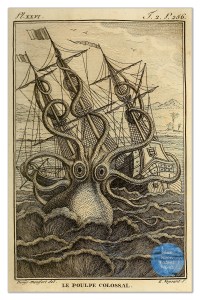

“Beware the Kraken!”

The Vikings of Nordic lore cried after encounters with the primal, savage beast we call the octopus, and to the uncharted waters in which they feared encountering larger and more primal, savage beasts, the Vikings added: “here, there be monsters”. They knew the extent of their travels and the beasts they encountered there, and anything beyond that excited their imagination in the most horrific ways. We can laugh at such assumptions now, as we know more about those uncharted waters, the octopus, the squid, and the various cephalopods that roam our seas, but we still have the propensity to fill in the gaps of our knowledge by designating anything we don’t understand as monstrous. The subjects of our fear might vary, but the animal instinct provokes us to fear that which we don’t understand.

When the Vikings witnessed these boneless sacs of flesh display high levels of intelligence and emotion, the cephalopods they encountered probably freaked them out so much that they assigned evil characteristics to it. When they didn’t understand it, they assigned a “here, there be monsters” moniker to their unimaginable extent of their intelligence. We know enough about the psyche of the octopus now that we’ve removed that moniker, but we’re still fascinated by the capacity for their levels of intelligence, emotion, and even friendliness.

The problem for those of us with more modern knowledge and understanding is that when we witness the characteristics that freaked the Vikings out, we tend to exaggerate our findings in the opposite direction, in our attempts to right the wrongs of the bygone era. “They’re not beasts or monsters. They are emotionally complex, very intelligent creatures,” observers of the octopus now report. “They’re sophisticated beyond our comprehension, and we just don’t know what we don’t know yet, but I can tell you what I know and what I saw.” Our propensity to exaggerate what we don’t understand can be equal to the Vikings’, in the opposite direction. The Vikings assigned primal, beastly, and supernatural characteristics to that which they didn’t understand, and we assign anthropomorphic, spiritual, and ‘beyond our current comprehension’ qualities to fill in the blanks of what we don’t understand. As with the Vikings, we see what we want to see, and we deduce what we want to deduce from our observances, and the truth probably lies somewhere in the middle.

“Octopuses may have originated from another planet!”

If you’re anything like me, you’ll click on any article that lists the octopus in its title. I don’t know if the popularity of such stories speaks to the popularity of the octopus, aliens from another planet, or our love of scary stories that play on our fear, but this story was everywhere in my newsfeeds.

Before reading these article, I realized that the whole octopuses-are-aliens creates a very natural gravitational pull that links them together in our psyche. Researchers suggest that the octopus might have a level of intelligence beyond our comprehension and alien enthusiasts always say that if we ever meet an alien, we’ll discover a level of intelligence “beyond our comprehension.” The latter is speculative, the former might be so exaggerated as to be speculative. I know, we don’t know what we don’t know, but that’s pretty much what speculative means when it comes to conjecture of this sort. If we can take a step back and view these two separately, it makes sense that we link them together.

The other thing these stories did for me was reignite my fascination with the octopus, and in my research I found a scientifically-backed theory that might blow your mind. I’m not going suggest that the reader take a seat, as I am almost biologically predisposed to avoiding clichés like, “You might want to sit down for this,” but if anything happens to anyone while reading the final third of this piece, I hereby absolve myself of any responsibility for injuries that occur if you’re not making sure you’re seated by the time you reach this info. Readers might also want to consider the pelvic strap and waist restraints the medical supplier Pinel provides before continuing.

Those of us who love stories about the surprisingly complex brain of the octopus have heard a myriad of stories regarding the ability the octopuses have to figure out puzzles and mazes. We’ve also heard tales of how they can escape the best, most secure aquariums, and we’ve heard about how a couple of SCUBA divers played hide and seek with an octopus, but have you ever heard that scientists now suggest that octopuses might be able to manipulate their molecular structure? Woh! What? I know, hold on, we’ll get to that.

A writer for Wired, Katherine Harmon Courage, has presumably heard all of the stories, and she has an interesting, provocative idea for why we should continue to explore the octopus for more stories though research, as they might prove instrumental in developing a greater understanding of the human mind.

“If we can figure out how the octopus manages its complex feats of cognition, we might be closer to discovering some of the fundamental elements of thought –and to developing new ideas about how mental capacity evolved.”

Arms Have Rights Too!

