“I have so many ideas rolling around in my head. I have some great ones too,” a man named Kelley told me. “I just need some money to make them work, and I’ve never had any money.” Some of us might laugh at such a foolish notion, and some of us might say, ‘If your ideas are so great, why haven’t you done anything about them?’

Kelley wouldn’t tell me what his ideas were. He avoided answering me when I asked for specifics, and he quickly changed the subject when he saw that I wasn’t going to let it go. He enjoyed my general level of intrigue, because most idea guys don’t even receive that, but my guess is he didn’t want to risk damaging that interest by telling me what his ideas were. I knew why Kelley did that, because I was Kelley on so many occasions, and I saw my listeners’ faces turn to ‘that’s kind of dumb’ disappointment when I told them my ideas. I knew the vulnerability, bordering on fragility, and I also knew what happened when we accidentally gave a cynical, once-bitten hyena one of our ideas. I knew what it felt like when they took a chunk of flesh. What Kelley didn’t know, because he couldn’t, was that I was so into the plight of the idea man that I often waited for them to finish to offer them blind encouragement. Since Kelley didn’t know me, he just assumed that I was one of those who consider it their responsibility to crush idea men at the gate.

“I don’t see it as mean,” former talent judge from the show American Idol, Simon Cowell, once said regarding crushing other peoples’ dreams. “I see it as freeing them from their lifelong dream of being a singer. No one ever told them that they couldn’t sing before. When I tell them, it frees them up to pursue all these other avenues in life.” This isn’t an exact quote, but it is so close that it gives us some idea what Cowell probably dreamed up one night to presumably free himself of the guilt that caused his chronic bouts of insomnia.

“I don’t see it as mean,” former talent judge from the show American Idol, Simon Cowell, once said regarding crushing other peoples’ dreams. “I see it as freeing them from their lifelong dream of being a singer. No one ever told them that they couldn’t sing before. When I tell them, it frees them up to pursue all these other avenues in life.” This isn’t an exact quote, but it is so close that it gives us some idea what Cowell probably dreamed up one night to presumably free himself of the guilt that caused his chronic bouts of insomnia.

All these years later, we learn that that wasn’t the real Simon Cowell. Simon Cowell, we learn, wasn’t a mean man. He had to learn how to be one. A TV executive, named Mike Darnell, states that “In all the other shows before him, everyone was polite and nice, and I knew [crushing people’s dreams in the meanest way possible] was going to be [his] thing. Simon, to his credit, was willing to do anything.” Simon Cowell had to learn how to be a mean character if he wanted American Idol to be successful, and “He was willing to do anything”, including absolutely crush the dreams of the participants on the show to achieve his own fame and fortune. Is this supposed to vindicate the guy? Not only could I not be that guy, no matter what rewards awaited me, I couldn’t even watch his show. I watched it once, because everyone told me it was so fantastic, but I couldn’t bear to watch the glimmer of hope fall out of the eyes of my fellow dreamers when Simon Cowell’s mean-spirited character laid them out.

I don’t know if I’m the opposite of Simon Cowell, when it comes to idea men floating their dreams to me, but I approach their pitch from an ‘I don’t know what the hell I’m talking about’ mindset. That mindset was born the day Beanie Babies hit our store shelves. The idea that we had a line that stretched from our hotel entrance to the gift shop, where they were sold, set my beliefs about the American consumer back by about ten years. If I were a toy executive, listening to the idea men pitch their Beanie Baby idea to me, I probably would’ve said something along the line of, “I like them, they’re well done, cute, and all that, but if we buy your product, we’re not going to devote much of our resources to their manufacturing, and we’re not going to devote much to their marketing either. We already have a certain percentage of our budget devoted to the teddy bear market, and I don’t see how these products demand anything beyond our typical financial devotion to a product.” As we all know, this is but one bit of evidence that ‘I don’t know what the hell I’m talking about’ when it comes to the desires of the typical consumer, or ideas in general.

