Have you ever heard someone say something so weird it shocked you? Have you ever heard someone say something that you thought not even a weird person would say? They might think it, but they wouldn’t say it. They’d fear everyone knowing how weird they were.

“Doesn’t, he have cable?” someone asked in the aftermath of the shocking statement. We laughed. We all laughed, hard. We laughed because that line captured what we were all thinking. We had cable TV, and it shaped and molded our expectations of one another. We unconsciously expected everyone to know their station, and if one of us was unable to maintain a level of sameness, we expected them to conceal it beneath layers of shame and fear. Xavier McVie didn’t appear to care about any of that.

“He is not weird,” someone responded with some accusation in her voice. “He just says weird stuff.” She wasn’t  defending Xavier. She didn’t like Xavier, so we knew she wasn’t defending him. She was implying that ‘he wishes he was weird, but he’s not’. Why would anyone wish they were weird, we wondered. There was something to it we knew, because Xavier seemed normal most of the time, but he’d drop these thoughts on us so often that her characterization of Xavier McVie seemed to be a decent category for him.

defending Xavier. She didn’t like Xavier, so we knew she wasn’t defending him. She was implying that ‘he wishes he was weird, but he’s not’. Why would anyone wish they were weird, we wondered. There was something to it we knew, because Xavier seemed normal most of the time, but he’d drop these thoughts on us so often that her characterization of Xavier McVie seemed to be a decent category for him.

Some say that the need to label, categorize, or judge our peers is wrong, but it’s kind of what we do. Our brain is the primary weapon we have against powers foreign and domestic. It’s what separates us from the rest of the animals, and we use judgment to enhance our quality of life and in some cases our survival. If a lion slaughters a gazelle in an unorthodox manner, other lions might take note, but it doesn’t affect their perception of that lion. They don’t care how another lion takes a gazelle down. They just want to eat. Humans, on the other hand, care very much when, where, and why our fellow humans act the way they do. We want to know who to befriend, how to befriend, and if we should avoid certain people for our own self-preservation.

Anyone who knows someone who is handicapped knows that most of us avoid them as if their ailment is contagious. We might sympathize with their plight in life, but we don’t want to be around them. We prevent our children from staring or asking questions, and we move away swiftly. We do the same with those we consider weird. “He’s just weird,” we say to explain why we avoid them. “He’s just too weird.” Why do we avoid the weird? Why do we tell others to avoid them? When they introduce weird ideas to us, we don’t want to know how they arrived at that idea. We don’t want to discuss their novel approach to living. We shield our children from them and move away swiftly. We think we have a certain hold on reality, and human nature, and anyone who introduces us to the depths of their experience provides us an outlook that if we stare too long at it, it might start looking back at us.

Most truly bent people don’t want to do this to us anymore than they want to do it to themselves. They don’t want people to avoid them. They strive to fit into our longitudes and latitudes and platitudes, but some don’t. Some don’t care what we think, and when it’s a punk ethos we respect it. When it doesn’t have anything to do with a militant need to shatter our illusions and delusions, we’re confused. We don’t know how to put our finger on it. We need something to help us understand. We develop something, such as a dartboard as a visual display, to explain it, so we don’t have to yawn our way through theoretical exposition.

The center of this dartboard, the bull’s eye area, is absolute normalcy. For all that Xavier McVie said, we knew he was normal, so we placed him between the triple score area and the bull’s eye. Russell Hannon’s eccentricities, on the other hand, were more organic, and his efforts were geared toward being considered normal by the rest of us. This placed him between the triple score area and the outer reaches of the dartboard where the double score area lies. In each of the little boxes on the dartboard, we listed some of the characteristics that defined the individuals we attempted to categorize. Why are some people slightly off the trail? Some have minor brain malfunctions, others have brain chemical deficiencies in certain areas, and still others have such unusual upbringings that they accept certain other norms as truths. The rest of the little boxes contained a description of a different characteristic that leads to unusual thinking.

