures in life, so he began dispensing gobbledy gook that others should interpret but never can, so they just label the guru a spiritual guide, because they don’t know what else to call him.

It might take hours, it might take weeks, but this idea of an individual truth, as it pertains specifically to artistic vision, becomes applicable so often and, in so many situations, that we begin to chew on it and digest it. Others may continue to find this vague advice about an artistic truth nothing more than waste matter –to bring this analogy to its biological conclusion– but it begins to infiltrate everything the eager student does. If the advice is pertinent, the recipient begins spotting truths what should’ve been so obvious before. They begin to see that what they thought was their artistic truth, and what their primary influences considered true, is not as true for them as they once thought.

Vague advice might seem inconsequential to those who do not bump up against the precipice. For these people, a platitude such as, “Find your own truth” may have an “of course” suffix attached to it. “Of course an artist needs to find their artistic truth when approaching an artistic project,” they say. “Isn’t that the very definition of art?” It is, but if we were to ask an artist about the current project they’re working on, and its relation to their definition of an artistic truth, they will surely reply that they think they’re really onto something. If we ask them about the project after they finish the piece, we will likely receive a revelation of the artist’s frustration in one form or another, as most art involves the pursuit of an artistic truth coupled with an inability to ever capture it to the artist’s satisfaction. Yet, we could say that the pursuit of artistic truth, coupled with the frustration of never achieving it, provides more fuel to the artist than an actual, final, arrived-upon truth ever could.

Finding an artistic truth, involves intensive knowledge of the rules of a craft, locating the parameters of the artist’s ability, finding their formula within, and whittling. Any individual who has ever attempted to create art has started with a master’s template in mind. The aspiring, young artist tries to imitate and emulate that master’s design, and they wonder what that master might do in moments of artistic uncertainty: Can I do this? What would they do? Should I do that? Is my truth nestled somewhere inside all of that awaiting further exploration? At a furthered point in the process, the artist discovers other truths, including artistic truths that contradict prior truths, until all truths become falsehoods when compared to the current artistic truth. This is where the whittling begins.

In a manner similar to the whittler whittling away at a stick to create form, the storyteller is always whittling. He’s whittling when he writes. He’s whittling when he reads. He’s whittling in a movie theater, spotting subplots and subtext that his fellow moviegoers might not see. He’s whittling when we tell him about our experience at the used car dealership. He’s trying to get to the core of the tale, a core the storyteller might not see.

“I could tell you about the greatest adventure tale ever told, or a story that everyone agrees is the funniest they’ve ever heard,” she says, “and you’d focus on the part where I said the instead of the.” The whittler searches for the truth, or a subjective truth that he can use. Is it the truth, or the truth? It doesn’t matter, because he doesn’t believe that the storyteller’s representation of the truth is the truth.

Once the artist has learned all the rules, defined the parameters, and found his own formula within a study of a master’s template, and all the templates that contradict that master template, it is time for him to branch out and find his own artistic truth.

The Narrative Essay

Even while scouring the read-if-you-like (RIYL) links the various outlets provide for the books I’ve enjoyed previously, I knew that the narrative essay existed. Just as I’ve always known that the strawberry existed, I knew about the form some call memoir, also known as literary non-fiction or creative non-fiction, but have you ever tasted a strawberry that caused you to flirt with the idea of eating nothing but strawberries for the rest of your life? If you have, your enjoyment probably had more to do with your diet prior to eating that strawberry than the actual flavor of the inexplicably delicious fruit. In the course of one’s life, a person might accidentally indulge in a diet that leaves them vitamin deficient, and they might not know the carelessness of their ways until they take that first bite of the little heart-shaped berry.

“You simply must try these strawberries,” a co-worker said in a buffet line at the office. I have always loved strawberries, but I didn’t even notice these particular strawberries in the shadow of the glorious array of meats and carbs at the other end of the buffet. While I stood there, impatiently waiting for the slow forking procedures some have for finding the perfect piece of meat, she gave me a look. “Just try them,” she said. I did.

Prior to eating that strawberry, I knew nothing about chemical rewards the brain offers for fulfilling a need, and I didn’t know anything about it after I took that first bite either. The only thing I knew, or thought, was that that strawberry was so delicious that I experienced a temporary feeling of euphoria. I piled some strawberries on my plate, and ate a couple of them, but the line was so slow that I was allowed to eat a number of the strawberries on my plate before progressing. I normally do not do this, and I normally loathe those people who do. I prefer to assemble a meal for myself and wait until I’m at a table before I even take my first bite. My co-worker was so insistent that I try one, that I bit into to one to indulge her.

“These things are glorious,” I said.

“What are?”

“The strawberries.”

“Oh, right,” she said. “I told you.”

The sixth and seventh strawberries were as glorious as the first few, and before I knew it, I was gorging on the fruit when another friend behind me, in the buffet line, informed me that I was holding up the line.

At this point, the reader might like to know the title of the one gorgeous little narrative essay that spawned my feelings of creative euphoria. The only answer I can give is that one essay will not quench those suffering from a nutrient depletion any more than a single strawberry can. You might need to gorge on them in the rude, obsessive manner I did that day in the buffet line. One narrative essay did not provide a eureka-style epiphany that led me to understanding of all the creative avenues worthy of exploration in the form. One essay did not quench the idea depletion I experienced in the time-tested formulas and notions I had of the world of storytelling. I just knew I needed something more and something different, and I read all the narrative essays I could find in a manner equivalent to the effort I put into exploring the maximum benefits the strawberry could provide, until a grocery store checker proclaimed that she never witnessed anyone purchase as many strawberries as I was in one transaction. She even called a fellow employee over to witness the spectacle I laid out on her conveyor belt. The unspoken critique between the two was that no wife would permit a man to make such an exaggerated, imbalanced purchase, so I must be a self-indulgent bachelor.

An unprecedented amount of strawberries did not provide me with an unprecedented amount of euphoria, of course, as the brain appears to only provide euphoric chemical rewards for satisfying a severe depletion, but the chemical rewards of finding my own truth, in the narrative essay format, have proven almost endless. The same holds true for the rewards I’ve experienced reading the output of others who have reached their creative peaks. I knew narrative essays existed, as I said, but I considered most to be dry, personal essays that attempted to describe the cute, funny things that happened to them on their way to 40. I never thought of them as a vehicle for the exploration of the answers to our abundant questions on how to be, become, and live in the stories written by those authors who accomplished it.

It is difficult to describe an epiphany to a person who has never experienced one or even to those who have. The variables are so unique that they can be difficult to describe to a listener donning an of-course face. More often than not, an epiphany does not involve the provocative shock of unique, ingenious thoughts. My personal definition involves all of the of-course thoughts nestled among commonplace events and conversations that one has to arrive at by their own accord. When such an explanation doesn’t make a dent in the of-course faces, we can only conclude that epiphanies are almost entirely personal.

For me, the narrative essay was an avenue to the truth my mind craved, and I might have never have ventured down that path had Ray Bradbury’s vague four words “Find your own truth,” failed to register. For those who stubbornly maintain their of-course faces in the shadow of the maxim the late, great Ray Bradbury, I offer another vague piece of advice that the late, great Rodney Dangerfield offered to an aspiring, young comedian: “You’ll figure it out.”

If advice such as these two nuggets appear so obvious that it is considered unworthy of discussion, or the reader cannot see how to apply it, no matter how much time they spend thinking about it, adding to it, or whittling away at it to find a worthy core, I add this: You’ll either figure it out, or you won’t.