I don’t know if I’m the opposite of Simon Cowell, when it comes to idea men floating their dreams to me, but I approach their pitch from an ‘I don’t know what the hell I’m talking about’ mindset. That mindset was born the day Beanie Babies hit our store shelves. The idea that we had a line that stretched from our hotel entrance to the gift shop, where they were sold, set my beliefs about the American consumer back by about ten years. If I were a toy executive, listening to the idea men pitch their Beanie Baby idea to me, I probably would’ve said something along the line of, “I like them, they’re well done, cute, and all that, but if we buy your product, we’re not going to devote much of our resources to their manufacturing, and we’re not going to devote much to their marketing either. We already have a certain percentage of our budget devoted to the teddy bear market, and I don’t see how these products demand anything beyond our typical financial devotion to a product.” As we all know, this is but one bit of evidence that ‘I don’t know what the hell I’m talking about’ when it comes to the desires of the typical consumer, or ideas in general.

Simon Cowell, I suspect, also “Learned how to be mean” to establish his bona fides as an authoritative expert, so the show’s organizers front-loaded it with talent that couldn’t sing. I could see that, you could see that, and Simon Cowell could see it too, and he was so frank in his assessments that some could mistake it as cruel. “Hey, he needs to hear that, because he is bad,” audience members said while they were laughing. Simon Cowell, his handlers, and the corporate execs obviously did their research on how to create a character that fed into the American definition of an authoritative expert. If they were correct, and the rating show that they were, the American definition of the man who holds the keys to the kingdom is a mean man. We see this in our movies and cartoons, and it’s become an affixed image in our brains. If the American public were going to take Simon Cowell seriously, he was going to have to be theatrical when informing those who lost in first round, and he would have to remain unconcerned with their feelings, because being nice and polite is boring, and it doesn’t feed into the American definition of an authoritative expert.

We might think that an idea man, listening to the ideas of another man, would want to avoid every trait of the Simon Cowell character. We might think that after getting ripped apart by their own hyenas and jackals that they would be more sympathetic and empathetic that the average man to the tumultuous path of the idea. We might think they would want to be the confidant, the facilitator, or the one person the idea man can count on to be supportive. We might even think that an idea men would strive to create mutual appreciation relationships to treat the ideas of idea men the way they want theirs to be treated. In my relatively limited experience, they do the opposite. They skeptically diminish, deride, and dismiss all others’ ideas to essentially clear the deck of ideas, so theirs is the only one left standing. It’s a “My idea might be flawed, but it’s not as flawed as yours” methodology of propping their ideas up by pushing everyone else’s down.

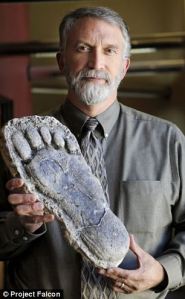

These clear-the-decks idea men share many characteristics with the Bigfoot experts. If you’ve ever watched an exploration of the Bigfoot universe, you’ve been inundated with the experts in this field of cryptozoology. As with idea men, the breadth of the various pitches they offer to establish their expertise often devolves to tearing down the competition. One expert, we’ll call him Tom, claims to be the Big Foot expert. Tom claims to have had numerous harrowing encounters. He provides details of those encounters (cue the actor in the hairy suit for the reenactment), and he shows us evidence of those encounters, such as the plaster cast footprint, a ripped tent, or damaged car to show the wrath of the Bigfoot. Based on his numerous experiences, the evidence, and his particularly charismatic and convincing presentation, Tom is widely regarded as the Big Foot expert. This bothers Dick, the lesser-known but up-and-coming expert in this field. We might think Dick would try to rival Tom’s experiences with his own, but he chooses to try to poke holes in Toms’ stories, until it’s fairly obvious that he’s trying to destroy Tom’s legacy in the field. Dick claims that true cryptozoologists, with a Bigfoot focus, know Tom’s claims are “dubious to say the least.” Dick tries to establish his bona fides in the Big Foot community by scrutinizing Tom’s claims, as if they’re not rooted in the scientific method. Dick then lists some of his own credentials, his theories, and his firsthand experiences, but the breadth of his presentation focuses on bringing Tom, the foremost expert in the field, down. Harry refutes Tom and Dick’s claims with a “If this is true then that would have to be true too” prosecutorial breakdown that leads the audience to believe that Tom and Dick’s presentations are basically nonsense. Thus, Harry claims to be the “real expert” by a last man standing process of elimination. In the end, no parties produce irrefutable information, because there isn’t any, and as a result the experts, like the idea men, end up dueling over the circumstantial evidence they gathered.

