“One day, everyone I knew had Billy Squier’s record Emotions in Motion, and the next day nobody mentioned his name.” It wasn’t that immediate, but it felt that way. Billy Squier had a long, relatively prosperous career, but there was a time, circa 1980-82, when the man had trajectory. Rock critics, corporate insiders, and his peers thought William Haislip Squier was the next big thing. At one point in his career, Billy Squier said, he was outselling Sinatra.

Emotions in Motion was one of the staple records of the era. Everyone I knew had Men at Work’s Business as Usual, Foreigner’s 4, Journey’s Escape, and Emotions in Motion. If someone didn’t have all of these albums, their collection just didn’t appear complete. All of these artists came out with other albums and had decent careers, but they would never achieve the peak of popularity they experienced during this 1981-1983 run. Our initial inclination is to feel sorry for these artists who experienced so much unimaginable success so early on in the careers when they were too young to appreciate it, but most artists never have such a run. The skilled, lucky, and timely ones do, and some have longer runs than others. Very, very few artists prove so popular that they can sustain a relatively high level of popularity throughout their career. Billy Squier’s run occurred early on in his career, but that run was so fruitful, with so many hit songs, that many predicted he would be one of the few to, at least, have a long, prosperous run. He was so huge that Andy Warhol agreed to design an album cover for him, and Jim Steinem agreed to produce one of his albums. Every run comes to an end, but the change in Billy Squier’s trajectory happened so quickly that many fans from the era still wonder what happened? “Of course I remember him,” many fans of 80’s music said, “Whatever happened to him?”

One look at his bio suggests a very simple answer, Billy Squier stopped writing chart-topping songs. He wrote chart-topping songs for the first few years of his career, and then he didn’t. No matter what happened in 1984, if Squier continued to write chart-topping singles, he would’ve overcome “the video”. Numerous others, including Billy Squier, say, “No, it was the video.” They say that his trajectory altered dramatically after “the video”. That just seems utterly impossible to those of us on the outside looking in. How could one video bring such a high-profile artist’s career down?

Well, “the video” was a bad. Even viewed in hindsight, alongside all of the horribly embarrassing videos made in artists’ names in the era, Billy Squier’s video for Rock me Tonite stands out as the worst videos made in the era, and according to the authors of the 2011 book I Want My MTV, it was the worst video ever made. “The authors of this book interviewed over 400 people, primarily artists, managers, filmmakers, record company executives and MTV employees. They said that none [of them] could agree on the best video, but all agreed that “Rock Me Tonite” was the worst.” The authors devoted an entire chapter to describe how and why this video was so bad, and how and why it diminished one of the biggest rock stars of the era.

Well, “the video” was a bad. Even viewed in hindsight, alongside all of the horribly embarrassing videos made in artists’ names in the era, Billy Squier’s video for Rock me Tonite stands out as the worst videos made in the era, and according to the authors of the 2011 book I Want My MTV, it was the worst video ever made. “The authors of this book interviewed over 400 people, primarily artists, managers, filmmakers, record company executives and MTV employees. They said that none [of them] could agree on the best video, but all agreed that “Rock Me Tonite” was the worst.” The authors devoted an entire chapter to describe how and why this video was so bad, and how and why it diminished one of the biggest rock stars of the era.

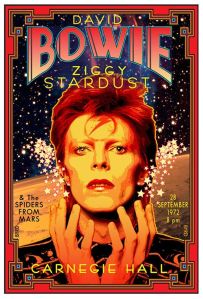

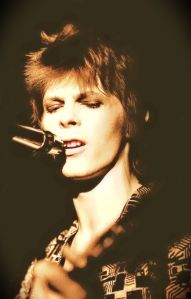

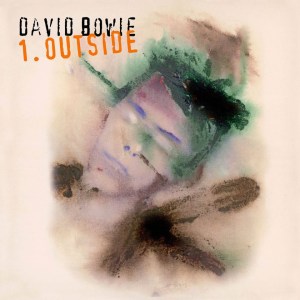

The counterpoint to the claim that a poorly conceived video can irreparably damage a recording artists career is Dancing in the Streets. Dancing in the Streets is arguably one of the top-five worst videos ever made with equally awkward dance moves and embarrassment for the artists involved. Yet, that equally bad, career-killing video that did little to tarnish the career and legacy of David Bowie and Mick Jagger. Those two artists, however, had stronger careers before their embarrassing video, and they created music after “their video” that they helped us forget their egregious misstep.

Rudolph Schenker of the Scorpions said, “I liked [Billy Squier] very much … then I saw him do the video in a very terrible way, and I couldn’t take his music seriously anymore.”

