“You have some killer calves bra,” Gunther, the gym rat, said at the gym. I can’t remember if I said, ‘thanks’ or ‘SECURITY!’ but Gunther (pronounced Goon~thur as opposed to Gun~thur), sensed my awkwardness. “Seriously bro, you’ve done some good work. I’m thinking of getting mine done. Gonna get me some pumped up calves.” After some back and forth, he confirmed that meant he was thinking about having calf implants surgically inserted into his legs. “I do all of the calf raises, the farmer’s walk, the Box jumps, and jumping jacks, and look at me, I got nothing down there bro. Look at those puny things! Look at them compared to my thighs, they’re incongruent!”

You ever meet this guy, a guy who appears to have it all, and he obsesses over something so trivial that if I told you about it, you might say, “He was joking. He had to be.” I didn’t bother breaking it down with him to see if he was joking, because why would I? I was there, and I knew how serious he was. I did wonder what motivated this obvious obsession with anatomical perfection, and I wondered how deep it went. Did he think everyone was staring at his “puny calves” the minute he walked into a room? Did he refuse to wear shorts, to avoid exposing his humiliation? Did he blame his parents for giving him such awful genes “down there”. I wondered if he thought that by attaining “pumped up” calves, even if by artificial means, that he might be able to improve his perception by eradicating the inadequacies below his leg pits.

You ever meet this guy, a guy who appears to have it all, and he obsesses over something so trivial that if I told you about it, you might say, “He was joking. He had to be.” I didn’t bother breaking it down with him to see if he was joking, because why would I? I was there, and I knew how serious he was. I did wonder what motivated this obvious obsession with anatomical perfection, and I wondered how deep it went. Did he think everyone was staring at his “puny calves” the minute he walked into a room? Did he refuse to wear shorts, to avoid exposing his humiliation? Did he blame his parents for giving him such awful genes “down there”. I wondered if he thought that by attaining “pumped up” calves, even if by artificial means, that he might be able to improve his perception by eradicating the inadequacies below his leg pits.

“Are you looking to get into a pageant?” I asked.

“First of all, they’re not called pageants,” he said. “They’re called bodybuilding competitions. And no, I’m not looking for any of that. I just think it’s unfair that I work ten to twenty times harder than people like you, no offense, and I get no results.”

Gunther, the gym guy, had so many admirable, and I’ll say it, enviable traits that if he commissioned a poll of a thousand casual observers, my bet is one in a thousand might notice his “puny calves”. If Gunther were asked to predict the outcome of that poll, however, he would probably predict that that figure to be somewhere around 999 out of a thousand who spot them. “How could they miss them?” he might ask.

I told him that if he hadn’t pointed them out to me, I never would’ve noticed them, and I added, “I doubt that anyone else would either.” He acknowledged that and waved it off, basically admitting that he kind of knew it was his issue.

The idea that he moisturized his skin was obvious, as was the idea that he used a wide variety of hair products to color and treat his hair. Gunther, the gym rat, worked hard to perfect every element of his physical presentation, and that included achieving what bodybuilders call the X-frame: broad shoulders, a narrow waist, and well-developed thighs. This shape creates what experts call “a striking visual taper, proportion, balance, and a symmetrical emphasis that creates a harmonious and powerful aesthetic that all gym rats strive to achieve.” Yet, Gunther couldn’t do anything about his “puny calves”, so he contemplated letting a surgeon do it for him, because “it wasn’t fair” that he couldn’t.

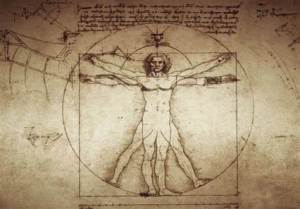

My guess is if another perfectionist, Leonardo da Vinci, decided to give his Vitruvian Man “puny calves”, after studying the ideal proportions of the human form, none of us would notice. Da Vinci would, and Gunther would, because they were far more concerned with achieving anatomical perfection.