These clear-the-decks idea men share many characteristics with the Bigfoot experts. If you’ve ever watched an exploration of the Bigfoot universe, you’ve been inundated with the experts in this field of cryptozoology. As with idea men, the breadth of the various pitches they offer to establish their expertise often devolves to tearing down the competition. One expert, we’ll call him Tom, claims to be the Big Foot expert. Tom claims to have had numerous harrowing encounters. He provides details of those encounters (cue the actor in the hairy suit for the reenactment), and he shows us evidence of those encounters, such as the plaster cast footprint, a ripped tent, or damaged car to show the wrath of the Bigfoot. Based on his numerous experiences, the evidence, and his particularly charismatic and convincing presentation, Tom is widely regarded as the Big Foot expert. This bothers Dick, the lesser-known but up-and-coming expert in this field. We might think Dick would try to rival Tom’s experiences with his own, but he chooses to try to poke holes in Toms’ stories, until it’s fairly obvious that he’s trying to destroy Tom’s legacy in the field. Dick claims that true cryptozoologists, with a Bigfoot focus, know Tom’s claims are “dubious to say the least.” Dick tries to establish his bona fides in the Big Foot community by scrutinizing Tom’s claims, as if they’re not rooted in the scientific method. Dick then lists some of his own credentials, his theories, and his firsthand experiences, but the breadth of his presentation focuses on bringing Tom, the foremost expert in the field, down. Harry refutes Tom and Dick’s claims with a “If this is true then that would have to be true too” prosecutorial breakdown that leads the audience to believe that Tom and Dick’s presentations are basically nonsense. Thus, Harry claims to be the “real expert” by a last man standing process of elimination. In the end, no parties produce irrefutable information, because there isn’t any, and as a result the experts, like the idea men, end up dueling over the circumstantial evidence they gathered.

Our ideas might be flawed. We might not be as funny as we think, we might not know how to sing, or we might be able to write well, but our dreams and ideas secretly make us feel special. They’re what we think separates us from the pack. I could see this in Kelley’s eyes. He thought his very general pitch was a declaration that he wasn’t a low-level, blue-collar worker like me. He was (trumpet’s blare) an idea man, and the only reason he wasn’t there yet was he didn’t have any money. We all think if we just had a few thousand dollars, or the right connection to that person in the know, or that big break that the man had, everyone would know that we’re not just idea men. We’re the real deal, not like Anthony over there, who’s just a dreamer. “You have to know someone to get somewhere,” we frustrated types say when we don’t get where we need to be. “It’s all a game, and you have to know how to play it to get there.”

The idea that we’re none of us are who you think we are, “a common blue-collar worker like you,” and we’re actually a lot more special than anyone knows, was brilliantly captured on the classic show Taxi. No one in the blue-collar dispatch area, on that show, was just a cab driver: one driver was also boxer who just drove for the money, another an actor, a receptionist in an art gallery, and the last was a guy just working there to put himself through college. After each character went through their real roles in life, the character Alex Rieger declared, “It looks like I’m the only taxi driver here.” Their dreams, our dreams, are our way of getting through the rigamarole of the daily life of the worker, and the general tedium of life. They are our reason to wake up in the morning, and the reason we keep going through the routines of life, but some of the times our ideas aren’t as great as we think they are, and we’re afraid of meeting that Simon Cowell-type who will not only tell us the truth, but humiliate and emasculate us for ever dreaming in the first place. Simon Cowell-types can say that their goal is to free us from unreasonable ideas, aspirations, and dreams, but we all know that they enjoy laying out the harsh realities of life.

