The Organic Sandwich

“I’m burping peanut butter,” she said.

“That’s funny, because I’m farting jelly. Now, if we could just get that guy over there in the corner, with a yellow-striped shirt on, to somehow make us some bread, we could have one hell of a sandwich.”

“That’s funny, because I’m farting jelly. Now, if we could just get that guy over there in the corner, with a yellow-striped shirt on, to somehow make us some bread, we could have one hell of a sandwich.”

“Who is he?” she asked.

“No idea, but look at him. If anyone can make bread, my bet is it’s someone who looks like him.”

You Should’ve Seen What I, More or Less, Saw

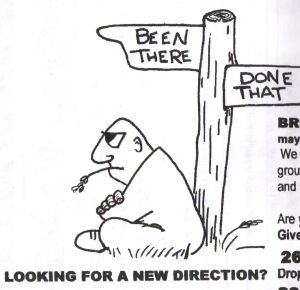

Arnold knew what life had to offer when I met him. He’d been-there-done-that. He knew there was nothing more to life while on the never-ending quest for something more. “This isn’t something more,” he said anytime we shared an experience. “This is something less than what I’ve experienced already. You schlubs, who think this is something more, just haven’t lived the life I have.”

Arnold lives his life pitying those who enjoy experiences. He’s already had them. A vacation is not as great as the one he had, a night out with a wild and crazy guy is not as fun as the one he had with a lunatic who knew how to have some fun. A weather anomaly is not as bad as the one he experienced in a different town, in a different year. “You think this is bad, you should’ve seen what I saw back when I was (whatever).” You Think This is Bad… will be the title of his biopic, if anyone has the excess cash necessary to fund such a project.

“Stick with the Beatles,” he says when we express adoration for some new musician who attempts to create music. It’s always interesting to me when music snobs (of which I am an avowed member) suggest that because group B is not as great as group A, we shouldn’t listen to B, or any of the other letters in the alphabet. “Are you saying they’re better than the Beatles? All right then.” Case closed. Nothing to see here. Matter resolved. Now enjoy your life of listening to nothing but the Beatles, you’ll thank me later. For some of us, music is life. A new release by some otherwise unknown artist fuels us in ways that are tough to explain to someone who has already heard the best. We have an appetite for something different, not better, not just as good, different. Arnold doesn’t have that gene. Music is background noise to him.

“Stick with the Beatles,” he says when we express adoration for some new musician who attempts to create music. It’s always interesting to me when music snobs (of which I am an avowed member) suggest that because group B is not as great as group A, we shouldn’t listen to B, or any of the other letters in the alphabet. “Are you saying they’re better than the Beatles? All right then.” Case closed. Nothing to see here. Matter resolved. Now enjoy your life of listening to nothing but the Beatles, you’ll thank me later. For some of us, music is life. A new release by some otherwise unknown artist fuels us in ways that are tough to explain to someone who has already heard the best. We have an appetite for something different, not better, not just as good, different. Arnold doesn’t have that gene. Music is background noise to him.

“It’s the Sun,” he says when we attempt to describe a Sunrise. “The Sun rises every day, and the average human being will see about 28,000 of them in their life on Earth.” All right, but how many do we look at, and how many do we see? “It’s the Sun.” For those who’ve experienced a Sunrise, appreciation suggests a level of cute and laughable naivete.

Arnold is not a crotchety, old man, but he will be one day, and I suspect he will refuse to appreciate anything on his death bed. He might even try to been-there-done-that death, “You think this is bad, you should’ve seen my life.” Death will mean nothing to him, because he will look forward to something more. “What if this is it?” we’ve asked him. Arnold won’t hear it. He’s locked in on the idea that nothing can top what he’s already done while being unimpressed with it in the moment and looking for something more. “What if there isn’t anything more?” We’re not attempting to open a can of worms. We’re not suggesting that there isn’t always something more. We’re suggesting that he might want to stop comparing life to what was, what could be, and maybe train a little more focus on what is, because we will all, eventually, find out if there is anything more soon enough.

I love to watch things on TV.

“Who do you think is going to win?” I asked Vito. Vito and I were watching two people get ready to play a game of pool from a neighboring table. We were so bored that I felt boring. We were absently watching a college football game between two boring teams. My question was so random that if Vito declared that he didn’t care who won at pool, and his ambivalence was convincing, I would’ve moved on without giving the matter a second thought. Vito didn’t do that, however, he tried to sidestep the question.

“I don’t know,” Vito said. “I really don’t. I haven’t watched them, and I cannot gauge their abilities.”

