“I’m smart. Not like everyone says. I’m smart, and I want respect.” –Fredo from The Godfather. I love this quote, as anyone who has ever read this site knows. I use it so often that I use it so often, too often, because it just seems to be an evergreen quote that fits so many of my themes. It’s an everyman quote. It’s one of those quotes that if we don’t say it every day, we probably think it. We know we’re not able to figure some things out, but we’re able to figure out a mess of other things, so that should make us smart right?

What is smart, intelligent, or knowledgeable? It’s a question loaded with so many variables that it’s the literal definition of a loaded question. There are so many forms of human intelligence that it takes a lot of intelligence to understand the definition of intelligence. We all have some figurative schemes of thought that we use to develop images for matters of discussion. If I were to ask you what the elite intellectual looks like, you automatically picture the white lab coat. Researchers conducting tests on individuals know that if they want their subjects to take them seriously, they need to have a closet full of white coats. Ear, nose and throat, family practitioners probably also have a closet full of white coats they wear to presumably put an end to us complaining that they don’t know what they’re talking about. Depending on their goal of leading us to assume they’re smart, they might also want to mess their hair up (a la Albert Einstein), exhibit poor social skills, and thet should probably look like he doesn’t spend enough time outside. Our local car mechanic doesn’t fit any of these bullet points, however, but if you’ve ever sat down with one of them, you know the best and brightest among them have such a wide array of intelligence of their profession that it can be humbling and disorienting to hear them go on. That’s pretty relative you might argue, because we all have our areas. That’s kind of the point though isn’t it? If a man in a lab coat has a spark plug go out in his engine, he’s as lost as the rest of us, and the epitome of relative definition of intelligence. We all have our areas that make us feel smarter than most, but we eventually run across something, someone, or some other person place, place, or thing that makes us feel pretty darn dumb.

What is smart, intelligent, or knowledgeable? It’s a question loaded with so many variables that it’s the literal definition of a loaded question. There are so many forms of human intelligence that it takes a lot of intelligence to understand the definition of intelligence. We all have some figurative schemes of thought that we use to develop images for matters of discussion. If I were to ask you what the elite intellectual looks like, you automatically picture the white lab coat. Researchers conducting tests on individuals know that if they want their subjects to take them seriously, they need to have a closet full of white coats. Ear, nose and throat, family practitioners probably also have a closet full of white coats they wear to presumably put an end to us complaining that they don’t know what they’re talking about. Depending on their goal of leading us to assume they’re smart, they might also want to mess their hair up (a la Albert Einstein), exhibit poor social skills, and thet should probably look like he doesn’t spend enough time outside. Our local car mechanic doesn’t fit any of these bullet points, however, but if you’ve ever sat down with one of them, you know the best and brightest among them have such a wide array of intelligence of their profession that it can be humbling and disorienting to hear them go on. That’s pretty relative you might argue, because we all have our areas. That’s kind of the point though isn’t it? If a man in a lab coat has a spark plug go out in his engine, he’s as lost as the rest of us, and the epitome of relative definition of intelligence. We all have our areas that make us feel smarter than most, but we eventually run across something, someone, or some other person place, place, or thing that makes us feel pretty darn dumb.

Some of the smartest people I’ve ever met also had another key ingredient that is in short supply: clarity. They not only have a clearer vision of life than the rest of us, they have wisdom based on experience. They’re not afraid, intimidated, or confused by questions, arguments, or refutation. They’re able to roll with the punches, because they’ve already argued with so many people that they know every possible argument for and against. Yet, before we consider those with greater clarity intelligent, we have to consider another variable of intelligence: sensitivity. Most clear-minded people I know suffer from some deficits in emotional intelligence. They know the truth as they’ve experienced it and seen it, but they don’t account for all of the variables that could undermine their version of the truth. Can something be true, if it is only true 99.9 percent of the time? If an emotionally intelligent percent invites anecdotal evidence that undermines that truth, is it still true? There are times when it seems clarity and sensitivity seem to be combatants in the pursuit of truth, intelligence, and knowledge. Most clear thinkers are so lacking in sensitivity that they almost seem robotic, and they view arguments against their views as an attempt to cloud the truth and add confusion, but they don’t alter their views one iota.