Another instrumental characteristic of the visual display the dartboard provides are the borders that divide the various rings and boxes. These borders not only helped us define normal vs. the abnormal, but they illustrate the obstacles an abnormal person must pass to achieve a more normal perception. Abnormal people know these borders well, and they’ve spent most of their life trying to overcome them. They’ve had unusual, strange, and absurd thoughts their whole life, and it takes some effort on their part to keep them unknown. They know that saying such things aloud might serve to reinforce their borders, so they learn to just stop saying them. To attempt to eviscerate the dartboard borders before them, they also exaggerate the normal characteristics they’ve learned by watching other, more normal people. Their goal, of course, is the middle of the dartboard, an arbitrary and relative definition of absolute normal, and to near it they begin to act hyper-normal.

Normal is a relative term, of course, and it invites all sorts of questions about what is normal and abnormal. Defenders will suggest there is no such thing as absolute normal, as there are no absolutes. It’s a valid argument when it comes to characteristics, but for the purpose of this exercise let’s say that, at least by comparison, we’re normal.

The normal often seek anything but. We enjoy weird music, sayings, conclusions, and anything else that is weird excites us because it is different from everything normal. “Normal is boring,” we shout out to the spectators who wish they were half as normal as us. We don’t understand the plight of the abnormal, and we take our normalcy for granted. We want to escape what we consider its confining borders.

The abnormal avoid anything weird, and they avoid it like the plague, which to them it almost is. It’s a mindset that has chased them throughout their lives. They seek an antidote in others. They watch us and imitate us, hoping that the rest of the world might consume them and confuse them with us, the more normal. They take our characteristics, the characteristics of their other friends and family, and the characteristics of that guy they ran into at the bar who seemed so normal that they almost envied him, and they stir them in a big pot and exaggerate them to display characteristics we might call hyper-normal, so someone, somewhere might accidentally confuse them with normal.

Those of us who are fascinated by the borders between normal and abnormal among our peers don’t search for these characteristics. Our default thought is that everyone is at least as normal as we are, until we learn otherwise. The effort to achieve hyper-normal characteristics are often less than organic, however, and they have a way of eventually betraying their host when they least expect it.

We all love music, and we use it as a barometer to gauge those around us. We use it to define who is cool and nerdy or hip and old-fashioned. We might think this is relegated to high school, but in many ways, we never leave high school.

Our initial inclination might be that weird people love weird music, but here’s where the norms seeking the weird and vice versa come into play. This is where normal people say, “Normal is boring!” to escape their border. Weird music satisfies their temporary aesthetic need for contrast. Those on the outside looking in, listen to more normal music with hope. By listening to normal music with normal lyrics that deal with normal hopes, they hope to keep strange and weird ideas out of their heads, because they’ve made so much progress toward the center that they don’t want to risk taking a step back, even if it is only in the arena of impressions. The music they enjoy is so normal that one might define it as hyper-normal. What is normal music? There’s no definitive answer of course, but if more people are listening to a certain kind of music doesn’t that make it more normal? It might not to you and I, but what does it mean to a person hoping to leave a more normal impression?

The abnormal might consult Billboard charts or a listing of downloads. “Think about it, how many people listen to your favorite artist?” they might ask. “How many people listen to mine? Who’s the freak now?” The favored artist of the abnormal sell millions of albums and millions downloads. “That artist is my favorite, and I’m going to tell the world about it.” They don’t want to listen to weird music, but they also don’t want us to know they listened to it, because they fear someone, somewhere might think they enjoyed it.

Those of us who competed with one another to find weird music grew up listening to the staples, and we eventually grew bored with them. We went through all the phases, perpetually seeking something different, until we arrived at the most unusual music you’ve probably ever heard.

Most of those outside our tight circle of music aficionados did not enjoy the music we shared with them. They said they didn’t get it, and some of them said it was just too weird. “This is what you’re listening to?” they said with some disdain. Their rejections were mostly fun, polite, and the good-natured type of ribbing that says, “I don’t know how normal you can be listening to that. That ain’t normal.”