As stated in the previous installment of this series Octopus Nuggets I, the octopus has more neurons in its arms than it does in its brain, and we all assume the arms and brain work in unison to achieve a prime directive, but what if one of the arms disagree? As Scientific American states, “Like a starfish, an octopus can regrow lost arms. Unlike a starfish, a severed octopus arm cannot regrow another octopus.” So, if the octopuses central brain directs one of the arms to perform a particularly dangerous task, do the arms have the cognitive capacity to rebel against the central brain? Do the arms ever exhibit self-preservation qualities? Does an arm ever say something equivalent to, “I saw what you did to arm four last week, and I witnessed you grow another arm, good as new, in such a short time. I do not consider myself as expendable as arm four was. As you’ve witnessed over the last couple years, I am a quality arm who has served you well,” the sixth arm says to brain. “Why don’t you ask arm number seven to perform what I consider an unnecessarily dangerous task? We all know that he has been less productive year over year.” I am sure that no arm has an independent consciousness of its own existence in this sense, and that they largely function to serve the greater need, but how much autonomy do these arms have?

Blue Bloods

How many of us believed the tales our grade school friends passed around that human blood is actually blue, and that it only turns red when introduced to oxygen? I believed it in grade school, because why wouldn’t I? I could see my veins, and they were blue. One plus one equals two. The fella who dropped that fascinating nugget on me was far more intelligent than I was, and he was far more sciencey. Laurie L. Dove writes in How Stuff Works that the octopus actually does have blue blood, and it’s crucial to their survival.

“The same pigment that gives the octopus blood its blue color, hemocyanin, is responsible for keeping the species alive at extreme temperatures. Hemocyanin is a blood-borne protein containing copper atoms that bind to an equal number of oxygen atoms. It’s part of the blood plasma in invertebrates.” She also cites a National Geographic piece by Stephan Sirucek when she writes, “[Blue blood] also ensures that they survive in temperatures that would be deadly for many creatures, ranging from temperatures as low as 28 degrees Fahrenheit (negative 1.8 degrees Celsius) to superheated temperatures near the ocean’s thermal vents.”

Freakishly Finicky

A Wired piece reports, “If you asked Jean Boal, a behavioral researcher at Millersville University about the inner life of octopuses, she might tell you that they are cognitive, communicative creatures. Boal attempted to feed stale squid to a row octopuses in her lab and one cephalopod, the first in line, sent her a clear message: It made eye contact when she returned to it after feeding all the others, and it used one of its arms to shove the stale squid down a nearby drain, effectively telling Jean Boal that the stale food would be discarded rather than being eaten.”

Most animals are not finicky. Animals who fend for themselves in the wild, in particular, will eat just about anything they can find to sustain life, but depending on what they eat, it could cause disease and death. They don’t know any better, of course. The idea that a more domesticated animal, might display more preferences is not the fascinating element of this story, as for most of them food is not as scarce.

The freaky almost unnerving elements of this story, for me, lay in the details of the Jean Boal’s story. The idea that an animal might exhibit a food preference relays a higher level of intelligence, but I’m not sure if that level of intelligence surpasses that of the dog or the cat. The eerie part occurred in contemplating how the octopus relayed its message to Boal. Boal suggested that she fed the stale squid to a number of her octopus subjects, in their respective tanks, but after she finished feeding all of the octopuses, she returned to the first octopus she fed, and in her characterization of the episode, she declared that it waited for her to return. It looked her in the eye when she returned, and it established eye contact with her. Once it felt it established that it had her attention, the octopus shoved the stale squid down the drain, maintaining eye contact with her throughout the act. We weren’t there, of course, so we can only speculate how this happened, but Boal makes it sound like the octopus made a pointed effort to suggest that not only was it not going to eat stale squid, but it was insulted by her effort to pass it off as quality food, and it wanted to correct her of such foolish notions in the future.

We all anthropomorphize animals. Even if it operates from a flawed premise, it’s entertaining. It helps us connect with some animals from our perspective on the world. Dogs and cats might display dietary preferences, for example, but how many of them wait for a human to return, so they can be assured that the message will be received that they don’t care for the food, and how many will look the humans in the eye before discarding the food in such an exclamatory manner? I don’t know if you’re like me, but the thought that creeps me out is I thought I had a relatively decent frame for how intelligent these beings were, and that frame was a generous one. Boal may have been more generous in her characterization of this moment, but it remains fascinating to think the octopus might have these capabilities.

