“Neptune was the first planet to be discovered through mathematical equations, as opposed to astronomical observations.”

“Perturbing body,” were the words French astronomer Alex Bouvard wrote to set off a firestorm in astronomical, physicist, and mathematician societies throughout the world. He wrote that to explain why his published predictions on the orbit of Uranus were wrong. “How else can we explain it?” Bouvard probably said. Bouvard’s methodical and careful approach to observations were such that when he made official declarations, people listened. When in 1821, he hypothesized that an eighth planet must be responsible for the irregularities in Uranus’ orbit, it opened the window for the discovery of what we now as Neptune.

Some believed in Bouvard’s perturbing body theory, some did not. Some argued that Uranus’ irregular orbit proved that Isaac Newton’s theories on gravitation and motion, on which Bouvard made his initial predictions, were just wrong. Astronomer John Couch Adams wasn’t buying it. He believed “he could use [Bouvard’s] observed data on Uranus, and utilizing nothing more than Newton’s law of gravitation, deduce the mass, position and orbit of the perturbing body.” After four years spent studying Uranus’ orbit, in conjunction with this theory, Adams submitted his findings in 1845. Yet, for some reason, he didn’t respond to official queries for detailed calculations of his findings. Had he responded quickly, Adams may have cemented his role in history as the lone individual responsible for theoretically projecting that Bouvard’s “perturbing force” was, in fact, another planet. “Some suspect that Adam’s failure to respond in a timely manner may have been due to his general nervousness, procrastination and disorganization.”

Some believed in Bouvard’s perturbing body theory, some did not. Some argued that Uranus’ irregular orbit proved that Isaac Newton’s theories on gravitation and motion, on which Bouvard made his initial predictions, were just wrong. Astronomer John Couch Adams wasn’t buying it. He believed “he could use [Bouvard’s] observed data on Uranus, and utilizing nothing more than Newton’s law of gravitation, deduce the mass, position and orbit of the perturbing body.” After four years spent studying Uranus’ orbit, in conjunction with this theory, Adams submitted his findings in 1845. Yet, for some reason, he didn’t respond to official queries for detailed calculations of his findings. Had he responded quickly, Adams may have cemented his role in history as the lone individual responsible for theoretically projecting that Bouvard’s “perturbing force” was, in fact, another planet. “Some suspect that Adam’s failure to respond in a timely manner may have been due to his general nervousness, procrastination and disorganization.”

It’s also possible that Adams may not have had the detailed calculations, at the time, that would withstand scrutiny. Prior to the call for detailed calculations, Adams was elected fellow of his college based on the idea that he would be the one to answer the questions about the perturbing body theory. We can only speculate that he might have enjoyed that life so much that he didn’t want to risk putting that on the line. In the four years he spent studying the issue, we can assume he gathered a team of students and other assistants to help him formulate calculations and fact-check the findings. We can also guess that Adams’ own people found problems with the theoretical guesses they reached. If he officially submitted those detailed calculations to an observatory when they were called for, and they couldn’t observe the planet, based on his calculations, it might have damaged his reputation and standing in his community. Adams eventually submitted his findings, and they were twelve degrees off.

Whether he was studying Uranus’ orbit and the idea of a perturbing body at the same time as Adams, or he piggy-backed on Adam’s findings to support his own calculations, Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier immediately responded to calls for detailed calculations. Le Verrier sent his coordinates to Berlin Observatory astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle’s inquiries, and Galle confirmed the existence of the planet on September 23, 1846. Galle confirmed Le Verrier’s detailed calculations, but added that Le Verrier was one degree off. [Note: The international astronomy community eventually decided to settle the international dispute by giving credit to both the British Adams and the French Urbain for Neptune’s discovery, even though Adams unofficially discovered it first.] Astronomy.com also states that “Adams [eventually] completed his calculations first, but Le Verrier published first. Le Verrier’s calculations were also more accurate.” The lesson here for kids is when the international community approaches you for detailed calculations to support your astronomical findings make sure you either respond immediately, or maybe you should have your detailed calculations ready before declaring your findings.