Russell Hannon’s reaction to our music was not fun or polite. His reaction was so over-the-top obnoxious that he left us all silently staring at him, then one another in its aftermath. Did he just accidentally reveal everything he spent years concealing from us? We didn’t know at the time. At the time, we were left with ‘What was that?’ expressions on our faces. It was one of those type of reactions that everyone uses to connect all the various dots they saw before and after the reaction to form some sort of impression.

“That’s the weirdest [stuff] I’ve ever heard,” he said so loud that we couldn’t help but look around to see who he was screaming at. “How can you listen to [stuff] like that?” Later, when others agreed to listen to our music, he privately warned them to avoid actually playing it in their disc player. “It’s just so weird. You’ll hate it.“

“Why didn’t you just say you don’t care for my music?” we said in the aftermath of all that. “Why did you have to make such a show of it?”

He said some stuff that we can’t remember, but our initial inclination was to view his obnoxious rejection of our music as a personal condemnation, and that he wanted to make defamatory statements about us that he wanted our co-workers to echo. What we didn’t understand at the time was that it had less to do with the music or his preferences and more to do with his intent to use our music as a platform to inform those in our world that he was so many levels closer to normal than we were. He wanted to stand atop us in this world of perceptions and declare that he would never deign to listen to our weird music ever again, and they shouldn’t either. That music, he said through actions not words, is not for we normal folk.

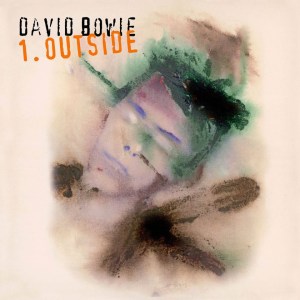

As a result, when Xavier McVie joined our team, we were a little sheepish about lending our music to him. Especially after he and Russell Hannon made something of a connection. We expected Xavier to reject our music in the same vein Russell did. When Xavier didn’t just enjoy our music, but he tried to top it, it surprised us all. He would lend us equally strange music that he considered better. We knew music as a barometer of cool and uncool, but we never considered it an indicator of the various levels of sanity. We still didn’t consider it a comprehensive reflection on Russell’s sanity, but it was a dot in a landscape of dots that informed us Russell’s hold on sanity was a lot more tentative than any of us suspected. If a truly weird person was off the cliff, in other words, Russell Hannon was clinging to the edge screaming for us to help him before he falls. We didn’t know where Xavier McVie was in this analogy, when he not only embraced our music but tried to top it with weirder music, but we thought he might have an unusually unusual mind.

***

We met a number of unusual thinkers before and after Xavier McVie. When we met them, we were so fascinated and excited that we developed a bad habit of interrogating them. “Why did you do that?” we would ask some, and “Why do you think that?” we would ask others. These initial Q&A’s were friendly and polite, but our innate curiosity drove us to ask questions beyond the why to the how. How did you arrive at that line of thought, and most of the insecure didn’t react well to this line of questioning.

“I’m sorry, but your line of thinking is just so unusual that I want to know everything I can about it,” we said. Most of them were still insulted that we would insinuate that they were, in any way, weird.

“You think I’m weird? What about you?” they asked.

Until we could establish our genuine curiosity, most people were combative.

In the face of our unusual brand of polite, patient interrogation, some unusual thinkers begin to wilt and eventually become insulted. Most people don’t see anything wrong with their thought processes, as it’s the only thing they’ve ever known. Some, very few, became as intrigued with their thought process as we were.

When we found the few willing participants we did, over decades of this casual intrigue, we found that it often takes unusual thinkers a long time to find the source their unusual thoughts, if they ever do. The one thing in our favor is that most people love to talk about themselves, even if they don’t consider themselves as weird, strange, and just plain different as we do.

Of those who responded well to our questions about the source of their unusual thinking, some suggested that a break might have occurred as a result of an incident. Two of them cited a traumatic episode in their life that they considered so shocking that it might’ve changed their way of thinking. One was a shockingly horrific car accident, and the other suggested it might be the premature death of a loved one who guided them philosophically in life. Most of the people who agreed that they had an unusual take on life, and that it might be based on some experience in life, had a more difficult time arriving at a source than Xavier did. Xavier was quick with it, though he was as suspicious about it as we were.