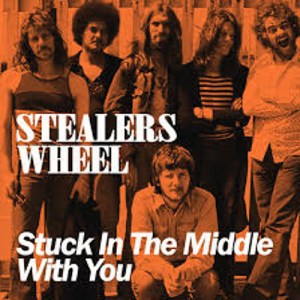

The more succinct definition of intelligence is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge. That definition might lead us to seek all of the varying definitions of knowledge, and how we apply it. It doesn’t serve a purpose, but some of us have retained more knowledge about the NFL, from the 80s and 90s, than most of the experts on pregame, NFL shows. Try to stump us. Go! Some of us know more about the show Seinfeld than anyone we’ve ever met. Say what you want about such knowledge, but it is information that we’ve retained, and in some cases used, or applied, as we’ve dropped the show’s jokes in a timely manner that has impressed people. Is it smart though? Will our audiences consider that intelligent? Our friends probably consider retention of such information the definition of intelligence, but how many strangers, who didn’t grow up in the same era we did, will put that information/knowledge on the same level with the man who is intimately familiar with Shakespeare or Chaucer? If you’re anything like me, and you enjoy searching for seemingly impossible answers to questions, you’ll probably end up saying, “I honestly don’t know if I’m smart or dumb. I’m probably Stuck in the Middle with You.”

The more succinct definition of intelligence is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge. That definition might lead us to seek all of the varying definitions of knowledge, and how we apply it. It doesn’t serve a purpose, but some of us have retained more knowledge about the NFL, from the 80s and 90s, than most of the experts on pregame, NFL shows. Try to stump us. Go! Some of us know more about the show Seinfeld than anyone we’ve ever met. Say what you want about such knowledge, but it is information that we’ve retained, and in some cases used, or applied, as we’ve dropped the show’s jokes in a timely manner that has impressed people. Is it smart though? Will our audiences consider that intelligent? Our friends probably consider retention of such information the definition of intelligence, but how many strangers, who didn’t grow up in the same era we did, will put that information/knowledge on the same level with the man who is intimately familiar with Shakespeare or Chaucer? If you’re anything like me, and you enjoy searching for seemingly impossible answers to questions, you’ll probably end up saying, “I honestly don’t know if I’m smart or dumb. I’m probably Stuck in the Middle with You.”

“Clowns to the left of me

Jokers to the right

Here I am stuck in the middle with you

When you started off with nothing

And you’re proud that you’re a self-made man.” –Gerry Rafferty and Joe Egan

I’ve met a wide array of writers throughout my life. Some of them exposed for me the difference between the creative term brilliance and the more math and science definition of intelligence. I’ve met brilliantly creative writers who were so good that I was just plain jealous, which led me to try to outdo them with a long stretch of writing. I’ve also met a number of writers who knew the craft so well that they gave me some excellent pointers and valuable information that I still have in my head whenever I write. They knew the ABCs of writing so well that it was a little surprising to learn they were actually average-to-poor writers. When I see them now, I call them editors. Editors can spot all of the errors of the creatives, and their approach to writing can be so oriented in fact that it takes all the fun out of writing. Most of them don’t do it to be mean, better, or correct, it’s just the way their mind works. They’ve learned the craft by studying the masters, and if we run into a wall, they can provide helpful advice based on their studies. There’s nothing wrong with that of course, but most of them don’t know their limitations. It seems to me that they know masters’ masterpieces, so well that they wouldn’t dare approach the craft in an innovative manner that might violate the tenants laid down by those they deify. They know the masterpieces far better than jokers to the right, and they’re paralyzed by idea that if they can’t top them, why try? Those of us who aren’t as familiar with the literary canon might be dumb enough to think we have something to add to the conversation. Even if we don’t come anywhere close to what editors determine to be quality material, we don’t lie awake at night in fear of a clown from the right dropping the dreaded ‘D’ word, derivative, on us.

Those of us stuck in the middle with you grew up on KISS, and heavy metal, and we loved the silly, simplistic movies and shows from the 80s and 90s that knew how to get to the point. If we were to ask members of that generation (my generation) I suspect that most of them would say, “It was a pointless era, but who cares, it was built on being fun, funny, and entertaining.” Whatever point these entertainers had, they got to it quick, because they feared belaboring a point might lose them their short-attention span, key demo. Those stuck in the middle with you have those influences loaded in our neurons, firing our synapses. Is that a brag? Some of the songs, shows, and movies from that era were quite innovative, creative, and influential, but no one would confuse memorizing the lines of dialogue from Buggs Buggy and Gilligan, or studying the lyrics of KISS, with an intellectual exercise. Yet, when we combine all of that silly simplicity with an appreciation for the masters of literature, we end up somewhere in the middle.