***

Right around the time of Billy Squier’s Emotions in Motion, I had my own money. I had a job, and I never had a job before. I also had disposable income that was not subject to my dad’s approval, and I wanted music. I didn’t know anything about who music magazines declared “who’s hot and who’s not”. I just knew that when I heard either Everybody Wants You and Emotions in Motion, I dropped on the floor and skated at my local Skateland, and every else I knew did too. I also saw Quiet Riot’s Metal Health cassette on the store shelves, and those two albums were the only ones I knew that catered to my need for hard charging guitars. My musical tastes were based on the influence of friends, what local, Top-40 radio Disc Jockeys decided to play, and what my neighborhood Skateland decided to play to try to get me on the floor. In these arenas, Billy Squier sat atop my Mount Rushmore, but so did Quiet Riot. I had the income, and I had the need. I purchased both.

I thought the Quiet Riot singles Come on Feel the Noise and Metal Health (Bang your Head) hit all the bullet points a young man and woman had, I was wrong. In one of the first lessons I learned about the difference between genders, the reaction to those songs was divided among the boys and girls circling the no-go zone in the middle of the skating room floor. The singles Everybody Wants You and Emotions in Motion, however, put everyone on the floor. The opening guitar riff from Everybody Wants You caused girls to shriek and guys to pump their fists as they rounded the floor. The speed skating and broad smiles that resulted were infectious. Bill Squier’s musical creations were so ubiquitous that everyone who was anyone wanted his songs in their home. So, what happened?

***

Some critics suggest that Billy Squier’s move away from guitar-based rock to keyboards and synthesized rhythms, on 1984’s Signs of Life, alienated many in his fan base. Others say that while that album had some guitars, they were mostly used as an afterthought to appease his fans. The Signs of Life album appeared to be Squier’s attempt to transition from heavy, hard-charging guitar-based music to keyboards and synthesized rhythms to stay up with the times, while trying to appease his guitar-driven fan base at the same time. He tried to appease all the people all of the time, in other words. The primary critiques I found of Billy Squier is that he tried so hard to keep it going after Emotions in Motion that he probably tried too hard, and he ended up becoming a parody of himself. (We should note that Signs of Life went platinum, which kind of surprised me when I read that, because Billy Squier was persona non grata in my social circles after Emotions in Motion.)

Some critics suggest that Billy Squier’s move away from guitar-based rock to keyboards and synthesized rhythms, on 1984’s Signs of Life, alienated many in his fan base. Others say that while that album had some guitars, they were mostly used as an afterthought to appease his fans. The Signs of Life album appeared to be Squier’s attempt to transition from heavy, hard-charging guitar-based music to keyboards and synthesized rhythms to stay up with the times, while trying to appease his guitar-driven fan base at the same time. He tried to appease all the people all of the time, in other words. The primary critiques I found of Billy Squier is that he tried so hard to keep it going after Emotions in Motion that he probably tried too hard, and he ended up becoming a parody of himself. (We should note that Signs of Life went platinum, which kind of surprised me when I read that, because Billy Squier was persona non grata in my social circles after Emotions in Motion.)

Anyone who studies any form of art knows that most artists are prone to become parodies of themselves at one point or another. Few artists in music, in particular, are able to reinvent themselves just about every time out, I cite David Bowie and Bob Dylan as two such exceptions to the rule. For the rest of the world, there is the Thelonius Monk quote, “A genius is the one most like himself.”

How does an artist stay true to themselves and their fans, while trying to reach out and broaden their fan base? Billy Squier had an idea. Rock historians and critics now call it “the video”. Prior to the short shelf life the video for Rock me Tonite experienced on MTV, the 1984 album Signs of Life was flying up the charts. It charted high on Billboard’s top selling charts, but it stalled and eventually fell after the video for the song Rock me Tonite premiered on MTV. Some, including Billy Squier, say the video ruined his career.

Why was it so bad? Watch it. There’s nothing anyone can say to describe how bad something is than to say, ‘just watch it for yourself.’ Wikipedia provides the most succinct description of the video, “It shows Squier waking up in a bed with satiny, pastel-colored sheets, then prancing around the bed as he gets dressed, ultimately putting on a pink tank top over a white shirt. At the conclusion he leaves the room with a pink guitar to join his band in performing the song.” The song also shows Squier putting on a shirt, then ripping it off in an apparent display of lust that just happens to reveal his “good-looking sexy chest.” There’s also the requisite sprawl on the ground in which the sexy beast pulls themselves forward on the ground to evocatively display the character’s primal lust. I don’t know which video director displayed this first, but it became a staple in 80’s videos.