Rewriting the RNA

The following section contains elements I warned you about in the disclaimer. If you’re anything like me, you’ve found the details of the research on the octopus as fascinating, illuminating, and a little unsettling. I write unsettling, because we find comfort in the idea that humans are so much more intelligent than than every other species. In many cases, our superior intellect is the reason we’ve been able to survive so many scrapes with other animals, and it’s the primary reason we’ve survived so long. It’s for this reason, and others, that I consider this next part so mind-blowing that I feel the need to reiterate the need for the reader to set up some reinforcements behind you if you insist on remaining upright while reading.

The following section contains elements I warned you about in the disclaimer. If you’re anything like me, you’ve found the details of the research on the octopus as fascinating, illuminating, and a little unsettling. I write unsettling, because we find comfort in the idea that humans are so much more intelligent than than every other species. In many cases, our superior intellect is the reason we’ve been able to survive so many scrapes with other animals, and it’s the primary reason we’ve survived so long. It’s for this reason, and others, that I consider this next part so mind-blowing that I feel the need to reiterate the need for the reader to set up some reinforcements behind you if you insist on remaining upright while reading.

Recent scientific discoveries suggest that the octopus can edit their own ribonucleic acid (RNA). Boom! How are you doing? Did you forget to remove all sharp objects behind you? If the only thing keeping you upright is the idea that you kind of, sort of, don’t know what RNA is? Don’t worry, I had to look it up too. The Google dictionary defines RNA as an enzyme that works with deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in that it “carries instructions from DNA for controlling the synthesis of proteins, although in some viruses RNA rather than DNA carries the genetic information.”

For those who don’t consider the octopuses ability to edit its RNA a “Holy stuff!” fact, think about this. The next time you’re in your man cave engaged in a spider solitaire marathon, some octopus somewhere is in their cave re-configuring their molecular structure to redefine their characteristics in a manner that they hope will help them survive their next shark attack. An example of this might be the defense tactic we talked about in Octopus Nuggets I: the pseudomorph. To illustrate this, let’s anthropomorphize an octopus, for your reading pleasure, and call our octopus Ralph.

Ralph narrowly escaped a harrowing shark attack unharmed. It scared him of course, and as he cooled down in his den, allowing his heart rate to slow, he realized that that shark was nowhere near as confused by his ink cloud as shark’s had been his whole life. Was that shark an aberration, Ralph wondered, or do I now have to adapt to the shark’s adaptation? Ralph didn’t know if what he just survived was a freak occurrence, in that one shark had such experience with ink clouds that it knew better, or if all sharks had adapted, but he knew he could no longer rely on a simple ink cloud if he wanted to survive. Ralph decided he needed to reconfigure his normal ink cloud settings. If Ralph were human, he might add texture additives to his paint, some kind of gel medium, or modeling paste, but as much as we want to anthropomorphize Ralph, he doesn’t have the ability to run out to an art store for supplies. No matter how much octopus enthusiasts speculate about their intelligence being beyond our comprehension, Ralph also doesn’t have the wherewithal necessary to earn enough money to complete such a transition, and even if he did, most enthusiasts would concede that Ralph doesn’t have the physical or cerebral capabilities necessary to complete such a transaction. Even if he does, one day, Ralph’s interactions with the clerk might lead to whole bunch of confusion, screaming, and possible violence that would inhibit Ralph’s attempts to get the materials he needs. Ralph’s store of supplies is almost entirely internal, and we add the word almost because some octopuses use tools. For this particular need, however, Ralph has few external resources. He knows he must create a more substantial cloud to fool predators better, because today’s narrow escape was way too close for him. Next time, he decides, he will need to add more mucus to his ink cloud for a better, more convincing self-portrait that we call a pseudomorph. As I wrote in Octopus Nuggets I, the pseudomorph may not be so rich in detail that anyone would confuse it with what Van Gogh left behind, but as long as they’re able to confuse sharks for a necessary second, it will serve its purpose.

Octopus researchers aren’t sure why they edit their RNA, but we have to assume it has something to do with predation, either surviving it or finding nuanced ways to perfect their own. If you’re nowhere near as fascinated with this idea as I am, at this point, you will have to excuse my crush with these cephalopods in the ensuing paragraphs.

An article from Business Insider further describes the difference between DNA and RNA as it applies to editing, by stating, “Editing DNA allows a species to evolve in a manner that provides a more permanent solution for the future survival of the species. When a being edits their RNA, however, they essentially “try out” an adaptation to see if it works. I consider this practice impressive on its face, but imagine how many humans fail to edit their RNA enough to practice the ‘if one thing doesn’t work, try another’ principle.

