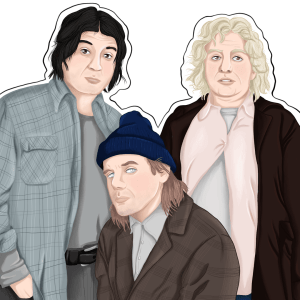

“Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darryl, and this is my other brother Darryl,” the actor William Sanderson, playing Larry, would say to introduce he and brothers Darryl played by Tony Papenfuss and John Voldstad on the Newhart show. With the passing of the actor Bob Newhart, and all of these retrospectives on his career, one would think someone, somewhere would break ranks and tell the story behind one of the most iconic and oddest running gags in television history. So far, nothing, silence, crickets!

It feels a little odd to call this line a catchphrase, because it’s not a phrase, and it’s not catchy, but it was repeated so often that we could at least call it a running gag of one of the most popular shows of its era. It was such an odd part of the show that one would think that everyone from the studio execs to the cast members themselves would demand some sort of explanation, backstory, or point of origin for the audience. (To my knowledge, there was never an in-show explanation.) We also wonder why, thirty-years since the show last aired, no one has ever taken credit for the line, told the insider story on how many hurdles it surely had to cross to before making it on air, and how it evolved from a simple introduction to a cultural staple. (My guess is it was a throwaway line someone threw in as a lark, and test audiences reacted so well to it that they decided to keep it in.)

Newhart aired from 1982-1990, so it came about in an era where the demand for catchphrases, from sitcoms, was just starting to wane a little. This isn’t to say that the catchphrase died, because it probably never will, but prior to Newhart, every sitcom was almost required to have a catchphrase, but this was no longer the case when Newhart aired. My assumption is that the writers never intended for this to be the show’s catchphrase, and my guess is they probably didn’t want a catchphrase at all, but if you even mentioned the show Newhart to a bunch of people, during this era, someone said, “I love Larry, his brother Darryl, and his other brother Darryl.” The intro to the eccentric woodsmen caught fire, and before I knew it, everyone I knew was saying it in one way or another.

Most shows from the 70s to the early 80s developed catchphrases to help audiences quickly identify with the characters on their show. Just about every popular show from this era had a catchphrase, and rather than try to list them all, we suggest you go to Flashbak.com for a top 25 list of the best catchphrases from the 70s, or you can go to Ranker.com for a list of the top 80s catchphrases. Characterization can be difficult and time-consuming of course, depending on the character, but screenwriters of TV shows needed something more immediate to help audiences identify quickly. Some of the times, networks only bought four-to-six episodes after the pilot to see if these shows could establish themselves, so the writers, the cast, and all of the others involved in the production knew they had to develop and characterize quickly, thus they created a word or phrase to help audiences relate to their characters quickly.

They also had to use these words and phrases to accomplish a wide variety of things, other than characterization, quickly. They had to sum up everything about the character, they needed it to be fun and silly, and the phrase had to be a malleable word or phase that the writers and actors could use to match a wide variety of situations.

We all attached these shows to their catchphrases, and we all repeated them, because we all watched the same shows back then. Even if we didn’t watch the shows, we knew the phrases, because everyone we knew said them. The actors responsible for reading these lines said they couldn’t go anywhere in the United States without someone dropping the catchphrase on them, and some of them have tales of traveling to remote, third world locations where the locals would drop an ‘Aayyy’ or a ‘Kiss my grits’ on them.

We all attached these shows to their catchphrases, and we all repeated them, because we all watched the same shows back then. Even if we didn’t watch the shows, we knew the phrases, because everyone we knew said them. The actors responsible for reading these lines said they couldn’t go anywhere in the United States without someone dropping the catchphrase on them, and some of them have tales of traveling to remote, third world locations where the locals would drop an ‘Aayyy’ or a ‘Kiss my grits’ on them.

If someone dropped the phrase on you, and you never heard it before, their response was usually laced with ridicule, “How could you have never heard this phrase before? Do you not watch TV, leave your home, or talk to other people?” We had three channels back then, and if we wanted to know what other people were talking about, or have friends of any kind, we knew we had to watch these shows.

