“When it comes to modern medicine, do you ever feel grateful?”

“I mean, yeah, but that’s like being grateful that Jupiter doesn’t fall off its axis. We know the catastrophe that would happen if it wasn’t there, but it’s always been there, so it’s tough to remain grateful for it.”

“Are you grateful for your good health?”

“Yeah, of course, but again, that’s like being grateful for good weather. We don’t notice it until the bad weather hits. We have to constantly have our perspective adjusted to appreciate health, wealth, and weather.”

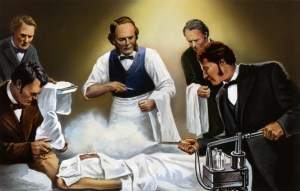

“Because after reading Thomas Morris’ The Mystery of The Exploding Teeth, I went real grateful that I didn’t end up in a different time. I know what you’re saying about it’s always been there, but damn, you read what those 19th Century doctors were doing to their patients back then, and it seems like they were just guessing most of the time.”

“Because after reading Thomas Morris’ The Mystery of The Exploding Teeth, I went real grateful that I didn’t end up in a different time. I know what you’re saying about it’s always been there, but damn, you read what those 19th Century doctors were doing to their patients back then, and it seems like they were just guessing most of the time.”

“Look, our moms took us to the doctor, and he fixed it. It’s what they do. I never considered myself ungrateful, or taking it for granted, but it’s their jobs.”

“Fair enough, but did you ever have something your doctor couldn’t fix? That’s some scary stuff, let me tell you. They put us through an array of tests, they prescribe stuff, just to see what works, “Take two of these and call me in the morning.” What if nothing your doctor tries works? Who do you blame? We don’t blame the researchers for failing to develop that perfect pharmaceutical to cure what ails us, we don’t blame innovators for failing to develop technological advancements necessary to find out what’s wrong with us, and we don’t blame modern medicine for being as yet ill-equipped or ill-informed to deal with our mysterious ailment. We blame our doctor. Our doctor is our hero or our zero, because they are our face of modern medicine. They’re who we see when we think of medicine. If you’re the one they can’t cure, it would be difficult for you to be grateful for the advancements of modern medicine, but the rest of should remember that for everything we can’t cure yet, the list of what we now can cure should earn a whole lot of gratitude. You’re right, it’s difficult to be grateful for good health, or life in general, but reading through a brief history of 19th Century medicine should remind us all to be grateful that we are not living in constant pain, and that our species managed to survive at all.”

Previous generations reminded us to remain grateful, “Always be grateful for the times you live in, because I’ve seen worse, and my parents saw far worse.” They don’t understand our technology, and the machines their doctors put them through overwhelm them. “Don’t take it for granted,” they say. The lead by example in this dictum, because they can’t believe they’re still alive, relatively healthy, and pain-free. No matter what they say or do, however, we were born with this technology, and we can’t help but take for granted what has always been there for us.

Author Thomas Morris might provide a better perspective for why we should be grateful, by “gently mocking” the medical practitioners of the 19th Century for their practices and procedures. Before gently mocking them, however, Morris adds two qualifiers every writer who compiles such material for a book should add before gently mocking prior eras for their lack of scientific knowledge:

“The methods they used were consistent with their understanding of how the body worked, and it is not their fault that medical knowledge has advanced considerably since then.”

It’s not their fault, I would add, and it’s wasn’t their doing. The doctors, family practitioners, or ear, nose, and throat specialists of the era were handcuffed by the constraints of knowledge at the time, and as Morris adds they performed admirably under such constraints.

“One thing that these case histories demonstrate is the admirably tenacious, even bloody-minded, determination of doctors to help their patients, in an age when their art left much to be desired.”

We could use the hindsight of modern medicine to call early 19th century medicine something of a guessing game, but will 23rd Century medical professionals think the same thing of 21st Century medicine? Western medicine has come a long way in 200 years, and Morris’ book emphasizes that, but professionals in various medical fields will admit Thomas Morris could write a second book called The 21st Century: What We Still Don’t Know. Modern authors probably won’t be able to write such a book, because they don’t know what they don’t know, but a Mental Floss article details some of basic, fundamentals we still don’t understand yet, including: why we cry, why we laugh, why we sleep, why we dream, why we itch, and how we age. These matters might seem insignificant in terms of greater physical health, but if we can unlock those mysteries, what answers might follow? As with modern medicine, The 19th Century medical professionals had precedent, studies, and literature to study and guide their decisions, but the precedents they followed, like ours, were as flawed as they were.