“I know you don’t know who’s going to win,” I said. “Either do I. That’s the fun of randomly picking a guy. We do that. Guys do that when we’re in a bar together. We randomly do things to have random fun. We could cheer these guys on in a way that makes them so uncomfortable that they ask us what’s going on. Then, we could tell them-”

“I’m not in the game of making predictions,” he said, interrupting me. Yet, he was into making predictions. He did it all the time, but he only picked overwhelming favorites, so he could be right. We all enjoy being right, and Vito was no different, except by the matter of degree he cared. He cared so much that when the two combatants were somewhat evenly matched, he refused to put his reputation on the line for what amounted to a guess. He dropped that “I’m not in the game of making predictions” into those occasions so often that I considered it his character-defining line. If someone with enough excess cash on them to make a biopic on his life approached me for ideas on a title, I thought this would be an excellent one.

“Let’s put a friendly wager on it?” I pressed. Vito squirmed. “Pick either one, and the loser buys the next pitcher.” Even though the pool balls were racked, these pool players took their time. They drank their beer slowly and chatted with another table near them. They stood astride their pool sticks, like warriors preparing for battle, while they chatted. I didn’t understand why these guys took their time. They paid by the hour for the table. Either they had too much money, or they liked being players more than they like playing.

When Vito said, ‘I haven’t gauged their abilities’ he meant it. He thought his abilities to gauge talent was his talent. If we bet on two girls playing hopscotch, Vito might take out a slide rule to measure the muscle mass in their thighs. He might want to talk to the players before making an assessment, and he might ask them to do a couple of run-throughs before reaching an assessment worthy of a Vito declaration. Even in a pool hall, on a boring and random Friday night, he hesitated, thinking I might bring my victorious bet back to the office and thereby ruin his reputation

“C’mon,” I said. “It’s one pitcher of beer.”

“I’m not a gambler,” Vito said.

“I’m not either,” I said, “but this might make this otherwise boring night a little fun.

“Sorry,” he said.

At this point in our article, the reader might think that the importance of Vito’s vaunted prediction record was all in his head. It wasn’t. To my dismay, I heard someone else say, “Vito predicted that” the morning after an overwhelming favorite demolished an underdog. “So, did I,” I said to interrupt the conversation this guy was having with a third party. “Everyone did. Everyone knew they would win,” I said to proverbially bite the head off the poor chap.

That was the only time anyone validated Vito’s prediction record, but it got under my skin when he would say, “Team A will beat team B, you heard it here first folks.” I couldn’t hide my disdain, and I always said something. I couldn’t abide by this violation of the bro code silently.

The primary driver of Vito’s need to establish a vaunted prediction record was that he wasn’t much of a sports fan. When he would predict a victory of the overwhelming favorite, I think he believed it gained him some entrée into our world.

“What does this do for you?” I asked him without offering my opinion. “What does this prediction game do for you?”

He said nothing.

“I have bad news for you. No one cares. Now, if you picked an overwhelming favorite and gave the underdog twenty points, or something, we might care, maybe, but you won’t do that, because you’re not a gambler. Have you ever predicted an upset?”

He said nothing. He just pulled his beer up to his mouth with a half-smile in a way that suggested he knew something I didn’t. That was it, I decided. That was his game, his mystique. His affectation in life was to suggest he knew something we didn’t.

“I’ll pick. The guy with yellow stripes,” I said. “Always bet on yellow stripes.”

“I’m not in the game of making predictions,” he said as if he never said it before.

“You watch too much TV,” we said. “Professional prognosticators, who use that line, get paid for analysis. They also get paid for being right and fired for being wrong. No one is going to pay you wooden nickel for your predictions, and no one is going to care if you’re wrong. You watch too much TV.”

For the record, yellow stripes won and Vito said, “I knew it,” after the match was over. I still don’t know if he meant it, or if he was being sarcastic, but that line has been a comedic mainstay in my repertoire ever since. I’ve used that line to sarcastically note that I made an impossible prediction after the fact. It’s also an ode to a scene in The Simpsons (S3, E21 The Frying Game) in which Carmen Electra dressed up as recently murdered Myrna Bellamy, and when Electra removed her costume to reveal it was Carmen Electra, Homer said, “I knew it.”

For the record, yellow stripes won and Vito said, “I knew it,” after the match was over. I still don’t know if he meant it, or if he was being sarcastic, but that line has been a comedic mainstay in my repertoire ever since. I’ve used that line to sarcastically note that I made an impossible prediction after the fact. It’s also an ode to a scene in The Simpsons (S3, E21 The Frying Game) in which Carmen Electra dressed up as recently murdered Myrna Bellamy, and when Electra removed her costume to reveal it was Carmen Electra, Homer said, “I knew it.”