Whether he was studying Uranus’ orbit and the idea of a perturbing body at the same time as Adams, or he piggy-backed on Adam’s findings to support his own calculations, Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier immediately responded to calls for detailed calculations. Le Verrier sent his coordinates to Berlin Observatory astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle’s inquiries, and Galle confirmed the existence of the planet on September 23, 1846. Galle confirmed Le Verrier’s detailed calculations, but added that Le Verrier was one degree off. [Note: The international astronomy community eventually decided to settle the international dispute by giving credit to both the British Adams and the French Urbain for Neptune’s discovery, even though Adams unofficially discovered it first.] Astronomy.com also states that “Adams [eventually] completed his calculations first, but Le Verrier published first. Le Verrier’s calculations were also more accurate.” The lesson here for kids is when the international community approaches you for detailed calculations to support your astronomical findings make sure you either respond immediately, or maybe you should have your detailed calculations ready before declaring your findings.

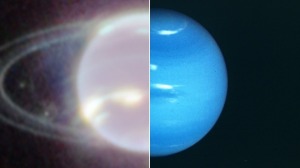

Uranus was discovered in 1781, Bouvard declared that its orbit was irregular in 1821, and Le Verrier finalized all speculation regarding the perturbing force by declaring it was a planet providing that perturbing force twenty-five years later in 1846, after Bouvard’s death. We have to suspect that almost all of the astronomers, physicists, and mathematicians knew that the perturbing force had to be a planet, but they couldn’t find it. Neptune is not visible by the naked eye, and this, coupled with the technological limitations they had at the time, forced the brightest minds in astronomy, physics, and mathematics to base their theoretical predictions and findings on the celestial mechanics of Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton theories, and this idea that the entire universe existed on universally accepted mathematical principles.

I find it impressive that a man, any man, could take a supposition, such as the perturbing body theory, and mathematically project that due to the irregular movements of Uranus’ that the perturbing body has to be located right there and be one degree off. We can only guess that in the intervening twenty-four to twenty-five years, there were hundreds of guesses submitted to observatories, and they were all wrong.

Were all of those theoretical guesses wrong, or were they, as P Andrew Karam, at Encyclopedia.com states, simply the result of bad timing? “The discovery of Neptune proved more a remarkable coincidence than a testimony to mathematical prowess.

“Leverrier’s and Adams’s solutions for Neptune’s orbit were incorrect. They both assumed Neptune to lie further from the sun than it actually does, leading, in turn, to erroneous calculations of Neptune’s actual orbit. In fact, while the calculated position was correct, had the search taken place even a year earlier or later, Neptune would not have been discovered so readily and both Leverrier and Adams might well be unknown today except as historical footnotes. These inaccuracies are best summarized by a comment made by a Scientific American editor:”

“Leverrier’s planet in the end matched neither the orbit, size, location or any other significant characteristic of the planet Neptune, but he still garners most of the credit for discovering it.”

“It is also worth noting that, after Neptune’s mass and orbit were calculated, they turned out to be insufficient to account for all of the discrepancies in Uranus’s motion and, in turn, Neptune appeared to have discrepancies in its orbit. This spurred the searches culminating in Pluto’s discovery in 1930. However, since Pluto is not large enough to cause Neptune and Uranus to diverge from their orbits, some astronomers speculated the existence of still more planets beyond Pluto. Hence, Pluto’s discovery, too, seems to be more remarkable coincidence than testimony to mathematical prowess. More recent work suggests that these orbital discrepancies do not actually exist and are due instead to plotting the planets’ positions on the inexact star charts that existed until recently.”

The two of them got lucky in Karam’s words. They made 19th Century errors that we can now fact-check with our modern technology, and we can now say that they timed their findings at a most opportune time in Neptune’s orbit. Yet, whatever “remarkable coincidences” occurred, it turns out Leverrier’s “calculated position [proved] correct”.

The two of them got lucky in Karam’s words. They made 19th Century errors that we can now fact-check with our modern technology, and we can now say that they timed their findings at a most opportune time in Neptune’s orbit. Yet, whatever “remarkable coincidences” occurred, it turns out Leverrier’s “calculated position [proved] correct”.

“The remarkable coincidences” answers the question why so many previous theoretical submissions were incorrect, rejected, or couldn’t be observed by observatories and thus verified between Bouvard’s initial theory in 1821 and Leverrier’s detailed calculations of the positioning of the planet later named Neptune.