There is some debate regarding why the video was so bad. Some, including Squier, suggest he appeared too feminine in the video, but we could say that that characteristic didn’t alter David Bowie’s trajectory, Marc Bolan’s, Twisted Sister’s, or even to a lesser degree Alice Cooper’s (Cooper was more about shock value and makeup than he was femininity). Others say it was more about Billy Squier’s ill-conceived dance moves. Were the dance moves feminine? Yes, but anyone who watches “the video” knows that its problems do not begin and end with “being too feminine”. The video is just awkward, and so weird, and so out of the artist’s personae. Even those of us who didn’t know the persona he had before the video can watch it and know he probably shouldn’t be doing that in public. “But,” the defenders of Squier said, “These were the same dance moves he did in concert every night on tour.” We’ve all been to those concerts, and we’ve all cheered any dance moves the lead singer engages in. It’s almost as if we’re starved for entertainment, and a dance move here and there, regardless the quality of the moves, is met with ecstatic approval as it adds to the collective energy we can feel from the speakers. Even ill-considered, poorly choreographed dance moves seem more in context, in an auditorium, than they do from the perspective of watching them on TV. If Saturday Night Live tried to do a spoof on all of the awkward staples of 80’s videos, they couldn’t have done much better than Billy Squier did in this video. The video reminds us of the conversations the fellas had at the high school dance, seeing all the beautiful girls on the other side of the floor, wishing we could dance. “I can dance,” one of our friends said, and he showed us something he probably practiced a million times in the mirror with no objective criticism to inform him how hilariously bad his moves are. We can only imagine that Squier watched all of the hot, risqué videos of the era, from Madonna and Prince, and thought, “Hell, I can do that.”

As Squier said, “I was a good-looking sexy guy.” The video appears to be Squier’s attempt to show the world how good-looking and sexy he could be, to use his natural assets to make it to the next-level. Perhaps, he thought this video would help him make the leap from rock icon to sex symbol. We can only guess that Squier designed Rock me Tonite to elicit comments like “steamy” and “too-hot-for-TV” comments to attract the prized female demographic. The use of pink, as the predominant color in the video, reinforces that guess.

As Squier said, “I was a good-looking sexy guy.” The video appears to be Squier’s attempt to show the world how good-looking and sexy he could be, to use his natural assets to make it to the next-level. Perhaps, he thought this video would help him make the leap from rock icon to sex symbol. We can only guess that Squier designed Rock me Tonite to elicit comments like “steamy” and “too-hot-for-TV” comments to attract the prized female demographic. The use of pink, as the predominant color in the video, reinforces that guess.

After the fantastic success of Emotions in Motion, we can only imagine that record company executives sat Billy Squier down in a boardroom to discuss his future. In this boardroom, Public Relations advisors entered with charts and graphs detailing Billy Squier’s popularity from 1980 to 1982, with comparative lines listing his male-centric base against a projective arrow of what his numbers could be with some kind of paean to the female demo. Whether Squier saw the trends and tried to up his game, or he received some bad advice, his gambit failed miserably.

The fallout from the video was so immediate that Squier claims he went from packed stadiums before the video to half-filled auditoriums almost overnight. He fired both of his managers within a month of the video’s airing, and he tried to put all the blame the video on director Kenny Ortega.

“If anything, I tried to toughen the image he was projecting,” [Kenny Ortega] told the author of a 1986 book about the record industry. He claims he and the video’s editor had their names taken out of the credits when they got frustrated over their lack of creative input. “Let there be no doubt, ‘Rock Me Tonite’ was a Billy Squier video in every sense. If it has damaged his career, he has no one to blame but himself.”

Research shows that the video for Rock Me Tonite didn’t kill Billy Squier’s career, as the album Signs of Life went platinum, and the next two albums both sold 300,000 a piece. How many artists would kill to sell 300,000 albums? The video did appear to alter the trajectory of his career that peaked with the multi-platnium album Emotions in Motion, but it’s entirely possible that his run just ended, as most runs do. The most imperfect way to solve the dilemma that appeared to haunt Billy Squire to his dying day is what would’ve happened to Billy Squire’s career if he never made “the video”. While I understand that rappers use his samples in their songs, his legacy and overall influence just isn’t as strong as a Marc Bolan’s is. Both artists experienced massive success early in their careers, roughly ten years apart, and their sales numbers leveled off after a couple albums. Comparatively speaking, they both experienced decent runs and comparatively long careers in an otherwise unforgiving industry. Neither of them were one-hit wonders, in other words, as they both ended up having about ten chart-topping singles. At some point in their careers, they both got lost in the shuffle, and their runs somehow ended. When we write somehow, Billy Squier might correct us, if he were alive today, saying it was “the video”. Yet, if he came out with another chart-topping song or album, he could’ve put the ill-advised, poorly timed, and utterly embarrassing video behind him, but he never did.