We envy those who knew, at a relatively young age, what they wanted to do for a living. We may have experienced some inspirations along the way, but we either lost interest quickly, or we never follow through. Whatever the case was, no one I know read medical journals, law reviews, or business periodicals in our formative years. We preferred reading the latest NFL preview guide, a teenage heartthrob magazine, or one of the many other periodicals that offer soft entertainment value. Most of us opted out of reading altogether and chose to play something that involved a ball. Life was all about fun for the kids in our block, but there were other, more serious kids, who we wouldn’t meet until we were older. They may not have known they would become neurosurgeons, but they were so interested in medicine that they devoted huge chunks of their young lives to learning everything their young minds could retain. “How is that even possible?” we ask. How are they able to achieve that level of focus when they were so young? Are we even the same species?

At an age when we’re so unfocused, some claim to have had tunnel vision. “I didn’t have that level of focus,” some said to correct the record, “not the level of focus to which you are alluding.” They might have diverged from the central focus, but they had more direction than anyone we knew, and that direction put them on the path of doing what they ended up doing, even if it wasn’t as specific as we might guess.

The questions regarding what we should do for a living has plagued so many for so long that comedian Paula Poundstone captured it with a well-placed joke, and I apologize, in advance, for the creative paraphrasing: “Didn’t you hate it when your relatives asked what you wanted to do for a living? Um, Grandpa I’m 5. I haven’t fully grasped the importance of brushing my teeth yet. Now that I’m forty, I’ve finally figured out why they asked that question,” Paula Poundstone added with a comedic pause. “They were looking for ideas.”

The questions regarding what we should do for a living has plagued so many for so long that comedian Paula Poundstone captured it with a well-placed joke, and I apologize, in advance, for the creative paraphrasing: “Didn’t you hate it when your relatives asked what you wanted to do for a living? Um, Grandpa I’m 5. I haven’t fully grasped the importance of brushing my teeth yet. Now that I’m forty, I’ve finally figured out why they asked that question,” Paula Poundstone added with a comedic pause. “They were looking for ideas.”

Pour through the annals of great men and women of history, and you’ll find that some of the greatest minds of science didn’t accomplish much of anything until late in life. Your research will also show that most of the figures who achieved success in life were just as dumb and carefree as children as the rest of us, until something clicked. Some failed more than once in their initial pursuits, until they discovered something something that flipped a switch.

Even those who know nothing about psychology, know the name Sigmund Freud. Those who know a little about Freud know his unique theories about the human mind and human development. Those who know anything about his psychosexual theory know we are all repressed sexual beings plagued with unconscious desires to have relations with some mythical Greek king’s mother. What we might not know, because we consider it ancillary to his greater works, is that some of his theories might have originated from Freud’s pursuit of the Holy Grail of nineteenth-century science, the elusive eel testicles.

Although some annals state that an Italian scientist named Carlo Mondini discovered eel testicles in 1777, other periodicals state that the search continued up to and beyond the search of an obscure 19-year-old Austrian’s in 1876.[1] Other research states that the heralded Aristotle conducted his own research on the eel, and his studies resulted in postulations that stated either that the beings came from the “guts of wet soil”, or that they were born “of nothing”.[2] One could guess that these answers resulted from great frustration, since Aristotle was so patient with his deductions in other areas. On the other hand, he also purported that maggots were born organically from a slab of meat. “Others, who conducted their own research, swore that eels were bred of mud, of bodies decaying in the water. One learned bishop informed the Royal Society that eels slithered from the thatched roofs of cottages; Izaak Walton, in The Compleat Angler, reckoned they sprang from the ‘action of sunlight on dewdrops’.”