Those of us in the middle “Started off with nothing”. The “Theys” of our lives helped us form a foundation by teaching us the elements of style, and the rules, but they couldn’t teach us how to deviate. Those deviations defined us in many ways, ways that led us to be a self-made man when it came to writing. We normally equate the term self-made man with success, but the self-made men who ended up anonymous failures are far more numerous. They just didn’t succeed. They were the dreamers who were so delusional they never paid heed to those who told them to give up, because they were making fools out of themselves. The term self-made man is a nebulous one that we could apply to high school graduates and “some college” applicants. We could apply it to artists, craftsmen, and small business owners who had to claw and scratch their way to some relative definition of success. The opposite of self-made man, arguably and debatably, is the college graduate. The college graduate is the product of at least four years of shaping and molding, until he establishes himself in the workplace or office.

We could also say that the difference between the self-taught, or autodidactic, and the college graduate, or manualdidactic(!), is status. The mindset of the college graduate is that they’ve achieved status, and the self-made man is forever in pursuit of it. If we think about this dynamic in terms of the waiting room for a job interview, the college graduate believes he completed most of the interview on his resume, as he listed out the bullet points of what he did in college. He has achieved knowledgeable status, and he thinks the interview process will be paint-by-numbers after that. The high school graduate and “some college” applicant sits with inferiority complex believing that everyone else in the waiting room is a college graduate. His need to prove himself surely preceded his entrance into the building, as he apprenticed for the job doing grunt work in the field in question. Who will the head hunter in Human Resources view as more intelligent, knowledgeable, and the better candidate in the interview? It’s all relative to the head hunter, of course, but self-taught man knows that the onus will be on him to prove himself in the interview.

When we hear the self-made man talk about his pursuit of success, we often hear them make the dubious claim that, “Everyone was against me,” and/or “Nobody thought I would succeed,” but we could argue that such lines romanticize their struggle. More often than not, no one cared about them when they weren’t doing anything, because why would they? If they cared at one time, it probably took the self-made man so long to get there that everyone just sort of gave up on them. The self-made man probably had a lot of people cheering him on in the beginning, and that probably ignited something in him, but whereas they started giving up on him, he never stopped believing. The self-made man probably thought there was something to it, even when there wasn’t. Whatever stoked his desire to believe in himself took, and he continued to believe in himself regardless. Most of us don’t even remember the initial driver that spurred us onto further creations, but there is some inner drive to keep doing it. We’re the self-made, self-taught men who spend our time striving to prove that we’re not as dumb as our college transcripts suggest, and we are endlessly pursuing the sometimes-silly things we love with passionate zeal.

In the craft of writing, over-the-top intellectuals are also handicapped by the Great-American-Novel syndrome. They can’t write anything that is anything less than the most important thing ever written. This is probably why they sit behind a blinking cursor for so many hours. They are profound thinkers who refuse to write anything common (“Don’t be common!”), trite, cliché, hackneyed, or banal. They prefer to dazzle with the unfathomably amazing, the intellectually illuminating, and that which is illustrative of the plight of mankind against the meaning of life. “Just write,” writing experts tell us. “I can’t,” they say. “I can’t think of anything.” They usually sit before those blinking cursors trying to come up with something so brilliant that it’s beyond brilliant. Then, in those writing groups, they criticize those who produce the common, trite, cliché, hackneyed, or banal, until they realize they share more characteristics with editors than they do writers. Those stuck in the middle with you don’t know what we don’t know, and we’re just dumb enough to think we might have something so entertaining we might eventually add a nugget that is enlightening.

“Get in, get pithy, and get out,” are the words we employ.

When we’re stuck in the middle with a quality author we get this sense that we’re joining hands with them as we walk with them on their path of discovery. If they do it right, it won’t be limited to just a facts based adventure. The quality author is still intimately familiar with being dumb on the issue, and we can hear the joy in their voice as they discover all this great knowledge. They know that fuzzy line between intellectual and dumb so well that they know how to tap dance on both sides, and we laugh right along with him. As much as we prefer to think we get it, whatever it is, we actually don’t most of the times, because we’re not as smart as those who do. We do enjoy the pursuit of knowledge, but we don’t enjoy hearing some professorial presentation from someone who knows the facts so well that they are all but reading them on a Teleprompter. Those of us stuck in the middle with you, on that fuzzy line between intelligent and dumb, are not so far removed from our misunderstandings of the world that we don’t take them for granted and no longer question the ways of the world anymore.