They were hairy and kooky, obnoxious and a little spooky, the metal bands of the 80s. As fashionable as it was to love these (mostly) L.A.-based heavy metal in the 80s, it became just as fashionable to openly despise them in the 90s.

I loathed them too, until a young co-worker, who was discovering them for the first time, said, “Hey, they’re not [Bob] Dylan, or [John] Lennon, I get that, but c’mon, they’re fun.” I immediately dismissed that line, because the guy was a doofus. His musical tastes did not define his doofosity, but it was everything else that led me to dismiss just about everything that came out of his mouth. Yet, to my amazement this simple line, from such a simpleton, fundamentally changed the way I listen to music today. I went through a they’re-not-this-that-or-the-other-thing phase, until I eventually turned into a “C’mon, they’re fun” guy too.

I’d love to write, right here, that the self-indulgent critics’ call for important, meaningful music, never got to me, but the pressure to denounce hairy metal from the 80s came from every “cool kid” corner of my life. Prior to loathing them, I went through a long and expensive heavy metal phase when I was a teen. I spent almost all of my minimum wage paychecks on cassette tapes of every major, and many minor Los Angeles-based, hair, glam metal band out there.

I’d love to write, right here, that the self-indulgent critics’ call for important, meaningful music, never got to me, but the pressure to denounce hairy metal from the 80s came from every “cool kid” corner of my life. Prior to loathing them, I went through a long and expensive heavy metal phase when I was a teen. I spent almost all of my minimum wage paychecks on cassette tapes of every major, and many minor Los Angeles-based, hair, glam metal band out there.

When I aged out of it, I sought serious, brilliantly complex music, but when doofus said what he said, I realized that I was trying to make myself into a serious adult, because I wanted adults else to take me seriously. Doofus reminded me that we can all seek complex arrangements in our music from artistic musicians, but let’s not forget to keep it fun.

With his succinct condemnation of my self-importance and self-indulgence, doofus reminded me of the simplistic brilliance of all those years ago. The book Nothin’ but a Good Time also reminded me, more recently, that the hairy, glam metal music of the 1980s never claimed to be anything more than what it was. Say what you want about the bands of this era, and the music they wrote, but they never tried to be vital or important. They never wrote a seven minute opus on the Fall of the Roman Empire and how it might correlate with the modern rise of technology. The music of the Los Angeles-based hair bands were all about having a party, abusing their body with whatever substances they could find, having random and consensual, conjugal visitations, and any other forms of excess they could find to have a good time. The book also pointed out that they didn’t mind practicing what they preached.

Shortly after I grew out of my love of hairy metal, I sought clever and complex music, but I’ve never enjoyed deep songs with meaningful lyrics. This might be a result of listening to so many thousands of hours of metal music in my teens, but I have always considered deep, meaningful songs so silly. They do nothing for me. Most of the time, when I hear a lyricist attempt to write deep, profound lyrics, I think of Fredo from The Godfather, “I’m smart! Not like everybody says… like dumb… I’m smart and I want respect!”

Shortly after I grew out of my love of hairy metal, I sought clever and complex music, but I’ve never enjoyed deep songs with meaningful lyrics. This might be a result of listening to so many thousands of hours of metal music in my teens, but I have always considered deep, meaningful songs so silly. They do nothing for me. Most of the time, when I hear a lyricist attempt to write deep, profound lyrics, I think of Fredo from The Godfather, “I’m smart! Not like everybody says… like dumb… I’m smart and I want respect!”

We’ve all read critics pour through lyrics for the deep meaning the author intended, but most of them either have something to do with something political or social, or they contain some oblique, or over the top, reference to drug use. I listen to that music, and I repeat it numerous times, but the lyrics don’t affect me in anyway. Vocals, and vocal inflections, should be used as another instrument in a song. If they do it well, I’ll listen, but I don’t understand why we should care what Thom Yorke of Radiohead has to say about his view of the world any more than we do Bret Michaels of Poison. In this vein, Michaels’ lyrics might be more respectable, because he doesn’t engage in any of the “look at me, ain’t I smart?” type of the self-indulgent lyrics we find in Yorke’s work.