We could use the hindsight of modern medicine to call early 19th century medicine something of a guessing game, but will 23rd Century medical professionals think the same thing of 21st Century medicine? Western medicine has come a long way in 200 years, and Morris’ book emphasizes that, but professionals in various medical fields will admit Thomas Morris could write a second book called The 21st Century: What We Still Don’t Know. Modern authors probably won’t be able to write such a book, because they don’t know what they don’t know, but a Mental Floss article details some of basic, fundamentals we still don’t understand yet, including: why we cry, why we laugh, why we sleep, why we dream, why we itch, and how we age. These matters might seem insignificant in terms of greater physical health, but if we can unlock those mysteries, what answers might follow? As with modern medicine, The 19th Century medical professionals had precedent, studies, and literature to study and guide their decisions, but the precedents they followed, like ours, were as flawed as they were.

Thomas Morris, prefaces a quote from an article James Young Simpson, the pioneer of chloroform anesthesia, writing, “[Simpson] cautioned that it was unwise to be too hard on the “extravagance and oddity” of their methods, adding presciently:

“Perhaps, some century or two hence, our successors … will look back upon our present massive and clumsy doses of vegetable powders, bulky salts, nauseous decoctions, etc., with as much wonderment and surprise as we now look back upon the therapeutic means of our ancestors.”

Morris’ qualifiers illustrate how annoying it is to read modern authors assume a level of authority, even intellectual superiority, over the most brilliant minds of another era without qualifiers. These modern authors critique past knowledge and technology from the pedestal of modern research, acquired knowledge, and technology as if they had anything to do with any of it. Few of these authors acknowledge that they, like the rest of us, are the beneficiaries of modern advancements, even though they have not personally contributed anything to the difference between the eras.

That being said, we all know the line: “those who don’t learn from the past are condemned to repeat it.” There’s nothing wrong with mocking and ridiculing the past, because it makes the art of teaching history more entertaining, and we find mockery entertaining, but the author of it should provide some sort of context.

Thomas Morris pursuit of this is also admirable in another way, as it displays a takeaway, we can’t help but reach by the time we finish his book, gratitude. How many minor ailments (and there’s no such thing as minor when we’re suffering from them) can we magically resolve with two aspirin, ibuprofen, or a series of prescribed doses of antibiotics? How many procedures (currently considered routine) cure what harms us? How grateful are we to the technological innovators, doctors, and all of those who played roles (be they unwitting or otherwise) in the trial-and-error processes involved in research that have contributed to the progress medicine has made in such a relatively short time. It’s relatively difficult to be grateful for life, but as Morris’ book alludes, we should be grateful that our ancestors survived at all. We wouldn’t have the luxury of regarding our modern medicine as commonplace if they hadn’t, because as incredible as the human body is, it’s possible, and even probable, that we shouldn’t be here.

Thomas Morris pursuit of this is also admirable in another way, as it displays a takeaway, we can’t help but reach by the time we finish his book, gratitude. How many minor ailments (and there’s no such thing as minor when we’re suffering from them) can we magically resolve with two aspirin, ibuprofen, or a series of prescribed doses of antibiotics? How many procedures (currently considered routine) cure what harms us? How grateful are we to the technological innovators, doctors, and all of those who played roles (be they unwitting or otherwise) in the trial-and-error processes involved in research that have contributed to the progress medicine has made in such a relatively short time. It’s relatively difficult to be grateful for life, but as Morris’ book alludes, we should be grateful that our ancestors survived at all. We wouldn’t have the luxury of regarding our modern medicine as commonplace if they hadn’t, because as incredible as the human body is, it’s possible, and even probable, that we shouldn’t be here.

How did our ancestors survive the plague? World History Encyclopedia lists cures such as rubbing bare chicken butts on lesions, chopped up snakes, and drinking crushed unicorn horns as some of the more popular remedies at the time. They also list drinking crushed emeralds, arsenic, and mercury straight, with no chasers. How did we survive?

We currently believe in using cardiopulmonary resuscitation when a person stops breathing, but 19th century man believed, as Morris writes, that blowing tobacco smoke in someone’s rectum might revive them after, for example, a drowning. Other periodicals note that physicians played around with blowing smoke into the mouth and nose, but they found the rectal method more effective. “The nicotine in the tobacco was thought to stimulate the heart to beat stronger and faster, thus encouraging respiration. The smoke was also thought to warm the victim and dry out the person’s insides, removing excessive moisture.”

The “How did we survive?” head-shaking laughter the follows hearing such measures might cement the fact that no one ever tries to pass such foolish nonsense along again. While we’re laughing, however, let’s keep in mind how much information, innovation and technology benefits our definition of modern know-how. We could go through that list, but even if we bullet-pointed it, it would be so lengthy that our eyes might glaze over, and we might accidentally dismiss a most vital discovery, such as the germ theory.

How did we survive the years preceding someone’s idea that they might be able to scientifically confirm the idea that the onset and spread of disease might have something to do with microorganisms, pathogens, and germs. They suggested that eating spoiled food, drinking stagnant water and poorly preserved alcohol, among other things could cause disease and the spread thereof. Modern readers might “Of course!” such findings now, but it rocked the scientific community at the time. Although the records show that the idea that microorganisms might be the cause for the spread of disease dates back to ancient civilizations, the scientifically-backed idea was credited to Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch between 1860 to 1880, and that was probably made so late in the 19th century that we can guess that it wasn’t fully implemented by family doctors (AKA Ear, Nose, and Throat doctors, or ENT) until the early 20th century. Think about how many lives have been saved by the idea that stagnant water, spoiled food, and fermentation of wine could cause diseases. This first officially documented scientific discovery also paved the way for the first official, scientific discovery of the first, widely used antibiotic penicillin by an Alexander Fleming.