For those who weren’t around during the 1982-1990 era, we all tried to come up with our own variations of “Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darryl, and this is my other brother Darryl”. I had three friends named Adanna, Madonna and Lisa. When they hung out together, they decided to mess with the strange fellas they would meet in bars by introducing themselves, “Hi, I’m Adanna, and this is my friend Madonna, and my other friend Donna.” It was funny at the time, but it was probably funny because I was there, and I knew them. It might be one of those ‘you had to be there’ jokes for which you had to be there, but the point of retelling this is that this ‘Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darryl, and this is my other brother Darryl’ joke was everywhere for a time.

With the passing of Bob Newhart, we might read writers of various publications attempt to eulogize him by placing his shows The Bob Newhart Show and Newhart in the upper echelons of quality programming. They weren’t, in my opinion. They were occasionally funny shows that weren’t extremely influential. Bob Newhart played the straight man to the silliness around him, and silly and funny gags and lines developed around this premise, but neither show was groundbreaking in situational comedy, and neither of them were headline stopping influencers. They were just occasionally funny sitcoms.

‘Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darry, and this is my other brother Darryl’ also managed to have an insider/outsider quality attached to it. We all repeated the joke, and tried to develop clever ways of twisting it to those who would ‘get it’, and those who ‘got it’ were insiders, but the show was so popular for a time that everyone got it. We considered it a slightly quirky, clever way of describing salt of the earth type characters that added some backwater qualities to those who exhibited some physical characteristics that matched the three brothers. The question we never asked back then is who came up with this line, and what was their thinking? Was there an origin story, or some kind of backstory behind it? Was it a result of success, failure, or success through failure?

Was the joke a result of some typo in the original bible the head writer wrote for the show? We don’t know. Was there an original third brother, who had a name like Elmer, but the two actors were both mistakenly cast as the character Darryl, which led to an argument between the actors? Did one of the writers note the confusion and decide to pacify both actors by calling them both Darryl, and it turned into an inside joke that eventually leaked into the script? We don’t know. Did an original writer come up with an equally banal name, like Elmer, and the writers decided that name might be too on-the-nose for a backwoods hillbilly? Did the writers want a different, subtle, and unstated characterization of the brothers’ parents that illustrated the family’s backwoods nature by giving the same name to two different sons? Or, did some ingenious writer just spontaneously shout out, “Let’s just name the other brother Darryl too?”

Was the joke a result of some typo in the original bible the head writer wrote for the show? We don’t know. Was there an original third brother, who had a name like Elmer, but the two actors were both mistakenly cast as the character Darryl, which led to an argument between the actors? Did one of the writers note the confusion and decide to pacify both actors by calling them both Darryl, and it turned into an inside joke that eventually leaked into the script? We don’t know. Did an original writer come up with an equally banal name, like Elmer, and the writers decided that name might be too on-the-nose for a backwoods hillbilly? Did the writers want a different, subtle, and unstated characterization of the brothers’ parents that illustrated the family’s backwoods nature by giving the same name to two different sons? Or, did some ingenious writer just spontaneously shout out, “Let’s just name the other brother Darryl too?”

“That is the ultimate taboo,” I imagine the head writer saying. “You can’t have two characters have the same name in a production. It will prove too confusing to the audience. We’re not even supposed to have characters names start with the same letter, much less the same name. What if we have one Darryl do something one week and the other do something else next week? How will people refer to them at the watercooler at work the next day, and how do we have the other characters refer to them? Do we label one Darryl one and the other Darryl two, or do we eventually call them one and two in some subtle homage to Dr. Suess? If we don’t do something like this, it will prove too confusing for the audience.”

“We keep the actors on the show for the sole purpose of this one joke,” one of the writers responded. “They don’t do anything themselves. They’re a trio, and Larry does all the talking for them, and he answers any and all questions for them.”

“It is kind of funny, in a taboo breaking, offbeat, and weird sort of way,” the head writer would respond, “but no family gives two of their sons the exact same name?” (George Foreman would later name all five of his sons George.)