Most of the “vital and important” music critics of the era loathed heavy metal, but we didn’t really care. We didn’t need Nothin’ But a Good Time, and that served to undermine the power of the music critics. The critics knew that most of the hairy metal bands didn’t know how to play their own instruments, and they panned them for not only ignoring socially significant issues but damaging some. They loathed these bands for thumbing their nose at consequential issues, and they deemed them inconsequential. No one I knew cared. We wanted to play heavy metal music at our parties, and we wanted to play that same music in our cars on the ride home from work to remember those parties. The book Nothin’ But a Good Time reminded those of us who loved it that there was a time when we didn’t take ourselves so seriously, and we knew we weren’t vital and important. We were silly and stupid, because we were kids, and we wanted our music to be silly and stupid too. We didn’t want to hear what critics said we should be.

How bad were the hairy metal bands of the 80s? How good were they? It depends on who you ask and when you asked them. As the book points out, the era was all about timing. Those who were in a Los Angeles-based heavy metal band between 1984 and 1988 learned how the other half lives for a while, and they indulged in every excess they could think up. If a heavy metal, glam band had all of the above and they released an album as late as 1989 to 1990, a major record label probably signed them, but every album they made went straight to the $.99 bin. The idea that sales are all about timing is not a novel concept of course, but was any rise-and-fall of a musical genre as stark as what happened to heavy metal in the 80s? Disco? maybe.

Were Motley Crue (‘83), Ratt (’84), Poison (‘85) that much better than Bang Tango (’89), Junkyard (’89), or Dangerous Toys (’89)? When we listen to classic rock radio today, which bands do we hear? How many of us even know the latter three? One would think that if the latter bands had music that was just as good that they would eventually rise to some levels of prominence. They didn’t, in part, because the more prominent bands of the era tapped into a time and place of the zeitgeist that will presumably never die in some quarters.

Were Motley Crue (‘83), Ratt (’84), Poison (‘85) that much better than Bang Tango (’89), Junkyard (’89), or Dangerous Toys (’89)? When we listen to classic rock radio today, which bands do we hear? How many of us even know the latter three? One would think that if the latter bands had music that was just as good that they would eventually rise to some levels of prominence. They didn’t, in part, because the more prominent bands of the era tapped into a time and place of the zeitgeist that will presumably never die in some quarters.

What happened in the intervening years, some of those band members interviewed in Nothin’ but a Good Time say the dynamic in the industry experienced a subtle shift when Guns N’ Roses changed it a little in 1987. Others not in the book, say the industry tilted further away from the “Rock and Roll all nite and party every day” rock theme when the funk-rap hybrid bands Faith No More (’89) and Red Hot Chili Peppers (first noteworthy album ’89) arrived on the scene, but most acknowledge that the Seattle, grunge movement led by Nirvana’s Nevermind in 1991 sounded the death knell of the hairy metal of the 80s.

To read about 98% of most modern critics, the modern reader might believe that Kurt Cobain single-handedly killed ‘80’s hairy metal. The critics write this, I think, because they loved everything about Cobain, Nirvana, and the single Smells like Teen Spirit. They love the narrative that ten minutes after Smells like Teen Spirit aired on Mtv, everyone knew the heavy metal movement was over. Some of the artists interviewed in this book, however, suggest that Slash might’ve done more to end the mid-80s version of hair metal than Cobain. I consider that an intriguing notion, considering that most put the heart of heavy metal’s reign over the music industry between ’84 and ’89, and that it began to wane two years before Nevermind was released. As factual as that statement appears to be, according to record sales and Mtv plays, it’s not as compelling as the narrative that suggests one band, one man, and one song ended it all. Others claim that other Seattle artists Mother Love Bone, Alice in Chains and Soundgarden did something so different in the years preceding Nevermind that they laid the times-they–are-a-changing groundwork to pave the way for Nevermind. Some musicians claim that the King’s X 1989 album Gretchen Goes to Nebraska laid the groundwork for what some call the Seattle sound, and others call grunge. Regardless the who, what, and whens of the argument, most agree that Nevermind did put the final stake in the heart of the dying carcass that was the hairy metal of the 1980s.