“I don’t think I had some psychological break or bend away from the norm, as you put it,” Xavier McVie said. “If I did, I think it might’ve had something to do with a young girl enticing me to try some LSD when I was far too young and not equipped to handle it. She was a teenage girl. Her name was Mary, and when she offered it to me, and two other guys, I was barely a teen myself. I was the only one of us with the courage,” and he said that with air quotes, “and I now say stupidity, to take it. Mary was an older girl. She was probably two years older, but she had all the things boys like. I thought a lot was on the line when she offered it to me. I thought it might change the course of our friendship, in ways a teenage boy hopes to advance their friendship with girls. When I took it, it changed me. I know it goes against the science on we have on drugs, but I swear the reaction I had lasted years. The way I see it, I was a normal, happy boy on a Thursday, and on Friday I was an angry teenager who felt so abnormal that I hated myself.

“Some called it a bad trip,” Xavier continued. “I hated those two words for years. You don’t understand, I would say. I’ve read a lot about reactions to controlled substances since then, and I’ve read that reactions are so varied that there is no consensus on how people will react. The brain is so different that some say it’s almost impossible to know how someone will react. Some are more susceptible to bad trips than others are. It took about twenty minutes for the LSD to really hit, but when it did I went through a lot. I went through every horrible experience I had in life in real time, and when I say real time, I mean real time. I relived the experiences as if I was going through them all over again. ‘That’s the definition of a bad trip,’ they said as if I should just say, “Oh!” and move on in life. “You don’t understand,” I told one of the people who said that, “I came out of that experience different.”

“My mom even noticed it,” Xavier continued. “She said, ‘What is wrong with you these days. You used to be such a happy boy.’ She thought it was the teen years, or some after-effects from my dad’s death. She sent me to a psychiatrist and all that, but it didn’t help. I never told my mom or the psychiatrist about the LSD. I probably should’ve, but it scared me so much that I wanted to put it behind me, as if it never happened. It might’ve been the dad thing, the teenager thing, or all of those things, but that experiment with LSD changed me so much in such a short time frame that I think I came out of it different. I relived so much, and experienced such nasty effects on that drug that it scared me.”

Three other willing participants of our polite interrogation cited an experience with drugs, similar to Xavier’s except one suggested it was the morphine a doctor prescribed and the other suggested she had a “bad reaction” to the lidocaine a dentist used before a dental procedure. The last one we talked to before he met Xavier, cited a shocking moment when an authority figure betrayed their relationship with them in a life-altering way.

As we wrote, most of those we grilled in polite, casual, and lengthy Q&A’s didn’t think there was anything wrong with them. Most of those who agreed that they were unusual thinkers didn’t think there was ever an incident or episode that drove them to think different, but some of those who did eventually arrived at an answer. Whether or not it was the answer is debatable, of course, but they thought they had an answer. The idea that these people exaggerated the effect these episodes had on them is probable, as it’s difficult to imagine that one incident, no matter how horrific or traumatic, can change a person so completely, but they thought it did. The first question we asked ourselves was, what if it didn’t? What if they exaggerated their reaction to an incident, an episode, or a drug, for an answer? The question we ask ourselves now, looking back on all of these Q&A’s is, is it better and healthier for an Xavier McVie to have an answer regarding his break from reality, even if it’s not 100% accurate? Should we have informed him that his suspicions were correct and that the myth about a 20-year flashback is just that, a myth. Russell Hannon, would’ve never sat down for a Q&A. He was so convinced he was the absolute center of normalcy, the bull’s eye of normalcy, that it would’ve been pointless to even ask him about his mindset. Russell and Xavier were both unusual thinkers, but does Xavier have a better chance at maintaining a relative level of normalcy, because he lists an incident that led him to some bend in his way of thinking? Even if it could be proven untrue? Is it better for him to have answer to explain it, because if he knows the trail from, it might put him back on the path back to.