The ENT doctor is our face of modern medicine, much like the police are the face of law in our experience. They are the people we know, but if we think about it, the ENT doctor sits at the bottom of the medical community’s pyramid. They have nothing to do with the research that helps them make determinations on courses to follow or prescriptions to write. They follow the research and use the innovations created by others, so while we could say they are beneficiaries of modern medicine, future experts might say our modern physicians were captive to the limits of 21st century medical knowledge at the time.

Do we expect our ENT doctor to perform research in a lab before they diagnose us? Do we expect them to trial and error the medicine they prescribe? No, they have to act on the knowledge of those who specialize in those areas, and the 19th century ENT doctors and surgeons were no different.

Do we expect our ENT doctor to perform research in a lab before they diagnose us? Do we expect them to trial and error the medicine they prescribe? No, they have to act on the knowledge of those who specialize in those areas, and the 19th century ENT doctors and surgeons were no different.

How many modern patients enter a general practitioners’ office, see a specialist, and undergo the array of tests we currently have at our disposal, and we still don’t know what’s wrong with them? We hear it all the time, patient A entered the office with a condition that mystified the most brilliant minds of medicine who examined her, and she died before anyone could properly source her ailment. I’ve known such a situation personally, and I’ve witnessed it intimately. I only write that to suggest that my empathy goes out to victims, family members of victims, and anyone who know who has experienced such a matter, but there are times when no one is to blame. When we’re in such a desperate state, or grieving the loss of a loved one, our first inclination is to blame someone for not recognizing her ailment sooner. We blame her doctors, her doctors blamed the specialists, and they all quietly threw their hands up in the air in frustration. Who was at fault, or is anyone? Our advances in modern medicine, since the 19th Century have been so remarkable that they lead us to believe that we’re at the final frontier. We think if her parents could’ve only found the most brilliant mind of medicine, with all of latest technology available to them, and all of the information research has provided, we think she could’ve been cured. This isn’t to say there hasn’t been instances of malfeasance and misfeasance in the medical community, but some of the times we don’t know yet. That’s the harrowing, humbling truth that no self-respecting doctor, or anyone else in the medical field, will admit is that in some cases the science isn’t there yet.

If we were able to interrogate a family doctor, a surgeon, or someone else in the medical profession of 19th Century, I imagine a confident professional of that era might say, “Mock away, we deserve it on some level for our lack of knowledge, but you cannot say it was for a lack of trying. We cared deeply what happened to our patients, from the little, old ladies who complained about chronic ailments to devastated small boys and everyone in between. These were not only our patients, they were our neighbors, and members of our community seeking our knowledge, guidance, and medical assistance to relieve them of horrific illnesses and injuries, and we did our best, with our era’s best knowledge, technological advancements and research, to help them in every single way we could. It’s not what you have today, so mock us all you want, but you cannot say we weren’t trying.”

If we were able to interrogate a family doctor, a surgeon, or someone else in the medical profession of 19th Century, I imagine a confident professional of that era might say, “Mock away, we deserve it on some level for our lack of knowledge, but you cannot say it was for a lack of trying. We cared deeply what happened to our patients, from the little, old ladies who complained about chronic ailments to devastated small boys and everyone in between. These were not only our patients, they were our neighbors, and members of our community seeking our knowledge, guidance, and medical assistance to relieve them of horrific illnesses and injuries, and we did our best, with our era’s best knowledge, technological advancements and research, to help them in every single way we could. It’s not what you have today, so mock us all you want, but you cannot say we weren’t trying.”

Anytime I read such a compendium, one of the first things I think about is time machines. We all love the speculative concept of going back in time to talk to long-dead relatives, historical figures, and to experience our romanticized notion of living, if only for a moment, in a different time. The implicit warning books like The Mystery of The Exploding Teeth leave is, if some brilliant mind ever develops the technology to travel back in time, that pioneer taking one giant leap for mankind should check, recheck, and triple check to make sure they get one key component of their technology right before they leave: make sure you can get back. The authors of speculative fiction devote very little space to this need to get back to the present. It’s not very sexy, and no matter how much an author loves a character, they’re not concerned with the ramifications of their character getting stuck in another time period. They can play this short-term game with their characters, because their characters aren’t real. A real character who knows anything about the science influencing the medical community of the 19th Century should make getting back their primary concern, because while they will experience worldwide, historic fame for the technology of their contraption, if they’re not able to get back, they might not get to enjoy that fame.

a nice humbling read, great!

LikeLike