***

As compelling as the argument of the death of heavy metal is, the tale of the birth of heavy metal might be as interesting. Almost every artist of the era lists Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin as the forefathers of their sound, and others state that the first Black Sabbath album, AC/DC’s Back in Black, and Quiet Riot’s Metal Health, and Twisted Sister’s Stay Hungry all played a role. The over-the-top looks, the stage theatrics, and the simple, arena, sing-a-long rock songs intended for nothing but fun, however, belong to KISS. Put simply, if KISS didn’t rule the airwaves of the 70s, the early hair metal movement of the 80s probably doesn’t happen.

As compelling as the argument of the death of heavy metal is, the tale of the birth of heavy metal might be as interesting. Almost every artist of the era lists Aerosmith and Led Zeppelin as the forefathers of their sound, and others state that the first Black Sabbath album, AC/DC’s Back in Black, and Quiet Riot’s Metal Health, and Twisted Sister’s Stay Hungry all played a role. The over-the-top looks, the stage theatrics, and the simple, arena, sing-a-long rock songs intended for nothing but fun, however, belong to KISS. Put simply, if KISS didn’t rule the airwaves of the 70s, the early hair metal movement of the 80s probably doesn’t happen.

Nothin’ But a Good Time mentions KISS a couple of times, but for the most part this book strives to cover the scene in this era, and it provides little backdrop for who (other than Quiet Riot and Twisted Sister) might have inspired it. Yet, if KISS inspired the early years of the movement, it would be a stretch to say they were the catalyst for the entire era. KISS came out in ’73, and they hit their peak commercial value between ’75 and ’77. Why did it take seven years for bands like Poison and Motley Crue to take their influence to platinum success?

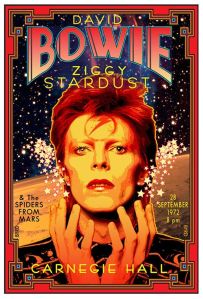

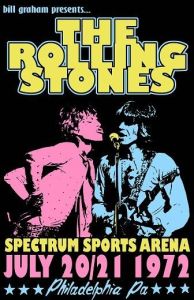

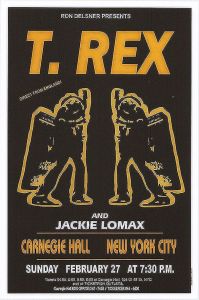

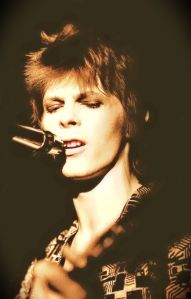

The missing link, in my humble opinion, arose from a subtle shift the British band Def Leppard made away from their more traditional heavy metal sound from the KISS, AC/DC sound to the more polished, David Bowie, T. Rex catchy pop-metal sound that proved more radio friendly when they made the relatively successful High N’ Dry in ’81. In ’83, Def Leppard took that concept up a notch with the release of Pyromania. That album’s success did not happen overnight, but in my world, no one I knew had ever heard of a group called Def Leppard on Thursday, but by Monday, everyone I knew was wearing the Def Leppard Union Jack sleeveless T-shirt. The groundswell was almost that immediate.

The primary difference between Def Leppard and KISS, in my world, was defined by every teenaged girl I knew. I knew teenage girls who liked KISS, especially the song Beth, but when Def Leppard put Pyromania on the shelves, every girl I knew suddenly loved a rock band. When the songs from Pyromania hit the radio, it was the closest thing to Beatlemania that I’ve ever experienced. Every teenage girl I knew listened to Pyromania and when teenage girls love something that much, teenage boys pay attention, and they eventually learn to love it.