We can all understand and appreciate da Vinci’s drive to achieve an artistic representation of perfection, in other words, but there was something almost obnoxious about Gunther’s psychological drive to fix his “incongruity” that when he used that word it stuck with me. I never heard anyone, in the bodybuilding universe, or anywhere else, complain about their incongruity. It was almost as if he thought if he used a different, more creative term, it might exert some special kind of shame for those muscles, and they might finally respond to all of his efforts. And he did speak of these muscles as if they were disembodied entities. Then, he concluded his scorn by saying if they didn’t respond to his wishes, he would find someone (a surgeon) who would.

I don’t know if Gunther eventually purchased that unnecessary, cosmetic surgery, as that would be the last conversation I had with him. If he bought it, I wonder if it helped him feel more congruent. Our immediate guess would be no, as cosmetics only resolve superficial issues. That’s so true it’s almost a fact, but fixing what ails us, or what we think ails us, can have a placebo effect that helps us feel better about ourselves and solves so many other issues. As my science teacher once told me, our initial guesses are often correct, and my initial guess was that Gunther’s feelings of incongruence were so pervasive that the day, the week, or the month after that surgery, he’d find some other incongruity he considered a roadblock to happiness.

***

Are we happy? Are we happier than we’ve ever been, right here, right now? We’re not as happy as we’ve been, but we’re pretty sure that once forces beyond our control align, we’re going to be happier in the future.

It’s difficult to avoid taking things for granted, but how many of us consider physical congruence an essential element of happiness? Before laughing that off as silly, we need to consider that physical beauty can lead to more confidence, and confidence can lead to greater happiness, and if the congruity of our face equates to beauty, how happy can we be with a big nose? We can get a nose job, but the minute that’s done, it makes our earlobes look flappy. If we lop those off, how congruent are our lips now, and what about our “too narrow” eyes? And, if we have too much forehead, how do we fix that? We often hear that we must accept what our Creator has given or withheld, but to what extent can absolute congruence align with our identity and eventually foster happiness?

We accuse one another of being superficial when we obsess over the physical beauty of others, but what would they think of us if they knew how superficial we are with our own? Good friends and a great family can provide an excellent support system, and making a boatload of money can help even the scales if we love what we’re doing for a living, but none of these elements of life last forever in intangible and tangible ways. Beauty doesn’t last forever either, of course, and we all know that, but instead of appreciating everything we have while we have it, we obsess over the qualities that prevent us from achieving our definition of perfection.

I know this makes no sense to the healthy, but we should all take a moment to focus our mind’s eye internally, and appreciate how this incredibly efficient machine that we call our body, operates. We’re not talking about the big guys (heart, liver, lungs) that we all know, but the tiny mechanisms in our systems, the cogs, cranks, chains, and linkages that work in conjunction to keep us healthy and happy, because their quiet efficiencies don’t operate at optimum levels forever. And what’s the difference between internal congruence and superficial? Gunther probably wouldn’t even notice his calves if he had trouble breathing, he had heart problems, or some other internal incongruence that cried out for medical attention. His concerns with his calves were as a result of the luxury afforded to those who have achieved so many levels of optimum efficiency that they have to work their way down the list to find one that isn’t.

We’re talking about physical congruence here. We’re talking about how we should factor physical congruence into our huge, multifaceted happiness puzzle. We all know about how reducing stress and achieving emotional stability can lead to happiness, and we’ve all read how diet and exercise can affect mood stability and a general sense of satisfaction, but how many of us look down at our toes and thank our Creator for giving us foot appendages that grew in a congruent manner to provide the typical comfort we enjoy while standing, walking, or just fitting comfortably into a pair of socks?

***

Don Christie had a middle toe that grew too long for the comfort inherent in congruence. An elongated toe might not generate much sympathy from us because, “It’s a long toe! Who cares?” Compared to a person born with a physical abnormality on the face, or any of the truly sad stories we hear about what babies in prenatal units are forced to endure, it’s tough to do anything more than raise an eyebrow at an otherwise healthy man complaining about an abnormally long toe.

Don Christie had a middle toe that grew too long for the comfort inherent in congruence. An elongated toe might not generate much sympathy from us because, “It’s a long toe! Who cares?” Compared to a person born with a physical abnormality on the face, or any of the truly sad stories we hear about what babies in prenatal units are forced to endure, it’s tough to do anything more than raise an eyebrow at an otherwise healthy man complaining about an abnormally long toe.