“Like everything else, it could be funny,” another writer adds, “through repetition.”

In any song, TV show, or movie, we eventually learn the long-held secret behind lyrics, lines, and why things in the production were the way things were, but to my knowledge, based on some research, no one has broken ranks to tell the tale behind ‘Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darry, and this is my other brother Darryl’. The best explanation I’ve found is it just “became a recurring gag throughout the series”. The first time it happens, we’re kind of, ‘What did he just say? That’s odd.’ The second time through, we remember it from the first time, and then it builds and builds until it eventually catches on.

In any song, TV show, or movie, we eventually learn the long-held secret behind lyrics, lines, and why things in the production were the way things were, but to my knowledge, based on some research, no one has broken ranks to tell the tale behind ‘Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darry, and this is my other brother Darryl’. The best explanation I’ve found is it just “became a recurring gag throughout the series”. The first time it happens, we’re kind of, ‘What did he just say? That’s odd.’ The second time through, we remember it from the first time, and then it builds and builds until it eventually catches on.

We can only imagine that ‘Hi, I’m Larry, this is my brother Darry, and this is my other brother Darryl’ was a tough sell in the beginning. We have to imagine that it was not part of the original pitch of the show, and that it had to be a tough sell in subsequent production meetings. “We think it will be funny, eventually,” one of the writers probably said, early on, “and who knows how or why these things catch on, but we think this will eventually catch on.” We have to think that such a line required some big-time backing, “Besides, Bob [Newhart] loves it, and he wants it kept in.” We have to think it was not the make-or-break hill anyone on the production team were willing to die on. “We like it a lot, but we’re not married to the idea.” This is all speculation, of course, but the staff obviously did whatever they had to do to get the green light from the network.

Now imagine how shocked everyone involved in the early stages of the production was when this line eventually caught on. Imagine how shocked they are now, when these retrospective articles come out and this line, and the final episode, are the two things most people remember about their beloved series, thirty-plus-years later. The cast had to be shocked that it proved so popular, the writer who wrote the line was probably stunned, and the studio execs who surely offered notes that it was a dumb joke that would have to be clarified, were probably the most stunned of all. I was not a huge Newhart fan, but I watched it a lot. If there was ever an in-show explanation of the parents naming the two siblings Darryl, I never heard it, and if anyone on the production offered an explanation for this catchphrase, after the fact, I haven’t heard that either. My current searches, through all the venues offered today, turned up no explanation.

Whatever the case was, everyone I knew repeated this line, tried to use it in their own context, and they tried to further it in some sense, but even though we all greeted these references with a giggle, they never worked as well as it did on that show.

In the age of the internet, talk shows, podcasts, and DVDs with commentary added, we’ve grown accustomed to answers to every question we could possibly have. If Newhart were more popular, we might have that answer by now. If it carved out a niche in the zeitgeist, similar to Seinfeld, Frasier, or Friends we have to imagine that fans would badger the stars, creators, or writers for some kind of answer. There might be five-to-ten people who know the origin story, or some sort of backstory, but no one has badgered them for it. My best guess is if the story behind the recurring gag was half as funny as the line, somewhat interesting, or it hinted at the creativity of the originator, we’d all know it by now. The backstory is probably one of the best examples of how the explanation of a joke is almost never as funny as the actual joke, so you take a step back and leave it as a standalone.

The actual explanation probably involves the fact that one of the writers knew a family that gave two brothers the exact same name, a family name that was given to the siblings as an homage to another family member, but to avoid confusion they addressed ‘the other brother’ with a nickname. Whatever the case is, the writers probably considered the origin story so unfunny that it undercut the perceived brilliance of the idea so much that they decided to never tell it. I searched through search engines, Bing’s Co-Pilot, and I even left the open-ended question on a chat platform for anyone who might know how this recurring gag was born. I expected some internet searchers, or some huge fan who saw the commentary edition of the series to offer up some explanation they heard. So far, no takers. I was a little surprised to learn that it doesn’t matter how much research we do, in the Information Age, some of the times the truth is not out there, because some of the times, the arbiters of truth won’t give it up.