The success of Def Leppard’s Pyromania (’83) led to Poison’s success (in ’85), and Motley Crue’s shift from their KISS-inspired (’83) album Shout at the Devil to the more female friendly Theater of Pain (in ’85). The formula Def Leppard set (by selling 6 million albums at the time) was to release a hard rock single followed by a more radio friendly ballad led every 80s heavy metal act who followed, to include a more female friendly ballad. (This formula started before Def Leppard, but they appeared to reignite it.)

The book Nothin’ But a Good Time begins right about here. The book doesn’t mention the integral role that I think Def Leppard played, but after the success of Pyromania, every major label tried to sign their own version of Def Leppard/KISS between 1984 and 1988. Most metal bands signed during this era went gold (selling 500,000 units sold), and some went platinum (1,000,000 units sold) to multi-platinum. As evidence of how crazy this signing spree became, a member of a band called Bang Tango said, “We weren’t even a real band when we were signed, and we had to learn quickly.”

Were most of the 80s hair metal bands ridiculously excessive? Were they politically incorrect? Did they have the lyric “baby” in every song, at least once? Were they everything critics loathe? The answer is D, all of the above. No one cared. When I write that we didn’t care about the critics, that shouldn’t be limited to the “who cares what the critics think?” trope that bands drop about critics. I’m talking about genuine, almost total obliviousness. We may have dropped a “You know the critics hate these guys right?” To which, the other guy would say, “Really? No, I didn’t know that.” And that was the end of the discussion in the non-cerebral and non-political party we teenagers were all having for a majority of the mid-80s.

At some point, the party we were all having with the L.A.-based, hair metal, glam bands had to end. The definitions of when and how this happened differ, but it did end. Some bands were still being signed to major record companies, and in this book those bands said that they paid their dues, and they felt like they wrote a decent album, but the record company didn’t promote them the way they might have just two years prior. They claimed that they were just as talented, or more so, than other bands who made millions two years prior. They missed the signing spree, and the multi-platinum awards for any band who could string together a halfway decent heavy metal ballad. They missed the crucial money making part of the era by about two years.

For those of us who were young and easily-influenced teenagers during this era, the polished pop metal to heavy metal music they produced will always be “ours”. It seduced us into believing life could be fun, and that it could be one big party that doesn’t have to end. Logic dictates that everything must end, however, and there came a point when glam metal needed to die. An era defined by excess eventually became so excessive that it became a parody of itself, and those of us who once loved it developed a love/hate relationship that eventually came to an end when young, rock enthusiasts reminded us how fun the music from the era used to be. Even with that, however, some of the artists interviewed in the book Nothin’ But a Good Time now admit that it became obnoxiously excessive, and it had to die under its own weight. Someone had to come along and burn the field to prepare for the harvest of something different and new. These facts about life and art can be as hard to accept as they are to deny, but as the book states a number of the top-tier bands of that era have experienced a certain rebirth from younger crowds who missed it the first time around and older crowds who seek the nostalgia of the acts.

“Write jokes, get paid,” was the philosophy Jay Leno followed throughout his career in comedy. He also preached this to his fellow comedians who thought they could and should use comedy to change the world. “That’s all such nonsense.” Leno reportedly replied. “It’s all about write jokes, get paid.” The glam metal of the ’80s followed this philosophy. They wrote fun, little meaningless songs that they hoped young people would enjoy so much that they might run to their local record store and buy, and we did, by the millions. The music was not important, vital, or consequential, but those of us who lived through the era thought it as a lot of fun. When we comb through music timelines, with critics who write such things, we’ll never see them list our favorite artists on the “most influential artists of the eras” lists they write. Those of us who lived through the era know what a ridiculous time it was in music, in terms defined by music critics, but if we were to write a eulogy on the time period, we might say something like, “Was it a meaningless era that focused on a lot of dumb, superficial stuff? It was, but that was the kind of party we were having back then. Sorry, you missed it.”