Don’s point was that that toe has affected his life in ways most of us take for granted. In order to find comfort standing and walking, Don has had to purchase shoes one size too large to accommodate the space that elongated toe requires. The toe and the shoes he requires, affect his gait pattern, and he has learned to give that toe some slack when he pulls his socks on. It was an annoying attribute when he was a child that grew to a frustration in adulthood, and it’s become a real painful problem, at times, in his senior years. Did it affect his overall sense of happiness? “A little bit, in the ways a toe can affect a day. I’ve adapted, of course, but every once in a while, it becomes a real, painful problem.”

“If it’s that painful, or that big of a problem, why doesn’t he just have a surgeon lop the elongated portion of it off?” That falls under the “easy answer” umbrella, and the “easier said than done” one. That answer isn’t wrong, of course, but it’s still a toe. It’s an annoying toe at times, and it can prove painful, but it’s still his toe, and he’d obviously much rather deal with it than lop off part of his toe.

***

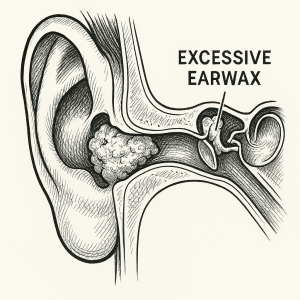

Do your ears produce enough wax or too much? The incredibly complex and largely efficient machine we call the human body effectively clears out most excess wax most of the time, but some unlucky few experience a buildup that can lead to an annoying itch, tinnitus, and in some cases, vertigo that can significantly alter an otherwise pleasant Tuesday in June.

Do your ears produce enough wax or too much? The incredibly complex and largely efficient machine we call the human body effectively clears out most excess wax most of the time, but some unlucky few experience a buildup that can lead to an annoying itch, tinnitus, and in some cases, vertigo that can significantly alter an otherwise pleasant Tuesday in June.

Jack Radamacher was never what we would call a happy person, but he wasn’t miserable, until he started experiencing some hearing loss, a “muffled” sound, and occasional spells of dizziness. The latter was especially concerning to him, and it led him to experience what he considered one of the worst words in the English dictionary, dependent.

“I’d rather die than be dependent on others,” he often said as a younger man, and now, here he was. He didn’t need an arm to hold onto most of the time, but he never knew when a dizzy spell would hit. Prior to his visit to the ear, nose and throat doctor, Jack attributed his hearing loss, and those muffled sounds, to working in a loud machine shop for thirty-eight-years and his age, because he never heard that sometimes the ears neglect to clear out excess wax. Not only did he learn that some ears forget to clear excess wax, he learned that the muffled sounds and dizzy spells he experienced weren’t all age-related.

After the doctor went about cleaning his ears of excessive buildup, Jack experienced what was for him, a revelation.

“I feel cured!” he said when his sense of balance returned, and he no longer experienced muffled sounds. He experienced an odd sense of liberation that led to a greater sense of happiness, until the buildup began again weeks later. When it happened again, he learned about ear wax candles. No one, not even Jack himself, trusted him to do this himself. “The flames generated by the candle can get a little out of control,” his daughter-in-law warned him. So, he was somewhat still dependent on others, but he accepted that if it meant that he could “cure” himself at home on such a regular basis that he achieved a better quality of life as a result.

***

Do you have enough cushion to provide cushion? Some don’t, and we love going after them. “Gil, you got no butt!” we said with laughter. Gil knew that, and he’s known it his whole adult life. It’s why he carries a cushion to the employee cafeteria every day for lunch. “Those chairs are just so uncomfortable,” he said when we ask him about it.

Do you have enough cushion to provide cushion? Some don’t, and we love going after them. “Gil, you got no butt!” we said with laughter. Gil knew that, and he’s known it his whole adult life. It’s why he carries a cushion to the employee cafeteria every day for lunch. “Those chairs are just so uncomfortable,” he said when we ask him about it.