As with any story of this type, some of us wonder what happened between the lines? Have you ever been so obsessed with something that you couldn’t function on a normal human level? Have you ever been so obsessed with something that you didn’t enjoy food, drink, or any of the other fundamental joys of life the way you did before? Have you ever been so obsessed that you couldn’t sleep at night, and routine, mundane conversations with your friends seemed so routine and mundane that you can’t bear them, until you resolve the one problem that haunts you. How many accomplished individuals in their respective fields sacrificed dating, marrying, and having a family to their focus their existence on being the one to find the answer to the perturbing body theory? We can talk about fame, and fortune, and all that, but if you’re genuinely obsessed, you reach a tipping point where those things become nothing more than a byproduct to working through the question to find the answer on your own. In instances such as these, even a level of historical fame pales in comparison to the personal satisfaction we feel by finding the answer.

Whatever the case was, we can comfortably guess that Adams and Le Verrier didn’t submit the first predictions. We can find fault in Le Verrier’s projections, but we should remember that he was providing an educated guess that a planet one billion miles away from Uranus, and 2.7 billion miles away from him existed. The observatory asked him for detailed calculations, he provided them, and the observatory used those calculations to spot Neptune. I consider that a point blank exclamation mark at the end of this discussion.

Yet, whenever we discuss the idea that .25% of the population, or one in 400, are geniuses, and we publicly marvel at their accomplishments, some ninny comes along and drops the ever-annoying, “It would’ve eventually been discovered by someone, somewhere.” When we express exhaustion, they add, “What? It’s a planet, a planet that is roughly four times larger than Earth. Someone would’ve eventually spotted it.”

As much as we loathe such dismissals, it appears to be true in this case. If P Andrew Karam is correct, and we have no reason to doubt him, Adams and Leverrier were the first to submit right place, right time predictions that due to “a remarkable coincidence” could be verified due to the timing of their submissions.

It also bothers those of us who enjoy marveling at genius to hear things like, “Some guys are just smarter than others. I know some smart guys who say some smart things.” That’s true too, of course, but some are geniuses, and some of us love nothing more than dissecting, refuting, and demystifying the notions of their genius. Were John Couch Adams and Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier geniuses who figured something out that no one else could, or were they right-time, right place opportunists? No matter what Karam writes about their errors, he admits the “calculated position was correct”.

Le Verrier’s calculated position was also derived without the benefit of James Webb or Hubble telescopes, and he and Adams did not know the nuclear-powered space probes that could confirm theoretical guesses on the molecular composition of the lakes on Saturn’s moon Titan. They also did not have the advantage provided by Voyager Spacecraft visits, of course. They had Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravitation, the idea of celestial mechanics from Johannes Kepler, some comparatively archaic technology, and a pencil and paper.

With our modern technology, we can now correct the mistakes of the past. This is the way it should be, of course, but we should refrain from diminishing past accomplishments or inherently claiming superior intelligence now. We might know more now thanks to the brilliance of our greatest technological toys, but most of us had nothing to do with building that technology. We’re just the beneficiaries of it. We now have the advantage of all of these marvelous gadgets and tools at our disposal to fact-check prior “geniuses”, but does that mean that the brilliant minds of the past weren’t geniuses? We can talk about how some of the theories don’t stand up, but think about how many physicists, astronomers, mathematicians, and general theorists of yesteryear developed theories, without the advantage of the accumulated knowledge we’ve gathered since, that do?

Some of the geniuses of yesteryear turned out to be wrong, of course, and some of them were right-place, right-time opportunists who discovered things first, but before you say “Someone, somewhere would’ve discovered it” remember the guys who mathematically predicted the existence of Neptune, probably road a horse to work on a dirt road, if they were lucky enough and rich enough to own a horse, and their definition of the heart of the city was often just a bunch of wooden store fronts, like the recreations we see on the old HBO show Deadwood. Most of what these 19th century astronomers and mathematicians saw in the nighttime sky is what we can see by stepping outside and looking up into the sky. They had some technological assistance back then, in the form of relatively weak telescopes, and some theorize that astronomers, like Galileo Galilei in 1613, Jerome Lalande in 1795, and John Herschel in 1830 may have used it to spot Neptune first, but they didn’t know they were seeing a planet, because their telescopes were not powerful enough for them to know that. Those of us who write articles about such topics and the geniuses who made ingenious discoveries or theories that proved slightly incorrect or somewhat flawed should asterisk our critiques by saying, “I am smart. No, really I am, really, really smart, but as ingenious as I am, I don’t know if I could’ve done what they did with the primitive technology they had, primitive when compared to ours. So, before I go about correcting and critiquing their findings with the technology I have at my disposal, thanks to those who developed it for me, I’d like to say how impressive it is that they came so close that it’s impressive that they did what they did with what they had.”