One other note the authors of this piece add to this subject is that “Unlike a DNA adaptation, RNA adaptations are not hereditary.” Therefore, we can only guess that if an octopus discovers a successful RNA rewrite that could be used as a survival tactic, they would have to teach it to their friends and offspring, or pass it along by whatever means an octopus passes along such information. (Octopuses are notorious loners who don’t communicate with one another well, and they’re often dead before their offspring reach maturation, so I don’t know who they might be teaching.)

A quote from within the article, from a Professor Eli Eisenberg, puts it this way: “You can think of [RNA editing] as spell checking. If you have a word document, and you want to change the information, you take one letter and you replace it with another.”

Research suggests that while humans only have about ten RNA editing sites, octopuses have tens of thousands. Current science is unable to explain why an octopus edits their RNA, or when RNA editing started in the species. If this is the case, I ask current science, how can we determine, with any certitude, that an octopus edits their RNA. I’m sure that they examine the corpses of octopuses and compare them to others, but how can they tell that the octopus edits their RNA themselves? How do they know, with this degree of certitude, that there aren’t so many different strains of octopuses that have a wide variety of different RNA strands? How did they arrive at the different strands? Did they edit them themselves, or did they come equipped with them by another means? This topic fascinates me, but I’m sure an octopus enthusiast, a researcher, and a geneticist can tell how ignorant I am on this subject, and I’m sure these findings are scientifically sound, but I’ve read numerous attempts to study the octopus, and almost all of them characterize the octopus as notoriously difficult to study. Some have described the octopuses’ rebellious attempts to thwart brain study as obnoxious. If that’s the case, then I have to ask if the conclusions they reach are largely theoretical based on these notoriously difficult studies of octopus corpses.

The final answers to my questions might circle us back to Katherine Harmon Courage’s provocative notion that “If we can figure out how the octopus manages its complex feats of cognition, we might be closer to discovering some of the fundamental elements of thought in general –and to developing new ideas about how mental capacity evolved.”

If we are able to do that, Gizmodo.com quotes scientists who suggest we might be able to root out a mutant RNA in our own strands to see if we can edit them in a manner that might aid in our own survival.

We can marvel at the adaptations the octopus is able to make, and as the article illustrates, I will join you in that open-mouthed awe, but do they prove intelligence? They can solve puzzles though, and those who work with octopuses know that if they don’t provide an octopus mental stimuli the octopus gets bored, frustrated, and unruly. Most zoo patrons enjoy the experience of viewing otherwise wild animals, but they also feel sorry for them for being caged up. The latter is often misplaced, in my opinion, because I think most animals enjoy their experience. They no longer have to hunt for food, because they know they’ll receive a feeding at about three o’clock every day. Plus, most of them have never known a wild existence, as they’ve been semi-domesticated their whole lives. The idea that the octopus needs constant mental stimuli and cerebral engagement, even among those who have been semi-domesticated their whole lives, does suggest a level of intelligence beyond most in the animal kingdom, but how much do we glamorize and exaggerate our observances and findings to fit our narratives in the same manner the Vikings of Nordic lore did with theirs centuries ago?

There are a wide variety of reasons the octopus has managed to survive, in various forms, for 330 million years. Is it intelligence, emotional intelligence, or an incredible, almost unprecedented, ability to adapt. All animals have a survival instinct, and they use all the tools at their disposal to achieve it. Some of the tools they have can blow our mind, such as those mentioned above, camouflage techniques, and the ways animals and plants mimic one another for the purpose of defense and predation. To equate those incredible tools to incredible levels intelligence, however, strains credulity at times. The species has survived 330 million years, but the individual octopus dies after five years, and they do not pass knowledge onto their offspring, so how much intelligence can they accrue and pass along?

There is a conceit in the human brain (of the ever-present present tense) that these are the best of times in terms of knowledge, understanding and science, but some scientists concede that we just don’t know what we don’t know yet. We know our level of knowledge is great in the present tense, at least compared to the past, but some part of us knows that the leaps and bounds we’ve achieved will be achieved by leaps and bounds by future researchers and scientists to a degree that future scientists will regard our level of scientific knowledge as almost primitive by comparison. To those future scientists who seek guidance on the idea of further editing RNA, the authors of the Business Insider, David Anderson and Abby Tang suggest that they, “Can learn a thing or two from these cephalopod experts.”