“Huh, I never noticed how uncomfortable these chairs were,” we said.

“Of course you didn’t,” Gil said in a dismissive manner, “because you have cushion back there.”

We called him “No butt Gil” and one person added, “He’s got back. A long ass back,” but it wasn’t a source of daily conversation.

So, when Gil said that about our biological cushions, seemingly out of nowhere, we didn’t know what he was talking about, until we thought about why he thought the cheap, plastic chairs were so uncomfortable, why he brought that cushion to lunch every day, why he had to wear suspenders, and how he always complained about lower back pain.

Gil thought the jokes were as funny as we did, but the fact remained that Gil had a physical incongruence that diminished his quality of life to some degree. Those of us who have never met a Gil, never placed the sensory delight of comfortable sitting in our happiness equation, because we never considered how the quantity or quality of bun could affect us after a hard day at work where sitting in a relatively comfortable chair provides a reward at the end of the day. Even sitting in cheap, plastic chairs in an employee cafeteria can provide some rewards to the hard worker, if they have sufficient gluteus maximus. We know this now because we know Gil, and we’ve seen him bring that cushion to the lunchroom area.

Gil’s doctor prescribed that Gil get a gym membership and do certain workouts, with a particular focus on squats, so he could increase the muscle back there, but Gil didn’t have much to work with, and he knew his physical incongruence would prevent him from ever knowing the absolute joy of sitting in a chair, in a manner the rest of us take for granted.

***

“Have you ever had a bad back?” Imelda asked me at the gym. “It goes away, right? What if it didn’t? What if you experienced the worst back pain you’ve ever had, every day, for years? What would you do if you saw every expert, in every field you could think up, and they couldn’t help you? I am not a suicidal person, but I was in such horrible pain, for so long that I thought this was my life now. I just didn’t see how I could go on living like that.”

Imelda and I used to be great friends at our previous place of employment. When we switched jobs, our plan was to always keep in touch and keep connected in some way, but do we ever do that? No, we often leave those people behind. Sometimes, we don’t even remember who we left behind, until we randomly run into them, a decade later, at a gym.

The Imelda I knew back then was such a little thing, and she was someone I considered extremely attractive, because she hit all the bullet points of a small, attractive woman. The woman standing before me now had biceps, triceps, and her shoulders appeared so round and full. She almost looked like a different person, a big sister of the person I once knew. She was ripped, and I thought about all that in all of the complimentary and somewhat insulting ways. She lost all of her beautiful, feminine form, and replaced it with a form that suggested she was rugged and tough looking. She now looked like a person we probably shouldn’t mess with, and I meant that in complimentary and somewhat insulting ways.

“I was in a car accident, and it really wasn’t even a bad one,” she said. “The woman hit me just right, in a manner that happened to knock me out of alignment.” Imelda went onto to talk about all of the doctors, chiropractors, and massage therapists she visited over the years. “Every time you enter one of these offices, you have hope, and you pray that they are going to be the ones who are going to end it all for you. Then you leave their office, almost in tears, thinking that if you follow their orders it will end it once and for all. They tried, all of them tried, but nothing helped. I was so desperate, at one point, that I accidentally became an addict, addicted to pain meds, the worst of the worst ones,” she said. “They all provided some, limited relief, but the pain, the excruciating pain of not even being able to pick yourself up off the floor, was never far behind the temporary relief those drugs provided.

“When I finally met my Helen Keller, my miracle worker, I thought she was the worst of all. She was a physical therapist who said, ‘There is only so much I can do to help you, and you have to do the rest.’ She was so honest that I considered asking for my money back. What do you mean you can’t help me? What am I doing here, then? Her prescription was working out.

“Working out?” I said, “I can’t even get off the floor, and you’re telling me to workout?” It made no sense. I thought the massage therapist was an idiot who didn’t understand my level of pain, but I tried it. I did a couple of her low-stress workouts, and I had to admit I felt some relief, some relief as in a little. Then, I worked my way, through her slow, methodical, and prescribed progressions, until I felt even more relief. I told her about it on my next visit, and we cried together, because I thought she saved me, and she did, but it kept coming back. She suggested, after a time, and when she thought I was finally ready, a full-on powerlifting regimen, and I did it,” and here Imelda cried a little, right in front of me, “and she’s my savior now, and I tell her that, and thank her every time I see her.