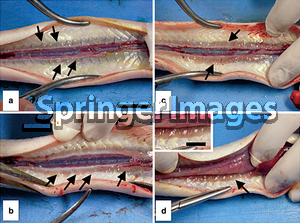

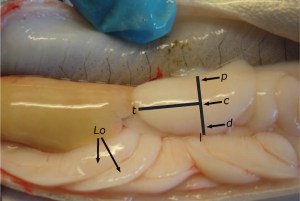

Before laughing at these findings, we should consider the limited resources those researchers had at their disposal. As is oft said with young people, the young Freud did not know enough to know how futile the task would be when a nondescript Austrian zoological research station employed him. It was his first real job, he was 19, and it was 1876. He dissected approximately 400 eels, over a period of four weeks, “Amid stench and slime for long hours” the New York Times wrote to describe Freud’s working conditions. [3] His ambitious goal was to write a breakthrough research paper on an animal’s mating habits, one that had confounded science for centuries. Conceivably, a more seasoned scientist might have considered the task futile much earlier in the process, but an ambitious, young 19-year-old, looking to make a name for himself, was willing to spend long hours slicing and dicing eels, hoping to achieve an answer no one could disprove.

Unfortunate for the young Freud, but perhaps fortunate for the field of psychology, we now know that eels don’t have testicles until they need them. The products of Freud’s studies must not have needed them at the time he studied them, for Freud ended up writing that his total supply of eels were “of the fairer sex.” Some have said Freud correctly predicted where the testicles should be and that he argued that the eels he received were not mature eels. Freud’s experiments resulted in a failure to find the testicles, and he moved into other areas as a result. What kind of effect did this failure have on Freud, professionally and otherwise?

Unfortunate for the young Freud, but perhaps fortunate for the field of psychology, we now know that eels don’t have testicles until they need them. The products of Freud’s studies must not have needed them at the time he studied them, for Freud ended up writing that his total supply of eels were “of the fairer sex.” Some have said Freud correctly predicted where the testicles should be and that he argued that the eels he received were not mature eels. Freud’s experiments resulted in a failure to find the testicles, and he moved into other areas as a result. What kind of effect did this failure have on Freud, professionally and otherwise?

In our teenage and young adult years, most of us had low-paying, manual labor jobs. We did these jobs to get paid when no one else would pay us. We bussed tables, took bags to hotel rooms, parked cars, and did whatever we had to to get paid. Our only goals in life were to do the job well enough to keep the boss off our back. We had no direction, and no one I know did what they did to end up in the annals of history. When we got fired or quit, we just moved onto the job that paid us more. We didn’t think about rewarding or fulfilling. We just knew we didn’t want to do that (whatever we did in the first job) anymore.

Was Freud’s search for eel testicles the equivalent of an entry-level job for him, or did he believe in the vocation so much that his failure devastated him? Did he slice the first 100 or so eels open and throw them aside with the belief that they were immature? Was there nothing but female eels around him, as he wrote, or was he beginning to see what plagued the other scientists for centuries, including the brilliant Aristotle? There had to be a moment, in other words, when Sigmund Freud realized that they couldn’t all be female. He had to know, at some point, that he was missing the same something that everyone else missed. He must have spent some sleepless nights struggling to come up with a different tactic. He might have lost his appetite at various points, and he may have shut out the world in his obsession to achieve infamy in marine biology. He sliced and diced over 400 after all. If even some of this is true, even if it only occupied his mind for four weeks of his life, we can imagine that the futile search for eel testicles affected Sigmund Freud in some manner.

If Freud Never Existed, Would There Be a Need to Create Him

Every person approaches a topic of study from a subjective angle. It’s human nature. The topic we are least objective about, say some, is ourselves. Some say that we are the central focus of speculation when we theorize about humanity. All theories are autobiographical, in other words, and we pursue such questions in an attempt to understand ourselves better. Bearing that in mind, what was the subjective angle from which Sigmund Freud approached his most famous theory on psychosexual development in humans? Did he bring objectivity to his patients? Could he have been more objective, or did Freud have a blind spot that led him to chase eel testicles throughout his career in the manner Don Quixote chased windmills?