Did you ever have a dream? We all did, when we were dumb and stupid in our twenties. Our dreams may have been delusional and a “total waste of time”, but they were all ours. Did someone come along and deliver a harsh dose of reality to you? Did you, now well-schooled in reality thanks to those who cared about you and couldn’t bear to see you waste your time, dispense this knowledge to another? Did it feel good? Okay, maybe not good in the literal sense, but how about justified? Some people, and we all know who they are, love to crush dreamers with a reality hammer, because they’re more than happy to help someone else in this regard.

“The trick is to hold onto your young dreams.” –George Meredith

Dreams are largely a refuge of the young. Talk to any kid, and you’ll hear about their dreams, all of them. If you fear that your kid might be headed down a delusional and a “total waste of time” path that you hate to see them spend one second pursuing it, wait a second, don’t say a word, wait, and be patient. They’ll have another, totally different dream tomorrow. Unless someone comes along to effectively crush our dreams, we’re still in this dream-like state in our twenties. The only problem is we don’t have any money, no connections, and absolutely no path to seeing our ideas and dreams to fruition.

If it’s true that our brains don’t fully formulate until we’re twenty-six-years-old, the twenties are our last vestiges of youth, but we’re old enough and mature enough to start seeking concrete paths for our youthful dreams. The thirties are a rough time for dreams, as the faint light at the end of the tunnel begins to fade in the decade-plus years spent in the workplace, but we’re also not so old, yet, that we consider those dreams foolish notions. That usually happens in our forties, as we begin to whittle away at the idea pool to sort out the outlandish, never-gonna-happen dreams, and we become more realistic. Few of our dreams last into our sixties, as we begin to realize that we should’ve either focused our mind more on the more realistic dreams we had or given up on all of it sooner and focused on something that mattered so much more.

This general, and relative lifecycle of dreamers can be artificially altered and disrupted by dream crushers, and as I write, they think they’re doing a service to their fellow man. They don’t consider the idea that we all think different, and some of us can walk and chew bubble gum at the same time. When I hear a dream crusher brag about injecting a dose of reality in another’s head, and they always do with some measure of pride, I ask them, “Why would you do something like that?” When I ask that in an emotionally charged manner, I can see, in the manner in which they answer, that that was the last question they expected from us, or anyone else for that matter. You can also see that they failed to consider the other side of their advice, or that that person might just be different than them.

“You heard their idea. It was ludicrous, and a total waste of time. Someone had to say something. I think it was for their own good that they hear that,” they say. They also add some variation of, “Better they hear it from me than someone who doesn’t care about them.”

“Okay,” I said, “but did it benefit them? I think we can both agree that he’s an upstanding man, good father, good husband, quality friend and employee,”

“From what we know, yeah.”

“And most of the time he “wastes” pursuing a dream “that was never going to happen,” was done with whatever free time he had left. If all that was true, and as you say from what we know it was, how did your dose of reality benefit him?”

“He was just wasting so much time and energy on it. I couldn’t bear to watch it anymore. Someone had to tell him the truth before he got his heart broken.”

“So, you broke his heart to prevent him from getting his heart broken? While you were smashing, did you ever consider the idea that some portion of the happy-go-lucky, unflappable personality that you and I know and love was based on those outlandish dreams and unrealistic goals? What if he believed you, or you made some kind of dent? What if he stops pursuing his lifelong dream, based on what you said? How would you feel if he come back to us as hopeless and cynical as you are? Would you feel vindicated, or would you realize that he’s probably not going to tell you, or anyone else, what his dreams are anymore, if he continues to pursue them. And what if he doesn’t? What if he admires and respects your opinion so much that he realizes that pursuing his dream was a waste of time and energy, and he just gives up on them? It’s possible that he might come back to us a little more unhappy than he was yesterday.”