“I might not be as attractive as I used to be,” she said, and I tried to dispel her of that notion, but she knew. “No, I know that I no longer look cute with all these muscles, but if you knew what I went through for those two long, excruciating years, you’d understand.”

After hearing Imelda’s testimonial, I thought of Gunther’s complaints about his incongruent calves. I thought about how biologists call the human body a marvel of engineering that is also structurally flawed in places, and in various cases. Some people might experience a flaw in their calves ability to respond to specific workouts, but those biologists also direct specific criticism at the structural flaws inherent in the back that make it prone to pain, injury, and dysfunction. Our rush to end our quadrupedal movement and achieve bipedalism is to blame, they say, and some suggest if we never want to have back pain again, we should revert back to the ways of our ancestors and crawl from space to space. Walking is what screwed us all up, because our rush to walk left little time for optimizing the spine’s ability to handle all of the new mechanical stresses bipedal movement caused. Our S-shaped spine enabled balance and flexibility, but it sacrificed some levels of stability when compared to the straighter spines of apes.

So, if Imelda’s testimony taught me nothing else, I learned to appreciate whatever temporary comfort I have, because this marvel of engineering we call our body has structural flaws that are vulnerable to tweaks, and there are no manufacturer’s warranties on these parts either. They’re as is. How was your back today? Good? So good that you didn’t even notice it? Notice it, mentally mark it down as a great day, and be grateful, because it is structurally flawed, and you might learn that one day, the hard way.

***

“You experienced a vasovagal syncope episode,” the doctor informed AJ Pinter.

“You experienced a vasovagal syncope episode,” the doctor informed AJ Pinter.

“A vaso what?” AJ asked.

“A vasovagal syncope episode,” the doctor added. “When you were listening to popular podcast, your vagus nerve became overstimulated, causing blood vessels to dilate and pool in the lower body, reducing flow to the brain. Such an episode can also trigger a sudden drop in heart rate and blood pressure, often due to a reflexive response to stress, pain, or fear.”

There are a number of results that can occur as a result of a vasovagal syncope episode, but in AJ’s experiences, it led him to faint. Most fainting spells are a reflexive response to a high level of stress, pain and fear. These episodes are usually brief, and recovery is quick, but those who study the effect suggest that the best way to experience such an episode, or recover from one, is to do so while lying down. This is impossible to do in most cases, as it’s almost impossible to predict when such episodes will occur.

AJ’s vasovagal syncope episode arrived when he was driving a delivery truck down the road. AJ had a documented history of fainting at the sight of blood, but that’s so common that documented research shows that 15% of the population faint at the sight of blood. What isn’t as common, and something an overwhelming majority of us have never heard of before, is that some hemophobia (the fear of blood) sufferers cannot maintain consciousness after hearing a discussion about blood. AJ’s case is so uncommon that some suggest that sufferers of those who lose consciousness as a result of hearing such a discussion could number under 1% of the population.

AJ’s vasovagal syncope episode arrived when he was driving a delivery truck down the road. AJ had a documented history of fainting at the sight of blood, but that’s so common that documented research shows that 15% of the population faint at the sight of blood. What isn’t as common, and something an overwhelming majority of us have never heard of before, is that some hemophobia (the fear of blood) sufferers cannot maintain consciousness after hearing a discussion about blood. AJ’s case is so uncommon that some suggest that sufferers of those who lose consciousness as a result of hearing such a discussion could number under 1% of the population.

AJ experienced just such an episode while listening to a popular podcast containing an in-depth discussion of blood. When AJ felt the symptoms coming on, he tried to pull off to the side of road, while simultaneously trying to turn the podcast off, but he couldn’t manage to do either in time. He lost consciousness while driving and hit an oncoming truck head-on. AJ broke bones in both hips in his pelvic region. If AJ is now able to endure the arduous, lengthy, and painful rehab his doctors prescribed for him, he’ll relearn how to walk but he may never be able to walk without a noticeable limp, and he’ll likely experience moderate to extreme pain for the rest of his life.