After his failure, Sigmund Freud would switch his focus to a field of science that would later become psychology. Soon thereafter, patients sought his consultation. We know now that Freud viewed most people’s problems through a sexual lens, but was that lens tinted by the set of testicles he couldn’t find a lifetime ago? Did his inability to locate the eel’s reproductive organs prove so prominent in his studies that he saw them everywhere he went, in the manner that a rare car owner begins to see his car everywhere, soon after driving that new car off the lot? Some say that if this is how Freud conducted his sessions, he did so in an unconscious manner, and others might say that this could have been the basis for his theory on unconscious actions. How different would Freud’s theories on sexual development have been if he found the Holy Grail of science at the time? How different would his life have been? If Freud found fame as a marine biologist with his findings, he may have remained a marine biologist.

After his failure, Sigmund Freud would switch his focus to a field of science that would later become psychology. Soon thereafter, patients sought his consultation. We know now that Freud viewed most people’s problems through a sexual lens, but was that lens tinted by the set of testicles he couldn’t find a lifetime ago? Did his inability to locate the eel’s reproductive organs prove so prominent in his studies that he saw them everywhere he went, in the manner that a rare car owner begins to see his car everywhere, soon after driving that new car off the lot? Some say that if this is how Freud conducted his sessions, he did so in an unconscious manner, and others might say that this could have been the basis for his theory on unconscious actions. How different would Freud’s theories on sexual development have been if he found the Holy Grail of science at the time? How different would his life have been? If Freud found fame as a marine biologist with his findings, he may have remained a marine biologist.

How different would the field of psychology be today if Sigmund Freud remained a marine biologist? Alternatively, if he still made the switch to psychology after achieving fame in marine biology, for being the eel testicle spotter, would he have approached the study of the human development, and the human mind from a less subjective angle? Would his theory on psychosexual development have occurred to him at all? If it didn’t, is it such a fundamental truth that it would’ve occurred to someone else over time, even without Freud’s influence?

We can state, without fear of refutation, that Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual theory has sexualized our beliefs about human development, a theory others now consider disproved. How transcendental was that theory, and how much subjective interpretation was involved in it? How much of the subjective interpretation derived from his inability to find the eel testicle? Put another way, did Freud ever reach a point where he began overcompensating for that initial failure?

We can state, without fear of refutation, that Sigmund Freud’s psychosexual theory has sexualized our beliefs about human development, a theory others now consider disproved. How transcendental was that theory, and how much subjective interpretation was involved in it? How much of the subjective interpretation derived from his inability to find the eel testicle? Put another way, did Freud ever reach a point where he began overcompensating for that initial failure?

Whether it’s an interpretive extension, or a direct reading of Freud’s theory, modern scientific research theorizes that most men want some form of sexual experience with another man’s testicles. This theory, influenced by Freud’s theories, suggests that those who claim they don’t are lying in a latent manner, and the more a man says he doesn’t, the more repressed his homosexual desires are.

The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law, a sexual orientation law think tank, released a study in April 2011 that stated that 3.6 percent of males in the U.S. population are either openly gay or bisexual.[4] If these findings are anywhere close to correct, this leaves 96.4 percent who are, according to Freud’s theory, closeted homosexuals in some manner. Neither Freud nor anyone else has been able to put even a rough estimate on the percentage of heterosexuals who harbor unconscious, erotic inclinations toward members of the same sex, but the very idea that the theory has achieved worldwide fame leads some to believe there is some truth to it. Analysis of some psychological studies on this subject provides the quotes, “It is possible … Certain figures show that it would indicate … All findings can and should be evaluated by further research.” We don’t know in other words, there’s no conclusive data and all findings and figures are vague. Some would suggest that the facts and figures are so ambiguous that Freud’s theories were nothing more than a provocative and relatively educated and subjective guess.[5]

Some label Sigmund Freud as history’s most debunked doctor, but his influence on the field of psychology and on the ways society at large views human development and sexuality is indisputable. The greater question, as it pertains specific to Freud’s psychosexual theory, is was Freud a closet homosexual, or was his angle on psychological research affected by his initial failure to find eel testicles? To put it more succinct, which being’s testicles was Freud more obsessed with finding during his lifetime?

[1]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eel_life_history

[2]http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2010/oct/27/the-decline-of-the-eel

[3]http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/25/health/psychology/analyze-these.html

[4]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_sexual_orientation

[5]http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/assault/roots/freud.html