There are no reported connections between the band members choosing the name, KISS, and the acronym, the latter of which many state stands for Keep It Simple, Stupid, but has any rock band ever embodied that acronym better than KISS?

There are no reported connections between the band members choosing the name, KISS, and the acronym, the latter of which many state stands for Keep It Simple, Stupid, but has any rock band ever embodied that acronym better than KISS?  My neighborhood friends and I used to pretend that we were KISS-in-concert. I was The Spaceman, my best friend was The Demon, and his little brother was Catman. (Nobody wanted to be Starchild.) We would play air guitar and air drums in an area they called the basement. I would arch back like Ace did when he played his solos, because I thought that was one of the coolest things ever, and my friend waggled his tongue, spat blood, and pretended to blow fire with Gene. So, while the rest of you were listening to the important and vital music, we were having fun.

My neighborhood friends and I used to pretend that we were KISS-in-concert. I was The Spaceman, my best friend was The Demon, and his little brother was Catman. (Nobody wanted to be Starchild.) We would play air guitar and air drums in an area they called the basement. I would arch back like Ace did when he played his solos, because I thought that was one of the coolest things ever, and my friend waggled his tongue, spat blood, and pretended to blow fire with Gene. So, while the rest of you were listening to the important and vital music, we were having fun.  KISS albums were chock full of silly, simple songs that won’t move you spiritually or cause anyone to think of the philosophy of Epicurus, but as the aphorism that some attribute to Leonardo da Vinci says, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” If you consider it a stretch to attach anything KISS did to the term sophistication, I feel you, but how much effort goes into achieving complex sophistication, and how much restraint does it require to keep it as simple as possible?

KISS albums were chock full of silly, simple songs that won’t move you spiritually or cause anyone to think of the philosophy of Epicurus, but as the aphorism that some attribute to Leonardo da Vinci says, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” If you consider it a stretch to attach anything KISS did to the term sophistication, I feel you, but how much effort goes into achieving complex sophistication, and how much restraint does it require to keep it as simple as possible?  I used to denigrate people who listened to Whitney Houston and Celine Dion, in the manner people now denigrate the average KISS fan, but I realized the market is wide enough and divergent enough to welcome all. You can be a KISS fan, a Radiohead fan, or a Mariah Carey fan and know that no one is superior or inferior. They just enjoy listening to different types of music, and why do you care so much that they do? I choose Radiohead as an example of the complete opposite of KISS, on the musical spectrum, among mainstream acts. Radiohead writes complicated structures, with deep, provocative lyrics, and I am a huge fan. The question is do they write sophisticated material for the purpose of being sophisticated, so all their fans can prove their sophistication by saying that they enjoy listening to more sophisticated music? They get it, you don’t, because you’re a KISS fan, and they’ll spit the latter in the most condescending tone possible. KISS wrote simple, party music. Everyone knows who they are. Everyone knows they were a toe-tapping, foot stomping band who rarely tried to be something they weren’t (The Elder and Carnival of Souls excepted).

I used to denigrate people who listened to Whitney Houston and Celine Dion, in the manner people now denigrate the average KISS fan, but I realized the market is wide enough and divergent enough to welcome all. You can be a KISS fan, a Radiohead fan, or a Mariah Carey fan and know that no one is superior or inferior. They just enjoy listening to different types of music, and why do you care so much that they do? I choose Radiohead as an example of the complete opposite of KISS, on the musical spectrum, among mainstream acts. Radiohead writes complicated structures, with deep, provocative lyrics, and I am a huge fan. The question is do they write sophisticated material for the purpose of being sophisticated, so all their fans can prove their sophistication by saying that they enjoy listening to more sophisticated music? They get it, you don’t, because you’re a KISS fan, and they’ll spit the latter in the most condescending tone possible. KISS wrote simple, party music. Everyone knows who they are. Everyone knows they were a toe-tapping, foot stomping band who rarely tried to be something they weren’t (The Elder and Carnival of Souls excepted).