“And this happened because he heard a discussion about blood?” we asked the informant detailing for us the catastrophic consequences of AJ’s obscure condition. We asked that a couple times with an ‘Are you sure you have that right?’ tone, because we never heard of a person passing out as a result of hearing another talk about blood.

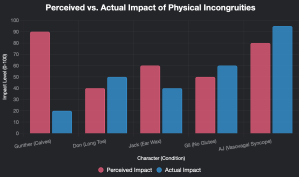

“AJ said it was an in-depth, detail-oriented discussion,” the man informed us, but that didn’t help us understand the matter any better. After working through the particulars of this discussion, we immediately thought about Gunther “the gym rat”, and how Gunther and AJ represented two ends of the spectrum of physical incongruities and their impact on personal happiness. Gunther chose to see an inadequacy that few would notice while failing to recognize the privilege of his otherwise healthy and fully-functional body. He chose to believe that it was “unfair” that he had such “puny calves”. AJ’s story, on the other hand, illustrates true unfairness: a random, obscure condition that upended his life in an instant. Gunther’s fixation is a choice to dwell on an issue most of us consider a non-issue, whereas AJ had no choice in the face of his medical condition. This contrast critiques Gunther’s lack of gratitude and perspective, suggesting that his pursuit of superficial congruence blinds him to the broader, more meaningful aspects of happiness—like the ability to walk, drive, or live without chronic pain. In that light, AJ’s tragedy illustrates the absurdity of Gunther’s self-imposed suffering, framing it as a cautionary tale about the dangers of obsessing over minor flaws at the expense of appreciating one’s overall well-being.

***

Some of us have knee-jerk, impulsive reactions to tales of the incongruent. “They’re weak!” some say. “How can a man survive, or thrive, if he cannot maintain consciousness during a discussion of blood?” Others react with sympathy and/or a sense of appreciation. Some might say that they’re put here, in our lives, to help us gain a renewed sense of appreciation for the idea of physical and mental congruence that we should cherish.

Some of us have knee-jerk, impulsive reactions to tales of the incongruent. “They’re weak!” some say. “How can a man survive, or thrive, if he cannot maintain consciousness during a discussion of blood?” Others react with sympathy and/or a sense of appreciation. Some might say that they’re put here, in our lives, to help us gain a renewed sense of appreciation for the idea of physical and mental congruence that we should cherish.

We rarely think about how our relative levels of congruence produces happiness, until we meet the incongruent. An enlarged heart, prostate, shrunken kidneys, or brain atrophy are more common incongruences that elicit sympathy, but how much sympathy do we have for a man with an elongated toe? If a man was dumb enough to complain about a lack of gluteal muscles, and he did so in manner that suggested he was upset about it, would we be able to restrain our laughter long enough to express sympathy?

“The man can’t sit in most chairs comfortably,” we say to scorn those who cannot control their impulses. “And he experiences chronic back pain as a result.” It’s funny, and it’s not, because most of us don’t consider sitting in a chair or walking on a sidewalk without discomfort one of the luxuries of life, until we have our perspective altered.

If we hear the terms congruent and incongruent, we often hear them in relation to social, psychological, physiological, philosophical, and spiritual concerns. We rarely talk about the physical, because it just feels so superficial. With all the problems in the world, both in general, and those we learn others experience, it almost feels narcissistic and trivial to complain about an apparent lack of buttocks, an elongated toe, or excessive wax build up. Yet, if we can’t walk or sit without some discomfort, it can affect our quality of life.

When we give thanks for all that we have, we often include good health, but we don’t really mean it. We say it, because that’s just something good people say. A part of us knows that good health can be fleeting, but it’s difficult to appreciate good health, or the incredible machine we have running life for us, until we hear others’ stories. We normally only appreciate such functions when we recover from deficiencies, pain, or some form of tragedy, but when we hear stories of poor health as a result of some odd physical incongruity, it renews our appreciation for even minor functions we currently have operating in peak form, because we know they’re not going to last forever.